Old Testament Life and Literature (1968)

Gerald A. Larue

Chapter 21 – Life and Literature of the Early Period

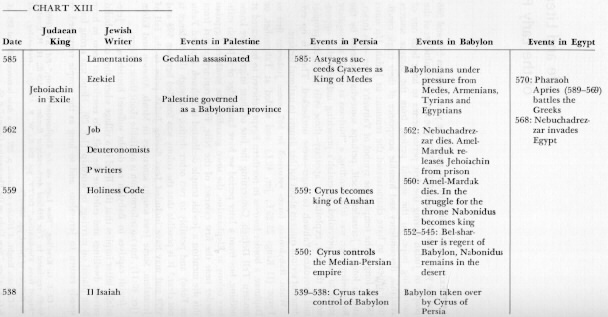

THE Exilic period falls into two parts: the years between 597 and 586 and the years after 586 up to 538 or 537. The mood and mind set of the people of Judah during the first period seems to have been one of continuing hope. In the second period, from the meagre sources available, despondency and humble acceptance of their tragic conditions appears to have characterized the remnant in Judah. Up until 586, so long as the temple-the symbol of Yahweh’s power-was intact, and so long as Jerusalem itself, perhaps somewhat battered by the Babylonian siege, was still standing, a "business as usual" atmosphere seems to have prevailed. Jeremiah’s preaching indicates that oppression of the poor, exploitation, apostasy-those evils which the prophet said provoked Yahweh to anger-were unchecked. There is no evidence of serious concern about further danger to national welfare.

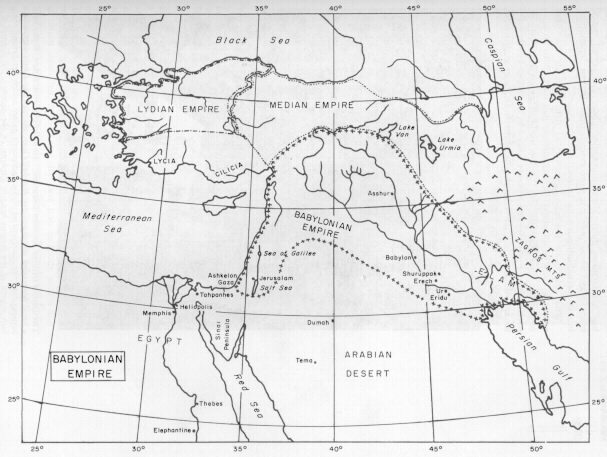

When Babylonian forces returned in 587, some Judaeans fled to Egypt (II Kings 25:25 f.; Jer. 42 f.) and settled at Tahpanhes, or Daphnae, a border fortress in northern Egypt believed to be located at modern Tell Defneh. Concerning the fate of these migrants we know nothing, but from a later period we have knowledge of a Jewish military colony at Elephantine, the town guarding the southern Egyptian border near the first cataract of the Nile. Fifth century papyri from this site mention a Jewish temple dedicated to Yahweh (spelled Yahu or Yaho) and possibly to two other deities, although the evidence is not clear.1 It is possible that the colony was founded between 598 and 5872 and may have included Jews fleeing Judah prior to the fall of Jerusalem. Some Jews sought sanctuary in Moab, Ammon and Edom (Jer. 40:11), but no information is available about these refugees.

Jewish captives in Babylon no doubt suffered hardships, but Jeremiah’s letter implies that they lived in a village where they could build private dwellings and cultivate the soil. No restrictions seem to have been placed on marriage or worship (Jer. 29). Hope was strong for a speedy return to Jerusalem, and so long as the temple remained, it must have been assumed that Yahweh had punished his people but had not forsaken them. More information about this period comes from Ezekiel whose prophetic work extends from the first deportation into the period following the destruction of Jerusalem.

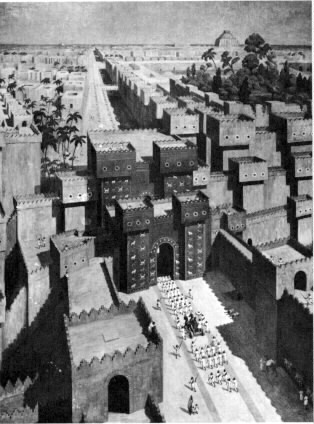

THE ISHTAR GATE OF ANCIENT BABYLON. An artist’s reconstruction, depicting a royal procession moving along Marduk’s way, through the Ishtar gate, and turning into the courtyard of Nebuchadrezzar’s palace which lies behind the lush growth of the famous hanging gardens. In the distance, the ziggurat of Marduk can be seen.

THE ISHTAR GATE OF ANCIENT BABYLON. An artist’s reconstruction, depicting a royal procession moving along Marduk’s way, through the Ishtar gate, and turning into the courtyard of Nebuchadrezzar’s palace which lies behind the lush growth of the famous hanging gardens. In the distance, the ziggurat of Marduk can be seen.

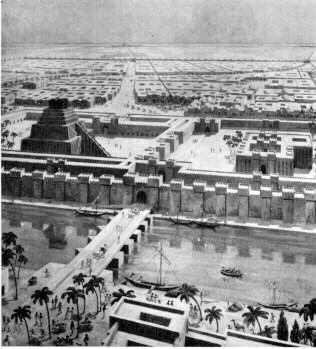

What impression the magnificent city of Babylon made upon the exiles can only be imagined. Nebuchadrezzar had made Babylon into one of the most beautiful cities in the world. This great metropolis straddled the Euphrates and was surrounded by a moat and huge walls 85 feet thick with massive reinforcing towers. Eight gates led into the city, the most important being the double gate of Ishtar with a blue facade adorned with alternating rows of yellow and white bulls and dragons. Through the Ishtar gate a broad, paved, processional street known as "Marduk’s Way" passed between high walls, past Nebuchadrezzar’s palace and the famous "hanging gardens" to the ziggurat of Marduk, the national god. This tremendous brick structure named E-temen-an-ki, "the House of the Foundation of Heaven and Earth," was 300 feet square at the base and rose in eight successive stages to a height of 300 feet. Temples dedicated to various gods and goddesses abounded. Beyond the city were lush orchards, groves and gardens, fed by an intricate canal system, from which supplies of fruits and vegetables were obtained. Domesticated animals, fish, wild fowl and game provided a varied diet. From east and west, north and south, came caravans with goods for trade and barter. In festal seasons, sacred statuary from shrines in nearby cities was brought to Babylon by boat and land vehicles. Truly Babylon was, as her residents believed, at the "center" of the world. The magnificent splendor of the city must have impressed the Jews, and as we shall see, there is some evidence that Babylonian religious concepts also made an impression on the exiles.

THE ZIGGURAT OF MARDUK IN ANCIENT BABYLON. An artist’s reconstruction of the ziggurat E-temen-an-ki with the shrine of Marduk before it. A bridge linked the two parts of Babylon which were separated by the Euphrates river. To lessen the pressure of the flow of the water the Piers of the bridge were boat shaped.

THE ZIGGURAT OF MARDUK IN ANCIENT BABYLON. An artist’s reconstruction of the ziggurat E-temen-an-ki with the shrine of Marduk before it. A bridge linked the two parts of Babylon which were separated by the Euphrates river. To lessen the pressure of the flow of the water the Piers of the bridge were boat shaped.

Some Judaeans were held as hostages within the city proper and among these were Jehoiachin, the exiled king, and his family. Tablets discovered in the excavation of the city and dated between 595 and 570 include lists of rations paid in oil and barley from the royal storehouses to captives and skilled artisans from Egypt, Ashkelon, Phoenicia, Syria, Asia Minor and Iran. Specifically mentioned were "Yaukin, king of the land of Yahud" (Jehoiachin of Judah), his five sons, and eight other Judaeans. It is important to note that Jehoiachin was still called "King of Judah." Royal estates in Judah were managed, at least up until 586, by "Eliakim, steward of Jehoiachin," whose seal impressions have been found in excavations at Debir and Beth Shemesh.

The immediate impact of the news of the fall of Jerusalem upon the exiles must have produced shock and horror. But, as we shall see from the literature, there developed a new hope for restoration, a new discovery of the meaning of election and covenant, and a new sense of destiny, which grew in strength and excitement until something of a triumphant climax is reached in the writings of Deutero-Isaiah. Not all exiles responded to the new concepts and some of Isaiah’s words castigate these blind, unresponsive ones, but as it is impossible today to read, unmoved, the stirring, inspiring words preserved from those times, it is quite reasonable to imagine that there must have been those roused to peaks of hope and encouragement as they contemplated the future.

EZEKIEL

Among the elite of Judaean society deported by Nebuchadrezzar in 597 was Ezekiel, a son in the priestly family of Buzi (1:3). The Jews were settled on the Kabari canal, or the "river Chebar" as it is called in Ezek. 1:1, which tapped the Euphrates’ waters for agricultural and navigational purposes. The initial verses of the Book of Ezekiel, written in autobiographical form, speak of the thirtieth year, but no guidance is given as to the significance of this period which could refer to the thirtieth year of the prophet’s life, to the time when the oracles were recorded some thirty years after his first vision, or to the thirtieth year of the Exile. The vocational summons which came in the fifth year of Jehoiachin has been dated July 21, 592.3

Innumerable problems are associated with the Book of Ezekiel. The prophet stipulates that he is among the exiles, but his words in Chapters 1 to 24 are addressed to Jews in Jerusalem. May one assume that he was permitted to break his exile and return to Jerusalem-and there is no evidence that this was possible-or did he send his oracles back to the Jerusalemites by courier? For some, his intimate knowledge of events in Jerusalem suggests that he was in that city, for his words had devastating effects upon some hearers there (cf. II: 13-14). Consequently, it has been proposed that Ezekiel prophesied in Palestine and that the Babylonian setting is the result of editing; or that he was exiled to Babylon, received his call there, and then returned to Palestine; or that he spoke in Babylon for the benefit of his hearers there, having received detailed information about events in Palestine by courier or by clairvoyance.4 No clear solution is possible and scholars are divided between a Babylonian and a Palestinian provenance. We will assume that Ezekiel remained in Babylon and that references to his visits to Jerusalem are visionary experiences, perhaps supplemented by his personal memories of the city and by news received from informants from Palestine.

The integrity of the book has been challenged, with one scholar limiting authentic Ezekiel passages to some 170 verses,5 and others accepting almost the whole book as genuine6 or attempting to identify larger sections containing an Ezekiel core.7 The book has been classified as a third century, pseudonymous story about a priest in the time of Manasseh, which was later edited to provide the Babylonian setting-in which case there would have been no such person as Ezekiel.8 It has also been dated in the time of Manasseh and identified as a northern Israelite work, later edited by someone from Judah and given a Babylonian setting.9 Most scholars accept a sixth century date but recognize that the book was carefully edited, perhaps by the prophet’s disciples, so that it is, therefore, very difficult to isolate genuine Ezekiel materials.10 Because of the complexity of this problem, we shall make no attempt to identify genuine Ezekiel passages. The book will be accepted as "Ezekielan" (Ezekiel and his disciples) except where study of the text has made it clear to most scholars that we are dealing with non-Ezekiel intrusions.

The book is usually divided into four major parts:

I. Chapter 1-24 Prophecies against Jerusalem and Judah delivered prior to 587.

1:1-3:27 The prophet’s call and commissioning.

4:1-7:27 Oracles of judgment.

8-11 Visions of the temple.

12 Dramatizations of destruction and exile.

13-19 Oracles against Jerusalem.

20-24 Oracles of judgment.

II. Chapters 25-32 Oracles against foreign nations.

25 Against Ammon, Moab, Edom and Philistia-often labeled post-Ezekiel.

26-28 Against Tyre and Sidon.

29-32 Against Egypt.

III. Chapters 33-39 Oracles of restoration.

33-36 Oracles of promise.

37 Oracle of the dry bones.

38-39 Oracles of Gog and Magog.

IV. Chapters 40-48 Visions of the new temple and the new Jerusalem.

40-42 Details of the temple.

43:1-12 The return of the glory of Yahweh.

43:13-46:24 Temple ritual.

47 Sacred waters for healing.

48 Tribal allotments.

EZEKIEL’S CALL

Read Chs. 1-3

Yahweh’s summons to Ezekiel came as a vision which combines imagery much like that used by Isaiah of Jerusalem (Isa. 6) with an inner conviction not unlike that of Jeremiah (Jer. 1:5) of being chosen or destined for the prophetic role. The theophany out of the north11 is usually associated with an approaching storm transmogrified in Ezekiel’s mind into the chariot of Yahweh.12 The imagery, which strikes the modern mind as strange and weird,13 may have developed out of the prophet’s recollections of the enthronement of Yahweh in the Judaean New Year ritual,14 with some influence coming from the Babylonian setting.15 The concept of the deity enthroned upon the cherubim16 calls to mind the sacred ark and is in keeping with the use of winged figures, often animals with human faces, as symbolic guardians at the entrances to buildings or on throne chairs.17

Like other prophets, Ezekiel was commissioned to bring unpleasant information and announce the forthcoming annihilation of Jerusalem. The description of the prophet eating a scroll (2:8-3:3), symbolizing the absorption of the message (cf. Jer. 15:16), interrupts the commissioning narrative which, as many scholars have pointed out, should include a statement of the reception Ezekiel might expect from his countrymen. As Yahweh’s watchman, the prophetic responsibility included the burdensome knowledge that with him rested the safety and salvation of those to whom he was sent.

ORACLES OF JUDGMENT

Read Chs. 4-7

In five dramatic acts, the prophet depicted the siege and destruction of Jerusalem and prolonged punishment for Israel and Judah. It should be remembered that symbolic acts depicted reality, and what the prophet did was as good as accomplished, so to speak, as an act of Yahweh, even though the event had not yet taken place. Jerusalem would fall by siege and sword, and famine and pestilence would take their toll. Those who escaped death would testify that Yahweh had indeed kept his promise of destruction (6:10). Here we find no nationalistic idealization of the city and the temple like that characterizing Isaiah’s work. Ezekiel saw no hope for the city or the temple: both would perish.

Nor did Ezekiel envision a brief period of punishment: the Exile would fall by siege and sword, and famine and pestilence would take reading in the LXX, the prophet lay on his left side portraying the period of Israel’s punishment, and he lay for forty days on his right side to portray Judaean punishment. Subtracting 190 years (days), the LXX reading, from 721, the date of the fall of Israel, would give a date of 531 for the time of the termination of that punishment. The forty years (days) of Judah might be symbolic, signifying one generation or simply a long time. Using 586, the date of the fall of Jerusalem, and subtracting the forty years (days) the Exile should have ended in 546, a date reasonably close to the historical termination.

Read Chs. 8-11

Perhaps Ezekiel’s background as a member of a priest’s family heightened his sensitivity to the separation of the holy and the profane. For the prophet the profanation of the religion, the temple and the land was the underlying cause of that which had happened and was about to happen. He envisioned the idolatry practiced in the temple precincts in Jerusalem, the destruction of the wicked and the departure of the glory ( kabod) of Yahweh. The opening vision, dated September 7, 591, reports the miraculous transportation of the prophet to Jerusalem where he witnessed cultic rites of the god Tammuz,18 sun worship and the adoration of idols. Such apostasy was more than Yahweh’s holiness could tolerate, and Ezekiel watched the withdrawal of Yahweh’s glory ( kabod). Without the divine presence, Jerusalem had no strength and could not stand. It was clear that those presently exiled in Babylon had been given sanctuary from the final holocaust and that any hope for the future rested with them.

AN ALTAR FROM MEGIDDO. A horned Canaanite incense altar just over two and a half feet high was found at Megiddo. Such altars were used by the Judaeans and were symbols of apostasy to Ezekiel who predicted their destruction (Ezk. 6:4, 6) and to Jeremiah who said that there were as many incense altars in Jerusalem as there were streets (Jer. 11:13).

AN ALTAR FROM MEGIDDO. A horned Canaanite incense altar just over two and a half feet high was found at Megiddo. Such altars were used by the Judaeans and were symbols of apostasy to Ezekiel who predicted their destruction (Ezk. 6:4, 6) and to Jeremiah who said that there were as many incense altars in Jerusalem as there were streets (Jer. 11:13).

Read Ch. 12

Having been brought back to Babylon, the prophet dramatized the Exile to assure the skeptics that Jerusalem’s end was at hand. The surviving remnant would testify to the evil that brought about the downfall and to the fact that Yahweh, rather than being defeated by another god, had, in his anger, willed the destruction of his own people.

Read Chs. 13-19

There were those who would not accept the harsh realities of Ezekiel’s teaching and who refused to believe that Jerusalem would fall or that the Exile would be prolonged. Jeremiah had faced these same attitudes and had been compelled to write a letter to prepare the exiles for a long absence from Judah. So Ezekiel, in uttering oracles on the fall of Jerusalem, included a scornful denunciation of false prophets whose utterances were words of their own composing, expressions given in the futile hope that somehow Yahweh would bring them to fruition. The true prophet spoke Yahweh’s words, and Yahweh’s words were of doom.

So great was Jerusalem’s evil that, on the basis of corporate personality, the combined weight of the righteousness of Noah, Daniel and Job, if they were present, could not save the people. Noah is, of course, the survivor of the flood; Daniel may be the hero of the Canaanite myths of Aqht or an unknown prototype of the hero of the biblical book of Daniel; and Job was a righteous sufferer whose story became the basis for the book of job. This evaluation of Jerusalem’s ills may have been added in the post-Exilic period.

The prophet reiterated Israel’s history in Chapter 16, recalling Yahweh’s protective care of the unwanted offspring of mixed parentage; the covenant bond described in marriage terms; and the harlotry of the nation by which Yahweh was betrayed. Judah’s evil was greater than that of Sodom and Gomorrah. Punishment had to follow. Ezekiel did not rest his prophecy in a negative future. He peered beyond and saw forgiveness, restoration and the formulation of an everlasting covenant.

The eagle allegory in Chapter 17 may be an expansion of Ezekiel’s rejection of Egypt as a protective haven for fleeing Judaeans. The exposition of the principle of individual responsibility in Chapter 18 may not be by Ezekiel.19 The problem of theodicy, which assumed great importance in the Exilic period, is met by the argument that the wicked perish and the righteous survive; each man suffers for his own sins. If one who was righteous throughout his life should perish, perhaps it could be concluded that a sudden reversal of behavior patterns had condemned him. In the same manner, the sparing of an evil man could be explained by a last minute repentance. The idea of corporate personality is utterly rejected: suffering could not be explained by reference to another’s sin; each man paid his own penalty.

Read Chs. 20-24

In another recital of the nation’s apostasy there is no idealization of the desert wanderings as in the writings of the eighth century prophets. Yahweh’s ordinances were violated from the beginning. After each violation Yahweh hoped for repentance and change in the next stage of Israel’s pilgrimage, and each time the hope proved vain. Once again, hope was projected into the future, when dispersed peoples would return, purged of their rebellious elements.

Oracle after oracle hammered home the prediction of the fall of Jerusalem; the oracles on Yahweh’s sword which did not distinguish between the righteous and the wicked, on Jerusalem’s blood-guilt (21), on the burning away of the dross (22:17-22), on Samaria and Jerusalem, on the unfaithful wives of Yahweh (23), on the boiling pot (24:1-14), and finally on the death of Ezekiel’s wife (24:15-24). The section closes with word of the fall of Jerusalem (24:25-27).

Read Chs. 25-32

Pronouncements against foreign nations follow. It is very difficult to determine which words actually belong to Ezekiel. Chapter 25 condemning Ammon, Edom and the Philistines is often labeled non-Ezekiel.20 just as Psalm 137 recalls the delight of the Edomites at Jerusalem’s fall, so Ezekiel 25 recalls the glee of Judah’s neighbors.21 Oracles against Tyre and Sidon are suspect (26-28), but could be expansions of Ezekiel’s sayings. Tyre yielded to Nebuchadrezzar about 572 after a thirteen-year siege. The obscure allusion to the king of Tyre in the garden of Eden reflects a tradition similar to that preserved in J.

In the first of two anti-Egyptian oracles (29:1-16, 17-21) the image of Egypt as a great dragon recalls a mythological pattern, lost to us, in which Yahweh battled the dragon of the deep.22 Egypt, Ezekiel believed, would be destroyed by Nebuchadrezzar (30:10 ff.). The section closes with a dirge on the descent of Egypt to the netherworld.

Read Chs. 33-39

For Ezekiel the exile was an interim stage between the destruction of the old Israel and birth of the new. Chapter 33, a transition chapter, leads to oracles promising rebirth and restoration. In 33:1-9, which is linked to 3:16 ff., the prophet is depicted as a watchman, and 33:10-20, which is linked to Chapter 18, discusses individual responsibility. The announcement that Jerusalem had fallen (33:21 f.) was followed by a denunciation of rulers or shepherds of Jerusalem (34:1-10) whose mistreatment of the flock they were supposed to lead is contrasted with the role of Yahweh, the master shepherd or, perhaps, the "good" shepherd (34:11 ff.).

Oracles of judgment against foreign nations and promises for the future of Judah precede the vision of dry bones (37:1-14). The exiled people were the dry bones, without hope and convinced that they were dead now that the city of Jerusalem had been destroyed (37:11). But the Exile was not to be the end. By Yahweh’s command, the miracle of renewal begins and bones are activated; new life is breathed into them and the vision of a new future in their own land is given. That future included the rebirth of the united kingdom of Israel and Judah under a Davidic monarch, a new sanctuary and an eternal covenant. The new ideal which plays so large a part in Ezekiel’s subsequent oracles begins to take form. The temple and old city were gone. Ezekiel looked to the new city and the new temple. The Davidic line was still alive in the family of Jehoiachin, and in it Ezekiel saw the leadership of the future. The old covenant had been violated (perhaps terminated) and Ezekiel envisioned new relationships bound by a covenant that could never fail.

Oracles on Gog and Magog picture a climactic battle against Israel. The foe cannot be identified with certainty. Gog may refer to King Gyges of Lydia in Asia Minor who was known as Gugu from Akkadian records, to a Babylonian deity Gaga, to an Armenian people called Gaga, or to some mythological foe. Magog has been said to represent the Scythians. Meshach may refer to Mushku or classical Phrygia in Asia Minor. Tabal may be Tabal of Urartu in the Lake Van area. Gomer may be the Cimmerians.23 All identifications are tentative. These enemies are symbols of people in power as the prophet writes. Their failure to overcome restored Israel will enable Yahweh to demonstrate his power and holiness. Whether this battle was meant to symbolize the close of a time of tribulation and the inauguration of a new era of peace and prosperity is not clear, but it does serve to provide the setting for the introduction of the vision of the new temple and the new Jerusalem.

THE NEW JERUSALEM

Details of the temple appearing in Chapters 40 to 42 do not parallel in every detail the description of Solomon’s temple in II Kings 6 f. The temple stood at the center of the new theocratic state. Ministrants were to be Levitical priests of Zadokite lineage. Now Yahweh’s glory ( kabod) returned (43:1-5), symbolizing the restoration of covenant relationships. The picture is idyllic, and paradisiac aspects are emphasized by references to sacred trees and waters reminiscent of the J story of Eden. Springing from beneath the temple was a river with purifying waters so potent that the saline Great (Dead) Sea could be made to sustain marine life and give nourishment to trees whose fruits would never fail and whose leaves would heal (47:1-12). The book closes with the division of land among the tribes and the announcement of a new name for Jerusalem: "Yahweh-shammah," meaning "Yahweh is there."

CENTRAL THEMES

- Perhaps the stress on the importance of the cult reflects Ezekiel’s priestly background. The harshest condemnations are directed against apostasy and acts which profaned the temple. In the idealized future state, a purified people observe the rules for holiness, and sacrifices are made in the correct manner. Ritual and moral laws are viewed as divine gifts enabling man to know how to live (20:11 ff.), and the uniqueness of Yahweh’s people is to be expressed through the cult and the law.

- As one commissioned to preach judgment of the past and present, Ezekiel saw himself as a watchman responsible for the safety of the exiles. By keeping before the people the basis for punishment and by exposing the spirit of lawlessness that had characterized their relationships to Yahweh from the bondage in Egypt to the Exile in Babylon, the prophet hoped to warn them away from any continuation of this attitude. Like II Isaiah Ezekiel found his listeners unwilling to take his teachings seriously.

- A definite change in emphasis can be discerned in Ezekiel’s teachings. Up until the fall of Jerusalem in 586, his message was of doom. After the destruction of the temple and the city, he stressed the holy community, the ideal nation and the glorious future that was part of Yahweh’s plan. It was in the future state that the election formula would find complete fulfillment: "You shall be my people, I will be your God" (cf. 11:20; 14:11; 36:28; 37:23, 27).

- The Exile was an interim stage, between the termination of old relationships and the beginning of new associations. In one sense the new age would be a restoration of the old, with a new Exodus and a new everlasting covenant, with the kingdom restored under the Davidic kingship.

- The use of the concept of the divine kabod, which is, in essence, identical to Yahweh,24 enabled the prophet to depict the deity without employing gross anthropomorphisms and, simultaneously, to move away from the idea that Yahweh’s name ( shem) rather than the real presence was in the temple.25

- The concept of individual responsibility, if it is really Ezekiel’s, is not new for it is implicit in J, in Abraham’s query when the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah was under discussion: "Will you really destroy the righteous with the wicked?" (Gen. 18:23), and in David’s confession of responsibility for evil (II Sam. 24:17). It is also stated as a law in Deut. 24:16. Pragmatically, it was obviously untenable, for there were those who had escaped death despite the fact that they were more evil than some who had died. These were spared, it was argued, as examples of the wickedness of the Jerusalemites (12:16), to demonstrate the justice of the complete destruction of the city (14:21-23).

On the other hand, the concept has another significance. It marks the cancellation of old debts. What happened to those who escaped did not depend upon what their ancestors had done, but upon what each individual did. The nation with its corporate identity had perished, the individual Jew remained. Participation in the new tomorrow rested upon individual response to Yahweh’s promises. - Restoration would come, not because the people deserved it, but because Yahweh’s reputation had been besmirched (36:22). The restoration of the people, the punishment of mocking neighbors and the crushing of the great powers would demonstrate that Yahweh had not been defeated, but had acted deliberately against his people. Restoration of Israel vindicated Yahweh.

LAMENTATIONS

The effect on Jewish morale of the downfall of the capital city and the destruction of the temple which had symbolized Yahweh’s enduring patience and love for nearly 400 years must have been devastating. Only a small collection of five poems, written over a considerable period of time, provides any insight into the shock, horror and grief of the people.

Ancient tradition assigns the authorship of Lamentations to Jeremiah. A prefatory comment in the LXX says the poems are by Jeremiah, possibly on the basis of II Chron. 35:25,26 but modern scholars reject this hypothesis for several reasons. There is no indication in the Hebrew version that Jeremiah was the author, and ideas presented within the poems contradict Jeremiah’s teachings. For example, it is highly unlikely that Jeremiah, out of his personal experiences of Yahweh, would state that prophets did not receive visions (Lam. 2:9); nor would the prophet accept the argument that the sins of the past were responsible for the destruction (Lam. 5:7), for he consistently preached that the apostasy of the day would engender divine wrath. The plaintive reminiscence of the hope for deliverance by Egypt (Lam. 4:17) contradicts Jeremiah’s dismissal of the possibility of aid from the south. The authors or author remain unknown.

Four poems (chs. 1-4) employ an artificial alphabetical acrostic structure in which a sequence of the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet is followed in the opening word of each stanza.27 The fifth imitates the structure using twenty-two lines without the alphabetical scheme. The first three chapters, with minor exceptions, employ three lines to each stanza;28 the fourth poem has two lines and the fifth has one per stanza.29 Despite formal structuring, the poems convey genuine pathos and deep emotional stress. It has been suggested that the alphabetic form was designed for mnemonic reasons, or perhaps, to indicate that the author’s feelings and suffering ran the emotional gamut from aleph to tau, or in present-day speech, "from A to Z." Attempts have been made to discover some chronological sequence for the poems on the basis of content. Chapters 2 and 4, often attributed to a single writer, are sometimes considered to be earliest because they appear to be very close to the actual time of the fall of Jerusalem. Some scholars date Chapter 1 to the post-Exilic period when the temple was rebuilt;30 others label it the earliest of the poems.31 A more likely suggestion is that all of the poems reflect the Exilic period and, despite their independence and individuality, may reflect the work of one author (or perhaps two) writing over a considerable period of time.32

Read Ch. 1

The opening word of the collection, "how" (Heb. ‘ekah), gives the Hebrew title to the book33 and introduces the dirge form of the poem.34 The desolate city is portrayed as a widow, not dead but alone, forsaken, weeping in the night when none can see. The contrast between the glories of the past introduced in the first verse and the present state portrayed in subsequent verses conveys to the reader the desolation of the city. There is a forthright recognition that Jerusalem’s sin caused the downfall, and the imagery of the adulterous woman (1:8-9) is reminiscent of Hosea.

The dirge terminates in Verse 11, and an individual lament, written in the first person singular, portrays the city speaking and explaining the tragedy that occurred. Verse 17 returns to the third person singular form and describes Yahweh as the commander of Jerusalem’s enemies. The closing verses, a confession of guilt written in the first person singular, portray the unfaithful wife in the days of distress calling for help to her lovers (other gods?) to no avail. The poem closes with an expression of grief and anguish. Because there is a suggestion in the poem that Jerusalem was not completely destroyed, it is possible that these verses were written after 597 but before the collapse of the nation in 586.

Read Ch. 2

The first ten verses of Chapter 2 describe Yahweh as the enemy, bending his divine bow against his own people, pouring out anger without restraint, scorning the sacred temple and altar and satisfied only when the city lay in ruins. For the stunned, shocked elders and maidens sitting in silence in sackcloth and dust, the event is simply incomprehensible. The people are dazed, bewildered and numbed by the horror of the event.

In his own words, as a witness, the writer takes up the description (vss. 11-22). Children die of starvation in their mothers’ arms. Cannibalism is practiced. The dead lie in the streets. Nothing remains but a broken people in a ruined city through whose smouldering ruins rings the mocking laughter and remarks of enemies and tormentors. Yahweh fulfilled his threats of punishment (2:17) despite the false omens of hope given by some prophets. But the real cry of anguish to Yahweh is in the partially expressed question "Oh Yahweh, how could you act without pity or mercy?"-a cry of theodicy stemming from the writer’s emotional response to the death of loved ones (2:22) and the terrible results of the siege.

Read Ch. 3

The first thirty-nine verses of the third poem are in the form of an individual lament in which the nation is the speaker,35 personified as a man who has experienced Yahweh’s anger. Some of the imagery suggests that the poet had Jeremiah in mind as he described the city’s misadventures. The city experienced divine wrath, was stoned and broken, encircled without hope of escape, torn to pieces, pierced by arrows and ultimately become the laughingstock of enemies. In Verse 21 the mood of the poem changes and the writer affirms the constant loyalty of Yahweh.

Verses 40-47 are part of a national lament written in the first person plural and they call for a return to Yahweh even as they confess that sins had not yet been forgiven (vs. 42). The closing verses (48-66) return to the first person singular and express the sufferer’s complaints, words of assurance (55 ff.) and a prayer against enemies (61 ff.).

Read Ch. 4

The fourth poem, which has affinities with the second, begins as a lament in the third person singular, shifts in verses 17 to 20 to the first person plural and ends with a statement of hope for the exiles and a promise of punishment for Edom. The immediacy of the horrors described suggest that the poem was written shortly after the siege, but there is a reflective note that implies that the event is past and the poet is thinking back on what took place. The writer recalls the scattered stones of the temple, the leading citizens transformed into living scarecrows, children crying for food and, once again, cannibalism. The people looked in vain for help from Egypt (4:17) and, when the city fell, there were none who escaped (4:19). The closing words express the belief that the time of punishment is over and the Exile ended (4:22).

The last poem is a national lament setting the predicament of the people before Yahweh, calling the deity to witness what the nation had become. There is no admission of guilt, only the argument that the fathers (perhaps the leaders) had sinned and the punishment fell upon those who suffered the onslaughts of the Babylonians. Even the cry "we have sinned" (5:16) may reflect the totality of the group through time, and point back to the nation through history rather than signify a recognition of responsibility by the present sufferers. The social evils of war are depicted throughout the poem, and the miserable plight of the exiles is revealed. The poem closes with a statement of. praise of Yahweh and a questioning cry reminding Yahweh of the people’s need and seeking restoration of relationships.

THEODICY

In depicting the horrors of the fall of Jerusalem, the poems raise the problem of theodicy. There is an acknowledgment of sin, but there is also the recurring note of incredulity that Yahweh could have brought such horrendous punishment upon his own people. There is the recognition that an angry Yahweh was himself the enemy and that both good and evil come from Yahweh (3:38), but there is also a note of impatience arising out of the conviction that the punishment had taken place, Yahweh had demonstrated his just anger, so how long must punishment continue? The final request asks that Yahweh assert himself on behalf of his people.

CULTIC USE

After the temple was destroyed again in A.D. 70 by the forces of the Roman general, Titus, the book of Lamentations was liturgically used on the ninth day of the Jewish month Ab (July-August) to commemorate both the Roman and Babylonian destructions. How far back the liturgical use of Lamentations can be traced is debatable, but Zechariah 8:18-19 suggests fasts associated with the siege and destruction of Jerusalem (cf. II Kings 25:1-4; Jer. 39:2) and Zechariah 7:3 ff. implies a long practice of the custom, dating back to the Exile. A Sumerian poem of similar nature, bewailing the fate of the city of Ur,36 written during the early part of the second millennium bears striking affinities to the Hebrew poem.37 It is possible that the Sumerian poem was used in a commemorative ritual, so that the Jewish poet may have composed his laments according to a custom well established and well known in the Near East. It is reasonable to suggest that the poems of Lamentations were employed in a commemorative liturgy during the Exile, with the first person singular portions recited by a leader representing the corporate group or the city and other portions spoken by the congregation.

Endnotes

- Cf. E. G. Kraeling, "New Light on the Elephantine Colony," BA, XV (1952), 50-67; reprinted in The Biblical Archaeologist Reader, pp. 128 ff.; H. H. RowIey, "Papyri from Elephantine," DOTT, pp. 256 ff.; W. F. Albright, Archaeology and the Religion of Israel, pp. 168-175.

- Cf. John Bright, A History of Israel, p. 327. For a date between 569 and 525, cf. E. G. Kraeling, "New Light on the EIephantine Colony," p. 65.

- H. G. May, "Ezekiel," The Interpreter’s Bible, VI, 68, discusses the dating problems arising out of autumnal and vernal calendars. All dates in this section follow May’s chronology.

- For a discussion of the history of the debate over locale, cf. Eissfeldt, op. cit., pp. 367 ff., and May, Interpreter’s Bible, VI, 51 f.

- G. Hölscher, Hesekiel der Dichter und das Buch (Giessen: A. Töpelmann, 1924).

- C. G. Howie, The Date and Composition of Ezekiel, Journal of Biblical Literature Monograph Series, IV (Philadelphia: Society of Biblical Literature, 1950).

- H. G. May, Interpreter’s Bible, VI, 50, lists the following passages believed to incorporate genuine Ezekiel material which cannot be isolated: 5:5-17; 7:1-27; 10:1-22; 12:21-28; 13:1-23; 17:11-21; 20:45-49; 21:1-7; 22:1-31; 23:31-35; 24:6-24; 26:1-6; 27:9b-25a; 27; 28:1-10; 29:1-5; 30:1-26; 31:10-18; 32:17-32; 33:30-33; 37:1-14; 42:13,14; 43:6-12, 18-27; 44:1-2, 6-31; 45:10-25.

- C. C. Torrey, Pseudo-Ezekiel and the Original Prophecy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1930).

- James Smith, The Book of the Prophet Ezekiel (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1931).

- For a discussion of the textual history, cf. Eissfeldt, op. cit., pp. 372 ff., Weiser, op. cit., pp. 224 ff.

- In Canaanite mythology, the pantheon was located in the north and this concept entered Hebrew-Jewish thought. Cf. Ps. 48:2 where Yahweh’s abode on Mount Zion is located in the far north.

- Cf. Ps. 6:48; 104:3, where Yahweh is said to ride the clouds as a chariot. Ba’al also rode the clouds, cf. Gaster, Thespis, pp. 89, 122, and passages cited there.

- This imagery prompted an attempt at a Freudian analysis of Ezekiel, cf. E. C. Broome, "Ezekiel’s Abnormal Personality," Journal of Biblical Literature, LXV (1946), 277-292. For a refutation see C. G. Howie, op. cit., pp. 69 ff.

- Cf. May, The Interpreter’s Bible, VI, 69 for a brief statement and bibliography.

- Cf. Oesterley and Robinson, op. cit., P. 274.

- The four living creatures are identified as cherubim in Ezek. 11:22.

- Cf. the mythological cherubim in the J story of the garden of Eden (Gen. 3:24).

- Tammuz was a Sumerian deity. According to the Epic of Gilgamesh, he was one of the lovers of Ishtar, the fertility goddess. Wailing rites were associated with her rejection of him, or perhaps with Tammuz’ role in the nature cycle.

- May, Interpreter’s Bible, VI, 49.

- Cf. May, op. cit., pp. 200 ff. for details.

- See also Lam. 4:21.

- Cf. Isaiah 27: 1; 51:9-10; Job 38:8-1 1.

- Cf. Saggs, op. cit., pp. 116 f., 223.

- Cf. Jacob, Theology of the Old Testament, p. 81.

- Cf. Vriezen, An Outline of Old Testament Theology, P. 247.

- The third century preface reads: "And it came to pass, after Israel was taken captive and Jerusalem made desolate that Jeremiah sat weeping and lamented with this lamentation, saying . . ."

- Poems (chapters) 2, 3, 4 make slight variations, placing the seventeenth letter (pe) before the sixteenth letter (‘ayin).

- 1:7 and 2:19 have four lines each.

- The poetic structure is clearly depicted in the translation by N. K. Gottwald in Studies in the Book of Lamentations, Studies in Biblical Theology, 14 (London: S.C.M. Press, 1954), pp. 7-18; or the translation of T. J. Meek in The Complete Bible, An American Translation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1939).

- R. H. Pfeiffer, Introduction to the Old Testament, P. 723.

- Weiser, op. cit., p. 306, citing Rudolph.

- N. K. Gottwald, "Lamentations," The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible.

- The title "Lamentations" is from the Vulgate translation of the LXX "Threni."

- Cf. the dirges in II Sam. 1:19; Jer. 9:16 ff., noting the use of the word "how."

- Cf. Gottwald, Studies in the Book of Lamentations, pp. 37-41. For an opposing point of view, cf. T. J. Meek, "Lamentations," The Interpreter’s Bible, VI, 23.

- Cf. ANET, pp. 455-463 for the translation by S. N. Kramer.

- For similarities and differences and an excellent discussion of the significance of this kind of writing, see T. H. Gaster, Festivals of the Jewish Year (N.Y.: William Sloane Associates, 1953), pp. 200 ff.

Old Testament Life and Literature is copyright © 1968, 1997 by Gerald A. Larue. All rights reserved.

The electronic version is copyright © 1997 by Internet Infidels with the written permission of Gerald A. Larue.