In this essay I’m going to defend what has come to be known as Hitchens’ razor: “What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence.”[1] The point Christopher Hitchens was making is that miracle claims without any evidence should be dismissed without a further thought. Bayes’ theorem (which I’ll explain shortly) requires the existence of some credible evidence—or data—before it can be correctly used in evaluating miracle claims. So to be Bayes-worthy, a miracle claim must first survive Hitchens’ razor, which dismisses all miracle claims asserted without any evidence. If this first step doesn’t take place, Bayes is being used inappropriately and must be opposed as irrelevant, unnecessary, and even counterproductive in our honest quest for truth.[2]

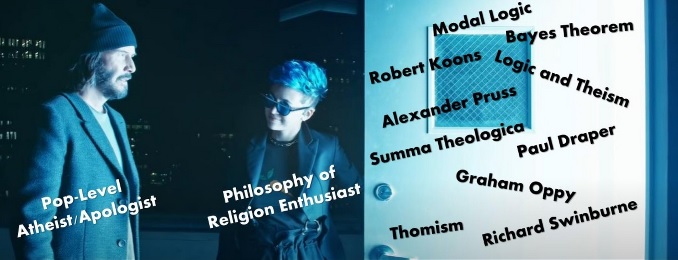

From the outset I should say something about the so-called New Atheism of writers like Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins, and Christopher Hitchens, considered to be pop atheists by the philosophical elite, and not to be taken seriously when speaking of philosophical, biblical, and theological issues. The judgment of both believing and atheist intellectuals is summed up by Steven Poole, writing for The Guardian in 2019: “New Atheism’s arguments were never very sophisticated or historically informed.”[3]I hope to change that perception with regard to Hitchens’ razor. More importantly, I hope to chip away at the value elitist philosophers place on their sophistications.

I do this as a philosopher myself, one who is by no means an anti-intellectual. My difference lies in our motivations. I’m with Karl Marx, who famously said, “The philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.” While other motivations are valuable, such as discussing issues to further our understanding or more completely learn why people disagree, the goal to sharpen our critical thinking skills by eliminating the use of poor arguments is not one of them. For if that’s the goal, any subject matter will do. That’s like playing chess for the sake of learning to play better, which is fun and challenging, but it doesn’t change the world. Why not sharpen our critical thinking skills on the most difficult task of all, changing the world by changing minds? I’m convinced we already know enough to philosophize with a hammer, as Friedrich Nietzche argued.

I’m not alone in this. Julian Baggini echoes my thoughts in his Secular Web review of Michael Martin and Ricki Monnier’s anthology The Impossibility of God.[4] He said of it, “I just don’t believe that detailed and sophisticated arguments make any significant difference to the beliefs of the religious or atheists.” Why? Because “the unintellectual will obviously have no interest in over four hundred pages of carefully argued philosophy. Employing the arguments it contains against someone who has never seriously considered the basic problem of evil is like using a surgeon’s knife to chop down a tree.” But what of intellectuals? Baggini added: “I suspect that a statistically insignificant number of intellectuals will switch sides on the basis of the kinds of arguments contained here.” While we both admit Martin and Monnier’s anthology is valuable because bad philosophy must be answered, Baggini makes a fundamental point—that it probably benefits theists more. For all that their anthology does “is provide fresh challenges to faith, which can only ultimately show its strength. That which does not kill faith usually makes it stronger, and as a matter of empirical fact these arguments aren’t just not lethal, they barely injure.” Baggini concludes that “when we get to this level of detail and sophistication, the war has become phoney. Converts are won at the more general level.”

So much for sophistication if the goal is to change minds.

Theodore Drange says similar kinds of things when reviewing Jordon Howard Sobel’s book Logic and Theism.[5] Its sophistication is plain to see: “The book is long, abstruse, technical (making ample use of symbolic logic and Bayesian notation), and written in a rather difficult style.” While we both recommend it highly for the philosophical elite, Drange questions its value for others, noting, “The main emphasis of the book is on logic rather than theism.” For as an analytical philosopher, Sobel’s “focus is not so much on issues of fact and content as on issues of definition and logical structure.” But for people “who are more interested in theism than logic,” “who have an interest in converting others either to or away from theism,” who “seek arguments that are both cogent and persuasive,” Sobel’s book “has very limited use for such people.” Drange concludes: “Overall, the book is excellent and of great value for professional analytical metaphysicians and philosophers of religion…. But for the average person with an interest in arguments for and against God’s existence, it would be quite safe to pass it by.”

If the point is to change the world, I would rather have more popular books written by people like Harris, Dawkins, and Hitchens than philosophical elites like Martin and Sobel. It’s not that I agree with how Harris and company present their arguments, since they suffer from a lack of precision, depth, and sophistication. It’s rather that I agree with many of their main points, even defending the main point of Dawkins’ ultimate Boeing 747 gambit.[6] I’m happy those points have been thrust into the general population for discussion, especially when they argue against blind faith in bizarre unevidenced miraculous beliefs. On that score, Hitchens’ razor is all anyone needs to honestly evaluate and subsequently dismiss the miraculous claims of religion.

My specialties are theology, philosophical theology, and especially, apologetics. I am an expert on these subjects even though it’s very hard to have a good grasp of them all. Now it’s one thing for theologically unsophisticated intellectuals like Harris, Dawkins, and Hitchens to argue against religion. It’s quite another thing for a theologically sophisticated intellectual like myself to defend them by saying they are within their epistemic rights to denounce religion from their perspectives. And I do. I can admit they lack the sophistication to understand and respond point for point to sophisticated theology. But it doesn’t matter because all sophisticated theology is based on faith, blind faith, unevidenced faith in the Bible—or Koran or Bhagavad Gita—as the word of God, and/or faith in the Nicene Creed (or other creeds), and/or faith in a church, synagogue, or temple. No amount of sophistication changes this fact.

Three Important Razors

(1) Ockham’s Razor

William of Ockham (1285-1349) had previously articulated what is known as Ockham’s razor, whereby “entities should not be multiplied without necessity.” In other words, simpler explanations that explain all the available evidence should be preferred over more complex ones. Ockham cut out a path for modern scientific inquiry because the addition of supernatural entities adds unnecessary complexity to our explanations. Applying Ockham, supernatural explanations of all the available evidence are not preferred because natural explanations are simpler. The best explanations are those that make the fewest assumptions that fit the available evidence.

One can see this in the work of Pierre-Simon de Laplace (1749-1827), a French mathematician, astronomer, and physicist, who wrote a five-volume work titled Celestial Mechanics (1799-1825). In it he offered a complete mechanical interpretation of the solar system without reference to a god. Upon hearing of Laplace’s work, legend has it that Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte said to him, “They tell me you have written this large book on the system of the universe, and have never even mentioned its creator.” To which Laplace reputedly responded, “Sir, I had no need of that hypothesis.”

(2) Sagan’s Razor

Carl Sagan popularized the aphorism, “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence” (ECREE), which is sometimes referred to as Sagan’s razor. It’s based on a reasonable understanding about claims having to do with the nature, workings, and origins of the natural world. These types of claims require sufficient corroborating objective evidence commensurate with the nature of the claim being made. In my anthology The Case against Miracles, I defended this aphorism in chapter 3. I described three types of claims about the objective world and the evidence needed to accept them.

- Ordinary claims require only a small amount of fair evidence.

These are claims about events that take place regularly every day and, as such, require only the testimonial evidence of someone who is trustworthy under normal circumstances. If a trustworthy person tells us there was a car accident on Main Street, we would accept it. There’s no reason not to.

- Extraordinary claims require extraordinary levels of evidence.

These are claims about extremely unusual events within the natural world. They require sufficient corroborating objective evidence. The objective evidence should be sufficient, regardless of whether it’s a large amount of unremarkable objective evidence, or a small amount of remarkable objective evidence. If someone claimed to have consecutively sank 18 hole-in-one’s in a row on a par-3 golf course, we would simply scoff at him. Testimonial evidence alone is always insufficient for establishing an extraordinary claim like that. Such a feat is possible, though. Art Wall, Jr. (1923-2001) holds the record of 45 lifetime hole-in-one’s on the PGA tour. But they were not sunk in consecutive order.[7]

Take for another instance the extraordinary claim that aliens abducted a man. Without any objective evidence, there isn’t any reason to believe his testimony. Objective evidence of his alien abduction would include things like him being beamed back down the very next day into a large crowd of family and friends as an older man, in full view of the alien spaceship, who now shows a superior technological knowledge beyond our comprehension, having in his hand a mysterious rock not from our planet, who was implanted with a futuristic tracking device, and is now able to predict the future with pinpoint accuracy. That’s objective evidence. No reasonable person would reject his story. But we never have this kind of strong objective evidence, and strong evidence is required.

- Miraculous claims are the highest type of extraordinary claims and require the highest quality and/or quantity of objective evidence.

A miracle is an event impossible to occur by natural processes alone. Miraculous events by definition involve divine supernatural interference in the natural order of the world. Other descriptive words are appropriate here, like the suspending, or transgressing, or breaching, or contravening, or violating of natural law; otherwise, they’re not considered miracles, just extremely rare extraordinary events within the world of nature. If you recover after being told you have a one-in-a-million chance of being healed, that’s not equivalent to a miracle, one that suspends natural law. It simply means you beat the odds, and it happens every day, every hour, and every minute, around the globe. The reason believers see evidence of miracles in extremely rare coincidental events is simply because they’re ignorant about statistics and the probabilities built on them. There can be no reasonable doubt about this.

Statistician David Hand convincingly shows that “extraordinarily rare events are anything but. In fact, they’re commonplace. Not only that, we should all expect to experience a miracle roughly once every month.” He is not a believer in supernatural miracles, though: “No mystical or supernatural explanation is necessary to understand why someone is lucky enough to win the lottery twice, or is destined to be hit by lightning three times and still survive.”[8] Extremely rare events are not miracles. We should expect extremely rare events in our lives many times over. No gods made these events happen.

To believe someone’s testimony that a god suspended natural laws to perform a miracle requires enough objective evidence to overcome our extremely well-founded conviction that the world behaves according to natural processes that can be understood and predicted by scientists. David Hume put it this way: “No testimony is sufficient to establish a miracle, unless the testimony be of such a kind, that its falsehood would be more miraculous, than the fact, which it endeavors to establish.”[9] However, human testimony of a miracle is woefully inadequate for this task, as Hume went on to argue. For if we wouldn’t believe someone’s testimony to have sunk 18 hole-in-one’s in a row on a par-3 golf course, we would all rightly dismiss and ridicule as delusional the additional testimony that the golfer flew in the air like Superman from tee to tee in scoring that perfect 18.

Both Ockham’s razor and Sagan’s razor are epistemological in nature, and both are important. Ockham’s razor has to do with the burden of proof. It’s placed squarely on anyone making miraculous claims since they require the existence of additional entities. I think all reasonable people should agree with Ockham’s razor, which explains why scientists should not invoke a god to explain the complexity of the universe, the evolution of life, or the beginnings of life. Sagan’s razor has to do with the kind and quality of evidence needed to establish one’s burden of proof. The more extraordinary the claim, the better the evidence must be. I think all reasonable people should agree with Sagan’s razor, which requires a sufficient amount of credible evidence commensurate with the type of claim being made.

(3) Hitchens’ Razor

Hitchens’ razor has to do with something more fundamental, the need for objective evidence. Lacking it, miracle claims can be dismissed out of hand without a second’s thought. The application of Hitchens’ razor, which comes from a “pop atheist,” stands in opposition to the application of Bayes’ theorem, the domain of sophisticated philosophers.

To be clear, when we dismiss miracle claims, we still have a responsibility to share the reasons why we dismiss them, depending on the number of believers in a society who hold them and how much these beliefs cause harm. We should do what judges do in a court case. They explain why the case is being dismissed so people can understand. Most of the time they simply say the evidence is not there. Judges almost never state the conditions under which they could be convinced, nor specify the amount of evidence needed. They only need to say that the case doesn’t meet the evidential standards required. So all we have to show is why the needed objective evidence doesn’t exist, and that should be the end of it. There wouldn’t be a reason to respond in much depth at all. Depending on the circumstances, ridicule and mockery are even appropriate.[10] Having said this, I will dispassionately suggest what should be convincing, starting with the Christian belief in a virgin-birthed incarnate god.

There is No Objective Evidence for the Virgin Birth So It Should Be Dismissed

All of the miracle claims in the Bible can legitimately be dismissed out of hand since there is no objective evidence for any of them. Consider the Christian belief in their virgin-birthed deity. Just ask for the objective evidence. You don’t need to do anything until that evidence is presented. Until then, such a belief should be dismissed out of hand.

There is an oft-repeated argument that marijuana is the gateway drug leading to dangerous drugs.[11] There is another gateway, one that leads to doubting the whole Bible. I focus on the virgin birth miracle because it’s the gateway to doubting the Gospel narratives, just as Genesis 1-11 is the gateway to doubting the Old Testament narratives. It was for me, anyway. The objective textual evidence from the Bible shows that, contrary to the virgin birth narratives: (1) The genealogies are inaccurate and irrelevant; (2) Jesus was not born in Bethlehem; (3) there was no worldwide census as claimed; (4) there was no slaughter of the innocents; (5) there was no Star of Bethlehem; (6) the virgin-birthed prophecies are faked; and (7) the belief that Jesus was born of a virgin most likely derived from pagan parallels in those days.[12] It was concocted in hindsight to explain how their belief in an incarnate god came into the world to redeem sinners.

The fact is there is no objective evidence to corroborate the Virgin Mary’s story. We hear nothing about her wearing a misogynistic chastity belt to prove her virginity. No one checked for an intact hymen before she gave birth, either. After Jesus was born, Maury Povich wasn’t there with a DNA test to verify Joseph was not the baby daddy. We don’t even have first-hand testimonial evidence for it since the story is related to us by others, not by Mary or Joseph. At best, all we have is second-hand testimony reported in just two later anonymous gospels by one person, Mary, or two if we include Joseph, who was incredulously convinced Mary was a virgin because of a dream—yes, a dream (see Matthew 1:19-24). We never get to independently cross-examine them or the people who knew them, which we would need to do since they may have a very good reason for lying (pregnancy out of wedlock, anyone?).

Now one might simply trust the anonymous Gospel writers who wrote down this miraculous tale, but why? How is it possible they could find out that a virgin named Mary gave birth to a deity? Think about how they would go about researching that. No reasonable investigation could take Mary’s and/or Joseph’s word for it. With regard to Joseph’s dream, Thomas Hobbes tells us, “For a man to say God hath spoken to him in a Dream, is no more than to say he dreamed that God spake to him; which is not of force to win belief from any man” (Leviathan, chap. 32.6). So the testimonial evidence is down to one person, Mary, which is still second-hand testimony at best. Why should we believe that testimony?

On this fact, Christian believers are faced with a serious dilemma. If this is the kind of research that went into writing the Gospels—taking Mary’s word and Joseph’s dream as evidence—we shouldn’t believe anything else the Gospel writers wrote without corroborating objective evidence. The lack of evidence for Mary’s story speaks directly to the credibility of the Gospel narratives as a whole. Since there’s no good reason to believe the virgin birth myth, there’s no good reason to believe the resurrection myth, either, since the claim of Jesus’ resurrection is told in those same Gospels. If the one is to be dismissed, so should the other.[13]

There are other tales in those same Gospels that should cause us to doubt, like tales of resurrected saints who allegedly came out of their tombs and walked around Jerusalem, but who were never interviewed and never heard from again (Matthew 27:52-53). Keep in mind we’re talking about miracle claims from an ancient superstitious era, as Richard Carrier described:

The age of Jesus was not an age of critical reflection and remarkable religious acumen. It was an era filled with con artists, gullible believers, martyrs without a cause, and reputed miracles of every variety. In light of this picture, the tales of the Gospels do not seem very remarkable. Even if they were false in every detail, there is no evidence that they would have been disbelieved or rejected as absurd by many people, who at the time had little in the way of education or critical thinking skills. They had no newspapers, telephones, photographs, or public documents to consult to check a story. If they were not a witness, all they had was a man’s word. And even if they were a witness, the tales tell us that even then their skills of critical reflection were lacking.[14]

In another place, Carrier is unmistakable:

When we pore over all the [early Christian] documents that survive, we find no evidence that any Christian convert did any fact-checking before converting or even would have done so. We can rarely even establish that they could have, had they wanted to. There were people in antiquity who could and would, but curiously we have no evidence that any of those people converted. Instead, every Christian who actually tells us what convinced him explicitly says he didn’t check any facts but merely believed upon hearing the story and reading the scriptures and just “feeling” it was right. Every third-person account of conversions we have tells the same story. Likewise, every early discussion we have from Christians regarding their methodology for testing claims either omits, rejects, or even denigrates rational, empirical methods and promotes instead faith-based methods of finding secrets hidden in scripture and relying on spiritual inspirations and revelations…. Skepticism and doubt were belittled; faith without evidence was praised and rewarded.

Hence, when we look closely, we discover that all the actual evidence that Jesus rose from the dead consisted of unconfirmable hearsay, just like every other incredible claim made by ancient religions of the day. Christian apologists make six-figure careers out of denying this, but their elaborate attempts always collapse on inspection. There just wasn’t any evidence Jesus really rose from the dead other than the word of a few fanatics and a church community demonstrably full of regular hallucinators and fabricators.[15]

What’s Wrong With Bayes’ Theorem?

In his writings and talks, Carrier does a good job of explaining Bayes’ theorem and is its best advocate for examining the claims of history, including those of miracles. It’s a mathematical formula that asks us to input numbers representing determinants of the probability of a given hypothesis we wish to test, say of whether a murder took place.[16] It asks us to input values for the initial likelihood of a murder based on relevant background factors that would increase or decrease that initial likelihood, such as if the suspect had a motive for murdering the victim, or if the victim was suicidal, accident prone, or had a known enemy sworn to kill him. It also asks us to input values for important factors like what we should expect to find if a murder took place compared to if it didn’t. For instance, we might expect to find a dead body that shows evidence of a struggle, as opposed to a dead body lying peacefully in bed. Then it asks us to input values for the probabilities of alternative scenarios, such as the possibility the victim died of an accident, or faked his own death in order to frame the suspect for murder. After inputting the numbers in the equation, we do the calculations, and the resulting percentage is the probability that a murder took place.

I don’t object to using Bayes’ theorem when it’s applied appropriately to questions for which we have prior objective data to determine their initial likelihood, along with subsequent data to help us in our final probability calculations. It’s an excellent tool when these conditions obtain. Nothing I say in what follows undercuts its proper use. But a problem occurs when someone uses Bayes as if it is the only tool in the tool chest. To people who only have a hammer, everything looks like a nail. The proper tool to use on miracles before there is any objective evidence is Hitchens’ razor. Only after there is some objective evidence can we turn to Bayes’ theorem.

My contention is that using Bayes without any prior or subsequent objective data is using it in a pseudostatistical way. Just consider how you could use Bayes to evaluate my bare assertion, without any objective evidence, that I’m levitating right now. That’s all you need to consider and you can understand my point. All miracle claims must begin and end with objective evidence. Without it, there is nothing else to say or do but dismiss them. No math is needed. No other issue demands to be asked or answered.

I have five specific objections to using Bayes’ theorem to assess miracle claims.

- With miracles, there is no objective data to work from.

As just explained, Bayes’ theorem is a mathematical formula that can only be useful when there is objective data to work from. We’re told every logically possible claim has a nonzero probability to it, and that’s true. But the prior probability of a miracle cannot be calculated because we have no prior probability value to input. A pig that can fly of its own power would be a miracle. So we need prior objective data to work from if we’re to use Bayes to assess a specific claim that a pig flew. How many pigs have ever flown of their own power? If anything, the only previous objective data available suggests that the answer is none. So Bayes isn’t the proper tool to use when assessing miracles that lack previous data.

I agree with William L. Vanderburgh, who defended Hume against his critics, that applying Bayes to miracle claims is inappropriate, ineffective, and unnecessary.[17] Hume knew of Bayes’ theorem, but chose not to use it when arguing against miracles.[18] That’s because his objections to miracles also serve to debunk a god of miracles.[19] Even if there is a deity of some kind, which is supposed to tip the balance of probabilities toward accepting miracle claims, Hume argues it’s unreasonable to accept miracle claims as reported by others. As Paul Russell explains, “The key issue, for Hume’s critique of miracles, is whether or not we ever have reason to believe on the basis of testimony that a law of nature has been violated. Hume’s arguments lead to the conclusion that we never have reason to believe miracle reports as passed on to us.”[20] Since there is no good reason to believe testimonies of miracles, there is no good reason to believe in a god of miracles, either. Russell again: “What really matters for assessing Hume’s critique of miracles is to keep in mind that his primary aim is to discredit the actual historical miracle claims that are supposed to provide authority and credibility for the major established religions—most obviously, Christianity.” And on that score Hume’s arguments succeed, since all we have in the Bible are ancient reports of miracles found in ancient texts. So as miracles go by the wayside, so also goes a god of miracles. Just as Hume’s previous objections to design in the universe served to debunk an intelligent, perfectly good divine designer[21], so too his objections to miracles show us there isn’t a good reason to believe in a god of miracles.[22]

When it comes to the supposed miracle of the virgin birth, much less of a virgin-birthed deity, there is no verifiable data that it ever occurred. Since there’s no reason to think any deity was born of a virgin, the odds of such a miracle is at least as low as the number of babies who have ever been born, 1 out of 120 billion! Since we can’t see into the future for the first occurrence of a virgin-birthed deity, there could be an additional 120 billion people or more before such a miraculous event takes place (if ever). So if we justifiably cannot input any numbers for the initial likelihood of this miracle, or only input a prior probability so low that it’s only negligibly distinguishable from zero, we have nothing to input into Bayes’ theorem for us to calculate.

It’s claimed we can use something called “Bayesian reasoning” on miracle claims rather than exact numbers, as with a range of numbers (i.e., not 0.4 but rather 0.4 to 0.01). But if this is true, then we would no longer be using the theorem. For by definition, the application of a theorem requires exact mathematical inputs that can be multiplied and divided. More to the point, the mathematical part of the theorem is the indispensable part of Bayes’ theorem. It’s the part considered to be the original contribution of Thomas Bayes (1702-1761). What makes it important is that the reasoning process behind it “has been quantified, i.e., made it into an expressible equation” for the first time. The “actual process of weighing evidence and changing beliefs is not a new practice.”[23]

In other words, we’ve been reasoning about objective evidence and changing our minds based on the available evidence throughout human history. We’ve also been weighing alternative hypotheses and seeking the best explanation of the evidence for as long as we’ve been reasoning well. So what ends up being called Bayesian reasoning is a cluster of separate questions reasonable people seek answers for when seeking the best conclusion from the available evidence. There’s nothing about Bayesian reasoning we didn’t already do before Bayes quantified it. Every question Bayes asks was already being asked and answered before Thomas Bayes quantified that process. So there’s nothing about what is being called “Bayesian reasoning” that’s specifically due to Bayes’ theorem. One can ask and answer these questions and call it Bayesian reasoning if they want to do so. But it’s not something that originated with Bayes’ theorem, nor is it doing any math, nor is this reasoning helpful unless there is first some objective evidence.

- Using Bayes’ theorem gives undue credibility to some miracle claims over others when none of them have any objective evidence for them.

When working with numbers, all possibilities have a nonzero probability. What number should we assign to miracles, which by definition involve the suspension, transgressing, breaching, contravening, or violating of natural law? It’s argued that we should be generous with our initial probabilities for the sake of argument by inputting higher numbers than warranted when dealing with miracles. But why? Why do that if we’re seeking truth?

Some will say Bayes is useful for evaluating hypothetical scenarios—for example, if one wants to make a case that even given the best imaginable evidence, such evidence still wouldn’t support an opponent’s conclusion that a miracle occurred. But why abandon real concrete cases in favor of imagined hypotheticals? To play this language game is to pretend something false, that there is some evidence for a miracle when there isn’t. How does that serve to advance the honest quest for truth? Even if we do this, Baggini’s earlier quote is still spot on, that “a statistically insignificant number of intellectuals will switch sides” on the basis of such sophistication. So there’s little reason to think this strategy will work. Besides, what makes anyone think we can show that a specific miracle claim has no objective evidence for it, if we grant that it has some objective evidence for it? That’s counterproductive. Keep in mind Baggini also said, “That which does not kill faith usually makes it stronger.”

In my book Unapologetic, I explain why responding to fundamentalist arguments in kind gives their beliefs a certain undeserved respectability. To treat the resurrection story as if it has some objective evidence for it when it doesn’t, is to give it undeserved credibility over the other miracle tales told around the world, in previous centuries, reputedly performed by different gods and goddesses, who have had millions of devotees. It also gives it undeserved credibility for the miracle tales told in the very Gospel texts where we read of the Resurrection. Why is no one doing a mathematical analysis of the Christian virgin-birthed son of God, or the supposed resurrected saints at the time of the death of Jesus (Matthew 27:52-53)? That’s the point!

My critiques of religion focus on the lack of objective evidence for the claims of religion.[24] Imagine if every nonbeliever responded to theistic arguments as I advocate? What if every time an apologist for their sect-specific god offered an argument or quoted their scriptures nonbelievers all responded in unison, saying there is no objective evidence for what they claim? If nonbelievers all responded as Hitchens’ razor calls for, Christian apologists would be forced to consider they are pretending their faith true, just as surely as the Sophists in the days of Socrates were pretending to be wise. This is how we currently treat conspiracy theories from QAnon and others. We should treat religions likewise since they are themselves conspiracy theories made up based on no evidence but anonymous sources.

The only response to an assertion that a pig can fly of its own power is to demand to see one fly under test conditions.[25] Lacking any objective data that shows pigs can fly of their own power, the proper way to deal with such a claim is to dismiss it. To go through the motions of calculating such a probability, beginning with a completely made-up nonzero prior probability, is foolishness. It would grant pig-flying believers the credibility they so desperately crave for such a bizarre claim, just because we took it seriously.

- Using Bayes’ theorem won’t help convince anyone.

Using Bayes is probably worse as a strategy to convince others, for the only people who would sludge through it are far less likely to be convinced by it, and those who use it don’t show any signs of agreeing. Even among people using Bayes’ theorem, they’re coming to very different conclusions:

- Vincent Torley calculated there’s about a 60-65% chance that Jesus rose up from the dead. After reading Michael Alter’s book, Resurrection: A Critical Inquiry (Xlibris Press, 2015). Torley doesn’t think historical evidence can show that a miracle like the Resurrection took place.[26] Now, with his changed mind, the historical evidence for the resurrection of Jesus is probably down to 25-30% for him.

- Richard Swinburne calculated the probability of the bodily resurrection of Jesus at 97%.[27]

- Timothy and Lydia McGrew calculated the likelihood ratio of the resurrection of Jesus to be 1044 to 1, or 1 followed by 44 zeros to 1.[28]

- In Richard Carrier’s estimation, Bayes’ theorem leads him to think the probability that Jesus did not exist could be as high as 67%.[29] So much the worse for a resurrection of a nonexistent person!

Tools are supposed to help. If Bayes helps us, then why does it produce these wildly diverse results? The reason is clear. There are different results precisely because there is no data or evidence for miracles for Bayesians to calculate. This should be evidence all on its own that Bayes is not the right tool when it comes to miracle claims. The right tool is Hitchens’ razor, which requires some credible evidence of a miracle before we give it serious consideration.

- Using Bayes’ theorem won’t help clarify our differences.

We don’t need Bayes to know where our differences are to be found. We already know. The main difference between us is that believers value faith—blind faith, the only kind of faith there is, faith without objective evidence—while nonbelievers value sufficient objective evidence, and seek to proportion their views to the strength of the evidence as best as possible. That’s why we’re nonbelievers.

Christian apologists David Marshall and Timothy McGrew scoff at my depiction of faith as “an irrational leap over the evidence.” They define faith as “trusting, holding to, and acting on what one has good reason to believe is true, in the face of difficulties.” They go on to document that “for nearly two millennia many of the greatest names in the Christian tradition have grounded faith in reason and evidence.”[30] However, it’s quite clear to me that most believers in the churches and colleges tout the virtues of faith without evidence. Just watch the many interventions that street epistemologist Anthony Magnabosco has published on his YouTube channel. There you’ll see the overwhelming anecdotal evidence. When questioned, believers on the street almost always revert to blind faith as an answer.[31]

It seems as though average Christian believers understand their faith better than Christian apologists do, just as those same apologists understood their faith before attending Christian seminaries. Average believers have read and understood their Bible, such as the Gospel story of doubting Thomas, who refused to believe without any objective evidence.[32] The whole point of the tale is that faith without objective evidence is a virtue, not a vice. The lesson to be learned comes from the character of Jesus himself: “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.” This is what 2 Corinthians 5:7 affirms, that “we walk by faith, not by sight,” as does Hebrews 11:1: “Faith is being sure of what we hope for. It is being sure of what we do not see” (NRSV).

In any case, how Marshall and McGrew define faith is irrelevant since there’s no objective evidence for their miracles. Not until they can produce the requisite evidence can they justifiably define faith as trust. Otherwise, their definitions of faith are pure, unadulterated obfuscations hiding the fact that they don’t have any objective evidence for their sect-specific Christian faith. They end up with a faith that trusts in nonexistent objective evidence, so there is every reason not to trust in their faith.[33]

- Imagining what might convince us of a miracle is largely an exercise in futility.

Bayes’ theorem asks us to imagine what might convince us of a given hypothesis. This is a reasonable request in criminal trials, and in other kinds of scenarios where actual evidence is being considered. In order to imagine what would convince us to believe that a miracle occurred, however, we will always have to imagine sufficient objective evidence, and it doesn’t exist. Given the miracle tales told in the Bible, this would require changing the past, and that can’t be done. If an overwhelming number of Jews in first-century Palestine had become Christians, that would’ve helped. They believed in their God. They believed their God did miracles. They knew their Old Testament prophecies. They hoped for a Messiah/King based on these prophecies.[34] We’re even told they were beloved by their God! Yet the overwhelming majority of those first-century Jews did not believe Jesus was raised from the dead.[35] They were there and they didn’t believe. So why should we?

If I could go back in time to watch Jesus coming out of a tomb, that would work. But I can’t travel back in time. If someone recently found some convincing objective evidence dating to the days of Jesus, that would work. But I can’t imagine what kind of evidence that could be. As I’ve argued, testimonial evidence wouldn’t work, so an authenticated handwritten letter from the mother of Jesus would be insufficient. If a cell phone was discovered and dated to the time of Jesus containing videos of him doing miracles, that would work. But this is just as unlikely as his resurrection. If Jesus, God, or Mary were to appear to me, that would work. But that has never happened, even in my believing days, and there’s nothing I can do to make it happen either. Several atheists have suggested other scenarios that would work, but none of them panned out.[36]

Believers will cry foul, complaining that the kind of objective evidence needed to believe cannot be found, as if we concocted this need precisely to deny miracles. But this is simply what reasonable people need. If that’s the case, then that’s the case. Bite the bullet. Once honest inquirers admit the objective evidence doesn’t exist, they should stop complaining and be honest about its absence. It’s that simple. Since reasonable people need this evidence, God is to be blamed for not providing it. Why would a God create us as reasonable people and then not provide what reasonable people need? Thinking people should always think about these matters in accordance to the probabilities based on the strength of the objective evidence.

Believers will object that I haven’t stated any criteria for identifying what qualifies as extraordinary evidence for an extraordinary claim. But I know what does not count. Second-, third-, or fourth-hand hearsay testimony doesn’t count. Nor does circumstantial evidence. Nor still does anecdotal evidence as reported in documents that are centuries later than the supposed events, which were copied by scribes and theologians who had no qualms about including forgeries. I also know that subjective feelings, experiences, or inner voices don’t count as extraordinary evidence. Neither do claims that one’s writings are inspired, divinely communicated through dreams, or were seen in visions.

Chasing the definitional demand for specific criteria sidetracks us away from that which matters. Concrete suggestions matter. If nothing else, a God who desired our belief could have waited until our present technological age to perform miracles, because people in this scientific age of ours need to see the evidence. If a God can send the savior Jesus in the first century, whose death supposedly atoned for our sins and atoned for all the sins of the people in the past, prior to his day, then that same God could have waited to send Jesus to die in the year 2022. Doing so would bring salvation to every person born before this year, too, which just adds twenty centuries of people to save.

In today’s world it would be easy to provide objective evidence of the Gospel miracles. Magicians and mentalists would watch Jesus to see if he could fool them, like what Penn & Teller do on their show. There would be thousands of cell phones that could document his birth, life, death, and resurrection. The raising of Lazarus out of his tomb would go viral. We could set up a watch party as Jesus was being put into his grave to document everything all weekend, especially his resurrection. We could ask the resurrected Jesus to tell us things that only the real Jesus could have known or said before he died. Photos could be compared. DNA tests could be conducted on the resurrected body of Jesus, which could prove his resurrection, if we first snatched the foreskin of the baby Jesus long before his death. Plus, everyone in the world could watch as his body ascended back into Heaven above, from where it was believed he came down to earth.

Christian believers say their God wouldn’t make his existence that obvious. But if their God had wanted to save more people, as we read he did (2 Peter 3:9), then it’s obvious he should’ve waited until our modern era to do so. For the evidence could be massive. If nothing else, their God had all of this evidence available to him, but chose not to use any of it, even though with the addition of each unit of evidence, more people would be saved.

It’s equally obvious that if a perfectly good, omnipotent God wanted to be hidden, for some hidden reason, we should see some evidence of this. But outside the apologetical need to explain away the lack of objective evidence for faith, we don’t find it. For there are a number of events taking place daily in which such a God could alleviate horrendous suffering without being detected. God could’ve stopped the underwater earthquake that caused the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami before it happened, thus saving a quarter of a million lives. Then, with a perpetual miracle, that God could’ve kept it from ever happening in the future. If God did this, none of us would ever know that he did. Yet he didn’t do it. Since there are millions of clear instances like this one, where a theistic God didn’t alleviate horrendous suffering even though he could do so without being detected, we can reasonably conclude that a God who hides himself doesn’t exist. If nothing else, a God who doesn’t do anything about the most horrendous cases of suffering doesn’t do anything about the lesser cases of suffering either, or involve himself in our lives.

This is how to properly think of miracle claims. We simply have to ask for objective evidence. If it doesn’t exist, then say so, say why if you wish to, and be done with it. Just dismiss those claims like reasonable people do to a great number of miracle claims from the beginning of time. Period!

In any case, imagining some nonexistent evidence that could convince us Mary gave birth to a divine son sired by a male god in the ancient superstitious world is a futile exercise, since we already know there’s no objective evidence for it. One might as well imagine what would convince us that Marshall Applewhite, of the Heaven’s Gate suicide cult, was telling the truth in 1997 that an extraterrestrial spacecraft following the comet Hale-Bopp was going to beam their souls up to it, if they would commit suicide with him. One might even go further to imagine what would convince us that he and his followers are flying around the universe today! Such an exercise would be utter tomfoolery, because faith is tomfoolery.

As anthropology professor James T. Houk said, “Virtually anything and everything, no matter how absurd, inane, or ridiculous, has been believed or claimed to be true at one time or another by somebody, somewhere in the name of faith.”[37] Faith-based beliefs cannot be calculated because there’s nothing to base our calculations on.[38]

Final Thoughts

Only if someone thinks there is some credible evidence on behalf of miracles can Bayes be utilized to assess miracle claims. From all I know, there isn’t any.

Again, believers should bite the bullet. We don’t concoct the rules of evidence. If there were a reasonable God, he should know to produce credible evidence for miracles that is commensurate with the rules of evidence he allegedly created.

Again, uncorroborated testimonies cannot establish an extraordinary claim, much less an extraordinary miracle claim of the highest order. Testimonies alone are not objective evidence, nor are hearsay, circumstantial evidence, anecdotal stories, subjective experiences, or claims of divine dreams, visions, or inspiration.

If nonbelievers wish to go into greater depth in dismissing an unevidenced miracle claim, even though it’s not strictly necessary, they can still use the full range of reasoning and scientific skills available by culling from the best of the best. It depends on the level of sophistication needed. Such sophistication does trickle down to the university level, and to less sophisticated educated people in the pulpit, and in the pews. Just keep in mind that the greater the sophistication, the less convincing the argument becomes, since from my experience Baggini is correct that conversion takes place on the general level.

Notes

[1] Christopher Hitchens, God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything (New York, NY: Atlantic Books, 2008), p. 150.

[2] This is a significantly edited essay derived from chapter 1 (pp. 17-49) of my anthology, God and Horrendous Suffering (Denver, CO: GCRR Press, 2021). The original chapter title is “In Defense of Hitchens’s Razor” and contains nearly 15,000 words.

[3] Steven Poole, “The Four Horsemen Review – Whatever Happened to ‘New Atheism’? The Guardian (January 31, 2019). <https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/jan/31/four-horsemen-review-what-happened-to-new-atheism-dawkins-hitchens>.

[4] Julian Baggini, “Review of The Impossibility of God” (2005). The Secular Web. <https://infidels.org/library/modern/julian-baggini-review-martin/>.

[5] Theodore M. Drange, “Jordan Howard Sobel’s Logic and Theism” (2006). The Secular Web. <https://infidels.org/library/modern/theodore-drange-sobel/>.

[6] See “Case Studies in Atheistic Philosophy of Religion,” chapter 4 of my book Unapologetic: Why Philosophy of Religion Must End (Pitchstone Publishing, 2016). An excerpt of the chapter is available online.

[7] “Golfer Art Wall Jr.: Masters Champ, Hole-in-One Artist” (October 2021). Golf Compendium. <https://www.golfcompendium.com/2021/10/art-wall-jr-golfer.html>. Most PGA golf courses only have four par-3’s for every 18 holes. Par-5 holes, at an average of 560 yards, are longer than professionals can drive the ball, although even then, there have been a handful of hole-in one’s. See E. Michael Johnson, “Did You Know: There Have Been Five Holes-in-One on Par 5s (Yes, Par 5s!)” (April 14, 2020). Golf Digest. <https://www.golfdigest.com/story/did-you-know-there-have-been-five-holes-in-one-on-par-5s-yes-par-5s>.

[8] David J. Hand, The Improbability Principle: Why Coincidences, Miracles, and Rare Events Happen Every Day (New York, NY: Scientific American/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014). See also: Leonard Mlodinow, The Drunkard’s Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 2009); Joseph Mazur, Fluke: The Math and Myth of Coincidence (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2016); and Jeffrey S. Rosenthal, Knock on Wood: Luck, Chance, and the Meaning of Everything (Toronto, Canada: HarperCollins Publishers, 2018).

[9] David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, chapter 10, part 1, 13.

[10] One misunderstanding of ridicule is that it changes the minds of the people we ridicule. It doesn’t. They double down. But they aren’t likely to change their minds anyway. It can and does change the minds of people who are undecided. Another misconception is that I’m arguing we should ridicule believers to their faces. See John W. Loftus, “On Justifying the Use of Ridicule and Mockery” (January 17, 2013). Debunking Christianity blog. <https://www.debunking-christianity.com/2013/01/on-justifying-use-of-ridicule-and.html>. See also John W. Loftus, Unapologetic: Why Philosophy of Religion Must End (Durham, NC: Pitchstone Press, 2016), pp. 211-235.

[11] I think this is largely false, but don’t get sidetracked by it.

[12] On these points, see the links in Loftus, “The Gateway to Doubting the Gospel Narratives is the Virgin Birth Myth” (June 16, 2020). Debunking Christianity blog. <https://www.debunking-christianity.com/2020/06/the-gateway-to-doubting-gospel.html>.

[13] On the resurrection, see Loftus, The Case against Miracles (United Kingdom: Hypatia Press, 2019), chapter 17.

[14] Richard Carrier, “Kooks and Quacks of the Roman Empire: A Look into the World of the Gospels” (1997). The Secular Web. <https://infidels.org/library/modern/richard_carrier/kooks.html>.

[15] Loftus, The End of Christianity (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2011), pp. 62-63; emphasis mine. I’ll leave it to Carrier to explain why Bayes’ theorem is needed to assess the resurrection miracle even though he admits it has no evidence for it. I thank him for highly recommending my book, God and Horrendous Suffering, where my objections to Bayes are stated in chapter 1, despite his disagreement with me (so far).

[16] The details are explained in Satoshi Nakamoto, “Bayesian Reasoning – Explained Like You’re Five” (July 23, 2015). LessWrong blog. <https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/x7kL42bnATuaL4hrD/bayesianreasoning- explained-like-you-re-five>.

[17] On this, see William L. Vanderburgh, David Hume on Miracles, Evidence, and Probability (Lanham, MD, Lexington Books, 2019), which I reviewed in the Appendix to The Case against Miracles, pp. 551-560. Vanderburgh’s book is a direct response to the criticisms of John Earman, Hume’s Abject Failure: The Argument against Miracles (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2000).

[18] Vanderburgh, David Hume on Miracles, p. 121.

[19] See Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, chapter 10.

[20] Paul Russell & Anders Kraal, “Hume on Religion” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2017 edn.) ed. E. N. Zalta (Stanford, CA: Stanford University, 2017), §6 (“Miracles“). <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2017/entries/hume-religion/>.

[21] This is the deity Hume excoriates in his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion.

[22] See Loftus, The Case Against Miracles, pp. 79-109.

[23] See note 10.

[24] See Loftus, “The Five Most Powerful Reasons Not to Believe (December 16, 2020). Debunking Christianity blog. <https://www.debunking-christianity.com/2020/12/the-five-most-powerful-reasons-not-to.html>.

[25] Craig S. Keener has touted a lot of anecdotal miracle stories in his 2-volume work, Miracles: The Credibility of the New Testament Accounts (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2011). To understand how to scientifically examine miracle claims, see Darren M. Slade, “Properly Investigating Miracle Claims” in The Case against Miracles (pp. 114-147) ed. John W. Loftus (United Kingdom: Hypatia Press, 2019). See especially: Theodore Schick, Jr., and Lewis Vaughn, How to Think about Weird Things: Critical Thinking for a New Age, now in its 8th edition (Boston< MA: McGraw-Hill, 2019); Carl Sagan, The Demon Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark (New York, NY: Random House, 1996); the Amazing James Randi, An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural (New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 1995); Joe Nickell, The Science of Miracles: Investigating the Incredible (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2013); and Michael Shermer, Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time (New York, NY: Holt Paperbacks, 2002).

[26] Loftus, “Christian Apologist Vincent J. Torley Now Argues Michael Alter’s Bombshell Book Demolishes Christian Apologists’ Case for the Resurrection” (September 26, 2018). Debunking Christianity blog. <https://www.debunking-christianity.com/2018/09/christian-apologist-vincent-j-torley.html>.

[27] Richard Swinburne, The Resurrection of God Incarnate (Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 2003).

[28] Timothy and Lydia McGrew, “The Argument from Miracles: A Cumulative Case for the Resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth” in The Blackwell Companion to Natural Theology (pp. 593-662) ed. William Lane Craig and J. P. Moreland (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012).

[29] Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Phoenix Press Ltd, 2014).

[30] Tom Gilson and Carson Weitnauer, True Reason: Confronting the Irrationality of the New Atheism (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 2013), p. 149.

[31] See Anthony Magnabosco’s YouTube channel.

[32] In John 20:24-29. On this, see “Doubting Thomas Tells Us All We Need to Know About Christianity” (April 19, 2021). Debunking Christianity blog. <https://www.debunking-christianity.com/2021/04/doubting-thomas-tells-us-all-we-need-to.html>

[33] The lack of any objective evidence for miracles is why there are five major strategies for doing apologetics. Upwards to eighty percent of Christian theologians/apologists reject the primary need for objective evidence for their faith in favor of other things. On this, see my chapter 6, “The Abject Failure of Christian Apologetics” (pp. 171-209) in The Case against Miracles.

[34] To see how early Christian’s misused Old Testament prophecy, see Robert J. Miller’s excellent book, Helping Jesus Fulfill Prophecy (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2015).

[35] The most plausible estimate of the first-century Jewish population comes from a census of the Roman Empire during the reign of Claudius (48 CE) that counted nearly 7 million Jews. See the entry “Population” in Encyclopedia Judaica, vol. 13. In Palestine there may have been as many as 2.5 million Jews. See Magen Broshi, “Estimating the Population of Ancient Jerusalem.” Biblical Archaeological Review Vol. 4, No. 2 (June 1978): 10-15. Despite these numbers, Catholic New Testament scholar David C. Sim shows that “Throughout the first century the total number of Jews in the Christian movement probably never exceeded 1,000.” See “How Many Jews Became Christians in the First Century: The Failure of the Christian Mission to the Jews. Hervormde Teologiese Studies Vol. 61, No. 1/2 (2005): 417-440.

[36] Loftus, “What Would Convince Atheists To Become Christians? The Definitive Answers!” (April 4, 2017). Debunking Christianity blog. <https://www.debunking-christianity.com/2017/04/what-would-convince-atheists-to-become.html>.

[37] James T. Houk, The Illusion of Certainty (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2017), p. 16.

[38] Thanks goes to Keith Augustine who offered criticisms that ended up making this paper better.