Old Testament Life and Literature (1968)

Gerald A. Larue

Chaper 6 -The People, from the Paleolithic to the Chalcolithic Periods

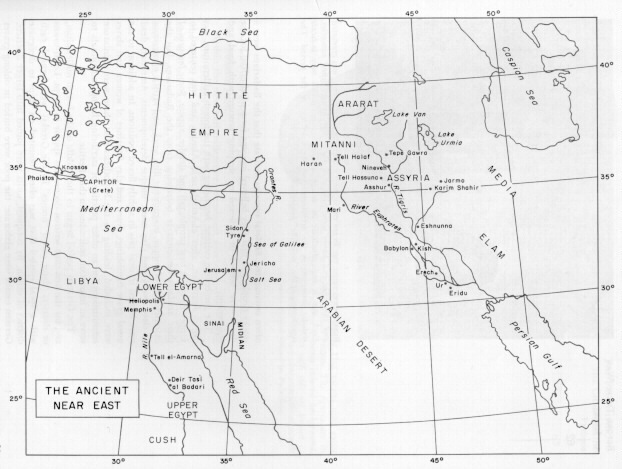

OUR study will concentrate on the biblical period which embraces less than two millennia of human history, but long before the Hebrews entered the historical scene there were people living in the Fertile Crescent and Egypt. To grasp the magnificent human heritage that fell to the Hebrews and those who lived during the biblical period, the next two chapters will provide an overview of ancient Near Eastern history as reconstructed out of the researches of historians and archaeologists, first, from the Paleolithic to the Chalcolithic periods; and next, from the Early Bronze to the Late Bronze periods.

As elsewhere in the Near East, evidence of human habitation can be found in Palestine dating to the Paleolithic period, or Old Stone Age, which lasted hundreds of thousands of years.1 Paleolithic man was a nomad, depending upon natural resources for sustenance, following migrations of wild animals and harvesting wild grain wherever it chanced to grow. Possibly his itineraries followed some generally established pattern, terminating in a periodic return to a family cave. On the basis of stone artifacts (implements made from wood, fibre or leather are seldom preserved), the earliest Paleolithic period, which extends from more than 300,000 years ago to approximately 70,000 years ago, can be divided into three parts.

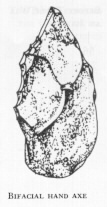

During the so-called "Pebble" or "Chopper" period, water-smoothed pebbles or chunks of rock were roughly shaped by chipping one end into a cutting edge. Such tools have been found in the Jordan River valley just south of the Sea of Galilee and at a hillside site midway between Tiberias and Nazareth. In the later Bifacial period, hand-axes were formed by working both sides of a flint block to make a point or cutting edge, and such tools have been found in Galilee, near Jerusalem, and in the desert regions in southern Palestine. Hearths and burned bones reveal that man had mastered the use of fire (approximately 200,000 years ago), and circles of stones, which may have served as seats, spaced around the fire suggest that the glowing embers provided a center for family gatherings.2

During the so-called "Pebble" or "Chopper" period, water-smoothed pebbles or chunks of rock were roughly shaped by chipping one end into a cutting edge. Such tools have been found in the Jordan River valley just south of the Sea of Galilee and at a hillside site midway between Tiberias and Nazareth. In the later Bifacial period, hand-axes were formed by working both sides of a flint block to make a point or cutting edge, and such tools have been found in Galilee, near Jerusalem, and in the desert regions in southern Palestine. Hearths and burned bones reveal that man had mastered the use of fire (approximately 200,000 years ago), and circles of stones, which may have served as seats, spaced around the fire suggest that the glowing embers provided a center for family gatherings.2

|

CHART IV

|

||||

|

Years B.C.

|

Archaelogical Period

|

Culteral Features

|

Specific Locations

|

|

|

300,000 to 70,000

|

Lower Paleolithic

|

Nomadic Life

|

Pebble tools Man discovers fire (200,000) Bifacial tools |

Tabunian Cave on Mount Carmel; Yarbrud in Syria |

|

70,000 to 35,000

|

Middle Paleolithic

|

Nomadic Life

|

Mousterian flaked flints Neanderthal Man |

Galilee, Palestine; Mount Carmel, Palestine |

|

35,000 to 12,000

|

Upper Paleolithic

|

Nomadic Life

|

Blade industries "tepee" type dwellings, figurines, bone and ivory jewelry |

Wadi en-Natuf, Palestine; Shanidar, Iraq; Zawi Chemi, Iraq; Karim Shahir, Iraq |

|

12,000 to 10,000

|

Mesolithic

|

Hamlet Life

|

Natufian micro-flints, new weapons and tools, primitive agriculture, rock drawings and wall paintings, beginnings of sea travel | Wadi en-Natuf, Palestine; Deir Tasi, Egypt; Jarmo, Iraq; Tell Hassuna, Iraq |

|

10,000 to 4,500

|

Neolithic

|

Village Life

|

Extensive agriculture, domestication of animals, extensive trade, early shrines | Jericho, Palestine; Deir Tasi, Egypt; Jarmo, Iraq; Tell Hassuna, Iraq |

|

4,500 to 3,300

|

Chalcolithic

|

Citys/States and Kingdoms

|

Copper and stone tools, pottery of varied styles, beginning of ziggurats, development of writing and mathematics, cylinder seals used, time of the "Flood", Egyptian nomes unite to form upper and lower Egypt | al Badari, Egypt; el Amrah, Egypt; Tepe Gawra, Iraq; Tell Halaf, Iraq; Eridu, Iraq; Beer-sheba, Palestine; Dead Sea Region |

The third period, named Tabunian after the Tabun cave on Mount Carmel, and Yabrudian after a site in Syria, is characterized by superior skill in shaping tools and by new and more varied implements. Variances in tool patterns at different sites (as at Carmel and Yabrud) indicate that each group created and maintained local traditions and techniques. Comparable materials are found in Europe.

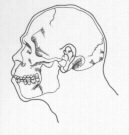

In the Middle Paleolithic period, extending from about 70,000 to 35,000 years ago, man’s tools improved. Having learned to take thinner flakes from flints, he could make more precise shapes and a greater variety of implements were developed. The people of this culture, first discovered at Le Moustier in France and named Mousterian, are related to Neanderthal man and are similar to (but still different from) modern man. In 1923, Mr. F. Turville-Petre, an Oxford student, excavating a cave near the Sea of Galilee on behalf of the British School of Archaeology, discovered four pieces of the skull of a young man amid mineralized animal bones and flint tools of the Mousterian type. This find, labeled "Galilee man," was the first of such discoveries in Palestine. "Carmel man," whose remains were found shortly afterward in caves in the Carmel mountains, proved to be another offshoot of Neanderthal man. Taller than Neanderthal, walking upright, probably possessing speech, Carmel man left flint tools, bone ware, an amazingly preserved four-sided spear point of wood, and numerous burials which, by their very nature, reflected deep concern for the dead and perhaps the expression of some form of religious feeling. The dead were entombed in the floor of the cave, sharing in death the same habitation as the living. Bodies were placed on the side in the "sleep" position and there is some evidence that food was interred with the body, suggesting belief in afterlife.

In the Middle Paleolithic period, extending from about 70,000 to 35,000 years ago, man’s tools improved. Having learned to take thinner flakes from flints, he could make more precise shapes and a greater variety of implements were developed. The people of this culture, first discovered at Le Moustier in France and named Mousterian, are related to Neanderthal man and are similar to (but still different from) modern man. In 1923, Mr. F. Turville-Petre, an Oxford student, excavating a cave near the Sea of Galilee on behalf of the British School of Archaeology, discovered four pieces of the skull of a young man amid mineralized animal bones and flint tools of the Mousterian type. This find, labeled "Galilee man," was the first of such discoveries in Palestine. "Carmel man," whose remains were found shortly afterward in caves in the Carmel mountains, proved to be another offshoot of Neanderthal man. Taller than Neanderthal, walking upright, probably possessing speech, Carmel man left flint tools, bone ware, an amazingly preserved four-sided spear point of wood, and numerous burials which, by their very nature, reflected deep concern for the dead and perhaps the expression of some form of religious feeling. The dead were entombed in the floor of the cave, sharing in death the same habitation as the living. Bodies were placed on the side in the "sleep" position and there is some evidence that food was interred with the body, suggesting belief in afterlife.

CARMEL MAN differed from the typical Neanderthal type found in Europe and had physical characteristics closer to Homo sapiens. The thick ridge of the brows or occipital protuberances, the heavy nasal structure and the lack of any true chin development are typical Neanderthal features. Carmel man shows the slightest hint of a developing chin and above the protruding brows is a higher forehead, more akin to Homo sapiens. This sketch is after E. Anati in Palestine Before the Hebrews (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1963) p. 103.

CARMEL MAN differed from the typical Neanderthal type found in Europe and had physical characteristics closer to Homo sapiens. The thick ridge of the brows or occipital protuberances, the heavy nasal structure and the lack of any true chin development are typical Neanderthal features. Carmel man shows the slightest hint of a developing chin and above the protruding brows is a higher forehead, more akin to Homo sapiens. This sketch is after E. Anati in Palestine Before the Hebrews (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1963) p. 103.

The final stage of the Paleolithic period, the Late or Upper Paleolithic which extended from about 35,000 to between 10,000 and 15,000 years ago, has provided the earliest evidence of man-built structures. Small mounds of earth and rock or excavations into the earth provided the outline of the dwelling above which walls and a roof were constructed, possibly out of branches or perhaps out of animal skins, after the fashion of the American Indian tepee. It is possible that these structures were occupied for part of the year, and in inclement weather Upper Paleolithic man returned to his cave. Well-made flint tools, carved ivory, pendants, necklaces and bracelets of shells, bone, ivory and stone testify to the creative skill of these people. Carved figurines of pregnant females may represent amulets used to facilitate childbirth, or, in view of the later development of the worship of the mother goddess, they may be early evidence of the beginnings of this cult. Comparable Paleolithic evidence has been found in Egypt where Bifacial and Mousterian artifacts were recovered on terraces overlooking the Nile, at oases, and on the shores of ancient lakes.

Sometime between 14,000 and 12,000 years ago, the Mesolithic period or Middle Stone Age began in the Near East, and with it came a veritable social and technological revolution probably due, in part, to changes in climate at the close of the last Ice Age. The most dramatic evidence in Palestine has come from a site ten miles northwest of Jerusalem in the Wadi en-Natuf, which has given the name "Natufian" to the culture. In 1928, in a huge cave some 70 feet above the wadi, Miss Dorothy Garrod found evidence of a center of flint industry characterized by tiny crescents and triangles of flint known as micro-flints. Natufian sites, since found in other locations, suggest long periods of uninterrupted occupation and reveal a uniformity in art, industry, burial customs and artifacts that indicates close communication among groups, although it must be admitted that each site has its own distinctive features. Massive implements, such as huge basalt mortars weighing hundreds of pounds for grinding grain, were produced, as well as such delicate objects of bone as fish hooks, barbed harpoons and pins. A wide variety of tools, including adzes, sickles and picks, suggest the beginning of agriculture. Rock carvings portray men using lassoes and nets, and the imprint of matting on clay floors indicates the weaving of fibers.

During this period the bow and arrow were used and, with better tools and weapons and having learned how to store food, it is possible that life became somewhat easier, providing time for artistic expression. Rock drawings and wall paintings depict men and animals with the precise pictorial representation so often characteristic of primitive art, but Natufian man moved beyond this phase into schematic and symbolic representation and geometric patterns. Skeletons were often decorated with necklaces, pendants, breast ornaments and headdresses of shell and bone. The curious custom of separating the skull from the rest of the skeleton has been variously interpreted as a cannibalistic rite, evidence of ancestor worship, a skull cult, or simply as an interesting hobby of collecting tokens of victory over enemies. Sea travel had begun, probably on rafts of bamboo or papyrus at first and later on more sophisticated ships, and the Near Eastern world was drawn more closely together.

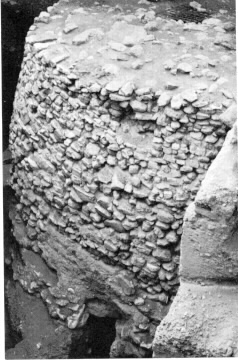

The Neolithic or New Stone Age began between 12,000 and 10,000 years ago (10,000-8,000 B.C.) and is characterized by settled communities in which man, having developed agricultural skills, was no longer dependent upon natural resources for food. Excavations at Jericho, directed by Miss Kathleen Kenyon, produced impressive evidence of the development of village culture prior to the invention of pottery. Floors surrounded by stone and earth humps were found in the earliest levels, but solid structures soon began to appear. Circular houses, with pounded earth floors cut below the level of the surrounding terrain, had upper walls of upright poles and elongated, cigar shaped bricks sloping inward to form domed roofs. Woven reed mats covered the floors. Around this community, a wall of free-standing stone had been built, over six feet wide in some places and still standing to a height of twelve feet. A huge tower more than thirty feet high with an interior staircase was built against the inner wall. Such structures indicate the existence of fully developed, cooperative community life as early as the sixth and seventh millennium B.C.

THE NEOLITHIC TOWER AT JERICHO. The steel grating at the top covers the opening to a narrow inner staircase that winds to the entrance at the bottom.

THE NEOLITHIC TOWER AT JERICHO. The steel grating at the top covers the opening to a narrow inner staircase that winds to the entrance at the bottom.

Subsequent layers of occupation reveal new living patterns. Houses become rectilinear with plastered floors and walls. Bones of goats, pigs, sheep and cattle point to domestication of these animals. Obsidian, turquoise and cowrie shells were imported from Syria, the Sinai peninsula and the Mediterranean for manufacture of tools and ornaments. In a shrine, a piece of volcanic stone from the Dead Sea area was placed in a niche, perhaps foreshadowing the sacred standing pillars mentioned in the Bible.3 Clay figurines and human skulls with features skillfully modeled in fine clay reveal artistic tendencies and, perhaps, if these items are cult objects, association with worship. Later, in the Neolithic period (fifth millennium), pottery-making begins. From this period have come three almost life-sized plaster statues built on reed frames, representing a man, woman, and child. The male head, which alone was recovered intact, is a flat disc of clay about one inch thick, with shells for eyes and brown paint for hair. It is possible that a divine triad is represented.

FIFTH MILLENNIUM MODEL OF A MAN’S HEAD. This plaster figure was found at Jericho. The eyes are of shell and the hair and beard have been painted in with simple brush strokes.

FIFTH MILLENNIUM MODEL OF A MAN’S HEAD. This plaster figure was found at Jericho. The eyes are of shell and the hair and beard have been painted in with simple brush strokes.

In Egypt during the Tasian period (named for Deir Tasi in Middle Egypt) which began between 10,000 and 7,000 B.C., man began to cultivate grains, including wheat, barley and flax. In a large Neolithic village near the southwest edge of the delta at Meremdeh Beni-Salamah, oval huts of unbaked mud bricks and a large central granary were found, indicating the development of co-operative enterprise. Woven plant fibers and ornaments of shell, bone and ivory reflect manufacturing and artistic skill. Similar settlements have been found in the Fayum, an ancient oasis west of the Nile.

Near the Caspian Sea and in the upper reaches of the Tigris River, Paleolithic, Mesolithic and pre-pottery Neolithic materials have been recovered, largely from caves. At Mesolithic sites below Lake Urmia (Karim Shahir, Zawi Chemi, Shanidar), circular dwelling foundations of stone with hearths, storage bins, grinding stones and other implements, together with bones of sheep, cattle and dogs, indicate the beginnings of settled culture. These sites may have been occupied only seasonally. At Jarmo in eastern Iraq, a Neolithic site marked the transition to year-round living at one location. No pottery vessels were found. Crude representations of animals and female figures in unbaked clay point to artistic interests perhaps associated with the worship of the mother goddess or the use of fetishes to aid in childbirth and, possibly, to domestication of animals.

Similar patterns of developing society have been observed elsewhere. At Tell Hassuna, south of Mosul, adobe dwellings built around open central courts with fine painted pottery replace earlier levels with crude pottery. Hand axes, sickles, grinding stones, bins, baking ovens and numerous bones of domesticated animals reflect settled agricultural life. Female figurines have been related to worship, and jar burials within which food was placed, to belief in afterlife. The relationship of Hassuna pottery to that of Jericho suggests that village culture was becoming widespread.

The Chalcolithic Age (chalcos, copper; lithos, stone) extended from the middle of the fifth to near the end of the fourth millennium B.C.

During this period the art of smelting and molding copper was developed, and stone and bone tools were now augmented by a limited supply of implements made of this new substance. The skill developed by smiths in the handling of copper is amply illustrated in the several hundred beautifully fashioned cultic items from the end of the Chalcolithic period that were discovered in a cave near the Dead Sea in the spring of 1961.4 Villages and towns of varying size were now spread throughout Palestine and permanent houses were built of stone, mud-brick and wood, although cave living was still common, and near Beer-sheba there was a whole village with underground living and storage quarters. A rich variety of stone, pottery and copper artifacts, fine flint work, paintings and carvings mark cultural growth in this period. New burial patterns were developed. Often the dead were interred in large storage jars, and at other times bodies were cremated and the remains placed in specially made pottery urns and interred in caves.

In Mesopotamia, at Tell Halaf on the Khabour River, a tributary of the Euphrates, hard, thin pottery with a beautiful finish produced by high firing at controlled heats was found. This pottery from the middle of the fifth millennium is decorated with geometric designs in red and black on- a buff slip, but animal and human figures also appear. One figure appears to represent a chariot, thus indicating the use of the wheel. Houses were constructed out of mud brick, but reed structures plastered with mud were also built. Cones of clay, painted red or black or left plain, were often inserted in the mud walls to form mosaics and to protect the wall from weathering.

A small shrine of mud brick from Eridu belongs to the same period. Only foundations and a plastered floor remain, but it is surmised that the upper structure was plastered and painted. Later in the period the shrine was covered over with earth, and a second temple was built above it, placing the new building considerably above the surrounding plateau.

A more pretentious structure from the beginning of the fourth millennium was found at Tepe Gawra, near modern Mosul. Three large buildings of sun-baked brick were located on an acropolis and designed to frame three sides of an open court. Inner rooms were painted in red-purple, and exterior walls were red on one building, white on another and brown on the third. A fourth millennium temple was built at Uruk upon a staged, elevated mound, 140 by 150 feet at the base and 30 feet high. This man-made, mountain-top home for the gods was of pounded clay and layers of sun-dried brick and asphalt. Surmounted by a white-washed temple (65 x 150 x 14 feet) and approached by a steep stairway and a ramp, this structure is known as a ziggurat (from the Assyrian-Babylonian ziqquratu, meaning "to be raised up," hence "a high place") and is the prototype of loftier and more magnificent ziggurats of later periods.

For the first time the cylinder seal is found. Each of these small stone cylinders had distinctive patterns inscribed on its surface, and when rolled over soft, moist clay left a raised design, which could be used as a sign of ownership. About the middle of the fourth millennium, pictographic writing was developed and incised upon clay tablets. As the use of writing increased pictographs became more and more stylized, finally being reduced to wedge-shaped symbols or what is called cuneiform writing. Cuneiform characters were impressed upon a tablet of moist clay with a stylus, and if the document required a signature, a cylinder seal was used. The tablet was baked or allowed to dry, forming a permanent record.

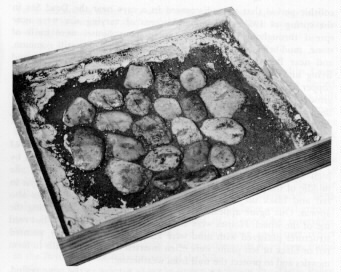

A HEARTH OR INCENSE BURNER found in one of the caves near Beer-sheba. The burner was set in the center of the mud floor and consisted of an arrangement of large pebbles in the form of what has been called "a magic square." Each stone bears a mark in indelible red color, and it is possible that the hearth was used in divination by a priest-magician in the Chalcolithic age. The excavators lifted out the entire section of the floor that contained the hearth and mounted it in a special frame for study and display.

A HEARTH OR INCENSE BURNER found in one of the caves near Beer-sheba. The burner was set in the center of the mud floor and consisted of an arrangement of large pebbles in the form of what has been called "a magic square." Each stone bears a mark in indelible red color, and it is possible that the hearth was used in divination by a priest-magician in the Chalcolithic age. The excavators lifted out the entire section of the floor that contained the hearth and mounted it in a special frame for study and display.

The precise identity of these Mesopotamian people is not known for sure, but on the basis of the sexegesimal arithmetical system utilized on some of the clay tablets, a system also used by the Sumerians, and from references to gods worshiped by the Sumerians, it is presumed that they were Sumerians. Where they came from and when is unknown,5 but they are neither Semites nor Indo-Europeans, and they refer to themselves as "the black-headed-people."

In Egypt the Chalcolithic period is represented by Badarian culture, first found at al Badari. Unusual, ripple patterned pottery was produced in a variety of finishes. Green malachite ore, so important for the beautification of the eyes, was ground on slate palettes that were often ornamented. Skeletal remains indicate that the Badarians were a stocky people and that they believed in some form of afterlife, for the dead were buried in a flexed or sleeping posture with food and equipment.

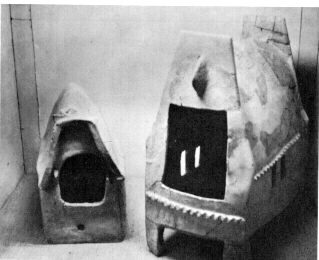

BURIAL URNS FROM THE PLAIN OF SHARON. The deceased person was cremated and the ashes and bones were placed in these clay house-shaped ossuaries. Each urn is individualistic in design and structure, which may indicate stylistic variations in the architecture of the dwellings of the period. The significance of the "nose-like" projection is not known.

The succeeding culture, beginning with the fourth millennium, was called Amratian, after el-Amreh near Abydos, and was centered in Upper Egypt. A new people, tall and slender, appear. Some features of their artifacts demonstrate borrowing from the Badarians, but the extensive use of copper, magnificent flint work, and artistic expressions in slate, ivory and clay mark unique developments. Amratian dead were buried in oval pits in tightly flexed positions. In addition to the usual grave furnishings, ivory and clay figurines of women and slaves were included, leading to the hypothesis that these were miniature substitutions for an older practice of sacrificing living individuals to serve an important individual in the afterlife.

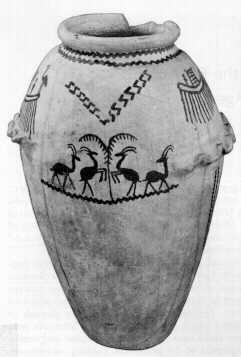

A CLAY VESSEL ABOUT 11 3/4 INCHES HIGH FROM THE LATE GERZIAN PERIOD. The figures are in deep red against a cream colored background. The wavy handles on each side are known as "ledge handles" and are characteristic of vessels of the same period found in Palestine.

A CLAY VESSEL ABOUT 11 3/4 INCHES HIGH FROM THE LATE GERZIAN PERIOD. The figures are in deep red against a cream colored background. The wavy handles on each side are known as "ledge handles" and are characteristic of vessels of the same period found in Palestine.

The Gerzean period began in the middle of the fourth millennium, and for the first time written documents appear in Egypt. Local towns or districts (later called "nomes" by the Greeks) were formed, each with a local symbol that was often mounted on ships to designate district of origin. By conquest, units were joined into larger districts. Gerzian tombs were elaborate: the poor were buried in oblong graves with a ]edge at one side to hold funerary offerings, the rich in tombs lined with mud brick. Gold is found for the first time along with silver and meteoritic iron.

Within the next half millennium significant administrative changes occurred. Gerzean districts of Upper Egypt united under a single ruler who wore a tall white helmet as a crown. Delta nomes united tinder a king who wore a crown of red wicker-work. By 2900 B.C. the two areas had become one, and the single ruler wore both red and white crowns and was known as "King of Upper and Lower Egypt."

Endnotes

- For details cf. Kathleen Kenyon, Archaeology in the Holy Land (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1960) ; E. Anati, Palestine Before the Hebrews (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1963).

- For evidence of much earlier use of fire in other parts of the world, cf. Grahame Clark, "The Hunters and Gatherers of the Stone Age," The Dawn of Civilization, Stuart Piggott (ed.) (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1961), p. 36.

- Called in Hebrew massebah (plural: masseboth). Such pillars are usually associated with Canaanite worship (Exod. 23:24; 34:13; Deut. 7:5; 12:3; II Kings 10:26 f.), or with apostasy in the Hebrew cult (I Kings 14:23; II Kings 17: 10; Hos. 10: 1-2) and are expressly forbidden in the Torah (Lev. 26: 1; Deut. 16:22).

- Cf. P. Bar-Adon, "Expedition C-The Cave of Treasures," The Expedition to the Judean Desert, 1961 (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1962), pp. 215 ff.

- S. N. Kramer, "Sumer," The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible believes that the Sumerians probably came from the Caucasus mountains in the last quarter of fourth millennium. E. A. Speiser, "The Sumerian Problem Reviewed," Hebrew Union College Annual, XXIII (1950-1) 339 ff.

Old Testament Life and Literature is copyright © 1968, 1997 by Gerald A. Larue. All rights reserved.

The electronic version is copyright © 1997 by Internet Infidels with the written permission of Gerald A. Larue.