Old Testament Life and Literature (1968)

Gerald A. Larue

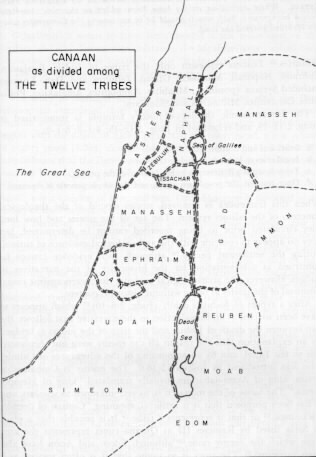

Chapter 9 – The Settlement of Canaan

THE Hebrews entered a land with its own highly developed culture. During the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages, Canaan was dotted with strong, walled, industrial and trade centers surrounded by orchards, vineyards, grain fields and pasture land. Wool and flax were woven and dyed with the rich purple obtained from the Murex shellfish. Wine, dried fruits, grain and milk products were also produced. Minerals from the Wadi Arabah were smelted and fashioned into ornaments, tools and weapons for sale and exchange. The rich lived in magnificent villas built around central courts; the poor dwelt in hovels massed together. Slaves captured in battle, and the poor who sold their families and themselves to meet debts, contributed to the power and wealth of the few.

Canaanite religion, a fertility or nature religion, reflected the major concerns of the populace – increase and productivity. Until recently, information about Canaanite belief was drawn largely from the negative statements in the Bible, but since 1928 new data has been forthcoming. While plowing a field, a farmer discovered a Canaanite necropolis at Ras es-Shamra in northern Syria at a point along the seacoast to which the “finger” of Cyprus appears to be pointing. Excavations began in 1929 under the direction of Claude F. A. Schaeffer of France and have continued since with only a brief interruption during World War II. The necropolis belonged to the ancient city of Ugarit, known to scholars from references in the El Amarna texts. The city was destroyed in the fourteenth century by an earthquake and then rebuilt, only to fall in the twelfth century to the hoards of Sea People. It was never rebuilt and was ultimately forgotten. One of the excavator’s most exciting discoveries was a temple dedicated to the god Ba’al with a nearby scribal school containing numerous tablets relating the myths of Ba’al written in a Semitic dialect but in a cuneiform script never before encountered. The language was deciphered and the myths translated, providing many parallels to Canaanite practices condemned in the Bible and making it possible to suggest that the religion of Ba’al as practiced in Ugarit was very much like that of the Canaanites of Palestine.

|

CHART VIII

| |||

| Years B.C. | Archae- logical Period |

Conditions and Events in Palestine

|

Conditions and Events Outside of Palestine

|

|

1500-1200

|

Late Bronze Age

| Canaan: a province of Egypt; dotted with powerful walled cities; city-state plan of government; extensive trade and industry; flourishing nature religion. Hebrews invade from the east (thirteenth-twelfth centuries). Philistines invade from the west and occupycoastal region (twelfth century). | EGYPT: weakened by war against Sea People unable to control Palestine

HITTITE nations collapses

|

|

1200-922

|

Early Iron Age

| Philistines establish city-states; Hebrews struggle to hold territory: period of the Judges; war with Canaanites: battle of Taanach; battles with Moabites, Midianites, Amalekites, Philistines;an abortive attempt at Hebrew kingship; the tribe of Dan is forced to migrate; the war against Benjamin | ASSYRIA: Under Tiglath Pileser I holds Syria until I 100

EGYPT: still weak |

The texts1 portray a divine hierarchy headed by the benign father-god El, a rather subordinate figure in some of the myths, and the mother goddess, Astarte, who appears in the Bible as Ba’al’s consort. The numerous children include: Ba’al, the god of rain or weather and fecundity; Yam, the sea god; Mot, god of death; Koshar or Kothar, the artisan god; Shemesh, the sun god; Anat, the sister-consort of Ba’al; and numerous other minor figures. One myth reflects the seasonal cycle which must have been basic for cultic observances. It tells of a battle for sovereignty of the land between Ba’al and Yam, in which Yam, defeated by magic weapons supplied by Kothar, is confined to the ocean bed. (Compare Prov. 8:29; Ps. 89:9 f.) The triumphant Ba’al builds a castle and, in a victory feast, extols his prowess in battle and his role of lord of the land. During the banquet, messengers from the uninvited Mot bring a challenge to Ba’al, and when Ba’al and Mot meet, the god of life is overcome by the god of death. Without rain Mot’s deathly powers begin to encroach upon the fertile land. El descends from his throne and sits on the ground pouring ashes on his head and, in a ritual act, gashes his face, arms, chest and back (cf. I Kings 18:28). Anat too, conducts mourning rites, weeping over hill and mountain as she searches for the dead god. Finally, having discovered Ba’al’s fate through the sun god, Anat encounters and defeats Mot, grinding him and scattering his remains. In some manner not explained, Ba’al was revived and life returned to earth. For the seasonal pattern of the ritual, Ba’al’s death symbolized the aridity of summer; the defeat of Mot symbolized the time of harvesting crops and fall sowing; and the rebirth of Ba’al symbolized the coming of the autumnal rains. Numerous “stage directions” point to some form of dramatic enactments.2 Within this and other myths, gods perform sexual and cultic acts prohibited in the Hebrew religion, suggesting that some biblical prohibitions may have been directed against participation in Canaanite religion as much as against some violation of accepted mores.

THE CANAANITE GOD BA’AL. A limestone stele found at Ras es-Shamra portrays Ba’al wearing a conical headdress with horns, a short kilt, and a sword strapped to his side. His upraised right arm is poised to hurl a thunderbolt, and his left hand holds a spear of lightning, stylized to represent a tree. He stands above the undulating hills, or perhaps the waves of the ocean. The small figure below the tip of the sword is, perhaps, the donor of the stele.

As a god of productivity, Ba’al was well suited for the social and economic climate of Canaanite business society. There can be little doubt that the prophetic idealization of the wilderness period and the outcries for justice for the widow and orphan reflect Canaanite social mores which made it possible to seize every opportunity to profit from the death of a neighbor’s father or husband. On the other hand, in another Canaanite tale in which a certain Dan’el (or Daniel) is a symbol of those who maintain social order, Dan’el judges the cases of widows and orphans, and this text sets forth the responsibility of a son for his father, so that it should not be assumed that Canaan was without any moral code.

THE INVASION OF CANAAN

The only written reports of the Hebrew invasion of Palestine are found in Joshua and in the first chapter of Judges, both of which are part of the Deuteronomic history, and in Num. 13; 21:1-3, a combination of materials from J, E and P sources.3 It is clear that Joshua did not write the book bearing his name, for some passages reflect a post-conquest point of view (cf. “to this day” in Josh. 4:9; 5:9; 7:26; 9:27; 15:63) and Joshua’s death and burial are reported in Josh. 24:29 f. A number of inconsistencies and repetitions (cf. Josh. 3:17 and 4:10 f.; 4:8, 20 and 4:9; 6:5 and 6:10; 8:3 f. and 8:12; 10: 26 and 10:37; 10:36 and 15:14) have led some scholars to extend Pentateuchal sources into Joshua, but so thoroughly has the Deuteronomist integrated and overwritten the work that the analyses are not very satisfactory.4 As a result, serious difficulties are encountered in any attempt to reconstruct the invasion history.

The general picture presented in the book of Joshua is that of a swift, complete conquest by invaders who were enabled, through Yahweh’s miraculous intervention, to overcome the most powerful Canaanite fortress without difficulty, and who engaged in a program of massive annihilation of the Canaanite populace. Despite this picture numerous passages reveal that the conquest was not complete (cf. 13:2-6, 13; 15:63; 16:10; 17:12), and the impact of Canaanite life and thought through the period of the monarchy reveals the continuation of strong Canaanite elements within the culture.

The Deuteronomic interpretation of the invasion in terms of a holy war adds further problems to our efforts to understand what actually happened. Holy war was waged under the aegis of the deity. Battles were won not by might of human arms, but by divine action. The hosts of heaven assisted human soldiers who represented the family of worshipers, and battles were waged according to divine directions. Ritual purification was essential. Conquered peoples and properties came under the ban or herem and were “devoted” to the deity.5

GODDESS FIGURINE. A contemporary bronze cast made from a mold found in a Canaanite shrine from about 1500 B.C. uncovered at Nahariyah, which is located along the Palestinian coast, north of Acco. It is quite probable that priests or smiths at the shrine manufactured figurines for sale to worshipers. The goddess, who may be Astarte, wears a horned headdress, like the goddess Hathor of Egypt, a tall peaked cap, and, perhaps, a string of beads.

Read Josh. 1-12, 23-24

The Joshua story opens with the Hebrews poised for attack on the eastern bank of the Jordan. Joshua, appointed by divine commission as the successor of Moses, sent spies into Jericho and, upon their return, made ritual preparations for the holy war. Sanctification rites were performed, for the people had to be a holy people (3:5). Miraculously, the Jordan River was crossed (ch. 3) and the purified people entered the land promised by Yahweh. The rite of circumcision was performed, signifying the uniting of all to Yahweh6 and Passover was observed. Assurance of success came with the appearance of the commander of Yahweh’s armies. Through ritual acts, Jericho’s walls collapsed and the city was taken and devoted to Yahweh. Violation of the herem by Achan interrupted the smooth annexation of the land at Ai, and it was not possible for the invasion to proceed harmoniously until he and all encompassed in the corporate body of his family were exterminated. Subsequently Ai fell. Gibeon, through a ruse, was spared destruction. A coalition of frightened monarchs from Jerusalem, Hebron, Jarmuth, Lachish and Eglon attempted in vain to halt Joshua’s progress. Next, the Hebrews moved through the Shephelah, then northward into Galilee, completing the conquest north and south. The conquered territory was divided among the Hebrew tribes. Joshua died after making a farewell speech and performing a covenant rite (which interrupts the sequence) at Shechem.

Archaeological research has provided only limited assistance for the reconstruction of the invasion history. Excavation at Jericho produced no evidence for the period of the Hebrew attack because erosion had washed away all remains7 but there is no reason to doubt the tradition that Jericho fell to the Hebrews. The problem of Ai mentioned earlier must remain unsolved. Of the cities of the southern coalition both Lachish (Tell ed-Duweir) and Eglon (possibly Tell el-Hesi) have produced evidence of destruction in the thirteenth century; Hebron (Jebel er-Rumeide) is being excavated; Jarmuth (Khirbet Yarmuk) has not been explored; and Jerusalem, if it fell in the thirteenth century (cf. Josh. 15:63), was rebuilt and reoccupied so that it had to be reconquered when David came to the throne (II Sam. 5:6-9). Other sites, Bethel (Beitan), Tell Beit Mirsim (possibly Debir) and far to the north, Hazor (Tell el-Qedah) reveal thirteenth century destruction, supporting the thesis of a Hebrew invasion.

Read Judg. 1-2:5

Judg. 1:1-2:5 gives a different portrait of the invasion, which parallels certain parts of the account in the book of Joshua,8 but which omits any reference to the role of Joshua and simply announces his death in the opening verse. Battles for both southern and northern territories are reported, but individual tribes struggle for the territory allocated to them in Joshua, and the impression of united action by an amalgamation of all tribes is missing. It is possible that this account which may have taken written form as early as the tenth century, preserves a more factual record than the idealized Deuteronomic tradition, and probably was inserted into the Deuteronomic material at a very late date.

Read Numbers 13, 21:1-3

The separate tradition preserved in Num. 13 and 21:1-3 also omits any reference to Joshua, and records an invasion from the south under the leadership of Moses. In preparation for the attack, Moses sent out spies who penetrated as far north as Hebron and brought back glowing reports of the agricultural productivity of the land. A battle with the people Arad resulted in the destruction of that site. There is no tradition of settlement or of further invasion from the south.

Despite the fact that archaeological and biblical sources are inadequate for any detailed or precise formulation of how the invasion was accomplished, a number of hypotheses have been developed. One analysis finds three separate waves of invasion: one from the south by the Calebites and Kenizzites, both part of Judah; one encompassing Jericho and its environs by the Joseph tribes, led by Joshua; and a third in the Galilee area.9 Another theory suggests that there were two Hebrew invasions separated by 200 years: a northern invasion under Joshua during the fourteenth century in which the Ephraimite hills were seized (perhaps to be related to the Habiru problem of the El Amarna correspondence) and a southern invasion around 1200 B.C. involving the tribes of Judah, Levi and Simeon, as well as Kenites and Calebites and perhaps the Reubenites, with Reuben finally migrating to the area northeast of the Dead Sea.10 Still another suggestion is that, prior to the thirteenth century, a number of Hebrews of the Leah tribes had united in an amphictyony centered in Shechem and that the Joseph tribes, under Joshua, invaded in the thirteenth century. The earlier occupation may have been a peaceful one, in contrast to the devastation wrought by Joshua’s forces. The Shechem covenant (Josh. 24) marked the union of the Leah group and the newcomers.11 The recital of further hypotheses could add but little to this discussion. No single view can be embraced with full confidence. Perhaps it will be enough to say that in the light of present evidence, the entrance of the Hebrews into Canaan was marked in some instances by bloodshed and destruction and in others by peaceful settlement among Canaanite occupants; and, although the thirteenth-century date best fits the invasion, it is likely that movement into the land by Hebrew people had been going on for at least 200 years.

THE JUDGES

The Hebrews were established in Canaan. Their status in the eyes of the Canaanites, how they organized their communities, what patterns of living they developed, and how they worshipped is not known. Some may have lived in tents (Judg. 4:17; 5:24) or caves (Judg. 6:2); others adopted the cultural patterns of settled society.

On the basis of archaeological study, it is surmised that three kinds of Hebrew settlements were developed.12 Villages were built on abandoned tells or in previously unoccupied areas. Where Canaanite cities had been destroyed, new dwellings were constructed amid the ruins. In some instances, by mutual agreement, Hebrews settled more or less peacefully among the Canaanites (Josh. 9:3-7). By comparison with Canaanite dwellings, Hebrew houses were poorly built. In new villages little attention was given to town planning and homes were constructed wherever the owner desired. Defensive walls were relatively weak and crudely composed, revealing limited mastery of structural engineering principles. Hebrew pottery, in contrast to well levigated, well fired Canaanite ware, appears quite poorly made. Some Hebrews ventured into Canaanite agricultural and commercial pursuits, others continued to raise flocks and herds (I Sam. 17:15, 34; 25:2). Despite efforts of a conservative element, fiercely loyal to old tribal ways, Canaanite cultural patterns were gradually assimilated. The unsettled nature of the times is revealed by the numerous destroyed layers from the thirteenth to eleventh centuries found in some excavations.

Literary information about this period is limited to the book of Judges, the third volume of the Deuteronomic history, which presents events within a somewhat stereotyped theological framework. When this theological structure is removed, a collection of early traditions reveals the chaos of the times. Numerous enemies threatened the loosely organized tribal structure; moral problems beset some communities; lack of organization afflicted all.

The book of Judges is usually divided into three parts: Chapters 1:1-2:5 which was previously discussed; Chapters 2:6-16:31, containing traditions of the judges; and Chapters 17-21, a collection of tribal legends. The second section, most important for reconstruction of Hebrew life, reports that in time of crisis, leadership came from “judges” (Hebrew: shophet), men best described as governors13 or military heroes, rather than as those who preside over law cases. These leaders were men of power and authority, individuals empowered by God to deliver the people-charismatic personalities.14 Apart from Abimelech’s abortive attempt to succeed his father (Judg. 9), no dynastic system appears to have developed, and the role of the judge when not delivering the people is not defined, although perhaps, as local leaders and chiefs, they did preside at the settling of disputes. Long terms of office ascribed to these men may reflect a protracted military struggle, an on-going office of protector-of-the-people conferred for life, or an artificial term of office designed by an editor. Attempts to formulate a chronology of leadership have proven fruitless, for the total of terms of office is 410 years – a period much too long for the interval between the invasion and the establishment of the monarchy. Events probably fall between the twelfth and the eleventh centuries.15 Leaders represent only the tribes of Judah, Benjamin, Ephraim, Naphtali, Manasseh, Gilead, Zebulun and Dan. Enemies included Syrians (possibly), Moabites, Ammonites, Amalakites, Philistines, Canaanites, Midianites and Sidonians.

JUG FROM THE LATE BRONZE AGE PROBABLY IMPORTED TO PALESTINE FROM CYPRUS. White decorative stripes have been added to the rich chocolate-brown background. Such vessels would be in use among the Canaanites when the Hebrews entered the land.

The Deuteronomic theology-of-history formula is summarized in Judg. 2:11-19, and reiterated in Judg. 3:12-15; 4:1-3; 6:1-2:

- Israel sins and is punished.

- Israel cries to Yahweh for help.

- Yahweh sends a deliverer, a judge, who saves the people.

- Once rescued, the people sin again, and the whole process is repeated.

When this framework is removed, stories devoid of the theological concerns of the editors remain. The age of the stories and how long they circulated prior to being recorded cannot be determined, but they do appear to coincide with the archaeological evidence of turmoil during the settlement pcriod,16 although such evidence cannot be construed as substantiation for the historicity of the narratives in Judges. However, the archaeological evidence does warn against casual dismissal of the stories as being without historical content.

Read Judg. 3:1-11

After a report of Joshua’s death (Judg. 2:6-10)17 which appears to have been written as an introduction to the narrative that follows, the gap between the death of Joshua and the time of the judges is bridged by an explanation that the reason all the enemy were not eliminated was to test Israel, and by an accounting of the adventures of Othniel who was introduced in Joshua 15:16 ff. The enemy is Cushanrishathaim, king of Aram-naharaim, usually translated “king of Mesopotamia.” The name of the monarch is, as yet, unknown to scholars, and it has been proposed that it is artificial, meaning “Cushan of doublewickedness,18 or that it represents a tribe.19 It is possible that a place in Syria listed by Rameses III as Qusana-ruma represents the area from which the enemy came,20 although Edom and Aram have also been suggested.21 The story is so vague that it is often treated as a transitional legend, designed to introduce the traditions of the judges.

Read Judg. 3:13, 15b-29

The story of Ehud the left-handed, recording deliverance from Moabites, represents a cherished memory extolling Ehud’s trickery and murder of Eglon, an account to be recited on occasions when Hebrew-Moabite hostilities were recalled. The narrative suggests a time when land on the eastern side of the Jordan north of the Arnon River, held by the Benjaminites, was seized by the Moabites. Eglon was murdered at Gilgal which seems to have been located a few miles west of the Jordan, and with Ephraimite assistance, the Moabites were pushed back across the Jordan. The location of the “sculptured stones” and Seirah (v. 26) are unknown. Possibly Jericho is the “city of palms” (cf. Deut. 34:3).

Read Judg. 3:31

The story of Shamgar appears to have been added after the Deuteronomists completed their work, for not only is the Deuteronomic formula missing, but the record of the battle of Taanach which follows begins with the death of Ehud (4:1). On the other hand, a rest period of eighty years (3:30), double that given elsewhere (3:11, 5:31, 8:28) may indicate that the Deuteronomists simply listed Shamgar without expanding his story. The title “son of Anath” perhaps refers to the hero’s village of Beth Anath (location unknown) or to his warrior role, for Anath was a goddess of love and war. Only Shamgar is depicted as an enemy of the Philistines.

Read Judg. 4-5

The battle of Taanach has been recorded in two accounts: one in prose (ch. 4), the other in poetry (ch. 5). Of the two, the poetic form is undoubtedly older,22 representing a victory song from a cultic celebration of Yahweh’s military triumphs, or, perhaps, a unit of folk literature, such as a minstrel’s song recalling victory over the Canaanites. As early Hebrew poetry coming from a time close to the events described (possibly eleventh century), the poem is of great literary importance, for it permits penetration into the period of oral preservation of tradition.

Read Judg. 5

The original poem begins in Judg. 5:4, the first two verses having been added later to provide a setting. The opening verses describe a theophany in terms of storm and earthquake as Yahweh comes from Seir in the mountains of Edom. The reference to Sinai, often treated as a late addition, may reflect the tradition that Sinai was in Edom. Troublous days are related in Verses 6 to 8. (The relationship of Shamgar ben Anath to the judge of the same name is not known.) Verse 8a defies accurate translation and Verses 9 and 10 are asides by the minstrels, expressing respect for the volunteer warriors. Deborah and Barak, Hebrew heroes, are called to lead against the foe, and tribal responses to the challenge are recorded. It is quite clear that whatever amphictyonic links may have existed were not compelling enough to make all groups participate. Ephraim, Machir (Manasseh), Zebulun and Naphtali joined the followers of Deborah and Barak. Reuben, Dan (at this time still on the seacoast) and Asher did not come.

In the battle fought at Taanach, near Megiddo, a tremendous rainstorm, interpreted by the Hebrews as an act of Yahweh, transformed the brook Kishon into a raging torrent. Canaanite chariots were trapped in the heavy mud and the tide of battle turned to favor Deborah and Barak. Meroz, an unknown group or location, is cursed for failure to help, and Jael, a Kenite woman, is blessed for the murder of the Canaanite general, Sisera, who sought sanctuary in her tent. As if death at the hand of a woman were not degrading enough, the singers added a taunt song, mocking the fruitless wait of Sisera’s mother. Her pitiful attempts to reassure herself of her son’s safety close the poem. The closing statement, a wish that all Yahweh’s enemies might suffer Sisera’s fate (v. 31), may have been added later.

A DYE VAT, NOW RESTING ON ITS SIDE, FROM TELL BEIT MIRSIM. The vat was carved out of a single block of limestone. The thread or cloth was dipped into the dye through the center opening and then the excess dye was carefully squeezed out and any run-off was caught in the outer trough and channeled back into the vat. The value placed on dyed cloth is evident from the remarks of Sisera’s mother (Judg. 5:30).

The theological convictions are clear. Yahweh was the god of a specific people. Their wars were his wars and Yahweh fought for his own. Others had their own gods and enjoyed a similar relationships. Social relationships are also revealed. Individual tribes were free to decide whether or not to participate in specific battles, but it was expected that they would rally when the war-cry was sounded. This, together with lack of reference to the tribes of Simeon, Judah and Gad and the listing of the people of Meroz as though they belonged to the tribal federation, raises questions about the patterns of relationship between the tribes. Were they really united by amphictyonic bonds? How many and what tribes settled the land? Does the amphictyonic pattern truly reflect eleventh-century relationships? For these questions there are no sure answers.

Read Judg. 4

The prose version of the battle differs in significant details. Only two tribes, Zebulun and Naphtali, participate in the battle, there is no condemnation of tribes not involved, and Sisera’s death is described differently. New details appear: the name of Deborah’s husband, Lappidoth, the strength of Canaanite forces and the mustering place of the Hebrews at Mount Tabor. Behind the prose account, there may be an ancient oral tradition, but specific details must be treated with caution.

Read Judg. 6-8

Two traditions lie behind the story of Gideon, one using the name Gideon for the hero, the other using Jerubbaal. Just as the Hebrews had swarmed into the land held by the Canaanites, so desert people – Midianites, Amalakites, and people of the east – came with their camels24 and possessions, threatening Hebrew holdings. Two etymological legends open the account, one explaining how the name “Yahweh-Shalom” (Yahweh is peace) came to be given to a spot in Ophrah (location unknown) and one explaining how the names Jerubbaal (Ba’al fights) and Gideon (the smiter) could represent the same individuals Gideon, a shrewd warrior, experienced divine possession; unwilling to rely upon this alone he put Yahweh’s promise of assistance to a material test. With a small band of warriors chosen for alertness and courage, he routed the enemy in a pre-dawn attack. The war-cry “A sword for Yahweh and for Gideon” signified divine support and sanction for the holy war. During the pursuit of the fleeing enemy, tribesmen participated from Naphtali, Asher, Manasseh and even from the touchy Ephraimites who had to be appeased by flattery. When Gideon paused in his attempt to capture the fleeing Midianite rulers, Zebah and Zalmunnah, and sought food from the people of Succoth, the townsmen were uncertain of Gideon’s ability to capture the men and refused him, saying:

“Is the palm of Zebah and Zalmunnah in your hand that we should give bread to your army?”

This literal translation brings out a meaning that may reflect the custom of removing the hands of the slain to facilitate rapid tallying of the dead.26 Once the kings were captured, the Succothites experienced the vengeance of Gideon. Gideon’s grateful followers sought to make him king, but he chose a monetary reward.

Read Judg. 9

Abimelech, son of Jerubbaal (Gideon), was more ambitious than his father. By murdering his brothers, with the exception of Jotham, and thus eliminating any potential rivalry, he had himself proclaimed king at Shechem. Jotham’s evaluation of Abimilech’s regal ability is expressed in Jotham’s fable. Within three years, Abimelech’s rule was contested by the men of Shechem and Abimelech was killed. No Deuteronomic editing is found in this account, and it may be that it was added after the Deuteronomic work was completed. On the other hand, perhaps the moral in 9:56f. was enough to satisfy the Deuteronomists.

Read Judg. 10:1-5

Tola, an Issacharite judge from Ephraim, and Jair from Gilead are listed without reference to enemies or battles. Once again it has been surmised that these names were derived from special sources and added after the Deuteronomic editing.

Read Judg. 10:17-12:7

Two traditions are merged in the story of Jephthah, the Gileadite, one dealing with struggles against the Ammonites, and the other treating Moabite problems (11:12-28). Jephthah, the son of a harlot and a refugee with a warrior band, is elected leader of Gilead by people and elders in a time of crisis, a custom known in other Near Eastern cultures. Vows are recited before Yahweh at Mizpah in Gilead (location unknown), but only later is divine seizure mentioned (11:29), perhaps a note added by a later editor wishing to demonstrate Jephthah’s charismatic qualities. To insure Yahweh’s support, Jephthah promised to sacrifice whoever came out of his tent upon his victorious return, knowing full well that it would be someone of his family. Human sacrifice does not receive too much attention in the Bible but is noted at II Kings 3:27, suggesting that the custom prevailed for a long time. Sacrifices such as that promised by Jephthah usually came in moments of extreme desperation and were designed to rouse the deity to furious action.27

The ritual of bewailing of virginity that develops out of the death of Jephthah’s daughter is not mentioned elsewhere in the Bible, and the account of the sacrificial death of the young woman may be associated with a fertility ritual adopted into Hebrew religious practice (cf. Ezek. 8:14). Possibly it is an adaptation of a custom similar to Anat’s weeping for the dead Ba’al, which incorporates an Hebraic aetiological legend. The remaining portion of the Jephthah story reflects intertribal conflict and provides interesting insight into dialectical variations among the groups (12:6). Only in 12:7 does Jephthah finally receive the title “judge.”

Read Judg. 12:8-13:1

Three leaders are mentioned between the end of the Jephthah cycle and the introduction of the Samson stories. No information concerning the social or political situation is given, but with Samson the Philistine issue is introduced. Like many other heroes, Samson had a miraculous birth: his mother, hitherto barren, was informed by a divine messenger that she was to conceive,28 the child was to be a Nazirite, living under a vow of consecration.29 As a grown man, Samson’s particular gift was his superhuman strength, and the secret of his magnificent strength lay in his Nazirite relationships to Yahweh, symbolized by his long hair. When he revealed this secret to his Philistine bride, Delilah, he was betrayed to his enemies. Samson’s story is important for what it portrays of Hebrew-Philistine relationships. Despite the tendency to maintain separate national identities, there was intermarriage of the sadiqa type, in which the wife remained with her parents and the husband paid periodic visits.30 Rivalry between Hebrews and Philistines was keen and some skirmishes did occur, but there was no open warfare. It is interesting that no language problem appears to have existed; Hebrews and Philistines were able to communicate without difficulty.

Read Judg. 17-18

The story of Micah of Mount Ephraim follows. Having robbed his mother, in terror of the curse she uttered against the thief, he confessed his crime and was forgiven. Part of the restored silver was utilized to make an image, or perhaps two images, for Micah’s house shrine. What was portrayed is not indicated, but apparently the shrine was dedicated to Yahweh. For a time, one of his sons served as priest, but a Levite from Bethlehem was later employed. The status of the Levite as one of the family of Judah is puzzling, for the term “Levite” may indicate a priestly order or a tribal relationship. Here the term appears to relate to the priestly function. When the tribe of Dan was compelled by the pressure of surrounding peoples (principally the Philistines) to abandon the land held along the seacoast and to migrate northward, the priest and the images were stolen from Micah and taken along with the Danites. The slaughter of the unsuspecting people of Laish and the occupation of their city by the Danites concludes the story. Micah of Ephraim, with his personal shrine, priest and images, perhaps gives some insight into individual family worship practices.

The lawlessness of the period (reflected in the intertribal hostility, justice by the imposition of the will of the stronger upon the weaker, and the continuing destruction and occupancy of Canaanite cities) is succinctly summarized by an editor: “In those days there was no king in Israel; every man did what was right in his own eyes.”

Read Judg. 19-21

A second story involving a Levite records the homosexuality of the men of Gibeah and the brutal sexual abuse and murder of the Levite’s concubine. The seizure of maidens during the vintage festival, a stratagem by which the Hebrews avoided the specifications of a hastily made vow, may reflect an annual ritual, which is here given an historical setting.

The period of the judges was a time of social, political and moral unrest. Law, which can only have significance if means of enforcement are available, appears to have been pretty much a hit-and-miss matter. The bonds uniting the Hebrew tribes are not clearly revealed: some situations evoked a co-operative spirit; others met with indifference or intertribal hostility. The newly won land was not held without difficulty: from without, Moabites and Ammonites pressed in; within the land were Canaanite citadels that had not been conquered; from the seacoast, the Philistines exerted expansive pressures eastward and northward. The socio-political structure of Hebrew society as reflected in the book of Judges simply could not cope with the situation. Something or someone had to unify the tribes, control the enemy, establish law and develop the nation. It was time for a king.

Endnotes

- A translation of the texts by H. L. Ginsberg appears in ANET. See also G. R. Driver, Canaanite Myths and Legends, Old Testament Studies, III (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1956); T. H. Gaster, Thespis; Cyrus H. Gordon, Ugaritic Literature (Roma: Pontificium Institutum Biblicum, 1949).

- Cf. Gaster, Thespis, pp. 3 ff.

- For a possible reference to a pre-Mosaic conquest of Shechem, cf. Gen. 48:22, and see G. E. Wright, Shechem, The Biography of a Biblical City (New York: McGrawHill Book Company, 1965), p. 20.

- In chapters 1-12, only 5:13-14, 9:6-7, and 10:12-13 are attributed to J, and most of the rest is taken to be a combination of D and E.

- The term herem comes from a root conveying the sense of separation and designates that which is set apart for holy purposes, devoted to the deity, or placed under a ban. Consequently, all living things were killed, all objects burnt, and metal items consecrated to the deity. Exceptions do occur, and at times the property becomes booty (cf. Josh. 6:18-21; 8:26 f.; 10:28, 35, 37, 39 f.). For the herem among Moabites, see the Moabite Stone, p. 167.

- Circumcision was widely practiced in the Near East and was an Egyptian as well as a Hebrew custom. In the earliest period, it may have been a puberty ritual by which the male youth was admitted to manhood. Among the Hebrews, it signified membership in the covenant community (cf. Gen. 17:11). Cf. “Circumcision in Egypt,” ANET, p. 326.

- K. Kenyon, Digging Up Jericho (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1957), pp. 256 ff.

- Compare Judg. 1: 10-15, 20 and Josh. 15:13-19; Judg. 1:21 and Josh. 15:63; Judg. 1:27-28 and Josh. 17:11-13; Judg. 1:29 and Josh. 6:10.

- W. O. E. Oesterley and T. H. Robinson, An Introduction to the Books of the Old Testament, Living Age Books (New York: Meridian Books, Inc., 1958), pp. 71-74.

- T. J. Meek, Hebrew Origins, chap. 1.

- M. Newman, op. cit., pp. 103-108.

- G. E. Wright, Biblical Archaeology, pp. 89 ff.

- E. Kraeling, Bible Atlas, p. 145.

- “Charismatic,” a term derived from the Greek charisma meaning “gift,” refers to the gift of divine power enabling the judges to accomplish what others could not do. References to specific acts of divine possession may have been added by editors.

- A possible chronology is outlined by J. Myers, “Judges,” The Interpreter’s Bible, 11, p. 682.

- Wright, Biblical Archaeology, pp. 89 ff.

- Previously reported in Josh. 24:29, and Judg. 1:1.

- John Bright, A History of Israel, pp. 156 f.

- Cf. Hab. 3:7; W. F. Albright, Archaeology and the Religion of Israel, p. 205, n. 419.

- Albright, loc. cit.

- Kraeling, op. cit., p. 150.

- Archaic Hebraisms, parallels to Canaanite poetry, interpretive additions by copyists are briefly discussed by Jacob Myers, “Exegesis of Judges,” The Interpreter’s Bible, II, 717 ff.

- Cf. references to Hebrews as “people of Yahweh” in vs. 11 with Num. 21:29 where Moabites are called “people of Chemosh.” As Yahweh fought for Israel so Chemosh fought for Moab (see ref. to Moabite Stone in Part Five).

- The camel had recently been domesticated and now, used in warfare by the invading Midianites, was tantamount to the introduction of a new weapon against which no adequate defense had been invented.

- Judg. 6:25-32 reflects a struggle against Ba’alism not found elsewhere in Judges.

- Note the removal of the heads of Midianite leaders as a proof of death (Judg. 7:25).

- Cf. II Kings 3:27.

- Judg. 13:2-14; cf. I Sam. 1; Matt. 1: 20; Luke 1: 11-13, 26-31.

- The root nzr means “to keep apart”; hence, a Nazirite is one set apart by a vow. Cf. Num. 6:1-21.

- Cf. W. R. Smith, Kinship and Marriage in Early Arabia, S. A. Cook (ed.) (London: A. & C. Black, 1903), pp. 93 f.

Old Testament Life and Literature is copyright © 1968, 1997 by Gerald A. Larue. All rights reserved.

The electronic version is copyright © 1997 by Internet Infidels with the written permission of Gerald A. Larue.