(2021)

Most (if not all) current and past believers in Abrahamic religions have heard the accounts of creation found in the book of Genesis. The stories of Adam, Eve, and their fall from grace have infiltrated the societies of many countries, and are revered by billions of people. A large number of believers insist that these stories are not only the inspired Word of God, but a literal historical account of past events. Do these events have any basis in actual history? Are these stories original to the Hebrew people? If not, what or who inspired the stories that so many hold true? A thorough examination of the history and mythology of the cultures surrounding ancient Israel will aid in answering these questions. First, we will look at the most common story of creation, the account found in Genesis, followed by an exploration of the creation myths of the oldest Mesopotamian culture, the Sumerians, in an attempt to determine if there is a connection to Hebrew mythology.

The Biblical Story of Creation

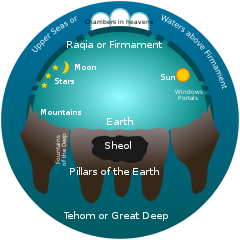

In Genesis 1, God created the heavens and the Earth and all that is within them. Verse 2 states that the Earth was “without form and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep.” God goes on to create light and separate the light from darkness, ending day one (verses 3-5). He then creates a “firmament” to separate the “waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament” to complete day 2. If one is to understand what a firmament is, a brief digression into ancient Hebrew cosmology is necessary.

According to the ancient Jewish model of the universe, the Earth was a flat disk set upon a foundation of pillars. Above the Earth stood a crystalline dome called the firmament, upon which the stars, sun, moon and planets revolve. Windows existed within the firmament to allow water to enter the Earth. Just above the dome lied the “waters which were above the firmament.” Above the waters is where the Heaven of Heavens, the realm of God, existed. Below the surface of the Earth was the underworld or Sheol and below Sheol, the primeval ocean or the “deep” mentioned in Genesis 1:2.[1]

In verses 9 and 10, God created dry land by gathering the waters into one place. He then created all plant life, which ends day 3 (verses 11 and 12). God begins and ends day 4 by creating “two great lights,” the sun and the moon as well as all of the other stars in the universe (verses 14-19). God created sea life on day 5 and commanded it to multiply (verses 20-23). Day 6 saw God create all land animals as well as man and woman. He commanded the humans to “be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.” After completing his creative acts, God declared that everything He had made was “very good” (verses 24-31).

The deity that created the universe in chapter 1 was called Elohim. Elohim is the plural form of the Hebrew word El (or Eloah) and is used as the word for any god, not just Yahweh.[2] The god El is also the name of the Canaanite supreme deity.[3] Rather than Elohim, chapter 2 uses the name Yahweh (YHWH) to refer to the Hebrew God. Verses 1-3 of chapter 2 finish the events of chapter 1 as it describes that God rested on day 7, setting it apart from the other days as holy. God’s name then switches from Elohim (the god or the gods) in verse 3 to Yahweh Elohim (the god(s), Yahweh) in verse 4.[4] After the name change, verses 4-25 seem oddly out of place when compared to chapter 1. Genesis 2:4 begins a retelling of the creation tale from a different perspective.

According to verse 5, no plants had been created yet due to a lack of rain and the fact that “there was not a man to till the ground.” It goes on to say in verse 6 that God caused a mist to come up “from the earth” to water “the whole face of the ground.” Verse 7 states that God made man from the dust and breathed in him “the breath of life.”

It is interesting to note the different methods of creation God used to create Adam in the first two chapters of Genesis. In chapter 1, God merely willed man and women into existence simultaneously. Whereas in chapter 2, God molds Adam from dust and breathes “the breath of life” into his body, showing attention to detail and intimacy between He and His creation. Also, in Genesis 1:26, God states “Let us make man in our image” before creating the first humans. Remember that chapter 1 uses the term Elohim to refer to God, which is the plural term.

The chapter continues to state that God planted a garden (verse 8) and placed Adam therein to attend to it (verse 15). God created a tree call the tree of the knowledge of good and evil and warns the man that “in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die” (verse 17). After warning Adam, God decides that “It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him an help meet for him” (verse 18). More modern translations such as the New Living Translation read “I will make a helper who is just right for him.”

Following his decision to give Adam the perfect helper, God creates all “beasts of the field” and “fowls of the air” out of “the ground” and has Adam give them all names (verse 19). Adam complies and names are assigned to all of the animals. After inspecting each of the animals, he does not find his perfect helper (verse 20). God then causes Adam to go into a deep sleep, removes one of his ribs, closes the wound and creates a woman from the rib (verses 21-23).

Chapter 3 is a continuation of the story started in chapter 2. This is evident by the literary style and the continued usage of the Hebrew term “Elohim Yahweh” to describe God.[5] The chapter begins with the temptation of Eve, Genesis 3:1-5.

Eve then eats the fruit from the tree of knowledge of good and evil and gives some to her husband who also eats. The two humans immediately feel emotions they have never experienced before, guilt and shame. Realizing that they are naked, they sew fig leaves together to hide their bodies (verses 6-7). God then takes a stroll through the garden during the cool evening and calls out to His creation, asking them where they are (verse 8). Adam and Eve come out of hiding and admit that they heard God coming and hid out of fear and shame due to the realization that they were naked. God asks them who informed them of their nakedness and wants to know if they have eaten from the forbidden tree.

Adam immediately blames Eve, who then blames the serpent (verses 12-13). God then curses the snake, stating that it will no longer have the ability to walk. He also mentions that He will cause hostility between the snake and the woman and between the offspring of the snake and that of Eve (verse 14-15). Eve receives the punishment of painful childbirth and the humiliation of being ruled over by her husband. As for Adam’s punishment, he has to labor to grow food in the soil that God has cursed due to his disobedience. The Earth will now produce thorns and thistles to make his job harder. God then makes the pair some new clothes out of animal skins and kicks them out of the garden, guarding it with two mighty angels armed with flaming swords (verses 14-24).

After reading these two stories, one may be wondering why it is that chapter 1 seems so different when compared to chapters 2 and 3. In antiquity, the Hebrews lived in a divided kingdom. The northern kingdom was called Israel and the southern kingdom, Judah. This division of the people occurred around 931 BCE, after the death of King Solomon.[6] The stories of creation are different because Genesis 1 was written in the northern kingdom of Israel between 900-700 BCE and Genesis 2 was written in the southern kingdom of Judah as early as 950 BCE. The northern kingdom writers use the term Elohim to refer to their God and are therefore known as the Elohists. The southern kingdom writers are known as the Yahwists due to their use of the tetragrammaton YHWH or Yahweh when referring to God. Since the kingdom of Israel was divided, it is reasonable to assume Israel and Judah created their own, separate, traditions of how their God created the Earth and all that is within it. The two accounts of creation were later combined and edited by Ezra or Nehemiah after the Jewish exile in the 5th century BCE.[7]

The Sumerian Creation Stories (2150-1626 BCE)

The earliest examples of written literature were created by the Sumerian people in around 3400 BCE.[8] They wrote many stories to explain a world they could not even begin to understand. Their library of myths is vast and can be confusing. One of the sources of confusion is the fact that they had many different names for their gods. For example, the god of wisdom and fresh water goes by the name of Enki in most of their mythology but he also has the following names: Ea, Enkig, Nudimmud, and Ninsiku. Similarly, the mother goddess Ninmah, Enki’s wife, goes by the these names: Ninhursaga, Ninhursanga, Nintud, Nintur, Ninmena, Belet-ili, Mami, Damkina, and Damgalnuna. Therefore, in order to reduce the chance of confusion, for the purpose of this discussion, the name of the god of wisdom will always be written as Enki and the mother goddess, Ninmah and the alternate name will be provided in parenthesis.

The most important god in the Sumerian culture was probably Enki. He was brother to Enlil, god of the atmosphere, son of Anu, the god of the sky and Namma, the primeval mother goddess of the sea. Excavation in the Sumerian city of Eridu uncovered a shrine dedicated to Enki dating to 5400 BCE, which corresponds to the date of the city’s founding. The Sumerian pantheon was revered by the Babylonians but by the time their empire ruled the Fertile Crescent, Enki had been surpassed by his son Marduk as the most important of the Mesopotamian gods.[9]

Enki and Ninmah

In the Sumerian story Enki and Ninmah, the Anuna (elder gods) rule over the Igigi (younger gods). The Igigi become tired of carrying crushed earth in baskets as ordered by their oppressors and appeal to Enki for help. Enki is sleeping when his mother Namma hears the cries of the Igigi and wakes her son. She urges Enki to create creatures to serve as substitutes for the gods so that their anguish at the hands of the Anuna can be alleviated.

Enki was annoyed at being awoken, but agreed to make the creatures. He asked his mother to get some clay from the top of the Abzu (or Apsu), the subterranean aquifer he calls home, and suggested that Ninmah, fertility goddess of the mountain and his wife, assist her. Namma, with the assistance of Ninmah, then gave birth to the human race using the clay from Enki’s home. Upon creating the first humans, Ninmah decreed that the task of carrying the baskets of clay would no longer be that of the gods, but of all humans.

After the creation of the humans, the gods had a feast to celebrate the birth of humanity, their new found freedom and Enki’s wisdom. During the party Enki and Ninmah had too much to drink and got a little tipsy and then Ninmah began to boast about her part in the creation of humans.

“Man’s body can be either good or bad and whether I make a fate good or bad depends on my will.”

Enki replied, “I will counterbalance whatever fate—good or bad—you happen to decide.”[10]

Ninmah then picked up the clay of Abzu and proceeded to create a group of humans without assistance. She first created a man who lacked the ability to reach out with his arms or grasp with his hands. Enki destined that man to serve the king because of his inability to steal. Next, she formed a man who was blind and Enki gave the blind man the gift of music and destined him to become a minstrel to the king. Ninmah then fashioned a third human from the clay who had paralyzed feet. Enki destined this man to become a silversmith. For her fourth creation, Ninmah formed a man who was incapable of holding back his urine or semen. Enki cured his affliction with a magical bath, dispelling the demon from his body. Ninmah’s fifth creation was an infertile woman, who was to become a prostitute. Enki showed mercy to the woman and destined her to become a weaver in the queen’s house. Performing her sixth and final act of creation, Ninmah formed a person without sex organs. Enki called this person a eunuch and placed them in the service of the king. A defeated Ninmah then threw the clay to the ground and Enki retrieved it.

Enki decided to test his wife by making people of his own from the clay. Enki first formed a woman who had difficulty giving birth. Ninmah was unable to reverse her fate. He then made an old man who was unable to stand or talk, who had heart, lung and gastrointestinal problems. Ninmah attempted to feed the man but was unable to help him eat. She attempts to help the man stand, but failed. She spoke to the man but did not get a reply. Frustrated, Ninmah complained that Enki had crafted a being that was neither alive nor dead. Enki pointed out that he was able to improve the lives of all of Ninmah’s creations without difficulty and noted that she could not do the same for his, proving to her that her wisdom did not surpass his own. Enki then reassured his wife of her importance and the other gods watching praised Enki for his wisdom.[11]

There is a similar creation motif between this Sumerian myth, and Genesis 2:7, man being made from earth. Namma, Enki and Ninmah all created humans from clay and God made Adam “of the dust of the ground.” Being created from earth is not the only common theme that can be gleaned from a comparison of these myths. In Enki and Ninmah, when both of the titular characters created their respective humans there is one thing that they all share in common, an affliction that they are incapable of changing. Similarly, in the Genesis 3:15-19 we learn of God’s punishment of Adam and Eve.

Adam and Eve were tempted by the serpent to eat the forbidden fruit, disobeying God’s command. As a result, God punished them, leading to afflictions that they could not change; painful childbirth for Eve and hard physical labor for Adam. According to the Bible, the punishments incurred by Adam and Eve have been passed down to humans. The authors of both stories are attempting to explain why there is pain and suffering in the world and do so in different ways. In the Hebrew mythology, humans are at fault for sickness and death due to Adam and Eve’s rebellion. This Sumerian myth however places the blame on prideful and flawed gods. Both stories also explain why people have to work. In nearly all Sumerian myths involving the creation of humans, Enki creates them in order to allow the gods to rest. In Hebrew mythology, Yahweh tells Adam that by the sweat of his face he shall eat his bread and that the ground is cursed due to his failure to keep His command.

Enki and Ninhursaja (Ninmah)

The Sumerian myth Enki and Ninhursaja details the exploits of Enki and his wife Ninmah (Ninhursaja) in the city known as Dilmun, the home of the gods on Earth. This city was described as “virginal,” “pristine,” a land where no one suffered from disease, one where well-being was not affected by age and where sadness could not be found. Enki’s daughter Ninsikila became disillusioned with her life in Dilmun. She didn’t see the benefit of living in a city without a dock for trade or without fields to grow grain and other vegetables. She complained about it to her father. Enki then blessed Dilmun and the next day it became a fertile garden paradise. After the transformation of the land, Enki and Ninmah made love and she became pregnant. The development of her child was much different than human children because instead of nine months gestation, Ninmah carried the child for nine days, with one day equating to one month. She then gave birth to a daughter, Ninnisig. After the birth of her daughter and when spring arrived Ninmah left the garden of Dilmun to continue her duties of nurturing all living things, leaving Enki alone with his daughter.

After the departure of his wife, Enki missed her presence and longed for the day of their reunion. One day Enki saw Ninnisig walking along the river bank and was entranced by her beauty. He boarded his ship with his attendant Isimud and sailed across the river to Ninnisig. Upon arrival at the river bank, Enki jumped out of the boat and made love to her, mistaking her for his beloved Ninmah. Ninnisig became pregnant and gave birth a daughter, Ninkura, in just nine days. When Ninkura became an adult, Enki again saw a beautiful woman by the river bank and he and Isimud went to investigate. Enki again mistakes her for Ninmah and made love to Ninkura, who becomes pregnant and gave birth to Ninimma in just nine days. Following the same pattern, Enki ultimately impregnated Ninimma, who in nine days gave birth to Uttu.

Ninmah (Nintur) appeared before Uttu and warned her to beware of Enki’s advances and informed her that there would be a day when he would set his gaze upon her. After the warning, Ninmah again departed. As one would expect, Enki did notice Uttu’s beauty and showed up at her home, thinking that his wife had finally returned. He attempted to charm her into sleeping with him but was unsuccessful. Uttu remembered Ninmah’s words and told her father that she would not make love to him unless he went out into the garden and retrieved “cucumbers, delicious apples with their stems sticking out and grapes in their clusters.” She went on to say that only when he delivered these foods to her would she give herself to him. Enki quickly carried out the task and the food was delivered as requested. Uttu gave Enki consent and the two make love. However, pregnancy was not the outcome, as Enki’s seed ended up on Uttu’s thigh after the act. Ninmah returned and discovered what had occurred. Removing Enki’s seed from Uttu’s thigh, she instructed Uttu take Enki’s seed and sow eight new plants that had never grown in the garden before. Nine days after sewing the seed, the new plants were finished growing.

Not long after that, Enki noticed the new plants growing in the garden and realized that he had not assigned them a destiny. He asked his attendant Isimud if he recognized the plants and could identify them. Isimud somehow knew the names of the new plants and encouraged Enki to eat each of the plants so that he may gain a better understanding of them and therefore declare a proper destiny for the new flora. Enki then proceeded to eat the eight plants that Uttu had created from his seed. Ninmah discovered what her husband had done and was furious. She appeared before him and cursed him, telling him that she would no longer look upon him “with the life-giving eye.” He had incurred a death sentence.

Enki became very ill, nearly at the point of death, while the other gods could do nothing but watch. Some historians believe that the text implies that Enki became pregnant. The only one who could heal him is Ninmah, who was nowhere to be found. One of Ninmah’s creatures, a fox, went to find his master and told her or Enki’s condition. Ninmah realized that she did not wish her husband to die, so she went to the temple where he was being cared for to help him.

Ninmah arrived at her dying husband’s side and asked him to “sit by my vagina.” She then asked him eight times where he hurt. Enki answered her by naming specific body parts (the top of his head, his hair, nose, mouth, throat, arm, ribs and side). Ninmah then took each of Enki’s afflictions upon herself and gave birth to eight deities, thereby healing Enki.[12]

There are several similarities between this Sumerian tale and the Genesis account. The garden paradise of Dilmun and the garden of Eden share several common traits. Both gardens were lush and food was plentiful; both were home to beings who do not grow old or get sick; both gardens were created by deities; both gardens grew forbidden fruits that would prove detrimental to their inhabitants. In the Genesis account Eve was tempted by the snake to eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, a temptation to which she succumbed. Much like Eve, Enki was tempted to eat the eight new plants by his attendant Isimud and subsequently, like Eve, succumbed to the temptation. Eve, the supposedly inferior creation, gained wisdom by eating the forbidden fruit; conversely, Enki, the god of wisdom, foolishly chose to eat Uttu’s new plants. Yahweh and Ninmah delivered similar judgments following the eating of the forbidden fruit, death. Both deities also showed mercy to their respective offenders. Yahweh delayed Adam’s punishment for some 900 years (Genesis 5:5) and Ninmah healed Enki by taking on his affliction and birthing the eight new gods. Apart from all of the aforementioned similarities, there is one commonality that is striking, a woman created from a rib.

According to Genesis 2:22, God took a rib from Adam and fashioned Eve from it, providing Adam with his wife. According to the above Sumerian story, Enki told Ninmah that his rib was hurting and she gave birth to the goddess Ninti, providing Enki with a daughter. The literal definition of the name Ninti is lady of the rib. This name is comprised of two Sumerian words, nin (lady) and ti (rib).[13] As mentioned above, the Yahwist account of creation, Genesis 2-3, was written around 950 BCE and Enki and Ninhursaja, between 2150-1750 BCE.

The Enuma Elish

This myth is possibly the oldest tale told by the Sumerian/Babylonian people. It tells the story of the creation of the universe, the gods, humanity and the birth and rise of Marduk. Marduk was the son of Enki and Ninmah and would become the deity of choice of the Babylonian empire during the reign of Hammurabi (1792-1750 BCE).[14]

According to the Enuma Elish, in the beginning, before anything was formed, there was only darkness and undifferentiated water swirling in a sea of chaos. The waters eventually divided into sweet, fresh water, known as the god Apsu, and salty, bitter water, the goddess Tiamat. The first generation of gods had arrived. After their parting, the water came together again and created the second generation of gods, twin deities known as Lahmu and Lahamuh. Then came the third generation of gods, Anshar and Kishar, who begat the fourth generation, Anu. Anu was the father of the fifth generation. His son Enki (Nudimmud) was the strongest, both in physical power and wisdom, of all of the gods.

The younger gods were a loud and rowdy group. Their noise disturbed Apsu’s sleep at night and distracted him from his work during the day. Apsu sought the advice of his Vizier, Mummu, on which action, if any, he should take. Mummu convinced Apsu that the younger gods should be destroyed. Apsu told his mate Tiamat of his plan to kill the younger gods and she was horrified. After learning of his plan, Tiamat warned her great-great-grandson Enki of the sinister plot. Enki devised a scheme to end the threat once and for all. He cast a spell upon Apsu, causing a deep sleep to fall upon the king of the gods. Mummu was with him and was paralyzed with fear at the mere sight of the mighty Enki. With Apsu unable to stop him, Enki slew the elder god and his Vizier with minimal effort. After the destruction of Apsu and Mummu, Enki took Apsu’s corpse and created a home for he and his wife Ninmah (Damkina). Enki and his wife then gave life to the sixth generation of gods, a son, Marduk.

Tiamat learned of this action and felt angry and betrayed. Were it not for her warning, her husband would still be alive and would have succeeded with his plan to destroy the younger gods. She had warned Enki out of a sense of duty, a sense of love. She didn’t want her children to be destroyed but now she was beginning to think that Apsu had the right idea all along. Even her own family had betrayed her. It was now clear to her that something must be done to deal with the threat of these young traitors. She consulted her advisor Quingu (or Kingu) who advised her to declare war on the younger gods. She heeded his advice and rewarded Quingu with the Tablets of Destiny, which legitimized his rule of the gods and gave him control of the fates. Quingu proudly wore the sacred Tablets of Destiny as a breastplate. Tiamat named Quingu her champion and created eleven terrible monsters to destroy her children.

The younger gods fought with all of their might but even with the aid of the most powerful among them, Enki, the futility of their efforts and the power of their foes became clear. Realizing that their enemies seemed invincible, the brave warriors accepted that they were destined to lose both the war and their lives, but fate, it seems, had other plans. A champion emerged from among them, Marduk, son of Enki. Marduk defeated Quingu without difficulty and bound him, amazing the younger gods. Seeing the defeat of her champion enraged the elder goddess further and a fierce battle erupted. Marduk shot an arrow into Tiamat’s belly, splitting her in half. When Tiamat died, two rivers, the Tigris and Euphrates, emerged from her eyes. The champion Marduk stood over Tiamat’s corpse victorious and created the heavens and the earth from her lifeless body. The hero bound Tiamat’s eleven terrible monsters to his feet as trophies.

Marduk returned to his home and received a hero’s welcome and called for the treacherous Quingu to be brought before him. By defeating Quingu, Marduk earned the right to rule the gods and seized the Tablets of Destiny. All of the other gods praised Marduk for his great victory and admired the art of his creation.

Marduk consulted his father Enki and they decided to create humanity from the remains of the traitor who urged Tiamat to destroy his brethren. Quingu is charged and convicted of the crime, his sentence, death. From the blood of Quingu, Enki, at the command of his king, created Lullu, the first man, and destined him to serve as a helper to the gods in their never ending endeavor of maintaining order in the universe. Finally, with humanity at their side, the gods could rest and enjoy peace, a peace won by the most powerful god among them and true king, the mighty hero Marduk[15]

Notice that in the beginning of this story, there is a swirling watery chaos that is brought into order by the divine action of the waters dividing from the waters. The Genesis account of creation describes a similar phenomenon when God created the “firmament” in Genesis 1:6.

In Enuma Elish, Tiamat took the advice of Quingu to declare war on the younger gods. Acting on his advice, she and her champion become the antagonists of the story and are defeated by Enki’s son Marduk. In the Genesis account, the serpent became the antagonist of the story after tempting Eve to disobey God’s command. He told her that if she and her husband ate the forbidden fruit that they “shall be as gods, knowing good and evil.” Eve listened to the bad council of the serpent and ate the forbidden fruit, then shared it with Adam who also eats. Once God discovered Adam and Eve’s transgression, He punished the serpent, both Adam and Eve and ultimately all of mankind (Genesis 3:1-19). Both stories feature a character who gave bad advice to someone who lacked the ability to make rational decisions, the serpent to Eve due to innocence, Quingu to Tiamat due to grief. Additionally, both of the givers of foolish council were punished by their respective deities.

The numbers six and seven are important to the Genesis story. God created man on the sixth day of creation and rested on the seventh. It appears these numbers were important to the Sumerians as well. The Enuma Elish was written on seven stone tablets. In the myth the sixth generation of gods, Marduk, ordered Enki to create mankind, ensuring that the seventh generation could rest.

The Epic of Atrahasis

The Epic of Atrahasis is the youngest of the Sumerian myths discussed thus far, dating to sometime between 1647-1626 BCE.[16] This myth explains the plight of the younger gods, the creation of humanity, the great flood and its immediate aftermath. The original Sumerian flood myth was written around 2300 BCE resulting in the Eridu Genesis. The Epic of Atrahasis acts as an assemblage of Sumerian myths with some minor changes, specifically to the creation story.

We begin this myth shortly after the creation of the cosmos and the gods. As usual, the elder gods were forcing the younger gods to do their bidding, mandating that they dig the Tigris and Euphrates rivers as well as their respective deltas and tributaries. They were then forced to use the excavated material to form the mountains. This enslavement went on for over 40 years. One of the younger gods began calling for an end to the forced labor and urged his brethren to rise up and declare war on their foreman, Enlil. After years of back breaking work, the lesser deities finally reached their limit and listened to the call for sedition, an insurrection was in order. Through the cover of darkness, they approached the temple of Enlil, god of the atmosphere. Enlil was surprised to see a group of armed workers at his doorstep, so he sent his brother Enki (Ea) to uncover their grievances and address them appropriately.

Enki asked the younger gods to tell him which of them was responsible for instigating their rebellion. Unwilling to betray one of their own, all of the gods claimed responsibility even going so far as to state that their intention was to bring war upon the elder gods as revenge for their enslavement. Enki offered the younger gods a compromise. He told the mob that he would ask his wife Ninmah (Belet-ili) to create humanity and cast upon him the forced labor commanded by Enlil. The younger gods agreed to this proposition and Enki called upon Ninmah (Mami), asking her to create the human race so they could do the work of the gods. Ninmah agreed under the condition that humanity was not to become slaves of the gods but their coworkers. She goes on to tell her husband that she would do as he had requested should her request is honored and if he provided the required clay.

Enki proposed his plan to create humans to the elder gods. He suggested that in order for the plan to work, one of the gods must be sacrificed and both his blood and flesh must be mixed with the clay so that mankind possessed the spirit of the gods, therefore not forgetting them. The elder gods agreed and ordered that the god responsible for inciting the rebellion be sacrificed. An investigation initiated and it was discovered that the god at fault was not of the younger gods but of the elder, the intelligent and inexperienced Geshtu (Aw-Ilu).

Enki gathered some clay from the Abzu and Geshtu was killed. Ninmah mixed his blood and flesh with the clay and formed the first human, a human who had the spirit of the gods. The younger gods praised Ninmah and bowed to her, kissing her feet. Ninmah instructed the younger gods that humanity would do their work but they were to be treated as coworkers, not slaves.

The motive for creating humans, as in most of the Sumerian creation myths, is relief for the younger gods. There is one key difference in this story that sets it apart from the others. In the above tale, man is created with the spirit of the gods. The gods chose to sacrifice one of their own and infuse their essence into humanity, making humans in their image. They gave humanity a soul. These actions by the gods closely mirror God’s actions in the Elohist account found in Genesis 1:26-27. The methods of creation are similar as well.

God’s method of creation is again similar to that of Ninmah and Enki as all use dirt as their construction material. The Sumerian myths and the Genesis account both specifically say that humans are formed intentionally from dirt. Also like the Sumerian myth, God placed a soul into his creation.

Differences in Hebrew and Sumerian Mythology

There are several similar themes present in both Sumerian and Hebrew mythology. One key difference that becomes apparent when studying each culture’s literature is their view on their respective deities. A defining characteristic of Hebrew mythology is the concept of monotheism. Israel only worshiped a single all-powerful deity and therefore had to be more creative when exploring many of the same concepts mentioned in Sumerian texts. Having fewer characters at their disposal helped the Hebrews create a shorter, simpler and easier to follow story with a definitive main character. The Sumerians often used the ineptitude of their pantheon of gods as a metaphor for human behavior or as a reason for human suffering. The Jewish authors showed their God as all-powerful, even tempered and wise in both accounts of the Genesis myth. Having fewer gods also leads to a decreased need to tell the same story multiple times. There are two creation accounts portrayed in the book of Genesis. Sumerian mythology, on the other hand, tells their complex tale of creation multiple times with little to no internal consistency between the stories.

Analysis and Conclusion

Given the evidence provided, it is clear that the story of creation found in the book of Genesis is not entirely original to the Hebrews. Many of the ideas found in the biblical tradition are also found in the much older myths of the Sumerians, and are shared by cultures around the world. Why is it that the Jews borrowed some of the ideas of their neighbors?

Map of Sumer[17]

According to Genesis 11:31, Abram (later Abraham) lived in the Sumerian city of Ur. The historicity of Abraham is debated, but more conservative scholars place Abraham’s journey to Canaan at around 2000 BCE, before the creation of the Hebrew accounts found in Genesis, but after most of the Sumerian accounts.[18] Supposing that he existed, Abraham was a Sumerian, and therefore would have been very familiar with the Sumerian pantheon of gods and the stories of them. He most likely worshiped the aforementioned deities until he shifted his devotion to El.

Even if Abraham was a mythical figure, the fact remains that the Sumerians are the first civilization to settle Mesopotamia, founding the city of Eridu around 5400 BCE. Given the human instinct for exploration, it is certain that the Sumerians would expand their territory and give rise to the remaining civilizations of the Fertile Crescent. Due to migration and time, their mythology would inevitably change and evolve into the various creation accounts found in the region, while leaving the mythology of their homeland largely intact.

The evidence also shows that a people’s mythology within their own culture can change with time. Aspects of the god Enki change quite often in Sumerian mythology, as he goes from the de facto god of creation in Enki and Ninmah, to performing the act of creation at the order of Marduk in the Enuma Elish. The stories in Genesis are affected by this phenomena as well. Genesis chapter 1 tells of an impersonal God who creates by sheer force of will in six days, resting on the seventh. Genesis chapter 2, by contrast, shows a personal God who makes man in his own image out of the dust of the Earth during an unspecified time period.

Evolving mythology is to be expected as a culture changes or encounters something that they don’t understand or that causes fear. Creating myths to explain the ideas or situations that troubled the ancients was their way of alleviating those fears and doubts. All ancient cultures were similar in that regard—they all sought answers to erase their ignorance. Modern human cultures are no different. Our thirst for knowledge is irresistible, and thanks to our innate curiosity, we have ascended to a place that our ancestors could have never imagined—an understanding of our world.

Appendix

| 900-700 BCE | 950 BCE | 2150-1750 BCE | 2150-1750 BCE | 2150-1750 BCE | 1647-1226 BCE | |

| Genesis 1 | Genesis 2-3 | Enki and Ninmah | Enki and Ninhursaja | The Enuma Elish | The Epic of Atrahasis | |

| Waters separate in beginning | × | × | ||||

| Man made in the image of god(s) | × | × | ||||

| Man formed by a god from earth | × | × | × | × | ||

| Garden paradise | × | × | ||||

| Woman made from rib | × | × | ||||

| Temptation and judgment | × | × | ||||

| Acceptance of bad counsel leads to negative outcome | × | × | × | |||

| Fruit/food cause suffering | × | × | ||||

| Explains why humans suffer | × | × | ||||

| Explains why humans must work | × | × | × | × | ||

| Mercy shown to offenders | × | × | ||||

| Importance of numbers 6 and 7 | × | × |

Notes

[1] N. F. Gier, God, Reason, and the Evangelicals: The Case against Evangelical Rationalism (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1987), Chapter 13.

[2] Encyclopaedia Britannica, 15th ed., s.v. “Elohim.”

[3] Ira Spar, “The Gods and Goddesses of Canaan” (April 2009). The Met Museum website. <https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/cana/hd_cana.htm>.

[4] See Genesis 2 in Greek/Hebrew Interlinear Bible Software (Katwijk, The Netherlands: Scripture4all Foundation, 2008).

[5] See Genesis 3 in Greek/Hebrew Interlinear Bible Software (Katwijk, The Netherlands: Scripture4all Foundation, 2008).

[6] Joshua J. Mark, World History Encyclopedia, October 26, 2018, s.v. “Israel.”

[7] Encyclopaedia Britannica, 15th ed., s.v. “Genesis: Old Testament.”

[8] Evan Andrews, “What is the Oldest Known Piece of Literature?” (August 22, 2018). History.com, A&E Television Networks. <https://www.history.com/news/what-is-the-oldest-known-piece-of-literature>.

[9] Ira Spar, “Mesopotamian Creation Myths” (April 2009). The Met Museum website. <https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/epic/hd_epic.htm>.

[10] See Enki and Ninmah in Oxford University’s Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature.

[11] See Enki and Ninmah in Oxford University’s Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature.

[12] See Enki and Ninhursaja in Oxford University’s Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature.

[13] Xue Lin, “English Translation of Sumerian Words” (February 23, 2018). Snow Mountain web log. <https://xue-lin.com/english-translation-of-sumerian-words>.

[14] Joshua J. Mark, World History Encyclopedia, May 4, 2018, s.v. “Enuma Elish—The Babylonian Epic of Creation (Full Text).”

[15] Joshua J. Mark, World History Encyclopedia, May 4, 2018, s.v. “Enuma Elish—The Babylonian Epic of Creation (Full Text).”

[16] Jona Lendering, “The Epic of Atrahasis” (October 12, 2020). Livius.org website. <https://www.livius.org/sources/content/anet/104-106-the-epic-of-atrahasis/>.

[17] P. L. Kessler, World History Encyclopedia, July 11, 2013, s.v. “Map of Sumer (Illustration).”

[18] John S. Knox, World History Encyclopedia, June 22, 2020, s.v. “Abraham, the Patriarch.”

Copyright ©2021 Jason Gibson. The electronic version is copyright ©2021 by Internet Infidels, Inc. with the written permission of Jason Gibson. All rights reserved.