(2023)

Man is a credulous animal, and must believe something; in the absence of good grounds for belief, he will be satisfied with bad ones.

— Bertrand Russell, “An Outline of Intellectual Rubbish” (1943)

In my critique of the Bigelow Institute for Consciousness Studies (BICS) essay competition on the “best” evidence for life after death and my response to the summer and winter commentaries on it, I made reference to striking similarities between the arguments made by Christian fundamentalists and survival researchers (i.e., those who purport to investigate survival of bodily death scientifically). In this essay I’ll highlight or elaborate on fifteen or so examples of how those at the forefront of “scientific” research into an afterlife—or in BICS’ framing, the survival of human consciousness after death—have consistently used fallacious arguments that mirror parallel arguments prominent among fundamentalist Christians.

Here I’ll only note instances of fallacious reasoning found among prominent survival proponents working within psychical research and parapsychology that have parallels with arguments that could be taken straight from the Christian apologetics playbook. Readers interested in their other fallacious arguments should consult my published articles linked in the first paragraph here, where I quoted verbatim such instances and (like here) bolded the names of the fallacies committed (rather than making unsupported accusations of fallacious reasoning, which anyone can do whether they are present in one’s opponents’ arguments or not).

I should note at the outset that I was not looking for such parallels when I began my critique, but felt compelled to point them out because I kept running into them. I think it is important for readers to be aware of them since they shatter the illusion promulgated by many survival proponents that they are engaging in research that adheres to scientific best practices. Note also that many passages commit multiple fallacies, and in such instances I might just name the most salient one.

1. Spinning Appeals to Contrary Evidence as Dogmatic Adherence to a Whatever-ist Agenda (It’s All Politics, Man!)

Critics of survival research, like critics of intelligent design creationism, are often accused of rigid adherence to scientism, reductionism, materialism/physicalism (“fundamaterialism“), pseudoskepticism, or some other rhetorically charged -ism in order to distract from the salient evidence that critics provide (whether it comes from neuroscience or evolutionary biology). In his first-place $500,000 prize-winning essay, for example, influential parapsychologist Jeffrey Mishlove has a section on “Scientism’s Dark Shadow” (pp. 10-13). Compare this to intelligent design creationist Denyse O’Leary or prominent Christian apologist J. P. Moreland.

Dogmatic commitment to “materialism” (rather than the argued-for pure mortalism that I defend) at all costs (rather than due to the fact that there is strong evidence that an idea is true) is said to be the driving force for doubting survival after death, paranormal phenomena, intelligent design, or what have you, because if a proponent frames the issue as their quasi-religion, then that proponent never has to talk about the evidence that their opponents offer for their conclusions. Instead, you can rile up your base (instead of addressing everyone) with rhetoric about the injustice of the materialist agenda:

It would be an interesting data dive to find out how many of those who publish in survival research also publish in the creationist literature since the fallacious arguments are largely the same. You can’t make this stuff up…

Throughout my 2022 exchanges with psychical researchers, I pointed out instances where survival researchers repeatedly attribute skepticism about life after death, almost without fail, to a “dogmatic adherence to a quasi-religious ‘physicalism'” (p. 804n4). As I noted in the exchange (and previously), I don’t even seek to defend materialism/physicalism in the first place, no matter how often psychical researchers attribute this position to me. I simply point out that our best evidence makes it highly likely that human consciousness requires a functioning brain, and therefore, in all probability, one’s individual consciousness ceases when one’s brain ceases to function. There is an argument here, and it is not at all hard to follow. It’s just easier to resist it by pretending that the argument was never made.

So I don’t even aim to defend materialism/physicalism. But even if I did, there’s an uncharitable assumption here that, for one’s opponents at least, the -ism comes first and the evidence presented is only offered in the service of defending it, come what may. But why assume the worst of those whose conclusions differ from your own? Don’t people often defend a certain point of view because the evidence suggests that it is true? Many -isms are simply shorthand for positions that have been scientifically established. One idea about the relationship between celestial bodies in our solar system has been dubbed heliocentrism, allowing us to label those who affirm that the Sun is the (near) center of the solar system heliocentrists. But just because we can put a label on them doesn’t indicate that they are married to the concept; rather, they accept it because what the label refers to is what the evidence strongly indicates is true. Another conceptual label, this one affirming that the primary drivers of the diversity of life on Earth are known natural processes, is “Darwinism.” Ideas suffixed with -ism aren’t thereby automatically rendered faith-based belief systems, dogmatically held or otherwise.

Similar points apply to the use of the term “worldview.” Those in international relations could be said to accept (and even promote!) a certain geopolitical worldview, for example, but that doesn’t mean that their points of view aren’t heavily informed by our best evidence about the state of the world. Given this undeniable reality, why not address the evidence and arguments offered for a point of view, rather than dismissing a point a view merely because a simplifying label can be put on it? Anyone can be accused, with or without justification, of rigidly holding a point of view. Such accusations are totally irrelevant red herrings when your opponents offer rational grounds for holding their views. Why not address those grounds, then? Deflecting the responsibility of doing so is just a red flag that one lacks good reason to reject an opponent’s position.

When tribalistic survival proponents talk about me (instead of to me), they often present variations of a similar fallacious argument that runs something like this: ‘If even one near-death experience (NDE) demonstrated veridical paranormal perception, Augustine’s position would be refuted. Therefore he will always deny that any instances of veridical paranormal perception have been demonstrated.’ The first sentence expresses a true conditional statement—emphasis on “if.” The second sentence conjectures, on no grounds whatsoever, that the hypothesis that I defend in light of what we know now is a hypothesis that I am (for some unfathomable reason) wedded to until the end of time. Here’s a real-world example:

Inaccurate conjectures about my “manner of perceiving” aside, changing the subject from how to answer my arguments to the most rhetorically convenient speculation about my psychological needs is clearly an ad hominem fallacy. To keep things simple, consider my hypothetical example. It’s true that all that it would take is one “white crow” to overturn my evidence-based stance on veridical paranormal perception during NDEs (or perhaps discarnate personal survival more generally). But rather than undermining it, that fact supports my position on the issue. Why? Because conditional statements concern in principle truths about hypothetical scenarios (hence the “if”). They tell us nothing about what has actually been found to be the case in practice. Thus we need more than simply one claimed white crow—we need a scientifically verified white crow. And whether or not we have the latter is not up to me to decide in the first place, but up to the scientific community as a whole. This makes uncharitable speculations about my psychological needs entirely irrelevant (and I’m quite capable of changing my mind about any number of issues so long as I’m presented with good grounds to rethink them, thank you very much). The fact that survival researchers cannot point to any scientifically established white crows on this issue, despite the fact that such instances are perfectly conceivable, is what supports my position. And that fact has nothing to do with features of my psychology. Indeed, it has nothing to do with me at all. Rather, it concerns the state of the survival evidence, whose features are what they are completely independently of my views or my (or anyone else’s) willingness to acknowledge those features.

To see that this is poor reasoning, one need only consider the ridiculous parallel argument that would result from the beginnings: ‘If even one authentic satellite video showed the Earth as a flat disk, Augustine’s round-Earthism would be refuted.’ Indeed—but so what? Can you actually produce such evidence, or not? (To say nothing of the authenticated evidence that shows the opposite, which an honest evidential assessment would also have to admit into evidence.) Had the BICS contestants actually met their directive to provide evidence “beyond a reasonable doubt” of the discarnate survival of individual human consciousness after death, nothing that I might have to say on the matter would be material. That the BICS contestants did not do this is evident from the simple fact that geographers have come to a consensus that the Earth is round, but the BICS contestants’ “evidence” did not result in a consensus among psychologists or other cognitive scientists that human consciousness survives death. Albert Einstein’s “annus mirabilis” papers produced a revolution in physics. The BICS contest produced nothing even close to that for the scientific study of the mind. And the difference in their respective impacts had nothing to do with me or any other skeptics. The BICS contestants simply did not deliver the goods because there were no goods available to them to deliver. As I wrote in my reply to Braude and co.: “The issue was never about what any particular person believes, but about how discarnate personal survival could move from an item of personal belief to an item of scientific knowledge” (p. 422).

2. Changing the Subject to Critics’ Motivations

As I point out in an endnote, survival researchers like prominent parapsychologist Stephen Braude often use stigmatizing red herrings to change the subject from the real crux of the issue—the state of the survival evidence—to the immaterial issue of “the psychological disposition of any particular person or tribe” (p. 422):

Ironically, in the same paragraph where Braude et al. accuse me of committing the same fallacies that I extracted verbatim from the BICS essays—which is itself an ad hominem tu quoque [“you do it, too!”] if there ever was one—they add: “Augustine seems to infer not simply that nothing psychic was happening during the tests of OBErs and NDErs [out-of-body and near-death experiencers], but more likely, given his broad skepticism about things paranormal, that nothing psychic could occur.” That’s an odd thing to say of tests that, as a contingent matter of fact, have historically failed to reveal any evidence of psi [i.e., the paranormal]. Apart from an aversion to the principle of charity, what prompts this attribution—the fact that other skeptics have expressed this? (e.g., Alcock & Reber, 2019). The reason why “Augustine never clarifies this” is because it exists in their heads, not in my BICS critique. (p. 432n17)

As I noted in the main text, the issue was never about any particular person’s motivations; rather, the issue was “whether or not survival researchers have delivered the kind of evidence that would give the scientific community reason to think that there is something in this research in need of novel kinds of explanation. What scientific conclusions does the evidence warrant?” (p. 422) If the evidence on offer really could withstand scientific scrutiny, why change the subject?

Similarly, in his winter commentary, biologist Michael Nahm wrote: “Regarding Augustine, I perfectly agree with Braude et al. (2022) and previous critics of his work who already demonstrated earlier that his manner of arguing is selective and biased indeed” (p. 787). Of course, anyone can claim—or simply repeat/cite the unsupported claims of others—that an opponent is “biased” for merely defending an alternative position. Are those who say that the Earth is round (an oblate spheroid) “biased” since they take a position on the issue of the Earth’s shape? Are those who take the opposite position somehow magically unbiased, despite having a position to defend themselves, and a stake in maintaining their position? On the playground one might expect opponents to fall back on childish discreditation or lazy generic accusations of bias (that anyone with a different view could be accused of for having—gasp!—provided arguments for their views), but it is unbefitting of scientific debates about evidence.

Do proponents really believe that researchers who’ve devoted the bulk of their research careers to trying to vindicate the existence of life after death are equally open to the possibility that maybe, quite possibly, there is no afterlife? Their reputations are no less tied to their long-held positions than those of skeptics—and arguably more so since skeptics tend to not to have decades-long careers whose sole purpose is to find evidence for a particular point of view on a single issue. In this respect it’s notable that survival researchers are often inducted into psychical research societies, but there are no “extinction researchers” inducted into neuroscientific research societies surrounding them.

Moreover, there’s a distinction between arguing for a position because your career requires you to do so and defending a position (within one’s career or otherwise) because one believes that it is true on the basis of evidence that can be clearly spelled out and argued, making accusations of bias all the more irrelevant. Why automatically assume the worse motivation when someone provides reasons for views that you happen to disagree with (but under different circumstances, or in the future, might come to agree with)? Why not tell readers why the cited reasons are wrong, instead of killing the messenger?

There are those who research the mind’s relationship to a functioning brain, of course, in cognitive neuroscience and philosophy of mind with no particular professional interest in the survival of human consciousness after death, so one might anticipate that their (particularly consensus) conclusions ought have more weight (prima facie) than the conclusions of those triggered to explicitly resist certain conclusions whenever they fail to serve making a case in favor of survival after death. In this sense the relationship of survival research to cognitive neuroscience or the philosophy of mind is akin to the relationship between “creation research” and evolutionary biology or the philosophy of biology.

How many Christian apologists speculate about the depraved motives of atheists who purportedly deny God’s existence in order to excuse their immorality or sexual deviancy, rather than address atheists’ arguments?

3. Different Perspectives Spun as Rationalizations for Immoral Behavior

In my opening BICS critique, I noted how out-of-body experience (OBE) researcher and parapsychologist Charles Tart proposed that materialists would ask “Why bother?” if confronted by a drowning child, parapsychologist Dean Radin and coauthors claimed in their BICS essay that acknowledging that we finite creatures might not exist for all eternity “leads to exaggerations of the worst vices of humanity: envy, greed, and selfishness,” and so on. These fallacious arguments from consequences are ubiquitous among creationists and Christian apologists. Compare Larry Arnhart‘s reporting in the old Salon article “Assault on Evolution: The Religious Right Takes its Best Scientific Shot at Darwin with ‘Intelligent Design’ Theory” (February 28, 2001):

At the [three-hour] briefing [with the US Congress], Nancy Pearcey quoted the lyrics of a song by the Bloodhound Gang—”You and me, baby, ain’t nothin’ but mammals, so let’s do it like they do it on the Discovery Channel.” This, she warned, is what we can expect if the materialism of the Darwinians persuades us that we are merely mammals, rather than beings elevated above other animals and created in the image of God. She urged the congressmen in her audience to remember that the US legal system is grounded in the belief in a creator as the ultimate source of moral law. Darwinism, by undermining that belief, is morally and legally dangerous.

A verbatim quote of the late creationist Henry Morris making parallel fallacious arguments is provided in the critique itself. And within Christian apologetics that is not specifically creationist, how often do we encounter tropes about how Adolf Hitler was an atheist (untrue) or that Joseph Stalin was an atheist (true but irrelevant)?

4. You’re Suppressing My Beliefs if You Don’t Promote Them!

Unsatisfied with simply characterizing “materialism” as a “nihilistic philosophy,” Radin and co. go on to add:

The cynical quip, “He who dies with the most toys, wins,” captures the harmful effects of absorbing a picture of reality that children begin to learn as soon as they enter the (secular) educational system, and that is inculcated in adults for the rest of their lives.

But as I point out in my opening critique, refraining from inculcating otherworldly beliefs is not the equivalent of inculcating anti-otherworldly beliefs. Rather, it is neutrality or respect for tolerating the diversity of individual opinions on issues that have not been scientifically established. Failing to promote your view is not equivalent to promoting others’ views, period. This fallacious argument is nothing new, of course:

5. Coloring Morally Neutral Concepts with Immoral Aspects

Under the previous heading, we’ve just seen Radin and co.’s conflation of materialism, sometimes defined as the view that everything is physical (which one need not even affirm to doubt life after death), with materialistic consumerism. In my opening BICS critique, I mentioned in passing how OBE researcher and parapsychologist Charles Tart did the same thing in his The End of Materialism: How Evidence of the Paranormal is Bringing Science and Spirit Together. In his characterization of the supposed consequences of accepting “scientistic materialism” as true, Tart writes:

Long-term, I really needn’t worry about the degradation of the planet, global warming, overpopulation, and so on…. I’ll likely be dead when civilization collapses. So I’ll use resources to make myself happy now and not worry about the distant future. If I feel any guilt about this or worry about my descendants, that’s meaningless social conditioning and biological built-ins manifesting: I should ignore them and get on with looking out for number one. (2009, pp. 299-300)

Recall Arnhart’s paraphrase of Nancy Pearcey a few headings above that the biological theory of evolution by natural selection “is morally and legally dangerous,” as if this consequence—even if it were true—would have any bearing on the truths of biology.

6. It’s Depressing, Therefore It’s False

In my opening critique I quoted Dean Radin and co. stating: “Materialism tells us that there is no purpose to anything. When we die, we are forever extinguished, and our atoms are recycled into other purposeless creatures. Eventually, all the suns will burn out, the universe will grow cold, and by a random fluke, the whole meaningless cycle might begin again” (p. 33). What relevance does this true statement have to whether or not survival researchers are able to provide strong evidence for the existence of an afterlife? Does this appeal to emotion sound familiar?

Like psychical researchers leaning on the same trope, in his opening statement in the Lowder-Fernandes debate above, Christian apologist Phil Fernandes seems to confuse the depressing with the meaningless. Of course, anyone who has lived long enough will recognize that life contains both uplifting and depressing aspects—c’est la vie. But this fact doesn’t automatically render life meaningless. And no doubt some human beings experience the negative aspects of life far more often than the positive ones, opening the possibility that some (but not all) lives are not worth living. For the most part, I would venture to guess, those living in the West since the advent of modern medicine are comparably Pollyannaish, for they often have little inkling of the hardships that those in other parts of the world, or those in earlier times, had to face. Anyway, Fernandes goes on to quote Bertrand Russell:

That Man is the product of causes which had no prevision of the end they were achieving; that his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and his beliefs, are but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms; that no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling, can preserve an individual life beyond the grave; that all the labours of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and that the whole temple of Man’s achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the debris of a universe in ruins—all these things, if not quite beyond dispute, are yet so nearly certain, that no philosophy which rejects them can hope to stand. Only within the scaffolding of these truths, only on the firm foundation of unyielding despair, can the soul’s habitation henceforth be safely built. (“A Free Man’s Worship,” 1903)

Of course, all of this is terribly useful for getting an audience to reject an idea for reasons other than rational ones. But those leaning on either Christian or survivalist apologetics don’t put Russell’s quotation in the context of other things that Russell wrote, such as:

I believe that when I die I shall rot, and nothing of my ego will survive…. But I should scorn to shiver with terror at the thought of annihilation. Happiness is [no less] true happiness because it must come to an end, nor do thought and love lose their value because they are not everlasting. (“What I Believe,” 1925)

Indeed, philosopher Wendell O’Brien puts Russell’s more famous (or infamous) quotation in its true context over at the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy in the entry on “The Meaning of Life: Early Continental and Analytic Perspectives.”

Yes, it’s highly likely that you won’t get to live forever and ever and ever (sorry!), and that nothing that you do now will matter in a million years. (By the same token, nothing that happens in a million years should matter to you now, either.) Pretty much everything that we do is fleeting, but no less meaningful because of it. The worthwhileness of a thing does not depend on it lasting forever, pure and simple. Relationships typically end, but that fact does not mean that they were not worthwhile while they lasted. Indeed, innumerable songs often look back at past relationships with nostalgia precisely because they were worthwhile at the time. Children build sandcastles knowing that the tide will wash them away, or snowmen that they know will eventually melt, because they find the activity of building something valuable worthwhile. Concerts don’t last forever, but are no less worthwhile merely due to their transience.

If a person’s life overall is full of personally meaningful activities, one should be grateful for the time that one was gifted (and one’s luck at being so fortunate)—even if one doesn’t have forever. A life doesn’t have to last forever to be worthwhile. A good life will remain good even if “it must come to an end.” That most of us mourn the loss of life betrays that we believe, on some basic level, that life is often good. Otherwise we would welcome death as a release from the burden of existence. To the extent that life is worthwhile, death is bad (since it ends a worthwhile thing); and to the extent that life is bad, death is good (since it ends a thing that isn’t worthwhile). The late philosopher Jacques Choron relates a joke that captures this point nicely: “Thus, the pessimist reminds one of the joke where a man, asked about the food in a restaurant, replied that it was very bad, but that, moreover, the portions were too small” (Death and Modern Man, 1973, p. 165).

7. Loosening Standards for One’s Own Beliefs (Moving the Goalposts)

In my initial BICS critique I also point out that Braude’s position that there is “a rational basis for belief” in discarnate personal survival falls far short of the evidence “beyond a reasonable doubt” that he was tasked with providing:

Are we rationally permitted to believe in personal survival? (Braude, 2021*, p. 1). Sure. As Alvin Plantinga has famously argued, we might well be rationally permitted to accept the religious belief system instilled in us in childhood in the absence of evidence, and even have no compunction to ever review the available (historical) evidence relevant to its truth or falsehood even when that could help settle the question for us (2000, pp. 416-417, 420-421). If what rationality permits is the bar, it’s a rather low bar. (p. 390)

8. Double Standards (Special Pleading)

In my initial critique, I also asked what justified Nahm “raising the bar for neuroscientific evidence while lowering it for evidence from psychical research?” (p. 391n7). For in his BICS essay, Nahm had written that “it is principally impossible to prove that brain chemistry produces consciousness—all we can observe are ‘concomitant variations’ of brain states and states of consciousness.” I pointed out that, while this is logically true (as it is for any piece of scientific evidence), nevertheless such concomitant variations constitute evidence against discarnate personal survival. By contrast, Nahm had written of the evidence from psychical research, “we usually don’t speak of ‘proof’ in sciences like psychical research.” While he acknowledges a less-than-mathematical sense of “proof” when discussing the evidence from psychical research, he makes no such distinction when discussing the evidence from neuroscience. Nahm later challenges me that he is raising the bar for one but not the other, but I back up my point in my response to his first misrepresentation allegation in my reply to Nahm’s winter commentary (pp. 798-799).

How many Christian apologists appeal to inherently weaker historical evidence for the resurrection of Jesus while dismissing stronger biological evidence that species have evolved over time?

9. Ad Populum

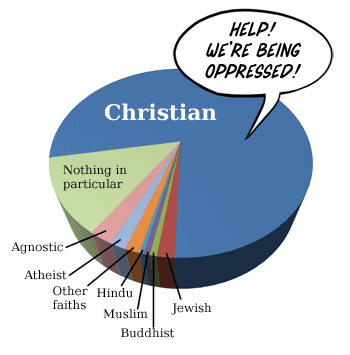

Like many poor reasoners, Mishlove seems to regard the widespread popularity of a belief across times and places as some sort of reason to think that that belief is true, spurring him to write: “A belief in postmortem survival of consciousness is common to every culture, nationality, religion, and linguistic group in every region and historical period on Earth. Every single one!” As Mark Twain points out, the same was true of belief in a flat Earth 2,000 years ago, with science having corrected our intuitions since. While the popularity of a belief is not a good reason to think that it is true, nevertheless similar arguments have been made about the existence of God, and stigmatized those who dare deviate from popular opinion, as dramatized in this fictionalized conversation:

10. Possibly, Therefore Probably

If a standard probabilistic assessment (any such assessment) would render one’s pet theories highly unlikely, those who arbitrarily make up their own rules of logic can always change the subject. When there is no way to show exactly where an opponent’s evidential assessment goes wrong—since it doesn’t go wrong—one can always evade the point by arguing as if the opponent was talking about what’s possible instead of what’s likely. Commenting on how the psychic abilities of skeptical observers might suppress any display of paranormal abilities, Braude and co. write:

We have no reason to think that people will be so well-behaved in exercising their psychic abilities, and we also have no idea what issues or hidden agendas might be on the minds of participants and onlookers, perhaps motivating them to [psychically] influence the results of the tests [to fail to produce any evidence of psychic abilities]. (p. 405)

No doubt, such a scenario is logically possible. But those familiar with the philosophy of religion might recognize that theistic versions of this argument were refuted over 30 years ago by agnostic philosopher Paul Draper:

Of course, an omnipotent and omniscient being [who is perfectly good] might, for all we know antecedently, have moral reasons unknown to us to permit the evil reported by [observation] O. But it is also the case that such a being might, for all we know antecedently, have moral reasons unknown to us to prevent this evil. So human ignorance does not solve the theist’s evidential problems. (Draper, 1989, pp. 345-346)

Draper’s point is that whatever reasons we can guess for why a morally perfect being might allow apparently gratuitous evils, we can guess with equal justification (i.e., none) that he might have had completely different reasons incompatible with the existence of the evils that we observe. Thus the observed evils constitute evidence against the existence of an all-powerful, all-knowing, and perfectly good God to the extent that, on the face of it, we would not expect to find such evils if a being meeting the definition of those characteristics existed. In my reply to Braude and co., I write:

Braude et al. would have us take seriously the bare possibility that the psi of the hypothesized discarnates might be exactly counterbalanced by the counter-psi of mediums or skeptical experimenters (or any other living persons, near or far, as single individuals or in combination), producing a net zero “amount” of psi displayed. This bare possibility duly noted, if no psi effect is found in a particular test, then we can reasonably presume that no psi was present in it. (p. 420)

As I elaborate in endnote 14, “just as the bare possibility of greater overriding consequent goods is balanced out (or neutralized) by the equally bare possibility of even worse consequent evils, the bare possibility of counter-psi is balanced out (or neutralized) by the equally bare possibility of reinforcing psi doubling rather than neutralizing a displayed psi effect.” In the absence of a refutation of Draper’s specific point, then, we can only cross our fingers that psychical researchers will omit this appeal to possibility from their talking points in the future.

How many instances of Christian apologists committing the same “possibly, therefore probably” fallacy can you think of?

11. Guilt by Association Ad Hominem and Genetic Fallacy

In his BICS essay Nahm repeatedly characterizes criticisms of reincarnation research found among both skeptics and proponents of psychical research as the objections of (no doubt inherently untrustworthy) skeptics (which, therefore, evidently discredit themselves). For example, there’s no question that Paul Edwards‘ 1996 Reincarnation: A Critical Examination took an unproductively mocking tone in several places, in addition to “assembl[ing] practically all relevant criticism of CORT [cases of the reincarnation type] offered up until 1996…. originally advanced by parapsychologists and concern[ing] Stevenson’s writings up until the early 1970s” (Nahm, p. 38; emphasis mine). Later, Nahm points out that “Edwards makes it clear on the first page of his Introduction that it is his goal to show that the claimed evidence for reincarnation is ‘worthless'” (p. 38). “Still,” we’re informed, “Edwards has several followers. Among them are Michael Murray and Michael Rea, who wholeheartedly recommended Edwards’ ridicule of reincarnation research in 2008 and relied almost exclusively on it” (p. 39). We’re told that this results in theistic philosophers Murray and Rea “presenting a grossly deficient overview of Stevenson’s work” (p. 39), further leading to “Keith Augustine approvingly cit[ing] Murray and Rea’s distorted critique in 2015 when he recapitulated Edwards’ arguments in his Introduction to a thick book entitled The Myth of an Afterlife” (p. 39). It’s notable here that I merely cited two points from their allegedly “distorted critique”—namely, that children seem to have rather undeveloped minds if they were once adults, and that some putative reincarnation cases might lack confirmed alternative normal explanations merely due to the absence of enough information to identify them. But with the backward chain from Augustine to Murray & Rea to “Edwards’ emotionally-tainted ridicule of CORT research” (p. 45) put forward, however weakly, Nahm can then simplify to “Edwards and Augustine’s argument” (p. 46) or “the conjecture of Edwards, Augustine, or Murray and Rea” (p. 57), having conveniently forgotten that the chain began with criticisms “originally advanced by parapsychologists”! What matters, of course, is not who voiced a criticism, but whether a criticism is valid or not—and at one point Nahm even concedes the validity of most of the criticisms under discussion, making his guilt by association ad hominem doubly pointless.

Attributing the characteristics of the most derisive skeptics to other skeptics simply because both are doubtful that a particular position is true is hardly different than stereotyping your run-of-the-mill atheist based on the murderous behavior of ruthless atheists.

Nahm did take issue with what he perceives that I “insinuated,” namely that “Stevenson performed very little research after the early 1970s” (p. 39). The fact that I never said any such thing is immaterial when the goal is to discredit one’s target. Nahm evidently believes that by publishing a summary of one of Stevenson’s research assistant’s criticisms that dates back to late 1972, I thereby “insinuated” that Stevenson conducted little research since then. In truth, I never insinuated anything about how much reincarnation research Stevenson did since the 1970s one way or the other. Of course, if you’re looking for just about anything to criticize simply for the sake having a criticism, a straw man will do. But Nahm was also aware of why I included this contribution from my explanation on this point back in 2016 in my reply to an off-the-mark book review:

The oldest of these selections warrants further comment here. The original Ransom report detailed 18 methodological problems with the late Ian Stevenson’s reincarnation research, 13 of which were noted in the abbreviated summary of the report published in the volume. The remaining 13 items address problems inherent in the testimonial nature of the evidence that Stevenson collected, which means that they are of the sort that cannot be eliminated, or cannot be eliminated very easily. Thus they are just as relevant today as they were in 1972. Since no other contribution explores the inherent weaknesses of the sort of testimonial evidence that survival research relies upon so heavily, the original Ransom report seemed a good fit for the volume. Although some of the items in the original report may be dated, they would have been offset by the inclusion of both Stevenson’s reply to the report and Ransom’s response to it, had Ransom and I been able to secure permission from the Division of Perceptual Studies to publish the entire exchange. (2016, p. 205)

Nahm best explains the other thing that he took issue with, which he calls “Edwards and Augustine’s argument” (p. 46):

One of the reasons that led Edwards, Augustine, and others to believe that Stevenson was misguided when interpreting his field studies in foreign counties was that he usually entered the scene as a stranger without deeper insights into the local conditions and that he had to rely on local researchers and interpreters in his interviews—for example, Satwant Pasricha. Because she is Indian and believes in reincarnation, Edwards considered her and other local assistants who believed in reincarnation and participated in CORT investigations principally unqualified to participate in these studies.

Nahm’s “unqualified” seems exaggerated here, but apart from that, merely mentioning a criticism found in the literature in a survey of the literature is hardly an indictment of anything, which is perhaps why fellow survival researcher Braude noted the exact same criticism in his BICS essay, as I noted in endnote 8 of my reply to Nahm:

Somehow Braude’s legitimate concern that “many cases also require the services of translators whose own biases, inadequacies, and needs might influence the direction or accuracy of the testimony obtained” (Braude, 2021*, p. 32), originally raised by prolific paranormal author Ian Wilson (1982, p. 50), becomes transformed into “Edwards and Augustine’s argument” (Nahm, 2021*, p. 46) or “the conjecture of Edwards, Augustine, or Murray and Rea” (Nahm, 2021*, p. 57) in Nahm’s guilt by association ad hominem. Even if the skeptical literature contains “a disconcerting amount of scorn, sweeping generalizations, and misinformation,” that’s not an indictment of anything that I have written.

In any case, my reply to Nahm’s commentary (and earlier exchange with Braude and co.) presents, among other things, an altogether different criticism of reincarnation researchers—namely, that they have not met their burden to show that the reincarnation hypothesis best explains cases of the reincarnation type (CORT), or merely makes reincarnation more probable than not—let alone demonstrated reincarnation “beyond a reasonable doubt,” as BICS mandated. All that Nahm does is repeatedly shift the burden of proof off of his own case for reincarnation and on to skeptics to make a case that CORT are best explained by non-reincarnation. But why should someone who is unconvinced of your assertions (in place of a case for your position) have to do anything at all? Nahm is the one claiming to have shown reincarnation beyond a reasonable doubt! So where is Nahm’s argument—his premises, recognized logical form, and derivations from combining those premises—that accomplishes that feat? Nothing has been offered to refute.

12. Shifting the Burden of Proof Off of One’s Own Positive Existential Claims

In my original BICS critique I didn’t have the space to do more than mention two instances where psychical researchers shift the burden of proof off of themselves and on to those who are simply unconvinced of their claims—namely, in their failure to establish that electronic voice phenomena represent more than pareidolia (p. 383) and in Nahm’s use of loaded terms (p. 393n19) to favor his position without actually arguing in its favor. Fortunately, Nahm felt compelled to offer a separate commentary on the summer exchange, opening the door for me to expand upon his frequent deployment of this fallacy.

While I could quote my response to Nahm’s commentary, instead I’ll keep the point brief since an entire section of my reply is devoted to examples of Nahm shifting the burden of proof on to anyone who merely refrains from affirming his conclusions. There’s a tendency for reincarnation researchers like Nahm, and psychical researchers in general, to offer certain (ostensible) facts as if they are evidence for reincarnation (or discarnate personal survival in general). However, they rarely even outline how these putative facts would lend evidential support to these hypotheses. At a minimum, such researchers should tell us why these putative facts would be more expected were reincarnation true rather than were it false. This they rarely (if ever) do, making it impossible to assess their case—which is just to say that they don’t actually provide any evidential case to evaluate. There are plenty of ways to show that a particular piece of evidence constitutes evidence for a hypothesis, as exemplified by my coauthored “The Dualist’s Dilemma: The High Cost of Reconciling Neuroscience with a Soul” (2015), or Michael Sudduth’s groundbreaking A Philosophical Critique of Empirical Arguments for Postmortem Survival (2016).

Some shift the burden of proof in subtle ways by redirecting attention to secondary but related issues. A common apologetic tactic, for example, presses how to best explain why Jesus’ tomb was empty (if not due to his bodily resurrection) while ignoring or blithely dismissing the more central question of what reason we have to believe that an empty tomb ever existed in the first place.

13. Straw Man

As I already noted in earlier items #1 and #11, a tactic common in both Christian and survivalist apologetics is to attack a caricature of one’s opponents’ views rather than the views themselves. In Nahm’s winter commentary, for instance, I’m erroneously characterized as “a physicalist who maintains not only that mind is positively caused by brain activity but who additionally advocates the peculiar stance according to which all mental processes are brain processes and that the mind is the nervous system” (p. 788). This allows Nahm to (attempt to) refute faux Augustine by proposing from this straw man “deductions [that] are consequential” about “causally closed brains” (p. 790) and the like, while simultaneously making plain his ignorance of the topic of discussion (which I will address in a later item). But as philosopher David Kyle Johnson points out when addressing Christian apologists in Philosophia Christi, a person can deny “that our minds are housed in a separable substance (called a soul) that can float away from our body when we die” without, contra a common apologetic argument, rejecting that either mental processes (1) exist or (2) cause our behavior (Johnson, 2018, p. 543). The latter claims are attempts to straw man those who don’t believe in souls. As Johnson notes, all that it takes to do this is to affirm (or merely consider as possible) any theory of mind in the philosophy of mind other than eliminative materialism/illusionism (which says that conscious experiences do not exist) or epiphenomenalism (which says that conscious experiences, while they exist, do not affect the physical world in any way). In Johnson’s words: “to the extent that readers recognize either Russellian monism, property dualism, or identity theory as a naturalist theory that holds the mental to be causally operative on the basic level, the debate is over” (p. 546). Indeed, I take Johnson’s point even further in the penultimate section of my initial BICS critique (“The Mind-Body Problem, Botched”—p. 384ff). One can even affirm that nonphysical souls exist (interactionist substance dualism), or that nothing physical exists (idealism), and still have strong empirical evidence that an individual’s conscious mental processes cannot exist/occur absent a functioning brain, which thereby blocks the scientific tenability of discarnate personal survival after death. I’m forced to repeat the point in endnote 4 (p. 804n4) of my response to Nahm’s winter commentary because too many survival researchers are unwilling to give up a talking point as rhetorically useful as “It’s all just fundamaterialism, man!”—whether this claim is true or not.

14. Arguments from Revelation

Although he is vague about the details, in his winter commentary Nahm ultimately resorts to a personal argument from revelation:

In my life, I have had a number of experiences that I can solely explain in terms of psi, and I also had one time-anchored experience of dual awareness that I can only explain in terms of the supposition that one part of my mind operated independently of my brain—even though I am perfectly aware of all the evidence for the “dependence thesis,” the dangers of misinterpreting such experiences, etc. In each case, these experiences were very plain and simple—not of the kinds that are complex and difficult to interpret, such as alien abductions or fleeting apparitions in twilight. I also know that countless people, ranging from intimate family members and friends to strangers, have reported very similar experiences…. Therefore, reading theoretical treatises by people who insist that the experiences I had are “impossible” (Reber & Alcock, 2019) or that my interpretations of them must be wrong is often perplexing and sometimes even amusing; and pretty much the same applies to theoretical elaborations in which authors explicate how proper “probabilities” for the mind/brain-dependence must be gauged (Augustine, 2022a, 2022b; Augustine & Fishman, 2015; see also Nahm, 2021, p. 59). I know that I speak for very many people including scientists when I say: For those who have solid first-hand experiences demonstrating the contrary, such authors are simply not on a level playing field. They do not know what they are talking about. (p. 790)

I can only surmise that Nahm’s point is that, for him, his personal experiences (whether correctly interpreted or not, or remembered accurately or not) will always trump any assessment of publicly available evidence by anyone. And that’s fair enough. Among the chosen people who’ve been privy to such revelations (divine or otherwise), I think that this is a reasonable position to take, though I would (personally) be wary of reading much more than “maybe” into a purely subjective experience that cannot be verified by others in some way. But as I point out in my response to Nahm, “It’s odd for Nahm to voluntarily enter projects to convince others of his views using evidence” with this attitude (p. 806n21). The problem is that while such experiences might be evidence for the person who undergoes them, they don’t do much for the rest of us:

But admitting, for the sake of a case, that something has been revealed to a certain person, and not revealed to any other person, it is revelation to that person only. When he tells it to a second person, a second to a third, a third to a fourth, and so on, it ceases to be a revelation to all those persons. It is revelation to the first person only, and hearsay to every other, and, consequently, they are not obliged to believe it.

It is a contradiction in terms and ideas to call anything a revelation that comes to us at second hand, either verbally or in writing. Revelation is necessarily limited to the first communication. After this, it is only an account of something which that person says was a revelation made to him; and though he may find himself obliged to believe it, it cannot be incumbent on me to believe it in the same manner; for it was not a revelation made to me, and I have only his word for it that it was made to him. (Paine, 1794/2010, p. 21)

Although Founding Father Thomas Paine was addressing the argument from personal revelations “recorded” in sacred texts like the Christian Bible, the principle is the same: your private experiences are not public evidence available to me (or anyone else not among the chosen), making them irrelevant to debates about publicly available evidence—debates that have rules of engagement, and debates that Nahm has entered of his own accord. Moreover, in my earlier reply to Braude and co., I had already asked (not unreasonably) why such experiences—particularly those that in principle could be publicly verified—nevertheless consistently evade such verification, over and over again. Those in parapsychological circles often appeal to the concept of “trickster phenomena“—to which New York Post reporter Steven Greenstreet incredulously responded, “So, we’re dealing with Loki?!”—but this is a rather convenient out from answering the question. It’s akin to acknowledging the logical possibility that the toys come to life at night when no one is looking (or recording), but that we also have no positive reason to believe actually happens. Nahm does not take up this earlier question, which seems to me to be a more salient one for a debate about public evidence. Moreover, since BICS’ directive explicitly called for a high legal standard of evidence, “proof beyond a reasonable doubt,” I pointed out:

Surely even Nahm is unpersuaded of the occurrence of some events that others seemingly of good character swear up and down to having witnessed first-hand. There’s good reason, for example, why the testimonial “spectral evidence” propping up the Salem witch trials is no longer admissible in a court of law. (p. 806n21)

Whether the claims at issue concern first-hand reports of paranormal levitations or textual accounts of divinely parted seas, the parallels are obvious. The “evidence”—insofar as it is provided in order to convince others of one’s ideas—is no evidence at all.

15. Mere Assertions

While Nahm may be satisfied with merely assuming without argument that we obviously have free will, the fact that this issue has been debated for millennia suggests that the answer to the question is anything but obvious. Interlocutors might therefore be reasonably expected to at least look into the issue before speaking on it, in order that they might be able to present some semblance of a reason for others to accept their views on the matter. Otherwise, speak only if it improves upon the silence:

[F]rom the perspective of the physicalists’ “world of natural science in all its mechanistic glory,” we are causally closed entities consisting of only “flesh, blood, atoms, and molecules” (Reber & Alcock, 2019, p. 10), or using Augustine’s more refined words: Mental processes are actually brain processes. It follows logically that there is no free will and that 1) we never had any chance to act differently than how we acted in the past and that 2) our futures are likewise fixed already except for quantum events we cannot influence (Hossenfelder, 2022; Vollmer, 2017). These deductions are consequential. Thus, I often marvel at physicalist skeptics who constantly treat parapsychologists and survival researchers as if they had a free will, blaming them of having performed pseudoscience, cherry-picking, and other “inexcusable” misconduct, complaining they should have known better, behaved differently, and thought more rationally—as if the molecules constituting their deterministically operating brain matter ever had the slightest choice of having processed the physicochemical stimuli they received in any other way—and especially: more “rationally”! According to physicalist logic, causally closed brains cannot behave differently than they do. Hence, the mental by-products of survival researchers’ deterministic brain processes just cannot be blamed for anything. Mind your accusations, please! But after all, the mental accessories of physicalists’ brains can also not be blamed for what they had to write and for what they will have to write—this may alleviate brooding about the reasons underpinning such unheeding paradoxical reasoning and systematic misrepresentations of other people’s work. Say what you will: Physicalism is an astonishing world view. In all its mechanistic glory. (Nahm, p. 790)

For starters, Nahm’s (1) and (2) are entailed by determinism, not physicalism, and physicalists need not be determinists. More importantly, though, merely rejecting determinism doesn’t secure us the existence of (traditional/libertarian) free will (for reasons apart from the truism that whether or not we have a certain capacity does not depend upon what anyone believes about that issue). As I point out in the last endnote of my reply to Nahm’s commentary:

If you have a reason for acting, then that reason caused (determined) your act. Under determinism, whether the causes of acts are entirely physical, both physical and mental, or entirely mental makes no difference so long as the acts are caused. Any act that happened because of its cause was determined by it—”because he made me mad” is no less causal than “because my aggression neurons fired”—and so out of one’s control. If any of one’s acts happened uncaused, on the other hand, then they happened for no reason whatsoever since nothing caused them to happen, and they are no less out of one’s control. Uncaused acts that happen to me are no more in my control than fixed caused acts “since I have nothing to do with them” (Taylor, 1974, p. 47). So if Nahm’s (2) is true, it’s true for everyone (physicalist or otherwise). (p. 807n23)

Control over which action one performs has traditionally been understood as a prerequisite for possessing free will (and for being morally responsible for one’s actions). The point about our inability to control our determined (i.e., caused) actions is put well by the French Enlightenment philosopher Baron d’Holbach, who notes that a man is “born without his consent; his organization does in nowise depend upon himself; his ideas come to him involuntarily; his habits are in the power of those who cause him to contract them; he is unceasingly modified by causes … over which he has no control which … determine his manner of acting” (The System of Nature, 1770, trans. H. D. Robinson, Vol. 1, p. 98). The details elucidating this point have been elaborated elsewhere many times over, so I won’t dwell on them here.

The point about our inability to control any undetermined (i.e., uncaused) actions that we perform, should there be any—the only logically possible alternative to determined/caused actions—is well argued by the late ‘Amish‘ philosopher Richard Taylor:

Suppose that my right arm is free, according to this conception; that is, its motions are uncaused. It moves this way and that from time to time, but nothing causes these motions…. Manifestly I have nothing to do with them at all; they just happen, and neither I nor anyone can ever tell what this arm will be doing next. It might cease a club and lay it on the head of the nearest bystander, no less to my astonishment than his. There will never be any point in asking why these motions occur … for under the conditions assumed there is no explanation. They just happen, from no causes at all…. [S]o far as the motions of my body or its parts are entirely uncaused, such motions cannot even be ascribed to me as my behavior in the first place, since I have nothing to do with them…. I can have no more … control over the uncaused motions of my limbs than a gambler has over the motions of an honest roulette wheel. (Metaphysics, 1974, 2nd ed., p. 47)

It’s doubtful that I ever actually perform any uncaused actions, but let’s assume for the sake of argument that I do. Conceptually, any actions that I perform that are uncaused simply happen to me, and so are no more in my control than fixed caused acts since, as Taylor put it, “I have nothing to do with them.” But then undetermined/uncaused actions are no more “free” (that is, within my control) than determined/caused ones, leading to this dilemma argument against the existence of free will (“autonomy”):

- Either our choices are necessitated or they are not.

- If they are necessitated, then we do not control them, and so we lack autonomy.

- If they are not necessitated, then they are random, and so we lack autonomy.

- Therefore, we lack autonomy.

— Russ-Shafer Landau, The Fundamentals of Ethics (2018), p. 187 [formatting mine]

In my reply to Nahm’s commentary, I point out that instead of trying to defeat this simple dilemma argument, from the 20th century onward metaphysicians have tended to move more toward “decoupling causal responsibility for an act (which determinism entails) from moral responsibility for it” (p. 807n23), which (if successful) might give us some wiggle room for holding people morally accountable for their actions even if free will doesn’t really exist. But even if such a project were doomed to failure, we’d still have societal grounds for legal accountability or similar approximations to genuine moral responsibility. So there’s no mystery in how even “ardent determinists can call out bad behavior or reasoning,” as I put it in my reply. Just consider how 20th-century philosopher Walter T. Stace argued this point:

You do not excuse a man for doing a wrong act because, knowing his character, you felt certain beforehand that he would do it. Nor do you deprive a man of a reward or prize because, knowing his goodness or his capabilities, you felt certain beforehand that he would win it.

Volumes have been written on the justification of punishment. But so far as it affects the question of free will, the essential principles involved are quite simple. The punishment of a man for doing a wrong act is justified, either on the ground that it will correct his own character, or that it will deter other people from doing similar acts….

Punishment, if and when it is justified, is justified only on one or both of the grounds just mentioned. The question then is how, if we assume determinism, punishment can correct character or deter people from evil actions.

Suppose that your child develops a habit of telling lies. You give him a mild beating. Why? Because you believe that his personality is such that the usual motives for telling the truth do not cause him to do so. You therefore supply the missing cause, or motive, in the shape of pain and the fear of future pain if he repeats his untruthful behavior. And you hope that a few treatments of this kind will condition him to the habit of truth-telling, so that he will come to tell the truth without the infliction of pain. You assume that his actions are determined by causes, but that the usual causes of truth-telling do not in him produce their usual effects. You therefore supply him with an artificially injected motive, pain and fear, which you think will in the future cause him to speak truthfully.

The principle is exactly the same where you hope, by punishing one man, to deter others from wrong actions. You believe that the fear of punishment will cause those who might otherwise do evil to do well….

The assumption on which punishment is based is that human behavior is causally determined. If pain could not be a cause of truth-telling there would be no justification at all for punishing lies. If human actions and volitions were uncaused, it would be useless either to punish or reward, or indeed to do anything else to correct people’s bad behavior. For nothing that you could do would in any way influence them. (Religion and the Modern Mind, 1952, pp. 289-291)

Parallel points could be made for concluding that an idea is true because one has good reasons for affirming it. Although machines as simple as calculators have no “choice” in how to solve arithmetic, nevertheless their solutions are completely caused by underlying computational activity that’s fully realized by solely physical processes—and yet there are simultaneously mathematical reasons to provide the solutions that calculators produce (making various arguments from reason moot).

In the quotation opening this section as a graphic, Russell was addressing William James’ views about “the will to believe.” This will infects survival researchers no less than those whose religious beliefs are more explicitly faith-based. Recall that in Braude’s opening approach in his BICS essay, he asks whether we are permitted to believe in discarnate personal survival, which is different from asking whether the evidence indicates that survival probably happens. The latter—Russell’s “the wish to find out”—is the tough-minded approach of the scientist. The former—James’ “will to believe”—is the soft-minded approach of those concerned merely with what they are allowed to believe in—most probably, what they would like to believe is true, not what’s likely to be true. This, of course, opens the door to an irrational propensity to favor comforting delusions over potentially uncomfortable truths, whatever the evidence for those truths. What’s more important—blissful ignorance for the sake of the bliss, or having a grasp of what’s actually going on around you? Knowledge has value for its own sake, independently of whether the (probable) truth makes us happier or not.

Lies, Damned Lies, and Survival Research: Post-Misrepresentation of the BICS Exchanges

“No good deed goes unpunished,” the old adage goes. Perhaps it’s time for a new one: “No statement goes undistorted.” Despite the fact that reincarnation researcher James G. Matlock exhibits a pattern of demonstrably “disseminating misinformation that is often difficult to erase again from the literature” (Nahm, 2022, p. 787) (like others defending discarnate personal survival), Nahm frequently treated Matlock as the last word on contentious subjects in his commentary on the summer exchanges (e.g., p. 785, 787, 791n6). It’s consequently notable that Matlock continues to mischaracterize my work (as he did in an earlier review) in his passing comments on the BICS exchanges in a new Psi Encyclopedia entry on critical responses to what Nahm dubbed reincarnation “before-cases”:

In addressing Michael Nahm’s assessment that strong early-bird cases provide some of the best evidence for reincarnation, Keith Augustine allows that they ‘would be impressive’, but ‘only if normal/conventional sources of information for ostensibly anomalous knowledge were not present’ in these cases. However, he avers, without substantiation, ‘we already know’ that ordinary sources of information account for the apparent memories. In a footnote, Augustine does not directly support this allegation, but refers to what he regards as a related issue, the ‘law of good enough’ evoked by Sudduth in his attack on the James Leininger case; but this has since been undermined by Matlock.

In the above quotation, I bolded an example of how Matlock (like Nahm) repeats a misrepresentation in order to shift the burden of proof. What I had actually said was that Nahm’s unsupported assertion that “Retrospective tampering is much more difficult and unlikely” in his prized before-cases (putative reincarnation cases investigated before the families involved met and so could not share details) “would be impressive only if normal/conventional sources of information for ostensibly anomalous knowledge were not present in before-cases, and we already know that they have been” (p. 380).

My point was that before-cases do not even constitute prima facie evidence for anything paranormal (reincarnation or otherwise) unless normal/conventional sources of information (or influence) have been ruled out in them, and I cited Sudduth’s careful analysis as an example of a before-case where normal/conventional sources of information not only failed to be excluded, but were actually found. I never said that ordinary sources of information were definitively uncovered in all before-cases, just that Nahm (and other reincarnation researchers) never ensured their absence. But that’s exactly what science requires researchers to do to make a prima facie case that something paranormal is going on in such cases. Matlock, like Nahm, merely attempts to shift the burden of proof off of reincarnation researchers to provide the promised “proof beyond a reasonable doubt” of reincarnation. Instead, they place the burden on anyone who dares to doubt that they have delivered the goods (such as agnostics about whether reincarnation occurs). Their obligation to demonstrate that reincarnation has occurred in the cases that they cite in favor of it is transmuted into an obligation on the unconvinced to show that it hasn’t occurred. That’s all fine and well for marketing your conclusions to a sympathetic audience—but don’t pretend that it’s science addressed to everyone.

Sudduth had earlier shown that normal sources of information for putatively paranormal knowledge that James Leininger ‘couldn’t have known otherwise’ were not, in fact, particularly “unlikely” in the Leininger before-case. Does this demonstrate that such normal sources definitely were available in all other before-cases? Of course not; but that’s not the point. The point is that bald proclamations about how unlikely they are need to be supported, not merely asserted. Anyone can assert anything. Supporting what you assert is another matter, and Nahm did not do that on this point in his BICS essay.

Incredibly, Matlock’s Psi Encyclopedia entry straw-mans my endnote #13 as alleging that we already know that putative memories of reincarnation are fully accounted for by “ordinary sources of information.” That I never said any such thing is immaterial to those who polemically aim to paint me in a certain way. Moreover, I don’t seek to even indirectly support this imaginary allegation by way of reference to the statistician’s law of near enough. In fact, I was quite explicit in that endnote that Sudduth had previously made an entirely different point to the one that I was making in the main text:

13. So much, then, for Nahm’s response to conventional counterexplanations of CORT already noted in the literature: “none of the critiques listed above applies to the strong before-cases in which written documents were made before the previous personalities were identified and the families met” (2021*, p. 40). And I haven’t even mentioned how spurious specific correspondences between one’s life and that of a (supposedly reincarnated) person can be manufactured from whole cloth due to the law of near enough (Sudduth, 2021, pp. 999-1000, 1006; cf. Angel, 2015, pp. 575-578), even when supposed correspondences are conflicting (Sudduth, 2021, p. 1022n62). (p. 392n13)

In the main text I was obviously addressing “conventional counterexplanations of CORT already noted in the literature” apart from Sudduth’s (relatively novel) point about spurious correspondences being generatable from whole cloth. Indeed, right after explicitly asking how reincarnation researchers have ruled out normal sources, I even added the qualifier “nonspurious” to be as clear as possible that I wasn’t addressing Sudduth’s other point about spurious correspondences: “The boggle factor for CORT requires the assumption that there is no normal source of any (nonspurious) factual correspondences” (p. 380).

And since my point was about the “the assumption that there is no normal source of any (nonspurious) factual correspondences,” the issue here wasn’t about the law of near-enough at all (the source of spurious correspondences), but about other than spurious potential normal sources of such correspondences, such as the possibility “that they were not investigated deeply enough” (p. 379), which is something that Sudduth had earlier demonstrated in the Leininger before-case apart from his independent concerns about the likelihood that some correspondences were spurious ones. In other words, Sudduth had previously shown that both spurious and nonspurious (but normal-means-informed) correspondences could account for the correspondences that reincarnation researchers appealed to as strong evidence for paranormality in the Leininger before-case.

Conclusion: Which Opposing Authors are the Good Ones?

In John Loftus‘ outsider test for faith, Loftus suggests that believers subject their own religious beliefs to the same degree of scrutiny that the faith claims of rival religions would receive from them. Presumably this procedure is designed to minimize the influence of confirmation bias, subconsciously or otherwise, on one’s conclusions.

I would recommend a similarly motivated test for survival research. If you’re skeptical of discarnate personal survival, ask yourself: Which survival sympathizers are the reasonable ones? (Chief on my list would be classic thinkers like C. D. Broad, H. H. Price, or Gardner Murphy, or contemporary ones like Carlos Alvarado, Alan Gauld, or David H. Lund.) Alternatively, if you believe in discarnate personal survival, ask yourself: Which survival skeptics are the reasonable ones? For the sake of maximizing self-awareness, understand “survival skeptics” to refer to authors who doubt the existence of both discarnate personal survival in particular and genuinely paranormal phenomena in general. With that broad definition in mind, can you think of any reasonable skeptical authors?

If you cannot, this says less about the traits of skeptical writers and more about your own intolerance for dissenting points of view. There are a large proportion of people who are skeptical of both survival and the paranormal, ranging from scientists to journalists to next-door neighbors, and they are not cookie-cutter clones from some monolith of “fundamaterialists” or “pseudoskeptics” (or whatever other childish label you want to slap on the other). No doubt there will always be some skeptics who are opinionated and pigheaded, but why waste your time on them? With so many different things competing for our attention during a finite lifetime, and in the interest of steel-manning, wouldn’t it be better to limit your attention to the reasonable opponents?

If you cannot name even one writer who reasonably doubts the existence of both personal survival and the paranormal, then I suggest that the problem lies with you, not with such writers. Instead of projecting your own insecurities outward on to those who challenge your beliefs, you would do better to pause to consider the reasons for your unwillingness to consider why a writer might come to a completely different conclusion than you do. If those with no dog in this fight can come up with lists of perfectly reasonable authors on both sides of the issue, then there’s no reason (apart from your own intransigence) why you can’t do it, too.