Old Testament Life and Literature (1968)

Gerald A. Larue

Chapter 27 – The Early Hellenistic Period

THE Hellenistic period in Palestine technically begins with the defeat of the Persian empire by Alexander the Great (334-323). Greek influence had entered the Persian world much earlier, for Greek mercenaries fought in Persian armies and Greek traders introduced wares and ideas from the Hellenistic world. The period terminates with the conquest of Palestine in 63 by Pompey, the Roman. Our discussion will be divided into two major parts:

- The Period of Hellenistic Rule.

- The Period of Jewish Independence.

THE PERIOD OF HELLENISTIC RULE

Artaxerxes III Ochus (358-338) became king of Persia upon the death of his father Artaxerxes II, and secured his regime through a blood purge. Potential rivals in the rather large family of Artaxerxes II were eliminated.1 Revolts in Phoenicia and Palestine, which may have involved Judah, were rudely put down. For ten years the port city of Sidon withstood Artaxerxes III before petitioning for peace, but Artaxerxes had the envoys murdered. It was clear to the Sidonians how Artaxerxes would treat them should they surrender and, rather than suffer the barbarous cruelties of the Persians, the Sidonians fired their city and thousands perished in the holocaust.2 According to Josephus ( Antiquities 11:7:1), Judah also experienced Artaxerxes’ anger. Heavy fines were imposed and the temple was profaned. By 342, Artaxerxes had invaded Egypt to end that country’s brief period of independence.

Artaxerxes was murdered by his son Arses (338-336), and Arses died by poison soon afterward. In 336, Darius III Codomannus (336-331) was crowned king, and in this same year Philip of Macedon, who had attempted to unify the Greeks, was murdered. Philip’s twenty-year old son, Alexander, who was to be called "the Great," became king and almost immediately was embroiled in the Persian-Greek power struggle which had begun in Philip’s time.

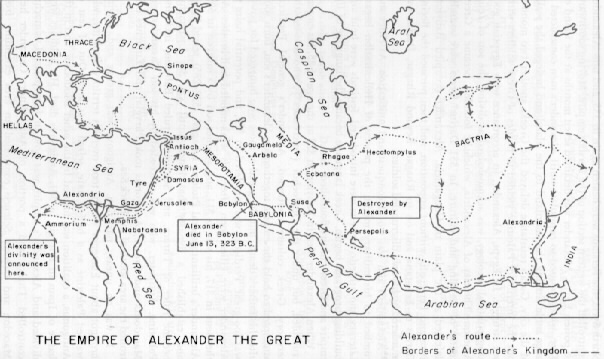

The conquest of Persia was rapid. In 334, Alexander crossed the Hellespont and defeated Darius at the Granicus River. At Issus in North Syria, the Persians were beaten again in 333, and now Alexander controlled the western section of the Persian empire. Moving southward to possess Egypt, Alexander was detained seven months at the island of Tyre, which refused to capitulate until Alexander’s men constructed a huge mole linking the mainland to the island and besieged the walls of the city. Gaza’s resistance delayed the Greeks another two months, but the interior of Palestine yielded to hordes of Greek soldiers without struggle. In Egypt, Alexander, in accordance with Egyptian god-king political theology, was acknowledged as divine, the son of Zeus-Ammon. The city of Alexandria, which he founded, became a Greek center of learning and culture. In 331 Darius’ forces were soundly defeated at the plain of Gaugamela. Alexander occupied Babylon, Susa and Persepolis without opposition, and then pursued the fleeing Darius to Ecbatana and on to Rhagae. Beyond Rhagae, Darius was murdered by his own disgruntled soldiers.

Alexander’s aim was world conquest and unification. As cities succumbed to his military might, the process of Hellenization began. Literary and athletic contests were introduced, festivals were held and building programs begun. Greek language became the language of the empire and Greek culture flourished.

When Alexander died in Babylon in 323 at the age of 33, his empire crumbled, but under the Diodochoi ("successors"), who divided the territory, Greek culture continued. Alexander’s general Perdiccas attempted to hold the empire together for Alexander’s son, born soon after his father’s death, but the greed of those who hungered for power was too great. Perdiccas was murdered in 321, and potential heirs to Alexander were killed soon after: his weak-minded half-brother Arrhedaeus in 317, his son in 311, and another son by a mistress in 309. Alexander’s brilliant general Ptolemy I Lagos3 (322-285) seized Egypt and established a dynasty that lasted until A.D. 30. Lysimachus became ruler of Thrace, and Seleucis I ruled Babylon, including Palestine. Antipater, who was succeeded by his son Cassander, got Macedonia and Greece; Antigonus took Phrygia; and Eumenes controlled the area south of the Black Sea.

it was an uneasy partition. Antigonus was greedy and, having brought about Eumenes’ death, took over his territory. Ptolemy, who wanted Palestine as a buffer state, seized that area. Out of fear of Antigonus, a coalition was formed by the other Diodochoi, and in the battle of Ipsus in Phrygia in 301, Antigonus died. His holdings were divided and Alexander’s empire was now in four parts: Lysimachus controlled Thrace and a portion of Asia Minor; Cassander held Macedon and Greece; Seleucis controlled an area extending from northern Palestine to the Indus River; and Ptolemy ruled over Egypt and central and southern Palestine.

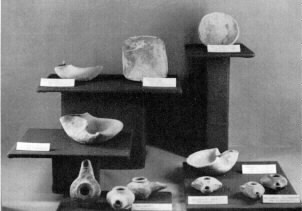

PALESTINIAN HISTORY IN LAMPS. A sketch of the history of Palestine can be told with lamps recovered from excavations. The lamp in the upper right is from the Early Bronze Age and is simply a saucer in which oil (olive or animal) was poured and a wick, possibly of flax, was draped over the edge and set alight. Later, in the early part of the Middle Bronze Age the saucer was squared and wicks were laid in the corners of the dish. By the time of the Hyksos the saucer was folded inward on one side to form a channel for the wick, and by the time of the Hebrew invasion it had become the custom to elevate the spout and give the saucer a slight base (lamp in third tier) . The Hebrews adopted this lamp but began to thicken the base (lamp at the rear on the bottom right platform) . The six lamps in the foreground are from the Hellenistic period. The three on the left were made on a wheel and the spout was added. The three on the right (Delphiniform lamps) were made in two halves in molds and then brought together and sealed at the seam. By the Hellenistic period the open saucer lamps had been abandoned in favor of the closed lamp with a central opening through which oil was poured into the lamp and a spout in which the wick was placed.

PALESTINIAN HISTORY IN LAMPS. A sketch of the history of Palestine can be told with lamps recovered from excavations. The lamp in the upper right is from the Early Bronze Age and is simply a saucer in which oil (olive or animal) was poured and a wick, possibly of flax, was draped over the edge and set alight. Later, in the early part of the Middle Bronze Age the saucer was squared and wicks were laid in the corners of the dish. By the time of the Hyksos the saucer was folded inward on one side to form a channel for the wick, and by the time of the Hebrew invasion it had become the custom to elevate the spout and give the saucer a slight base (lamp in third tier) . The Hebrews adopted this lamp but began to thicken the base (lamp at the rear on the bottom right platform) . The six lamps in the foreground are from the Hellenistic period. The three on the left were made on a wheel and the spout was added. The three on the right (Delphiniform lamps) were made in two halves in molds and then brought together and sealed at the seam. By the Hellenistic period the open saucer lamps had been abandoned in favor of the closed lamp with a central opening through which oil was poured into the lamp and a spout in which the wick was placed.

Palestine, the buffer state between Seleucis and Ptolemy, was to shuttle between Syria and Egypt. During the period of Egyptian control, a Jewish colony was established in Alexandria, which under Ptolemy I was becoming one of the greatest cultural and educational centers of the ancient world. Taxes in Judah were heavy, but the Jewish high priest was governor.

Ptolemy I was succeeded by Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285-246). The history of the Jews in this period is anything but clear, but it was under this monarch that the LXX was begun. During the reigns of Ptolemy II and Ptolemy III Euergetes (246-221), Egypt was strong financially and militarily. What burdens were placed upon the Jews in Palestine are not known, but perhaps the efforts of Ptolemy III to seize and hold parts of northern Palestine that had been under Seleucid control tended to make Palestine a military state subject to Near Eastern wartime controls. With Ptolemy IV Philopator (221-204), Egyptian strength waned, although he was able to defeat the Seleucids at Raphia. When he died, his five-year-old son Ptolemy V was in no position to give adequate leadership for control of Palestine.

The Seleucid empire was now ruled by Antiochus III (223-187) who, like many before him, was called "the Great." Antiochus defeated Ptolemy at Gaza in 200 and again at Paneus in 198, and Palestine came under Seleucid control. Many Jews welcomed Antiochus as a deliverer. Antiochus, for his part, appears to have treated the Jews with respect, showing consideration for their religious traditions despite his enthusiasm for Greek culture, an enthusiasm shared by the strong pro-Greek party that had risen among the Jews.

In 187 Antiochus died. He had been defeated by Rome in the battle of Maknesia in 190 and had burdened his people with heavy taxation necessary to pay the indemnity demanded by Rome. The debt was inherited by his son Seleucis IV (187-175) who appointed a certain Heliodorus as collector. When Seleucis was murdered by Heliodorus, Antiochus IV (175-164) became king.

It is almost impossible to evaluate the significance of Antiochus IV from Jewish sources, so bitterly did Jewish writers react to him. He assumed the name "Epiphanes," which may be translated "the illustrious" or "the revealer" or "the revealed one." The Jews called him "Epimanes," which means "the cracked one" or "the mad one," so vigorously did he pursue the policy of Hellenization and so often did he violate Jewish sensitivities. Antiochus was an activist, determined to redeem the loss of military, economic and territorial prestige and power. His capital city, Antioch in Syria, was enlarged to accommodate Greeks seeking freedom from the growing pressures of Rome. A large community of Jews also lived there. New buildings were erected, new business was encouraged and Antioch became a center of commerce, wealth and culture. To strengthen political, religious and societal bonds, Antiochus encouraged Hellenic religion and culture, and it was at this point that he came into violent conflict with the separatist attitudes of the anti-Greek Jews of Judah. To meet the expenses of his program he laid heavy taxes upon his subjects.

Onias III the Jewish high priest, was pro-Egyptian. When Antiochus became king, Onias retired to Leontopolis, Egypt, to found a Jewish colony. Antiochus sold the high priest’s office to the highest bidder and Joshua, who preferred the Greek form of his name, "Jason," bought the post. Now the pro-Syrian, pro-Hellenistic Jason entered into a conspiracy with Antiochus to bring the Jews into conformity with Greek culture. Greek garb and food were common. A gymnasium was built in Jerusalem and young men attended, including priests who left their altar duties for discus throwing and other athletics. Many gymnasium activities were performed in the nude, and some Jews underwent surgery to remove the distinguishing mark of circumcision-an act which, to the orthodox, was tantamount to rejection of the covenant.4

In 171, a certain Menelaus offered more money for the high priesthood and Antiochus accepted. Jason fled to Transjordan and Menelaus robbed the temple treasury to pay his debt to the king. Now a new sect of Jews was formed from scribes and their followers, and these took the name "Hasidim," which means "pious" but which implies "loyalty." The Hasidim concentrated on the study of the Torah and observance of the Law, and when their religious customs were proscribed were among those who went passively to their death, rather than resist.

War broke out between Syria and Egypt, and Antiochus marched against his enemies in 170. His plans for conquest failed and a rumor arose that Antiochus had been killed in battle, prompting Jason to return from exile. But Antiochus was not dead. On his return from Egypt, he quelled a revolt inspired by Jason and looted the temple. A Phrygian named Philip was appointed governor of the Jews. In 168, Antiochus returned, for Jewish nationalistic pressures had not diminished. This time Jerusalem was burned and its walls demolished. Thousands died in battle and many others were enslaved. Every expression of Judaism was proscribed, including Sabbath worship, Torah study and circumcision, and the most excruciating punishments were devised for violators. Worst of all, on December 15, 168, an altar to the Olympian Zeus was built upon the Jewish altar of sacrifice and pigs’ flesh was sacrificed. All Jewish temple worship ceased for this was "the abomination that made desolate" as the writer of the book of Daniel was to describe the act that contaminated the holy altar. The situation had become intolerable for the faithful Jews and, as we shall see, they were faced with a choice: succumb or do battle.

ESTHER

Read Esther

The book of Esther is a secular legend with its setting in Susa, the Persian capital. The story may have originated during the Persian period, although it probably was not reduced to the form in which we know it until the beginning of the Hellenistic era. Some scholars have attempted to discover references to Babylonian deities and rituals in the book, identifying Mordecai with Marduk, Esther with Ishtar, and other characters with minor, obscure deities.5 Others have tried to relate the writing to Assyrian springtime rites, to Persian New Year observances,6 to Greek wine festivals, to historical events such as the victory of the Jews over Nicanor in 161, or to other historical or cultic themes.

That Esther is not history, despite some accurate details about Persian government (cf. 1:14; 3:7), is clear from the numerous inconsistencies and exaggerations. Ahasuerus is usually identified as Xerxes (Khshayarsha), who reigned between 485 and 465. A Persian administrator named Marduka (Mordecai) is known from this period, but there is no indication that he was a Jew, although some Jewish parents did give their children the name Mordecai, which honored the chief god of Babylon (cf. Ezra 2:2; Neh. 7:7). According to the Greek historian Herodotus, a contemporary, Xerxes’ wife was Amestris, not Vashti or Esther. Nor do these names appear as the wives of other Persian monarchs. However, if Xerxes, like Artaxerxes II, had a concubine for each day of the year, Vashti or Esther may have been among them. Mordecai is supposed to have been one of the Jews that went into exile under Nebuchadrczzar, which would make him well over 100 years old when appointed to the court (2:5 f.). The extermination of 75,000 people by the Jews with Xerxes’ permission seems unlikely (9:16). Certain exaggerations are so extreme that they must have been included to delight the audience. For example, the gallows are 50 cubits or about 75 feet high! Haman estimates he could raise 10,000 talents or about $18,000,000 by confiscating Jewish property-a sum estimated at more than one half of the annual income of the Persian empire. It seems best to recognize the story as a legend embodying, as most legends do, some accurate historical details.

The earliest references to the book of Esther are found in Contra Apion 1:8, the work of the Jewish historian, Josephus (A.D. 1). Josephus drew upon the LXX version of Esther, which includes the "additions to Esther" that we will consider later. The omission of any reference to Esther in the second century work known as Ecclesiasticus or Sirach, written by Jesus ben Sira, in which Jewish heroes are extolled, has led some scholars to date Esther after this time. Arguments from silence are never very convincing.

The tendency of the writer of Esther to refer to the events of the story as taking place in the distant past (1:1, 13; 10:2) and the expanded explanations (4:11; 8:8) suggest a time of recording long after the events described. The reference to the dispersed Jews best fits the Greek period (3:8). On the basis of this limited evidence, it would appear that the story was written in the early Greek period, a time when stories about Jewish successes in Persian royal circles would suffer least contradiction and a time when the spirit of Jewish independence appears to have been strong.

The book is completely secular7 and contains no reference to the deity. It exalts a Jewish heroine who saves the people from persecution, and it delights in Jewish success and victory over the enemy. The writer possessed genuine narrative skill and developed his theme through a succession of dramatic climaxes, alternating tension with delightful humorous touches (cf. 1:21-22; 3:9; etc.). But the story is more than entertainment. It is a grim reminder to a people buffeted by great powers of the ever-present potential of persecution by a tyrant-not necessarily the king, but rather the power-hungry, attention-loving, minor official whose pomposity was so easily threatened by the non-conformist or the man of conviction. In the magnificent characterizations, the author provided his readers with a response to tyranny and oppression and exposed the transparent motives of theoppressor, and exalted the individual who remained faithful to his commitments and to himself. Later the book of Esther was linked to the festival of Purim.

JOEL

Read Joel

Joel is the work of an unknown prophet who conveys to his readers through dramatic imagery the immediacy of a frightful threat to national well-being, and the subsequent deliverance. The mood in the three chapters moves from concern, through terror, to desperate repentance and hope, to relief at salvation and exalted hopes for the future. The work appears to be a literary unity, the work of one writer. Because of the emphasis on Jerusalem and Judah, the author is, obviously, a Judaean.

At one time Joel was listed among the earliest prophetic writings, but this view has been abandoned. The text lacks themes prominent in eighth century prophetic books: kings, Canaanite religion, idolatry, apostasy. Nor are there references to Assyrians, Babylonians or Persians. The specific mention of the Greeks (3:6) and the indication that the temple is standing and the cult operating (1:9, 13, 16; 2:17) points to the early Hellenistic period. The imminent destruction of Tyre, Sidon and Philistia reflected in 3:4-8 suggests that Joel may have been written after Alexander the Great had begun the siege of Tyre.

The opening verses describe a plague of locusts sweeping over the land. It is usually assumed that subsequent passages describing the devastation of the land reflect the destructive activities of these insects. Such terms as "nation" in 1:6, "a great and powerful people" in 2:2 and the descriptions of the approaching hordes (2:4 ff.) are interpreted as symbols for the swarming locusts. But, if Joel is writing when Alexander’s armies are moving through Palestine, it is possible that he is describing Greek armies. The initial swarm of locusts was, as in Amos, actually seen, but in the prophet’s imagery the insects were symbolic of the waves of Greeks marching through the land. References to "the nation" and "the great and powerful people" were, therefore, historical. On this basis the book may be analyzed as follows:

1:1 The editorial superscription.

1:2-4 The initial vision of the swarm of locusts in which different kinds or stages of development of locusts are indicated.

1:5-14 The call to lamentation rites for the wasting of the land and the blending of locust imagery into a description of the invading enemy.

1:15-2:11 The interpretation of events as forewarnings of the Day of Yahweh, which is depicted as a day of gloom and destruction.

2:12-17 The nation is summoned to repentance rites in the hope that Yahweh will deliver the people.

2:18-29 Yahweh has saved his people. The Greeks did not destroy or plunder. There is promise of ample harvest and abundant blessing.

2:30-32 The second vision of the Day of Yahweh, now described as a day of salvation, blessing and restoration for the Jews and Judah.

3:1-3 The promise of judgment against Judah’s oppressors.

3:4-8 The implication of the imminent fall of Tyre, Sidon and Philistia.

3:9-21 The third vision of the Day of Yahweh as a time of judgment for the people of the world, and a time of blessing for Judah.

Because a majority of scholars assume that the locusts represent a real plague8 and that there is no reference to foreign invaders, the following analysis is provided:

1:1 The editorial superscription.

1:2-20 The plague of locusts and a drought.

2:1:11 The locusts as a warning of the Day of Yahweh.

2:12-17 The call for repentance.

2:18-27 The restoration of the land.

2:28-32 The signs of the Day of Yahweh.

3:1-16 Judgment on the nations.

3:17-21 Blessings on Judah.

For Joel, the locusts (or the Greeks) are signs of Yahweh’s anger, and although there is no specification of evils, the nation is called to repent. As the danger passed, the penitential mood changed to thanksgiving. The concluding visions of the Day of Yahweh are quite distinct from the first (cf. 2:30-32; 3:9-21; and 1:5-2:11). In the first vision, judgment falls on Judah and the prospects are grim; in the last visions condemnation and threats are directed against Judah’s enemies and hopes for the Jews are high. Clearly, the day of Yahweh concept was still strong in the Jewish community, and particularistic and nationalistic dreams for the future were undiminished. The last two visions of Yahweh’s Day have an air of finality, as though the history of struggle for identity and the long hoped for period of blessing were to be realized. Once "that Day" had come, the future would be secure. This eschatological hope or idealistic doctrine of the end was soon to expand and develop new facets. The book reflects a liturgical framework which may have grown out of the close working relationship between the prophets and the cult.9

DEUTERO-ZECHARIAH

The second section of the book of Zechariah consists of two separate collections of oracles that defy precise dating: Chapters 9 to 11 and Chapters 12 to 14. At one time both collections were attributed to Jeremiah because in the New Testament the Gospel of Matthew (27:9-16) quotes part of Zechariah 11:12 f. and attributes the words to Jeremiah. Some scholars have argued for pre-Exilic dates. The first collection refers to both Judah and Ephraim and speaks of Egypt and Assyria, and it was assumed that the oracles must have come from the period of the divided Hebrew kingdoms. Chapters 12 to 14 were dated between 609 and 598, for they imply that Jerusalem was still standing but that Josiah, to whom it was assumed that 12:11 referred was dead.10 Most present-day scholarship places the time of writing in the early years of the Hellenistic period, although later dates have been proposed. The first eight verses are interpreted as a record of Alexander’s campaign in Syria and Palestine in 332, and specific reference to the ramp built by Alexander’s men in the siege of Tyre is found in 9:3 f. Furthermore, Greece is specifically mentioned in 9:13. We will accept the Hellenistic period as the time of writing but with reservations, for the evidence upon which the dating rests is far from conclusive.

Read Zech. Ch. 9

The opening verses of the first collection pronounce judgment on Judah’s neighbors: Aram or Syria with the cities of Hadrach, Damascus and Hamath; Phoenicia with Tyre and Sidon; and Philistia with four of the five confederated cities (Gath is omitted). Alexander’s campaign had begun and the prophet interpreted the military activities of the Greeks as Yahweh’s judgment and as a sign that the great Day of Yahweh was at hand. He envisioned the triumphant, victorious, messianic king entering the city of Jerusalem riding upon an ass, as Solomon had done after his coronation. So great was the royal authority that peace was established by fiat. Subsequent events include the release of captive Jews, the supremacy of the Jews over the Greeks and a dramatic theophany of Yahweh as the god of war protecting and exalting his people.

Read Ch. 10

The two opening verses of Chapter 10 form an independent oracle condemning those who, in time of drought, sought aid from idols. The remaining verses appear to be from the early years of the Diodochoi, who are condemned as "shepherds." The restoration of the Jewish nation is predicted.

Read Ch. 11

The first verses of Chapter 11 appear to refer to the fall of the Diodochoi, but the remaining enigmatic verses provide no clue for intelligent interpretation.

Read Chs. 12 to 14

The second section, sometimes referred to as Trito-Zechariah, may also have been composed in the time of the Diodochoi. Yahweh’s miraculous intervention, the defeat of Judah’s oppressors and the establishment of the ideal kingdom, are foretold. Perhaps something of the low degree to which prophecy had sunk is implied in 13:4-6. The writer foretells a period of darkness for Yahweh’s people after which the new kingdom will be established. The closing verses portray the pilgrims streaming toward Jerusalem for the New Year festival, and the worshipers include foreigners who recognize Yahweh as the supreme and only deity. Those who fail to come do not enjoy divine blessing.

Endnotes

- Artaxerxes II had three sons by his queen Stateira and 115 by the 360 concubines officially assigned to him (one for each day of the civil year). Cf. A. T. Olmstead, History of the Persian Empire (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1948), P. 424, now issued as a Phoenix paperback.

- Ibid., pp. 436 f.

- He was also called "Soter" (Savior).

- The bulk of this information is drawn from I Maccabees, chap. 1.

- For a detailed discussion, cf. N. S. Doniach, Purim and the Feast of Esther (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1933), pp. 1-53.

- For a strong defense of this hypothesis, cf. T. H. Gaster, Purim and Hanukkah (New York: Henry Schuman, 1950), pp. 12-18.

- However, see the "Additions to Esther."

- J. A. Thompson, "The Book of Joel," The Interpreter’s Bible, VI,. 733 f., and "Joel’s Locusts in the Light of Near East Parallels," Journal of Near Eastern Studies, XIV (1955), 52-55.

- Cf. T. H. Gaster, Thespis, pp. 44 ff.

- For a different analysis, cf. Benedikt Otzen, Studien über Deuterosacharja, Acta Theologica Danica, VI (1964). Otzen dates chaps. 9 and 10 after Josiah’s reign; chaps. 10, 11 and 12, which he finds to be Deuteronomic, in the period immediately preceding the Exile and in the earliest years of the Exile; and chap. 14 in the late post-Exilic period.

Old Testament Life and Literature is copyright © 1968, 1997 by Gerald A. Larue. All rights reserved.

The electronic version is copyright © 1997 by Internet Infidels with the written permission of Gerald A. Larue.