Old Testament Life and Literature (1968)

Gerald A. Larue

Chapter 20 – From the Fall of Nineveh to the Fall of Judah

FOR three years Ashurbanipal’s successor held the Assyrian throne and at his death Sin-shar-ishkin became king. In the summer of 612, Nabopolassar, a Chaldean leader, aided by Medes and northern nomads, attacked, looted and destroyed Nineveh, an event that marked the crumbling of the last vestiges of power in Assyria and established the foundations for the Neo-Babylonian Empire. There is some evidence that the defeat of Nineveh was the occasion of rejoicing in Judah, although the Assyrians established a new capital at Harran. Within a few years Harran was conquered by the Medes.

NAHUM

The reaction of at least one individual to the fall of Nineveh is preserved in a poem echoing sheer mocking joy in the defeat of Assyria. The book of the prophet Nahum falls into two parts: Chapter 1 contains an incomplete poem in an alphabetic acrostic form,1 and Chapters 2 and 3 are concerned with Nineveh. Attempts have been made to read out of this short poem something of the writer’s status and personality, but there is really no way of learning much about the man for, in his jubilant mood, he treats only one theme-Nineveh. His words form a triumphant shout of praise to Yahweh that the enemy has fallen. His native village of Elkosh (1:1) has not been located.2 The prophet may have been a Judaean who reacted with intense pleasure at the news of Nineveh’s defeat or he may have been a descendant of the exiles of Israel living in a village near enough to Nineveh to enable him to witness the siege, thus accounting for the graphic descriptions in his poem. He may have been a cult prophet in Jerusalem.

The two chapters dealing with the siege (chs. 2-3) appear to have been written near the time of the battle. The reference to the sack of Thebes (3:8) guarantees a date after 663, the date of Ashurbanipal’s successful attack. The context of the poem suggests a date close to 612.

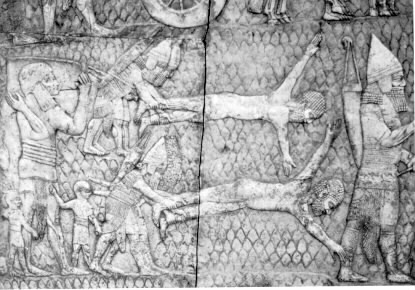

ASSYRIAN SOLDIERS FLAYING CAPTIVES. Nahum’s bitter attitude toward the Assyrians may have been engendered in part by the knowledge of the cruel treatment given to prisoners and conquered peoples by Assyrian warriors. The portrayal is from one of the wall panels of Sennacherib’s palace at Nineveh (early seventh century).

ASSYRIAN SOLDIERS FLAYING CAPTIVES. Nahum’s bitter attitude toward the Assyrians may have been engendered in part by the knowledge of the cruel treatment given to prisoners and conquered peoples by Assyrian warriors. The portrayal is from one of the wall panels of Sennacherib’s palace at Nineveh (early seventh century).

The opening chapter is a separate work which employs theophanic imagery (1:3b-5) and depicts Yahweh as an avenger (1:2-3, 9-11), a wrathful deity (1:6), a refuge for his people (1:7-8), and a deliverer (1:12-13). While it cannot be determined for certain, it seems that someone other than Nahum wrote this chapter. The liturgical or hymnic quality of this section has led to the suggestion that the first chapter was combined with the last two to form a liturgy for use in the New Year festival in the autumn of 612 after the fall of Nineveh.3

The last chapters employ forceful, descriptive terminology to create a compact, vivid word picture of the confusion and horror during the Babylonian attack. In Nahum’s thought, God acts against an enemy who has earned punishment and wrath. The closing, mocking verses, indicate that the battle was over and the quietness of death and desolation had descended upon the city and its leaders. All who suffered the cruelty of Assyrian tyranny clap their hands in rejoicing (3:18-19).

It has also been proposed that the book was developed to propagandize, to encourage a strong stand against Assyria and to extend hopes for the restoration of the nation of Judah.4 It seems better and simpler to recognize the book of Nahum as consisting of genuine oracles by the prophet concerning the fall of Nineveh, to which an introductory poem was added to adapt the total work to liturgical usage.5

THE GROWTH OF NEO-BABYLONIAN POWER

Not all of the old Assyrian empire bowed to Babylon. A young Assyrian prince was made king and an invitation was sent to Pharaoh Necho of Egypt to join in stopping the growth of the new Babylonian empire. As Necho moved northward to join his allies, Josiah, perhaps in an attempt to protect Judah from both Assyrian and Egyptian control, attempted to stop him and was killed in the battle of Megiddo. Necho proceeded into Syria and Josiah’s son Shallum, or Jehoahaz (possibly his throne name), took the throne, supported by the free men of Judah. Within three months he was deposed by Necho and taken as a hostage to Egypt. His brother Eliakim was appointed king and his name changed to Jehoiakim.6

The Babylonian army, led by Nabopolassar’s son Nebuchadrezzar (the Nebuchadnezzar of the Bible), defeated the Assyrians and Egyptians at Carchemish in 605. Fleeing Egyptians were pursued to their own borders and only saved from invasion by the death of Nabopolassar which necessitated Nebuchadrezzar’s return to Babylon. He was crowned king in April, 604.

In Judah, Jehoiakim, having promised allegiance to Babylon, retained the crown. He was an unpopular ruler and Jeremiah makes reference to his extravagance in building a new summer palace at Bethhaccerem (Ramat Rahel), a hill site a few miles south of Jerusalem.7 Jeremiah also refers to the brutal and tyrannical role that Jehoiakim played, thus suggesting that he was anything but esteemed.

The Egyptian-Babylonian power struggle had not been completely settled and in 601 the two nations met again. Apparently the battle was a stalemate, and Nebuchadrezzar returned to Babylon to strengthen his forces. Possibly the failure of Nebuchadrezzar to win a decisive victory encouraged Jehoiakim to make a fatal error and rebel against Babylon. At the time, Nebuchadrezzar was engaged in a frontier struggle and it was not until late in 598 that Babylonian armies moved on Jerusalem. During that same month Jehoiakim died, passing his problems to his 18-year-old son Jehoiachin.8 The siege of Jerusalem began on December 18, 598 and the city was taken on March 16, 597.9 The temple was looted and Jehoiachin and leading citizens and artisans were taken as prisoners to Babylon. Jehoiachin’s uncle Mattaniah, whose name was changed to Zedekiah, was appointed king over a nation once again suffering from the ravages of war. Nebuchadrezzar had not only attacked Jerusalem, but Jehoiakim’s new summer palace and the cities of Debit and Lachish all bear archaeological witness to Babylonian demolition.

HABAKKUK

The new threat to Judaean security in the rise of Babylonian power, the evil of Jehoiakim’s rule, and the faltering of the Josianic reform produced turmoil in the mind of the prophet Habakkuk whose cry, "O Yahweh, how long?" introduces his collected oracles. Nothing is known of the man beyond the editorial note that he was a prophet (1:1). Many scholars have surmised that he may have been a Jerusalem cult prophet, for the notations in Chapter 3 suggest that his words may have been used in the temple liturgy.10 A legend preserved in Bel and the Dragon11 seems to be void of historical content. Habakkuk is not a Hebrew name and may be derived from an Assyrian word for a plant or herb ( hambakuku).

It is difficult to date with certainty the time of the oracles. The only real clue is the reference in 1:6 to the Chaldeans as the instrument of Yahweh’s judgment, and even this passage has been given different interpretations. The German scholar B. Duhm argued that "Chaldean" should be changed to read "Kittim," a term originally used with reference to the people of Cyprus but later applied to the Greeks and Romans. Duhm believed that Habakkuk was written in the late fourth century in the time of Alexander the Great.12 A first century B.C. scroll of Habakkuk, containing only the first two chapters and an interpretive commentaryl3 found at Qumran, reads "Chaldeans" in 1:6 but employs the word "Kittim" when applying it to their own day. It is clear that in the Qumran literary tradition the original meaning was "Chaldean." If those who suffer at the hands of the Chaldeans are Assyrians, as some have suggested, the book is to be dated in 625 when Nabopolassar revolted, or near 612 when Nineveh fell.14 On the other hand, if it is Judah that is to suffer at the hands of the Babylonians and if some of the references in Chapter 2:9 ff. can be related to the actions of Jehoiakim, then a date between 609 and 598 B.C. is preferable. The latter interpretation seems to fit the situation best, and if the prophet’s anticipation of a Babylonian attack was prompted by Jehoiakim’s efforts to achieve independence, then a date after 601 seems most appropriate. The fact that the Egyptians are not mentioned may indicate that the oracles are from 598.

Two titles (1:1, 3:1) divide the book. The first two chapters include oracular statements; the last chapter, entitled "a prayer of Habakkuk," is a hymn. For clearer analysis the book can be divided as follows:

- 1:1-2:5 The prophet’s dialogue with Yahweh.

- 2:6-20 Oracles of woe.

- 3:1-16 A theophanic hymn of praise to Yahweh for past victories.

- 3:17-19 A statement of trust.

Read 1:1-2:5

The first section opens with a query to Yahweh (1:2-4), in whose control lay the destiny of Judah. The Josianic reform had led to genuine efforts to observe Yahweh’s will as revealed in Deuteronomy, but Josiah had died in battle and his successor, Jehoiakim, was a tyrant. Now, the emphasis on the observance of law ( torah) had slackened and the ancient problem of the perversion of justice and the oppression of the righteous by the wicked was as acute as it had ever been. The cry, "Violence," which was an appeal to Yahweh to deliver, went unheeded. How long, asked Habakkuk, could a righteous deity tolerate this situation?

Yahweh’s answer (1:5-11) was that the instrument of justice was to be the Chaldeans, despite the fact that they did not recognize Yahweh’s role in their conquest (1:11). It seems clear that the Babylonians were on the march.

The answer shocked the prophet. How could a pure and holy deity use a people as ruthless and unrighteous as the Chaldeans to punish Judah, a people that, despite their evil ways, were more righteous than the Babylonians? How long would Yahweh permit the Chaldeans to enslave people (1:12-17) ? The prophet went to a tower to "see" how Yahweh would reply.

The answer came in the form of a command and a statement of reassurance (2:2-5). The prophet was ordered to inscribe on a tablet, in letters large enough so that a fleeing man could read it without stopping his flight, the message that the end was at hand. The just or righteous, he was assured, would "live by his faith" or "faithfulness." The meaning of this statement is not clear. Does it mean that the righteous man would, could or should live with steadfast, unyielding, moral courage, knowing that he is right-small comfort if the enemy kills without discrimination-or does it mean that the righteous man should live in the faith that Yahweh would deliver him from the enemy because of his faithfulness to Yahweh’s way?15 The prophet introduced the problem of theodicy,16 the righteousness of Yahweh, which was to be discussed over and over again by subsequent writers.

Read 2:6-20

The woe oracles seem to be directed against specific individuals. The person indicated in the first oracle (2:6-8) cannot be identified, but the reference to plunder may indicate the Babylonians. The second (2:9-11) and third (2:12-14) fit what we know of Jehoiakim, whose construction of a summer palace placed heavy burdens on his countrymen.17 The remaining oracles condemn drunkenness and idolatry, and a liturgical statement closes the section.

Read 3:1-19

Whether or not the hymn and statement of trust are the work of Habakkuk cannot be determined. This chapter is missing in the Qumran scroll, but this fact, in itself, proves nothing. The chapter stands apart from the rest of the book in its hymnic quality, and although it has been interpreted as the answer to the question posed in 2:1-3,18 in reality only the statement of trust (3:17-19) is applicable. The liturgical notations "according to Shigionoth"19 (3:1), "Selah"20 (3:3; 9:13) and the final word to the "choirmaster"21 suggest that a hymn and confession of trust (3:17-19) borrowed from cultic ritual have been added to Habakkuk’s work to adapt it to liturgical usage. The imagery of the hymn is reminiscent of a lost myth of a battle between Yahweh and the sea, similar to that of the struggle between Ba’al and Yam (3:12-15). The theophany is like that in Judg. 5 (cf. 3:3 ff.), but is more elaborate and introduces new mythological motifs. It has been suggested that the chapter is the product of the seventh century, that it employs archaizing techniques, and that it is the work of one writer, possibly Habakkuk the prophet.22

THE LAST DAYS OF JUDAH

Zedekiah’s rule was a tenuous one. Jehoiachin, the king in exile, was treated as a royal hostage and Babylonian tablets recording the allotment of provender to the monarch (listed as "Yaukin of Yahud") and his family have been found, confirming the note in II Kings 25:29 f. Moreover, Jehoiachin retained his holdings in Judah, for storage jars bearing the stamped seal of "Eliakim, steward of Jehoiachin" have been found, indicating that financial returns from Judah holdings were garnered in the name of the absentee king.23 The portrait of Zedekiah preserved in Jeremiah’s words depicts him as a vacillating, rather weak ruler not fitted for the delicate responsibilities of his age. Whatever his character may have been, he failed to recognize and appreciate, as Jeremiah apparently did, the master statesmanship and military skill of Nebuchadrezzar.

A revolt in Babylon, perhaps led by certain elements of the army, may have caused Zedekiah to believe that Nebuchadrezzar’s power was crumbling, and it would appear that the Jerusalem prophet Hannaniah furthered this hope (cf. Jer. 28:1 ff.). It is possible that some of the exiles were restless, for Jeremiah wrote them a letter urging them to be good citizens (Jer. 29). A cooperative plan of revolt was developed by small nations, including Edom, Moab, Ammon, Tyre and Sidon, and Zedekiah was urged to ally himself with them (Jer. 27). Zedekiah refused but later that same year (594), the Pharaoh Hophra of Egypt attacked Philistia in an attempt to regain control of territory important for trade and shipping and Zedekiah joined this rebellion. Once again Nebuchadrezzar moved on Jerusalem and, after an eighteen-month siege beginning in late December, 588 or January, 587, took the city in August, 586.24 These were disastrous months for Judah. Babylonian armies ravaged nearby cities, including Debir and Lachish.25 From the excavation of Lachish, twenty-one ostraca26, have been recovered consisting of correspondence between a scout or soldier in charge of an outpost and an officer within the city, written about the time the siege of Jerusalem was about to begin.27 Some letters are so indistinct and fragmentary that their meaning is obscure, but others are quite clear. They speak of those who hinder and weaken and they invoke the name of Yahweh and refer to "fire-signals" by which information was relayed. Shortly afterward the Babylonian armies destroyed Lachish and other Judaean cities. The siege of Jerusalem is related briefly in II Kings 25:1-21 (cf. Jer. 39:1-10). The city was without food and when the Babylonians finally entered, Zedekiah and his soldiers fled. Zedekiah was captured and brought for judgment before Nebuchadrezzar who was in Syria. His fate was worse than death. His family was murdered one by one before him, and then Zedekiah was blinded so that the last sight he would remember would be the destruction of his loved ones. In chains he was led to Babylon. The city of Jerusalem was utterly destroyed: the temple of Solomon was pulled down, the walls of the city were demolished and buildings were set afire.

Once again Babylonian soldiers took into captivity what remained of skilled or talented leadership, leaving only the poor and the underprivileged. So great was the devastation of Jerusalem that governmental headquarters were moved to Mizpah, probably Tell en-Nasbeh a few miles north and west. A certain Gedaliah was placed in charge of Judah.28 Little by little, as Babylonian soldiers withdrew, refugees returned, including Judaean soldiers. Encouraged by the king of Ammon, one of these men, named Ishmael, murdered Gedaliah. Pursued by angry Judaean warriors, Ishmael went to Ammon. In fear of reprisal from Babylon, many Judaeans fled to Egypt, compelling Jeremiah and his scribe to accompany them. The tattered remnant predicted by the prophets remained in Judah. In Babylon, another remnant of the educated, informed and talented kept alive faith in Yahweh and the fierce nationalism that was to be the rebirth of the people of Judah, the Jews.

JEREMIAH

Some insight into the last tumultuous trouble-ridden days of Judah comes from the book bearing the name of the prophet Jeremiah. According to the editorial superscription (1:1) Jeremiah was the son of Hilkiah, a priest of the village of Anathoth a few miles northeast of Jerusalem.29 Unlike Isaiah and Hosea, Jeremiah remained unmarried (16:2). The superscription notes that he received his summons to prophesy in the thirteenth year of Josiah (cf. 25:3) or about 627/626 B.C., leading to the hypothesis that he may have been born about 650 or, in view of the prophet’s complaint that he was too young for prophetic responsibilities (1:6), between 650 and 640.30 Many scholars have proposed that his first oracles, which dealt with an enemy from the north (1:11-19), are to be associated with the movement of the Scythians, but others, including J. P. Hyatt, have argued that the foe from the north is to be identified as Neo-Babylonian,31 and that the thirteenth year of Josiah was the date of Jeremiah’s birth, for Jeremiah speaks of Yahweh consecrating him while he was still in the womb (1:5).32 Because, to the best of our knowledge, the Scythian threat was not realized and the Neo-Babylonian one was, it is attractive to accept the latter theory. However, references to Jeremiah’s wrestling with his call from Yahweh can hardly be considered prenatal and the implications of the superscription (and 25:3) should not be ignored. The superscription goes on to say that Jeremiah continued to prophesy until the eleventh year of Zedekiah (587), but events subsequent to this date appear in Chapters 40-44, a separate source. Jeremiah’s prophetic ministry extends over a period of more than forty years.

Passages recording Jeremiah’s personal response to his work, his loneliness and sense of frustration, and the vituperative attitude of his countrymen tend to create in the reader a feeling of genuine intimacy and empathy beyond that experienced with other biblical writers. Jeremiah’s sensitivity to nature, his allusions to village life, and his changing moods are recorded in poetry charged with emotional power and illuminated by vivid imagery (cf. 4:20-21, 29; 6:24; 8:18). His deep religious awareness, his sense of personal relationship with Yahweh, his outcries and protests yet his constant yielding to what he understood to be divine will reveal the emotional depth of his experiences. He appears as one upon whom the waning fortunes of the nation, the callous indifference to community welfare of Jehoiakim, and the apostasy of the people laid a heavy burden and produced emotions akin to physical torment (4:19 f.). Yet, when Babylonians removed the leading citizenry, Jeremiah rose above his personal situation to direct words of wisdom and guidance to those being led by false hopes to anticipate an early return to Judah (ch. 29).

Despite his loneliness, Jeremiah had at least one disciple, Baruch, son of Neriah, who copied the prophet’s oracles and delivered them to King Jehoiakim (ch. 36). It is possible that the bulk of the record of Jeremiah rests upon Baruch’s work.

Traditionally the entire fifty-two chapters of Jeremiah have been attributed to the prophet, but it is clear that such a thesis is no longer tenable. There is a considerable difference between the Hebrew and the LXX texts, not only in the order of the contents but in length. The LXX version is shorter, omitting numerous individual verses but adding others, raising a question as to whether passages were dropped from the LXX tradition or added to the Hebrew. Chapter 52 of Jeremiah parallels II Kings 24:18-25:21 and is a summary of events from 598 to 566, from the same source as II Kings. Chapters 50 and 51 come from a period after the destruction of Jerusalem but before the death of Nebuchadrezzar in 562 and represent the time when the captive Judaeans, or Jews as they came to be called, dreamed of the overthrow of Babylon by an enemy vaguely defined as a foe from the north or, at times, as the Medes. Certain eschatological and restoration oracles represent the thinking of the people of the Exile and are, therefore, additions to Jeremiah’s work: 3:14-18; 4:23-26; 12:14-17; 16:14-15; 23:1-4, 5-6, 7-8; 25:30-38; 30:8-9, 10-11, 16-17, 18-22, 22-24; 31:1, 7-9, 10-14, 23-25, 27-28, 35-37, 38-40. Numerous passages in Chapters 26-45 relating Jeremiah’s activities in the third person may represent Baruch’s memoirs. Therefore, the book is composite, containing genuine Jeremiac sayings, Baruch’s contributions and later additions.

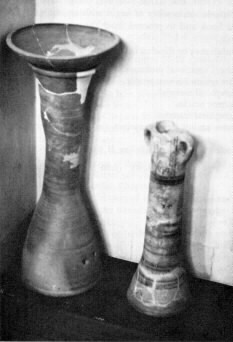

INCENSE ALTARS from the Early Iron Age found at Megiddo, perhaps similar to those used in Jeremiah’s time to burn incense to Ba’al (cf. Jer. 1:16; 7:9; 11:12 f.; etc.)

INCENSE ALTARS from the Early Iron Age found at Megiddo, perhaps similar to those used in Jeremiah’s time to burn incense to Ba’al (cf. Jer. 1:16; 7:9; 11:12 f.; etc.)

Chapter 36, which tells of a scroll dictated by Jeremiah to Baruch for presentation to King Jehoiakim, is usually taken as the starting point for study of the literary tradition. The king destroyed this scroll but Jeremiah immediately dictated another containing the same material and numerous additions (36:32). The contents appear to have been the accumulated oracles of the prophet, including those denouncing "Israel and Judah" and foreign nations (36:2). Some attempts have been made to isolate this scroll from the total work assigned to Jeremiah, but results have not been particularly satisfactory.33 The basis for selections are that the material must represent oracles from 626 to 605 and that they must be composed of indictments and threats. The choice of oracles is generally limited to Chapters 1 to 25. Just how helpful such lists are is not clear. The problem is complicated by the Deuteronomic style which appears in varying degrees in Jeremiah’s work, for it is not clear to what extent Jeremiah may have adopted or employed a Deuteronomic style (which could have become popular after 621), or to what degree his work has been edited by Deuteronomists, or to what extent his scribe, Baruch, may have utilized Deuteronomic patterns. It seems wiser to begin with an analysis of the entire content of the book and to proceed from there on an historical basis, so far as possible.

The book of Jeremiah may be divided into seven parts:

I. Ch. 1 The prophet’s vocational summons.

II. Chs. 2-25 Oracles against his own people.

III. Chs. 26-29 Biographical material.

IV. Chs. 30-33 Prophetic oracles.

V. Chs. 34-45 Biographical material.

VI. Chs. 46-51 Oracles against foreign nations (in the LXX these follow Chapter 25).

VII. Ch. 52 An historical appendix paralleling II Kings 24:18-25:21.

A more detailed breakdown follows (non-Jeremiac material is italicized) :

I. The Vocational Summons: Chapter 1.

1:1-3 Editorial superscription.

1:4-10 The call to be a prophet.

1:11-12 The vision of the almond rod.

1:13-19 The vision of the boiling pot.

II. Oracles against his own people: Chapters 2-25.

2:1-3:5 Oracles against Judah.

3:6-13 Oracles on apostasy of Judah which reflect D styling.

3:14-18 Restoration oracles loosely combined.

3:19-20 A lament.

3:21-24 Indictment in form of situation (21-23) and response (24-25).

4:1-6:30 The foe from the north (5:18-19 may be a late Deuteronomic expansion).

7:1-8:3 The temple sermon (colored by D styling).

8:4-9:11 Concerning Judah and Jerusalem.

9:12-16 An expansion by Deuteronomists.

9:17-19 A funeral dirge.

9:20-22 Laments.

9:23-24 An isolated oracle.

9:25-26 A late addition.

10:1-16 Late material in the style of II Isaiah (6-8, 10 are not in the LXX and 11 is an Aramaic intrusion).

10: 17-25 The destruction of Jerusalem (Verse 25 is a psalm fragment, cf. Ps. 79:6 f.).

11:1-17 Jeremiah and Deuteronomy (Deuteronomic styling).

11:18-12:13 The persecution of Jeremiah (Verse 13 is an isolated fragment).

12:14-17 A late restoration oracle.

13:1-14 Symbols and parables.

13:15-15:21 Oracles of disaster.

16:1-9 The loneliness of Jeremiah.

16:10-18 A Deuteronomic expansion.

16:19-21 Fragments.

17:1-18 A mixture: 1-4 is not in the LXX, 5-8 is hymnic, 9 f. and 11 are wisdom sayings, 12-13 is a fragment on the temple and 14-18 is a monologue.

17:19-27 A late defense of the Sabbath.

18-22 Miscellaneous oracles (18 and 21 reveal Deuteronomic editing).

23:1-8 Late oracles.

23:9-25 Miscellaneous oracles-25:3-9 seems to be a summation of Jeremiah’s work.

III. Biographical material: Chapters 26-29 (probably the work of Baruch).

26 The temple sermon (cf. ch. 7).

27 The prophet advises submission to Babylon.

28 Jeremiah and the false prophets.

29 The letter to the Exiles.

IV. Prophetic Oracles: Chapters 30-33.

30-31 Words of comfort (30:8 f., 10 f., 16-24; 31:1, 7-14, 23-28, 35-40 are late materials).

32 Jeremiah’s faith in the future.

33:1-5 A prediction of doom.

33:6-26 Late material (14-16 are not in the LXX).

V. Biographical material: Chapters 34-45.

34 The time of the siege of Jerusalem.

35 Jeremiah and the Rechabites.

36 Jeremiah’s scroll.

37-43 The last days of Judah.

44 Jeremiah on Egypt.

45 Jeremiah’s complaint.

VI. Oracles Against the Nations: Chapters 46-51.

46 Against Egypt.

47 Against the Philistines.

48 Against Moab.

49:1-6 Against Ammon.

49:7-22 Against Edom.

49:23-27 Against Damascus.

49:28-33 Against the Arabs.

49:34-39 Against Elam.

50-51 Against Babylon (post-Jeremiac).

VII. An Historical Appendix: Chapter 52.

JEREMIAH AND JOSIAH

Read Ch. 1

626. Jeremiah’s commission to prophesy came at a moment of dramatic restlessness in the Near East when the death of Ashurbanipal, the Chaldean-Medean power bloc and the migrations of Cimmerians and Scythians caused concern for national safety in Judah. Jeremiah’s record of his summons by Yahweh conveys his conviction that he was chosen, predestined for his prophetic role before he was born, and that the call to prophesy came before he felt he was old enough for the task. The expression of inadequacy is reminiscent of Moses’ protestations (cf. Exod. 3:9 ff., E), but like Moses, Jeremiah was assured that Yahweh’s strength would sustain him.34 The words which he was to utter were Yahweh’s words, charged with divine power, capable of building up, should the pronouncement be favorable, or destroying kingdoms, should the oracle be destructive. The same theological conviction we have seen in other prophetic writings undergirds this statement, for whatever happened for weal or woe could be traced to Yahweh and the deity’s reaction to Judah’s fidelity or apostasy. Although Jeremiah was commissioned as a prophet to "the nations," his real mission was to Judah.

The first visions are associated with everyday objects transformed in the prophet’s mind to symbols. The branch of the almond tree, shaqed in Hebrew, becomes shoqed or "watching" to the prophet and brings a promise that Yahweh was watching over his word. A boiling pot tipped toward the south becomes a warning that hordes of enemies would pour out of the north into Judah. If the reference is to the Scythian-Cimmerian movement, then Jeremiah was wrong; if it has a longer time significance then the Neo-Babylonians proved him to be right; or if these oracles are to be dated fifteen or twenty years later, as Hyatt has proposed, then Jeremiah was correct.

Read 2:1-3:20

Oracles condemning Judah for apostasy may be associated with the early period of Jeremiah’s prophetic ministry and reflect the socio-religious situation prior to Josiah’s reform. The impression of Hosea’s marriage symbolism upon the young prophet is discernible in 2:2. In 2:4 the familiar law court setting is employed with Yahweh, the plaintiff, presenting the issue (2:5), reciting the history of the case (2:6-9), presenting the uniqueness of the violation (2:10-13), appealing to the precedent of Israel (2:14-15), warning against present policy (2:16-19), and, finally, drawing upon Isaiah’s vineyard parable and Hosea’s imagery, presenting a long summation in which the arguments of the defendant are refuted. A prose summary, possibly prepared by Baruch, places this kind of condemnation in the reign of Josiah. Yahweh’s lament over the apostasy of the nation follows (3:19-20).

Read 3:21-4:4

An indictment (21) followed by a recital of penitence (22) may be derived, in part, from some liturgy utilized at a Yahweh shrine or may be Jeremiah’s idealization of what the people’s attitude should be. The setting is the autumn, the time of the New Year, when mourning for the dead Ba’al and rites of purgation were observed. Yahweh’s call (22a) evokes a penitent response, a promise of return, a rejection of the way of Ba’al (22-23) and a confession of the sin of apostasy (24-25). Yahweh’s rejoinder is a demand for a radical change of attitude and commitment (4:4), upon which potential blessings rest (4:1-2).

Read 4:5-6:30

The collection of fragments of war oracles may be associated with the Scythian threat and reveal something of the physical and mental suffering of the prophet as he envisions the disasters. So complete is the devastation pictured by the prophet that the earth is returned to its primeval emptiness (4:23 ff.). Chapter 5 introduces a literary pattern of statements and responses. Yahweh comments upon the impossibility of finding a faithful follower (5:1-3). The prophet responds that they are discussing only the poor, but when he looks among the rich and powerful he discovers only infidelity (5:4 f.). The result is condemnation by Yahweh and the threat of complete destruction.

A COSMETIC MORTAR. The cosmetic mortar pictured here is from the time of Jeremiah and was found at Tell en-Nasbeh which is believed to be the biblical city of Mizpah (Jer. 40:6 ff.). Cosmetic mortars were usually made from limestone or marble and were from three to four inches in diameter. Fragments of green malachite ore were placed in the mortar and ground to a fine powder with a pestle, then oil was added to make a paste and the green eyeshadow called kohlor kuhl was applied to the eyelids. A black cosmetic preparation for eyebrows, eyelashes and for outlining the eyes was made by grinding antimony to powder and adding oil. It was the use of these products that Jeremiah had in mind when he described Jerusalem as a harlot enlarging her eyes with paint (Jer. 4:30). A reddish colored cosmetic mixture was made by using iron oxide as a base.

A COSMETIC MORTAR. The cosmetic mortar pictured here is from the time of Jeremiah and was found at Tell en-Nasbeh which is believed to be the biblical city of Mizpah (Jer. 40:6 ff.). Cosmetic mortars were usually made from limestone or marble and were from three to four inches in diameter. Fragments of green malachite ore were placed in the mortar and ground to a fine powder with a pestle, then oil was added to make a paste and the green eyeshadow called kohlor kuhl was applied to the eyelids. A black cosmetic preparation for eyebrows, eyelashes and for outlining the eyes was made by grinding antimony to powder and adding oil. It was the use of these products that Jeremiah had in mind when he described Jerusalem as a harlot enlarging her eyes with paint (Jer. 4:30). A reddish colored cosmetic mixture was made by using iron oxide as a base.

JEREMIAH AND DEUTERONOMY

Read Chs. 11-12

The most important socio-religious event of Josiah’s reign was the discovery of the Deuteronomic scroll, but it is difficult to assign passages in Jeremiah to this subject with any certainty. Chapter 11 may be a Deuteronomic essay inserted in Jeremiah’s work to make the prophet appear as a supporter of the code.35 It is possible that it contains an historical kernel.36 On the other hand, if Jeremiah did support Deuteronomy, it is not impossible that he used D language in urging its support and in proclaiming its contents.37 It has also been argued that Jeremiah is not referring to the D covenant code but to the Sinai covenant.38 The first five verses echo the curse of Deut. 27:26 as well as the familiar Deuteronomic recitation of the past. Verses 6-13 tell of Jeremiah’s commission to support the code and of the failure of his mission. Verses 14-17 refer to Yahweh’s rejection of his people. The monologue which follows (18-20) portrays the hostility of those refusing the message and, in 21-23, the opponents are identified as men of Anathoth, Jeremiah’s birthplace, where Deuteronomic legislation would affect the future of the Yahweh shrine (or any other) and the priesthood.

A second monologue raises the problem of theodicy39 (12:1) and mentions the rejection of the prophet by his own family. Yahweh’s response to the query about theodicy is Yahweh’s promise of the destruction of the nation and the abandonment of his temple. Without Yahweh the nation could have no inner strength; indeed, Yahweh’s sword was to be turned against his chosen people (12:12). On the basis of these chapters it could be argued that Jeremiah supported the Deuteronomic reform with enthusiasm, that he encountered bitter opposition in his home community when he attempted to preach there, and that his efforts to bring about the reform were unavailing (cf. Jer. 15:16 f.).

Other passages may be selected to reflect another response. For example, Jeremiah 8:8 ff. may refer to the prophet’s rejection of D as a false work by the scribes, or this passage may be interpreted as a reflection of Jeremiah’s attitude after his work on behalf of the code failed. Whatever Jeremiah’s original response to D may have been,40 if 31:31 ff. is by the prophet as most scholars believe it is quite clear that Jeremiah became convinced that the formalizing of religion in a covenantal code or in a rigid credal statement was inadequate. He returned to the emphasis of his prophetic predecessors and stressed a religion of inner commitment rather than outer observance. The covenant of the future would be inscribed on the human heart rather than on tablets of stone, and knowledge of God would not be knowledge about Yahweh acquired through teaching but inner, personal knowledge gained through experience.

JEREMIAH AND THE DEATH OF JOSIAH

Read 22:10-12; 8:14-15

609. The death of the king and the capture of Jehoahaz seems to have been the occasion for the remarks in 22:10-12. Jeremiah correctly ascertained that Jehoahaz would never return to the throne of Judah. The words of despair in 8:14 f may also be from this period.

JEREMIAH AND JEHOIAKIM

Read Chs. 7, 26

Soon after Jehoiakim became king, Jeremiah prophesied the destruction of the temple of Yahweh, the symbol of national unity and security. His words, preserved in the so-called "temple sermon" (ch. 7), provoked a violent response and a threat of death. Indeed, in Baruch’s record (ch. 26) we are told that a fellow prophet, Uriah, fled to Egypt after preaching much the same message, only to be extradited and executed. Jeremiah escaped a similar sentence through protection by the politically powerful Ahikam, son of Shaphan, the royal secretary (cf. Jer. 26:24; II Kings 22:8 ff.). The rejection of Deuteronomic cultic rules is clear from Jeremiah’s words about families participating in the worship of the queen of heaven (7:18) and in child sacrifice (7:31).

Read 19-20:6; 36:9-32

A second sermon is reported, probably by Baruch, in what is often referred to as the "Tophet sermon." The breaking of the clay flask was a ritual act carrying with it symbolic meaning and divine power.41 For this prophetic act Jeremiah was beaten and placed in stocks by Pashhur, a temple official. Whatever discouragement the prophet may have experienced in punishment and public disgrace did not prevent him from continuing to make his message heard. In December, 604, during a public fast, a scroll prepared earlier was read to the people in the temple precincts, then read to the princes, before being delivered to the king. As Jehoiakim listened to the words, with derisive contempt he burned the scroll, piece by piece, showing utter disdain for anything Jeremiah might have to say. The prophet immediately reproduced the scroll in an expanded form, providing, as we have noted previously, what may be the nucleus of the present book of Jeremiah.

Read 22:13-23; 45

Jehoiakim’s building program, his indifference to the plight of the poor, his use of violence and his greed were, in part, the bases for Jeremiah’s hostility to the king. The ruler’s death in 598 produced little sorrow in the prophet.

Read Ch. 25; Chs. 46-47

Outside of Judah the Near Eastern world was in turmoil. Necho’s abortive efforts to halt Nebuchadrezzar at Carchemish convinced Jeremiah that the Neo-Babylonian Empire was destined to become the dominant world power. Any attempt at retaliation by Egypt, he prophesied, would fail. During the time of his struggles with Jehoiakim, he turned his attention to the surrounding nations and pronounced a series of doom oracles. A summary list of the nations against which he hurled his condemnations is given in 25:17 ff., perhaps by Baruch. Statements against these nations are found in Chapters 46-49. It is probable that the basic material in these oracles is by Jeremiah, but there can be little doubt that his work was expanded by later hands. The oracle against Egypt predicts the failure to meet Nebuchadrezzar’s threat of world domination and the words against Philistia are made to foretell an attack by Necho.

Read Chs. 48-49

How much of the oracle against Moab can be accepted as Jeremiah’s work is hard to determine. It is possible that this pronouncement may have been given in 602 when Jehoiakim rebelled against Nebuchadrezzar and suffered attack by Moabites, Ammonites, Syrians and Chaldeans (II Kings 24:2 ff.). Another possible date is in the time of Zedekiah (cf. Jeremiah 27:1-11). The oracle contains a remarkable roster of Moabite communities. The Ammonite oracle, less vehement in character, is no less positive in its prediction of destruction, and the words directed against Edom contain condemnations and promises of desolation. The oracles against Damascus (49:23-27) are probably not by Jeremiah, for Damascus had ceased to be a problem since the Assyrian conquest. It is possible that there is a genuine core of Jeremiah’s words in the condemnation of the Arabs (49:28-33).

JEREMIAH AND JEHOIACHIN

Read 13:18-19; 22:24-30

The brief reign of Jehoiachin receives only passing mention by Jeremiah. Even as the young king took control of the kingdom, the Babylonians were occupying the surrounding country. There could be no doubt that Jeremiah’s prophecies of the fall of the city were to be fulfilled. As Jehoiachin (or Coniah) was taken into exile, Jeremiah predicted that none of his descendants would occupy the throne of Judah.

JEREMIAH AND ZEDEKIAH

Read Ch. 24

Much of the recorded work of Jeremiah relates to Zedekiah’s time. Immediately after Nebuchadrezzar’s hosts had departed, taking with them the cream of Judah’s artisans and leaders, Jeremiah expressed his lack of confidence in Zedekiah’s ability to save the nation from ultimate destruction. On the other hand he saw in the exiles the hope of the future, and introduced into biblical thought an idea that was to be expanded by subsequent writers-that the true Israel was to be found among these exiles (24:4-7).

Read Chs. 27-29

Apparently some of Jeremiah’s countrymen had not been impressed by Babylonian power, possibly because the city and the temple were not destroyed in the first siege. Jeremiah had no such illusions and warned against false confidence in Judah’s ability to evade Nebuchadrezzar’s yoke. Oracles by the prophet Hananiah, predicting a triumphant return of the people and plunder seized by Babylon, provoked Jeremiah to a dramatic portrayal of servitude in which he donned a neck-yoke. Messages sent to the exiles promising restoration and return were countered by Jeremiah in a letter wisely advising the captives to prepare calmly and intelligently for a lengthy absence from Judah and to seek their personal welfare in the prosperity of Babylon.42 Jeremiah’s letter (Read Chs. 34; 37-40) suggests that the exiled Judaeans lived in their own community, owned their own homes, cultivated their own gardens and apparently experienced no major suffering or inconvenience. (Yet, cf. Psalm 137.)

When Zedekiah’s folly brought about the return of Nebuchadrezzar’s army, Zedekiah, in a desperate effort to win Yahweh’s favor and support, declared the release of all Hebrew slaves in accord with Deuteronomy 15. The covenantal requirement was no sooner announced than it was violated, and the newly freed slaves were taken back into bondage. The armies of Babylon arrived. During a lull in the siege, Jeremiah attempted to visit his home in Anathoth but was arrested as a deserter and imprisoned in a cistern empty of water but not of miry sediment. When he was rescued from this cell and brought before Zedekiah, he advised surrender to Babylon-counsel that the monarch rejected. After the fall of the city when the second deportation took place, Jeremiah was permitted to remain in Judah.

JEREMIAH AFTER THE DESTRUCTION OF JERUSALEM

Read 40-44

After the murder of Gedaliah, there were those who determined that the only way to be safe from punishment by Nebuchadrezzar was to seek refuge in Egypt. Jeremiah sought to dissuade them, but they were determined to flee, and when they departed they took with them Jeremiah and his scribe, Baruch. In Egypt, Jeremiah is reported to have prophesied the fall of Egypt to Nebuchadrezzar.

JEREMIAH’S CONFESSIONS

A number of monologues in which Jeremiah reveals his inner emotions and personal communications with Yahweh are labeled "Confessions." They include: 11:18-23; 12:1-6; 15:10-12, 15-21; 17:910, 14-18; 18:18-23; 20:7-12, 14-18.

The youthful naiveté with which the prophet entered his career, the resultant suffering at the hands of his opponents (including his own family), his loneliness and isolation from the ordinary joys of his countrymen, and his frustration and cries for vengeance, depict the inner turmoil of the prophet. His experiences, which caused him real physical pain, grew out of a commitment to Yahweh which both delighted him (15:16) and isolated him from pleasures of society. Doubts about Yahweh’s constant support (15:18b) were answered with the guarantee of fortifying strength (15:19 ff.). As he became the subject of mockery and ridicule, he determined never to utter the oracles of Yahweh again, only to find that the fire of Yahweh’s demands burned within him, compelling him to cry out his words of doom against his will, so demanding was the power of his experience of the divine (20:7 ff.). Fluctuating moods, anger, demands for vengeance, coupled with moments of strength and assurance, mark him as the most human of men, an individual torn between destiny, duty, a committed life, and the pressures of an unsympathetic, hostile audience.43

HEAD OF A GODDESS. Figurines of clay, often called "Astarte figurines," have been found by archaeologists at many sites in Palestine in material remains coming from the period of the divided kingdom (Iron II). The face or front of the head was formed by pressing soft clay into a carefully prepared mold. The back of the head was roughly shaped by hand. The body consisted of a solid pillar of clay, flared at the base so it could stand alone. Usually the breasts were prominent and the arms, formed of strips of rolled clay, are flattened at the end to form hands which may merge into the body beneath the the breasts or cup or support the breasts as though offering them to an infant. Such representations are called dea nutrix or "the nurse goddess," symbolizing the mother who feeds her children. It is quite possible that these figurines are representations of the "queen of heaven" favored by the women of Jerusalem in Jeremiah’s time (Jer. 7:16-20; 44:16-19).

HEAD OF A GODDESS. Figurines of clay, often called "Astarte figurines," have been found by archaeologists at many sites in Palestine in material remains coming from the period of the divided kingdom (Iron II). The face or front of the head was formed by pressing soft clay into a carefully prepared mold. The back of the head was roughly shaped by hand. The body consisted of a solid pillar of clay, flared at the base so it could stand alone. Usually the breasts were prominent and the arms, formed of strips of rolled clay, are flattened at the end to form hands which may merge into the body beneath the the breasts or cup or support the breasts as though offering them to an infant. Such representations are called dea nutrix or "the nurse goddess," symbolizing the mother who feeds her children. It is quite possible that these figurines are representations of the "queen of heaven" favored by the women of Jerusalem in Jeremiah’s time (Jer. 7:16-20; 44:16-19).

JEREMIAH’S CONCEPT OF GOD

From the confessions it is easy to ascertain that Jeremiah believed Yahweh to be a god of judgment and justice, reliable and sure, concerned with the people’s ethical behavior and obedience. Other passages reveal that Jeremiah emphasized the election tradition. Drawing upon Hosea, he glorified the wilderness tradition as the time when the people were faithful to their deity and argued that infidelity developed with the settlement in Canaan. What is new in Jeremiah’s teaching is the reference to the covenant which was not specifically mentioned by his prophetic predecessors, but which, under Deuteronomic influence, was brought into central focus (11:3 ff.). Judah was the chosen of Yahweh, linked not only by ties of obedience and love, but by the binding, contractual force of the covenant.

Like earlier prophets, Jeremiah emphasized moral conduct and condemned the cult (6:20), but he went much further in his mockery of those who accepted the existence of the temple as a symbol of divine protection. The centralization of the cult under Deuteronomic influence no doubt contributed to this idea, and Jeremiah’s prediction that the temple would become a ruin like the shrine at Shiloh was more than religious heresy and bordered upon treason. Jeremiah’s argument was that Yahweh could not be protector of his people when they had forsaken him and that the very symbol of his protective role had become meaningless and would be removed because of national apostasy (ch. 7). Ritual was secondary; obedience was primary. Complete commitment to Yahweh and national security went hand in hand, as did unfaithfulness and disaster.

Yahweh’s interest and power was not limited to Judah. He was creator of the world, and all human authority, all world leadership, all history was under his control (27:5 ff.; 31:35 ff.). Yahweh was god of nature, but was concerned with moral behavior (5:25 f.). Nor was the worship of Yahweh restricted to Judah or Jerusalem; Jeremiah taught that those in exile should pray to Yahweh on behalf of their captors, in the assurance that their prayers would be heard (29:7). This teaching moves beyond the monolatrous statements of Deuteronomy toward monotheism, encouraging belief in the possibility of worshipping Yahweh in any spot on the face of Yahweh’s earth, and although the first full statement of monotheism was to come over half a century later, Jeremiah’s expanded concepts provide the basis for such beliefs.

The theme of Yahweh’s redemptive love developed by Hosea is expanded by Jeremiah. The national debacle foreseen by the prophets had become a reality and the war-weary Judaeans looked toward the future. Jeremiah did not extend hope for a quick return from exile but gave the exiles a new identity as the seed of the new Israel. As Yahweh in anger had sent them away, so Yahweh in love would restore them. A new god-people relationship would be established (24:4 ff.) and a new covenant of the heart formed (31:31 ff.), a concept that would be of great significance to those in exile and unable to perform covenant rituals. So confident was Jeremiah of Yahweh’s redeeming love and of the future of the people, that at the height of the Babylonian siege he purchased a plot of ground in Anathoth from a cousin (32:6-15). Yahweh was not only god of the past, but lord of the future.

Endnotes

- The acrostic form ends with the fourteenth letter of the Hebrew alphabet which contains twenty-two consonants.

- Proposed sites include the village Elkese in Galilee, suggested by Jerome in the fifth century A.D., and the village of Elkush, north of Nineveh where the prophet’s tomb is shown, and it has also been pointed out that the name of the Galilean town of Capernaum means "village of Nahum."

- P. Humbert, "Le Problème du livre de Nahoum," Revue de Histoire et Philosophie Religiouse, XII (1932), 1-15.

- A. Halder, Studies in the Book of Nahum (Upsala: Lundequistska, 1946).

- Lindblom, op. cit., p. 253.

- As previously noted, the change of name may indicate the assumption of a "throne name." It may also symbolize the right of the conquering ruler "to name" his appointees as a symbol of his power in bringing the individual into being as a king.

- Jer. 22:13-19, cf. Y. Aharoni, "Excavations at Ramat Rahel," BA, XXIV (1961), p. 118.

- For a completely different ordering of events, cf. II Chron. 36:5 ff.

- For a succinct analysis of dating, cf. J. Finepn, op. cit., p. 222.

- P. Humbert, Problèmes du livre d’Habacuc (Neûchatel: Secrétariat de l’Université, 1944) puts the liturgy in the years 602-610.

- See below, Part Nine, chap. 30.

- B. Duhm, Das Buch Habakuk (Tubingen: J. C. B. Mohr, 1906), pp. 4-30.

- This form of commentary called pesher (because this Hebrew term signifying "this means" introduced the commentaries) was not concerned with the prophet’s meaning for his own time, but only with the prophetic significance of the words for the commentator’s own day. For a translation of the Habakkuk commentary, cf. T. H. Gaster, The Dead Sea Scriptures in English Translation (New York: Doubleday Anchor Book, 1956), pp. 246-256.

- Weiser, op. cit., p. 262.

- For a re-interpretation and a re-application of Habakkuk 2:4 in a New Testament, Christian context by the apostle Paul, cf. Galatians 3:11; Romans 1:17. For the interpretation of the Qumran community, cf. Gaster, The Dead Sea Scriptures, p. 253; James Alvin Sanders, "Habakkuk in Qumran, Paul, and the Old Testament," Journal of Religion, XXXIX (1959), 232-244.

- The word "theodicy" is made up of two Greek words theos, god, and dike, justice. The postulate of a righteous, all-powerful deity raises the question of the presence of evil in the world, and/or the reason why evil seems to be more powerful than good or why the evil triumph over the righteous.

- Cf. Jer. 22:13-17.

- Weiser, op. cit., p. 262.

- The word "Shigionoth" cannot be translated. It may refer to an instrument, to the time in the service for a song, or to the tune or mood of the music.

- "Selah" indicates an interlude, perhaps for instruments or cymbals.

- The "choirmaster" seems to have been the chief of the musicians.

- Wm. F. Albright, "The Psalm of Habakkuk" in Studies in Old Testament Prophecy, H. H. Rowley (ed.) (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1950), pp. 1-18.

- Cf. Wright, Biblical Archaeology, p. 181.

- For dates one year earlier, cf. Wright, op. cit., p. 180.

- Thi fires of Lachish were so fierce that mud-brick walls were baked a bright red.

- Ostraca are pottery sherds which have been written upon. It was a common practice to use pieces of broken pottery in this manner.

- H. Torczyner, The Lachish Letters (Lachish I) (London: Oxford University Press, 1938).

- A clay seal found at Lachish read "Property of Gedaliah who is over the house" and may have belonged to the new governor.

- There is no reason to suspect that Hilkiah of Anathoth was the priest of the same name who discovered the Deuteronomic scroll, nor can it be assumed that he was a priest of Ba’al, nor that he was descended from Abiathur, the priest banished by King Solomon to Anathoth (I Kings 2:26), as some have suggested.

- It should be remembered that Josiah was only eight years old when he became king.

- J. P. Hyatt, "Jeremiah," The Interpreter’s Bible, V, 797.

- Ibid., p. 779. For a completely different solution in which the "foe from the north" is interpreted mythologically, cf. A. C. Welch, Jeremiah, His Time and His Work (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1928).

- Hyatt, Interpreter’s Bible, p. 787, lists 1:4-14, 17; 2:1-37; 3:1-5, 19-25; 4:1-8, 11-22, 27-31; 5:1-17, 20-31; 6:1-30 and possibly 8:4-9:1. Eissfeldt, op. cit., p. 351 selects the following: 1:2, 4-10, 11-17, (19) ; 3:6-13; 7:1-8:3; 11:(1), 6-14; 13:1-14; 16:1-13; 17:19-27; 18:1-12; 19:1-2; 10, 11a; 22:1-5; 25.

- William L. Holladay, "Jeremiah and Moses: Further Observations," Journal of Biblical Literature, LXXXV (1966), 17-27.

- J. M. Meyers, "The Book of Jeremiah," Old Testament Commentary, ed. H. C. Alleman and E. F. Flack (Philadelphia: The Muhlenberg Press, 1948), pp. 712f.

- E. Leslie, Jeremiah (New York: Abingdon Press, 1954), pp. 82 ff.

- C. H. Cornill, Das Buch Jeremia (Leipzig: B. Tauchnitz, 1905), p. 144; J. Skinner, Prophecy and Religion (Cambridge: University Press, 1955), pp. 102 ff. For a detailed analysis, cf. H. H. Rowley, "The Prophet Jeremiah and the Book of Deuteronomy" in Studies in Old Testament Prophecy (ed. H. H. Rowley) (Edinburgh: T & T Clark 1950), pp. 157-174.

- J. P. Hyatt, The Interpreter’s Bible, V, 906.

- Martin Buber, The Prophetic Faith (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1949), pp. 170 f. places this question in 609 after the death of Josiah.

- It should be noted that Jer. 3:1 is based on Deut. 24:1-4.

- In Egypt, during the twelfth or thirteenth dynasties, the execration of enemies involved the inscribing of names or places on bowls and smashing them. Cf. ANET pp. 328 f.

- Apparently Jeremiah’s advice was heeded and a colony of Jewish scholars remained in Babylon for over 1,000 years.

- Martin Buber, The Prophetic Faith, p. 182, points out that the sufferings of the prophet are symbolic of the suffering of the nation throughout its history.

Old Testament Life and Literature is copyright © 1968, 1997 by Gerald A. Larue. All rights reserved.

The electronic version is copyright © 1997 by Internet Infidels with the written permission of Gerald A. Larue.