The First Coming: How the Kingdom of God Became Christianity (1986–electronic edition 2000)

Thomas Sheehan

III

How Jesus Became God

The first mention of Jesus anywhere in literature was made twenty years after he died, and is found in a text that records the already developed status of his reputation. Writing around 50 C.E., Saint Paul began a letter to a group of his converts in Greece with the following greeting:

To the Church of the Thessalonians

in God the Father and

the Lord Jesus Christ:

Grace to you and peace. (I Thessalonians 1:1)

This greeting–the very first sentence of Christian Scripture ever to be written–shows that within two decades of Jesus’ death the Christian community had already elevated the prophet beyond his own understanding of his status and had endowed him with two titles, “Lord” and “Christ,” neither of which he had dared to give to himself.

Paul also asserts that Jesus is soon to return from the heavens in order to bring God’s kingdom to earth. To be sure, it is likely that Jesus,

178

before he died, had come to believe he was the long-awaited eschatological prophet; and it is possible that Paul expected God the Father to vindicate Jesus’ message in the very near future by sending a separate apocalyptic figure–the Son of Man of the Book of Daniel–to usher in the fullness of the kingdom of God that Jesus was preaching. But in this letter to the Thessalonians the apocalyptic scenario of the Book of Daniel is reworked so as to make Jesus himself be the Son of Man, soon to appear in glory. The Son of Man, that formerly mysterious apocalyptic figure whom pious Jews earnestly awaited, now had a recognizable human face: He was Jesus of Nazareth.

You turned to God from idols, to serve a living and true God and to wait for his Son from heaven, whom he raised from the dead, Jesus, who delivers us from the wrath to come. (I Thessalonians 1:9-10)

For the Lord himself will descend from heaven with a cry of command, with the archangel’s call, and with the sound of God’s trumpet. And the dead in Christ will rise first; then we who are alive, who are left, shall be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air; and so we shall always be with the Lord. (4:16-17)

Paul, of course, was not alone in his belief. By the middle of the century there were several thousand converts scattered around the Mediterranean who, thinking that they were living at the brink of history, had readied themselves for the Last Day. And that day was imminent.

As for the times and seasons, brethren, you have no need to have anything written to you. For you yourselves know well that the day of the Lord will come like a thief in the night. When people say, “There is peace and security,” then sudden destruction will come upon them as labor pains come upon a pregnant woman, and there will be no escape. (5:1-3)

Clearly, by mid-century when Paul wrote his first epistle, Christianity was well on its way to establishing Jesus’ reputation as we have

179

known it for almost two millennia. If by 50 C.E. the prophet was already acknowledged as Lord and Christ, before the end of the century he would be thought of as the equal of God himself.

The odyssey of Jesus of Nazareth from crucified prophet to divine ruler of the cosmos is an extraordinary event in Western intellectual history and, given the current state of biblical scholarship, one of the best documented. The process consisted in a gradually increasing identification of Jesus himself with the kingdom of God that he had preached; and one of the major results of this process was a dramatic change in the sense of time and history that Jesus’ proclamation had introduced into Judaism.

The heart of Jesus’ message had been the presence of the future: the arrival of God among men and women. Jesus heralded the end of religion and religion’s God insofar as he proclaimed the present-future as the fulfillment of what religion had always claimed to be about. In that sense Jesus did announce the “end of history”: the end of alienation from God and oneself, from one’s fellow men and women and the entire created world. Paradoxically, however, Jesus’ message of the present-future became the basis of its own undoing. After the prophet’s death his disciples identified God’s presence with Jesus himself and relegated that presence to an apocalyptic future when Jesus would return to usher in the kingdom once and for all.

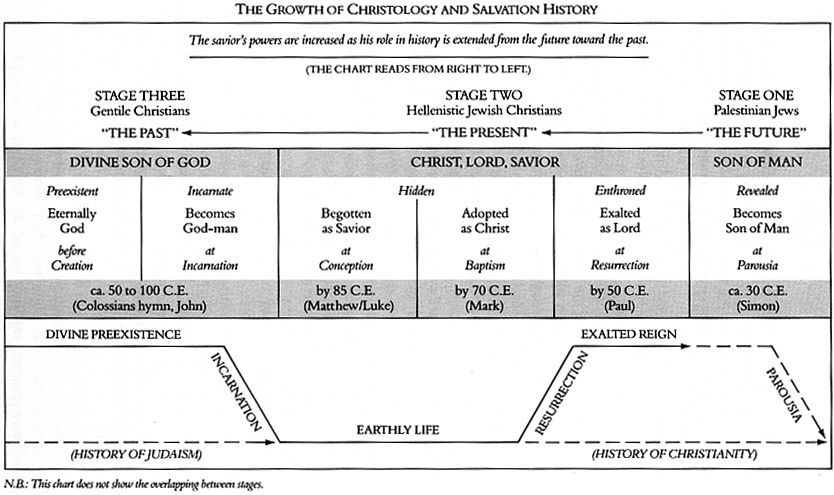

This third part of the book is about that twofold process: the growth of Jesus’ reputation and the corresponding undoing of his message.[1] Our objective is to examine the evolution of the Christian faith over its first fifty years, from its earliest formulations to its full-blown interpretation of Jesus as the Son of God. I will trace this evolution via the church’s transformation of Jesus’ notion of history. We will examine how Jesus’ ideal of the present-future disintegrated as his own reputation grew in the decades after his death. Although this evolutionary process was quite complicated, we can distinguish three general phases within a broad spectrum of christological variations:

STAGE ONE: THE APOCALYPTIC FUTURE. Whereas Jesus had dissolved the future of Jewish apocalyptic expectations into the presence of that future (the dawning kingdom), Christianity reconstituted the apocalyptic future by recasting Jesus as the future Son of Man.

180

STAGE TWO: THE HEAVENLY PRESENT. Christianity then drew that apocalyptic future back into the present moment by reinterpreting Jesus as the Lord and Christ who was already reigning in heaven.

STAGE THREE: THE CHRISTOLOGICAL PAST. Finally the church projected the Lord Jesus into the past history of the cosmos by declaring that he had preexisted from before creation as the savior of the entire world.

These three stages in the evolution of early Christianity are associated with three more or less distinct groups of early converts to belief in Jesus, two of them made up of Jews and the third of Gentiles.

The first members of the Jesus-movement were Aramaic-speaking Jews who lived in Palestine. Some, like Simon Peter and the first disciples, had heard Jesus preach the kingdom of God when he was alive; others came to faith through the preaching of the original disciples in the first years after Jesus had died. It was this community that first projected Jesus’ reputation into the future by declaring that he would be the coming Son of Man.

Alongside these Aramaic-speaking believers there grew up in Palestine a second and distinct group of converts to the Jesus-movement: the Hellenistic Jews of the Mediterranean Diaspora, who had absorbed Greek language and culture. At the time of Jesus some of these Hellenistic Jews, or their ancestors, had returned to Palestine from the Diaspora, and they continued to speak Greek rather than Aramaic, to read the Scriptures in the Septuagint (Greek) translation, and probably to worship in their own Greek-speaking synagogues throughout Palestine. Within a few years of joining the Jesus-movement, they (apparently unlike the Aramaic-speaking believers) were persecuted by the local religious authorities, probably for vigorously proselytizing on behalf of their new and unorthodox beliefs. As a result of this persecution, many Hellenistic Jews left Palestine for Samaria and the Diaspora, most notably Antioch in Syria, where they first acquired the name “Christian.” It was these Hellenistic Jewish believers in Palestine and the Diaspora who, within a few years of the crucifixion, effected a momentous shift in the interpretation of Jesus. If the Aramaic-speaking believers had projected Jesus into an apocalyptic future–the end of

181

time, when Jesus would begin to reign–the Hellenistic Jewish Christians pulled the moment of Jesus’ glorification back into a heavenly present by declaring him to be already reigning as the Lord and Christ, who was now enthroned at God’s right hand until his second coming in glory.

The third group of early believers was composed of Gentile converts. The Jesus-movement was originally a Jewish affair, and until the middle of the century, Gentile converts to the movement were expected to join Judaism, that is, to undergo circumcision and observe the Jewish law. It was most likely the Hellenistic Jewish believers who began evangelizing pagans, and these Gentile converts were originally associated with the liberal synagogues of Greek-speaking Jews in the Diaspora.

Around mid-century, however, the more conservative Jerusalem community apparently agreed that Gentile converts to the Jesus-movement did not have to be circumcised so long as they obeyed certain basic Jewish laws, mostly dietary in nature. This decision, which is usually attributed to the “Council of Jerusalem” (ca. 48 or 49 C.E.), made possible a new and freer mission to the Gentiles and the formation of distinct communities of Gentile converts to Christianity.[2] It was these new communities, rooted as they were in both Judaism and the Graeco-Roman world, that projected Jesus’ reputation into the mythical past by declaring that he had preexisted as a divine being before becoming a man.

All three groups maintained a basic unity and continuity in their faith, although they articulated their beliefs in different ways. These differences in expression help to reveal the evolution of Jesus’ status after his death. Even though there is a great deal of overlapping, we may characterize three more or less distinct interpretations of Jesus, each of which points to one of the three groups of believers:

(1) THE APOCALYPTIC JUDGE: The Aramaic Jews held that Jesus had been appointed by his Father to assume the role of Son of Man in the near future.

(2) THE REIGNING LORD AND CHRIST: The Hellenistic Jews declared that Jesus was already reigning as the messiah in the interim before his glorious return.

182

(3) THE DIVINE SON OF GOD: The Gentile converts came to believe that Jesus was God’s divine Son who had preexisted even before creation, had become a human being to save mankind, and had returned to heaven after his death.

183

1. The Apocalyptic Judge

Faith in Jesus began as, and for a long time remained, a movement within Judaism. The first disciples saw themselves not as belonging to a new religion, not even as an exclusive sect within Judaism, but rather as orthodox Jews who were proclaiming what Israel had always awaited but only now had attained: the fullness of Yahweh’s presence.

The disciples began preaching the victory of Jesus in the spring of 30 C.E. in the synagogues of northern Galilee, probably starting in Simon’s home village of Capernaum. We may imagine Simon, like Jesus before him, entering the synagogue on the Sabbath with a small group of believers.[3] Simon’s reputation as a follower of the prophet has already become well known in the area, and he is invited to read from the Scriptures. He chooses a text from the prophet Isaiah:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

__ because the Lord has anointed me

__ to bring good tidings to the poor. …

He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives

__ and recovering of sight to the blind,

184

To free those who are oppressed

__ and to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor. (cf. 61:1-2)

Then, referring the text to Jesus, Simon proclaims:

This scripture was fulfilled before your very eyes

__ in Jesus of Nazareth,

__ a man attested to you by mighty works

__ that God did through him in your midst.

For Moses said:

__ “The Lord shall raise up for you

__ a prophet from among your brethren, as he raised me up.

__ You shall listen to him in whatever he tells you.

__ And whoever does not listen to him shall be destroyed.”This Jesus was crucified and killed

__ at the hands of lawless men.

But the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob,

__ the God of our Fathers,

Has glorified his servant Jesus.

__ And of that we are witnesses.

He has loosed the pangs of death,

__ for it was not possible for Jesus to be held by death.

And heaven must receive him

__ until the time of restoration of all things.But you are the heirs of the covenant

__ that God made with our forefathers.

Repent, therefore, and turn again,

__ that your sins may be blotted out.

And the Lord will send the time of comfort.

__ (See Luke 4:21; Acts 3:13-25 and 2:22-24)

Simon proclaimed that time was running short. The eschatological spirit was already being poured out–they had already received him. It was as Yahweh had promised through his prophet Joel:

In those days

__ I will pour out my Spirit

185

And I will display portents in heaven above

__ and signs on earth below.

The sun will be turned into darkness

__ and the moon into blood

Before the great Day of the Lord dawns.

__ (Acts 2:18-20, citing Joel 2:29-32)

And so Simon and the others went down to Jerusalem from Galilee to await that Day of the Lord.[4] There they invoked the God of the end-times: “Abba, may thy kingdom come!” And they called out to Jesus: “Maranatha. Come, master!” (I Corinthians 16:22; Revelation 22:20). They prayed and preached, but above all they waited for the apokatastasis pantôn, the final establishment of all God had promised to Israel (Acts 3:21). They lived as an eschatological community totally given over to their coming Lord and to each other. In what is most likely an idealized portrait of those first days in Jerusalem, Luke writes that

the faithful all lived together and owned everything in common. They sold their goods and possessions and shared out the proceeds among themselves according to what each one needed.

They went as a body to the Temple every day but met in their houses for the breaking of the bread. They shared their food gladly and generously. They praised God and were looked up to by everyone. Day by day the Lord added to their community those destined to be saved. (Acts 2:44-47)

The preaching of the earliest believers took place during the period of the “literary blackout”–the years before the New Testament was written–that covered the first twenty years of the Jesus-movement. We possess no Christian Scriptures earlier than Paul’s First Epistle to the Thessalonians in about 50 C.E., but numerous fragments of oral tradition from that period have survived (often much changed by later circumstances) in the writings of the New Testament, and from those fragments exegetes have been able to reconstruct a plausible version of the original Aramaic-Jewish interpretation of Jesus in the period immediately after he died.

186

That first interpretation was composed of two moments, one of which dealt with Jesus’ earthly life, the other with his eschatological future. That is, the earliest disciples thought Jesus had been God’s eschatological prophet during his life on earth and would soon become the Son of Man at the end of time. Let us consider each moment in turn.[5]

Jesus certainly had thought of himself as a prophet; and even though he did not explicitly designate himself as the eschatological prophet, there was no doubt that he presented his mission in eschatological terms and that his disciples hoped he would soon prove to be that long-promised herald of the end. Many Jews believed that when this final prophet came, he would be “anointed” with God’s Spirit. That is, he would be a “messiah,” although not in a nationalistic or political sense.

In the broadest terms, a messiah (“anointed one”; in Greek translation, christos) was a deputy of God, one who had received the Spirit and was appointed to act in Yahweh’s name. One such anointed figure was the future Davidic king whom many Jews awaited as a national and political savior; but Judaism likewise expected an anointed prophet, whom Moses himself had promised:

Moses said, “The Lord God will raise up for you a prophet from your brethren as he raised me up. You shall listen to him in whatever he tells you.” (Acts 3:22, citing Deuteronomy 18:15, 18)

This “prophet like Moses” would preach conversion, interpret the Law properly, serve as a “light to the Gentiles,” and announce God’s definitive arrival among his people. It was this kind of prophetic (not political) messiah that the Aramaic Jewish believers understood Jesus to have been. In so doing they were simply turning their earlier hope about Jesus into an explicit declaration of faith in him. This first moment of the early Aramaic interpretation of Jesus was in strict continuity with what his disciples had believed him to be before he died.

However, the second moment of the interpretation–Jesus as the future Son of Man–represented a qualitative leap in the disciples’ faith. In one sense, this “leap” was only an adjustment, although a momentous one, in the then-current Jewish expectation. The disciples gave a recognizable human face–that of Jesus–to the heretofore

187

anonymous apocalyptic judge whom Daniel had called the Son of Man. However, the consequences for Jesus’ message were tremendous. Jesus himself had never spoken of returning at the end of time; in fact, at one point in his ministry he may well have expected to be still alive at the end. At most Jesus may have believed–this is much debated–that the definitive arrival of the kingdom would be signaled by the appearance of God’s apocalyptic deputy, the Son of Man. Whenever Jesus mentioned this Son of Man (if indeed he did mention him), he always referred to him as a future figure separate from Jesus himself.

Soon after the crucifixion, however, believers invented and put into Jesus’ mouth statements which implied that at the eschaton Jesus himself would return as the Son of Man. For example, when Mark wrote his account of Jesus’ trial, he constructed it so as to have the high priest ask Jesus whether he was the messiah. And Mark had Jesus respond:

I am; and you will see the Son of Man sitting at the right hand of the Power and coming with the clouds of heaven. (14:62)

But even in inventing such claims, the early believers maintained a distinction between the Jesus of the past, who had preached the kingdom of God, and the Jesus of the future, who would reappear as God’s apocalyptic deputy. They did not think that Jesus, during his life on earth, had been an incarnation of the future Son of Man; nor did they claim that he was now fulfilling that role in heaven, that is, that he had already become the apocalyptic judge. Rather, they believed Jesus would become the Son of Man in the near future, that he had been “ordained by God [to become] the judge of the living and the dead” (Acts 10:42). They believed that when he was raised to heaven, Jesus had been designated or appointed for that role but that he would not begin exercising it until the end arrived.

The first disciples thought that between Jesus’ past mission as eschatological prophet and his future mission as Son of Man there lay a brief interval during which God was gathering his people together in readiness for the end. The brevity of that in-between time was the source of the eschatological urgency both of their message and of their style of life. The brevity of the interval also had a negative consequence for christology: It left the disciples with little or nothing to say about

188

who Jesus was or what he was doing during this supposedly short period. They could say only that “heaven must receive him until the universal restoration comes” (Acts 3:21). Jesus was, so to speak, “on hold” for a short while until God would put him into action again at the end of time.

The disciples understood the interval of time between Jesus’ death and his second coming less as a chronological moment in time with a before-and-after than as the frozen and breath-catching instant between seeing the flash of an explosion and feeling its full impact. The assumed brevity of the interval provided the earliest believers with little incentive for working out christological theories about Jesus. The title “Son of Man” was soon enough replaced by “messiah” (in Greek, christos) as a way of speaking of the role for which Jesus was designated. And since God had appointed Jesus the future judge at the moment when he rescued him from death, the church began to apply the names “Messiah” and “Christ” to Jesus in his suffering and crucifixion. Similarly the title “Son of God” (which was the equivalent of “Messiah” and had no reference to divinity) became another way of identifying Jesus’ future role, just as the title “Son of Devid,” which indicated Jesus’ qualification for messiahhood, came to apply to Jesus during his earthly life. But all such titles were meant only to spell out the two moments that made up the eschatological faith of the first believers: Jesus had been the final prophet, and he was now momentarily in heaven until his return as apocalyptic judge.

During the interval between his resurrection and the parousia, Jesus was operatively present in the disciples’ proclamation of the kingdom. But he was not the object of their preaching so much as its motivation. His words and deeds had been functionally associated with the arrival of the kingdom, and indeed Jesus would function that way again in the future. But the Church did not yet make an ontological identification of Jesus with God’s presence among men. During his life he was perceived as the locus of the kingdom of God, just as after his death he became the focus of the disciples’ preaching. But he was not yet understood to be the content of the kerygma. The early Jewish believers did not think that Jesus was already enthroned and reigning at God’s right hand or that he was currently acting with God’s power. All that was to come only when Jesus returned at the end of time. During the

189

brief interval he was only the messiah-designate. The fulfillment of God’s plan was soon to come, and thus everything about the interval was charged with an overwhelming sense of urgency.

But as this supposedly brief instant dragged on, the status of Jesus during the interval became problematic. Even if his absence from earth could be accounted for by “appearances” from heaven, what was Jesus actually doing in heaven during the lengthening time before his return? It will not do to say that Simon and the early disciples believed that Jesus was alive only in their preaching (“Jesus rose into the kerygma,” as Rudolf Bultmann phrased it) or in the continuation of his ideals in the church (“Jesus’ cause goes on,” as Willi Marxsen puts it). On the contrary, in the eyes of the early church, the kerygma and the continuing cause of the eschatological prophet derived all their meaning from the future return of Jesus. If he was not about to come back, then the entire eschatological business–“resurrection,” “appearances,” kerygma, and even Jesus himself–would be called into question. And in fact it soon was. The months and years passed without the parousia happening; the brief interval began to turn into a long period of waiting. How long would God keep Jesus in heaven before sending him again?

The next stage in the enhancement of Jesus’ status came in large measure as a response to that delay; and that step was taken by the second group of early believers, the Hellenistic Jews. But before moving on to that, let us take stock of the first evaluation of Jesus.

As We have seen, after the crucifixion the disciples came to believe that, by God’s initiative, the kingdom Jesus had preached–the presence of God among men and women–was still dawning and in fact was soon to arrive in its fullness. The proper response of the believer to that eschatological event was to live God’s present-future in hope and love. The disciples were convinced that the Father had ratified the “word” of his prophet–not just what Jesus had said about the kingdom, but first and above all how Jesus had lived. That was what had effected the Father’s presence among his people.

Among the earliest interpretations that accrued to this belief were the formulae “Jesus has appeared [from the eschatological future]” and “Jesus has been raised.” In these early proclamations we can discern a momentous twofold shift away from Jesus’ original message of the kingdom. To begin with, these proclamations presume the identification

190

of the word of Jesus (the efficacious way he lived the present-future) exclusively with Jesus himself; and then further, they announce the identification of Jesus himself with the coming kingdom of God.

This twofold shift lies at the origins of Christianity, and its importance can scarcely be exaggerated. To believe that the way Jesus had lived effected the dawning of the kingdom was to identify an exemplary praxis, imitable by all, for realizing God’s presence among men. That was the “word” of Jesus: not his “words” as pieces of information, but his deed, what he had lived out and embodied. Jesus’ deed had been his all-consuming hope for the Father’s presence, a hope that he lived out among his fellow men. The future had become present, and Jesus lived that present-future by turning hope into charity, eschatology into liberation. He lived that hope-as-charity so intensely that he became it. In that sense, yes, Jesus “was” his word, and his word “was” (that is, effected) the kingdom. But the proper way for his followers to affirm that belief was to live the present-future as Jesus had lived it. Strictly speaking, this is what they believed God had ratified: Jesus’ lived hope, which could remain effective only in the further living of it.

However, the disciples’ original mistake lay in exchanging that lived hope for the man who had lived it. And in turn the disciples projected that man into the apocalyptic future as a pledge that their own hope would soon be fulfilled. They surrendered a lived hope for a dead hero whom their faith brought back to life. The memory of the hero grew–first of all into an apocalyptic future, when he would supposedly bring what in fact he had already brought: God’s presence. Soon enough the weight of that expected future (what Jesus would do at the parousia) would shift back toward the present (what Jesus was now doing in heaven). And finally that weight would be spread over the whole of history, the past as well as the present and future: The church would interpret Jesus as God himself, the preexistent creator as well as the now reigning Lord and the future judge of the world.

This whole process began when the first disciples gave God back his future and identified it with Jesus of Nazareth. As far as Jesus had been concerned, there was no longer a future any more than there was a past. He stood, so he thought, at the moment when God’s future had begun to become present and to abolish the reign of sin. But his disciples

191

exchanged that presence of God’s future for the future of God’s presence. Jesus had freed himself from religion and apocalypse by transforming hope into charity and by recasting future eschatology as present liberation. But his disciples redirected their attention into a fantastic future and thus reinserted Jesus into the religion he had left behind. They remade God’s presence-among-men into God’s presence-yet-to-come and eventually into Jesus himself. Henceforth one’s relation to God (who Jesus had said was already present) was determined by one’s relation to Jesus (who the disciples now said was temporarily absent).

The future-oriented christology of the first disciples did not yet identify the kingdom with the person of Jesus. The earliest disciples did see their master as the unique embodiment of what the kingdom meant, but in so doing they were identifying Jesus with what they took to be his functions of prophet (in the recent past) and judge (in the very near future). The process of a full ontological identification of Jesus with the kingdom, and eventually as the equal of God, would require more time and would climax in the development of a normative christology that interpreted Jesus–not just in his functions but in his very being–as divine.

But at this earliest stage of christology, the disciples were in fact beginning the process of undoing Jesus’ message by reconstituting an apocalyptic future. They started reifying what had begun as a challenge: the challenge of living with one’s neighbor in a way that befit the Father’s irrevocable commitment to be God-with-men. There at the beginning the disciples missed the point, even if ever so slightly. But the consequences were to be enormous. As Aristotle once said, “The smallest initial deviation from the truth is multiplied later a thousand-fold; what was small at the start turns out a giant at the end.”[6]

192

2. The Reigning Lord and Christ

The Jesus-movement was soon to be in trouble. The problem was not that the disciples frequently met resistance from the religious establishment: That, in fact, was grist for their mill. The threat of excommunication from the synagogue, the martyrdom of some believers and the forced emigration of others, even the start of the Zealot uprising in 66 C.E. that would end in the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem four years later–all such problems fit the apocalyptic program. They were the eschatological woes that signaled the imminent end of the world that the disciples so earnestly awaited. Jesus had predicted:

When they persecute you in one town, flee to the next; for truly, I say to you, you will not have gone through all the towns of Israel, before the Son of Man comes. (Matthew 10:23)

The serious problem, rather, was the lengthening of the supposedly brief interval between Jesus’ hidden vindication at his death and his public reappearance in glory. Not only was the parousia being progressively

193

delayed, but within thirty years of Jesus’ death the founders of this eschatological movement within Judaism would begin dying off, with no return of Jesus yet insight. This state of affairs occasioned major adjustments in the way the movement looked at history and how it evaluated Jesus himself. The clue to understanding the progressive enhancement of Jesus’ status from failed prophet to divine savior lies in the early believers’ response to this “problem of the interval.”

The period that we now consider stretches from the first years of the Jesus-movement, through the composition of Saint Paul’s epistles (about 50-55 C.E.) up to the writing of the Synoptic Gospels (about 70-85 C.E.). Our focus is on the Hellenistic Jewish Christians who began spreading the message beyond the geographical confines of Palestine and the religious limits of Judaism. The development of christology during this period is rich and very complex, but some general lines can be discerned: (1) a gradual deemphasizing of eschatology;[7] (2) a heightening of Jesus’ status during the so-called interval;[8] and (3) the “backward migration” of Jesus’ messianic status, first from the parousia to the resurrection, then back to his baptism, and then even further back to his conception.[9] Whereas the Aramaic-speaking Jews hoped Jesus would become the messiah at the end of the world, the Hellenistic Jewish converts came to believe that he had already been constituted the messiah from his mother’s womb. The Jesus-movement, which originally looked forward, now started glancing over its shoulder to what was believed to have occurred in the past and was now a cosmic fact: that Jesus was already the Lord and Christ, the messianic Son of God.

Properly speaking, Christianity begins with these Hellenistic Jewish believers. They were the first to introduce Jesus into the Western world with the Greek title christos, thus earning themselves the name “Christians” (Acts 11:26). More important, the changes they wrought in the movement’s theology elevated Jesus to an intermediate christological plateau, from which he would later be launched to the heights of divinity.

The Aramaic-speaking believers, for all their “liberalism” vis-à-vis the religious establishment, were rather conservative in comparison with Hellenistic Jewish Christians. The Palestianian Jewish members of the Jesus-movement regularly visited the Temple, obeyed the Mosaic

194

195

Law (even if in a different spirit from that of some of the Pharisees), and looked forward to the coming apocalyptic end. On the other hand, the Greek-speaking converts, who breathed the cosmopolitan air of Hellenism, were more liberal when it came to the minutiae of the Law and the Temple cults (even though they were quite strict about the Ten Commandments), and were less interested in eschatology and futuristic messianism than their Aramaic-speaking colleagues. The Hellenistic Jewish Christians also took it upon themselves to widen the circle of evangelization to include Gentiles as well as Jews, and in so doing they liberalized some of the strictures, particularly regarding observance of the Law, that more conservative Jewish believers imposed on converts to the movement. As a consequence, the Hellenistic Jewish Christians soon found themselves in conflict not only with their conservative Aramaic-speaking colleagues but also with the religious establishment in Jerusalem, which began persecuting them in the early thirties (Acts 8:1). Within a very few years after Jesus’ death many of them left Palestine for the Diaspora, taking with them a new ferment of ideas about who Jesus was and what he was currently doing in heaven.

At first, the Hellenistic Jewish Christians merely translated from Aramaic into Greek the christological titles that expressed the early Church’s understanding of Jesus. For example, they rendered the Aramaic masiah (“anointed one”) and mare (“lord”) with, respectively, the Greek words christos and kyrios. But pressured by the continuing delay of the parousia, they then took a momentous step and revised their notions of Jesus’ status during the ever-lengthening interval. They began a process within christology which would continue for the rest of the century until Jesus would be recognized as the equal of God himself.

That process consisted in enhancing Jesus’ status prior to the parousia. (See the accompanying chart.) This enhancement, which was begun by the Hellenistic Jewish Christians and continued by their Gentile converts, moved in the opposite direction from the christology of the first believers. The original impulse of the church had been to augment Jesus’ status in a forward direction, toward the future parousia, when he would be revealed as God’s chosen messianic son. However, the Hellenistic Jewish believers began enhancing Jesus’ status in a backward direction. They disconnected the “christological moment” (the point

196

where, according to faith, Jesus became the chosen one of God) from the parousia and began edging it backward toward earlier moments: first to Jesus’ resurrection, then to his baptism in the Jordan, and finally to the very moment of his conception. The third group of early believers, the Gentile Christians, would later take the climactic step and declare that their savior had preexisted in heaven as God’s divine Son before he became incarnate as Jesus.

This “backward migration” of christology brought about a major change in the church’s vision of history. The Hellenistic Jews took the first step by toning down the eschatological thrust of the original believers and pushing Jesus’ “christological moment” back through his resurrection to the beginning of his earthly life. But by the end of the century the Gentile Christians went further and formulated a cosmic view of history controlled by their vision of Jesus. Their savior had existed in heaven as God’s divine Word–his instrument of creation and revelation–even before the beginning of the world; he had become incarnate as a human being and had suffered and died for the sins of mankind; and at his resurrection he had been exalted to heaven, where he now reigns in glory until the end of the world.

The present section focuses on what the chart designates as Stage Two of christology and salvation history, that is, the period of the backward enhancement of Jesus’ christological status, first from the future parousia to the resurrection; then further back to his baptism in the Jordan; and finally back to the very moment of his conception. Later we shall consider Stage Three of the christological progression: how the Gentile Christians came to interpret Jesus as divine.

THE RESURRECTION: JESUS EXALTED AS LORD

Whereas the Aramaic-speaking believers thought Jesus had only been designated to be the future messiah, the Hellenistic Jewish Christians believed that he had already been enthroned as Christ and Lord from the time he was raised from the dead. Instead of a brief and temporary “assumption” into a heavenly limbo of inactivity with the promise of an imminent return, Jesus was now thought to be already “exalted” (enthroned) and ruling at his Father’s right hand even before the

197

parousia. The church took two psalms which celebrated the royal coronation of a past Davidic king and interpreted them as applying to Jesus, who they now thought was reigning alongside his Father. Note the following excerpts from two sermons, one attributed to Simon Peter, the other to Paul, which use those psalms:

Acts 2:32-35:

This Jesus God raised up, and of that we are all witnesses. Being therefore exalted at the right hand of God, and having received from the Father the promise of the Holy Spirit, he has poured it out, as you see and hear. … For David himself says:

__The Lord [Yahweh] said to my Lord [Jesus]:

_____”Sit at my right hand, till

______I make thy enemies

______a footstool for thy feet.” [Psalm 110:1]Acts 13:32-33:

We bring you the good news that what God promised to our fathers he has fulfilled to us their children, as it is written in the second psalm,

__”Thou art my son,

___this day I have begotten thee.” [Psalm 2:7]

Now thought to be ruling as the Christ and “Son of God” (God’s chosen one, not his ontological son), Jesus becomes the functional equivalent of God himself.[10] That is, without yet sharing the nature of God, Jesus is now seen as carrying out functions previously attributed to his Father. Jesus pours out the eschatological Spirit upon those who are to be saved; in fact, he becomes a “life-giving spirit” (I Corinthians 15:45). He receives power from his Father and is made the Lord of the living and the dead (Romans 1:4, 14:9). Above all, he becomes the Savior through whom God reconciles the world to himself. “Jesus … delivers us from the wrath to come” insofar as he “gave himself for our sins to deliver us from the present evil age” (I Thessalonians 1:10; Galatians 1:54).

The idea of Jesus as the Savior who atoned for the sins of the world (which is a commonplace among Christians today) was far from

198

obvious to the early church. In fact, it took some years before Christians settled on the now normative interpretation of Jesus’ death as an expiatory sacrifice for sin. To begin with, Jesus in fact was not condemned to death by the Sanhedrin for claiming to be the messiah. (That claim was from Mark, not Jesus.) Not only did he refuse to advance that claim, but many men before and after him did claim to be the messiah without having any trouble with the Sanhedrin. The most plausible reason that history can currently give for the condemnation of Jesus was that he was perceived as defying the authority of the religious establishment.

However, in a first effort to give a theological meaning to Jesus’ death, his disciples interpreted the crucified Jesus as a martyred prophet who had been rejected by men but glorified by God.[11] Although this early interpretation is quite simple when compared with later understandings of Jesus’ death, it did bring together into one christological evaluation the heretofore separate themes of (1) the Jewish saint or holy person as God’s suffering servant and (2) the coming Son of Man. In support of this schema of rejection and glorification, the church applied to Jesus the words of the psalmist:

The stone which the builders rejected

__has become the cornerstone.

This is the Lord’s doing;

__it is marvelous in our eyes. (Psalm 118:22f.)

At a second stage of reflection the church enhanced this interpretation by providing the crucifixion with an apocalyptic meaning that changed it from a historical accident into an eschatological inevitability. According to this view, in the days of eschatological woe before the final end, Jesus, like all just and God-fearing Jews, was bound to undergo suffering at the hands of sinners, but with the assurance that God would not forever abandon him to death.

Only at a third stage–perhaps before mid-century–did Hellenistic Jewish Christians begin to think of Jesus’ death as a vicarious atonement for the sins of mankind. For those believers, and especially for Saint Paul, Jesus’ death and resurrection took on a transcendent and cosmic significance. It was God’s universal saving act, his transformation

199

of the very being of the world, the apocalyptic beginning of a “new creation” (II Corinthians 5:17; Galatians 6:16). With Jesus’ death and resurrection God’s will to save all mankind, which was understood to have been his purpose from the beginning of the world, was seen as becoming a cosmic force now operating through the mediation of the exalted and enthroned messiah.

Jesus himself was that force personified, the human (yet somehow suprahuman) Lord and Christ who was no longer merely the prophetic locus of the coming of the kingdom nor the apocalyptic focus of the disciples’ preaching. Jesus as Lord, Christ, and Savior was now the content of the Hellenistic Jewish Gospel. In one sense this Gospel continued the central theme of Jesus’ own message–the fact that God had given himself over to be henceforth present among mankind–but on the other hand it changed Jesus’ preaching in a fundamental way. Henceforth the God-for-man whom Jesus had proclaimed would be understood as God-in-Jesus saving the entire world. In the words of Saint Paul, “God was in Christ reconciling the cosmos to himself’ (II Corinthians 5:19).

This Hellenistic Jewish “enthronement christology,” which took the resurrection as the moment when Jesus became Lord and Savior, marked Christianity’s first important step beyond its original Jewish roots. The earlier “parousia christology” had merely refocused Judaism’s expectations by giving the coming Son of Man a known and recognizable face, that of Jesus of Nazareth. This first Jewish christology did not claim that Jesus was now operating with God’s power; during the interval it awarded him only the proleptic role of messiah-designate. But the Hellenistic Jewish Christians pulled that future role, and the titles that went with it, back into the present. Jesus, now enthroned in heaven, was already functioning with the power he would later exercise in the sight of all at the future parousia. That is, the Hellenistic Jewish Christians made up for the delay in Jesus’ future coming by enhancing his present powers. If the first disciples exchanged an earthly present-future for an apocalyptic future, this second wave of believers began dissolving the apocalyptic future into a heavenly present. The parousia slipped into the penumbra of the Church’s concern, and Christianity slowly changed from a movement focused on the future to a religion centered on a present redeemer.

200

THE BAPTISM: JESUS ADOPTED AS CHRIST

Within twenty years of his death, “Jesus the future Messiah” had become “Jesus the already reigning Christ.” But within two more decades–that is, by the time of Saint Mark’s Gospel–Jesus’ “christological moment,” the point when, according to believers, he entered into his complete glory, would migrate one step further back: to his baptism in the Jordan. A text that expresses this new evaluation of Jesus is found at the beginning of Saint Mark’s Gospel:

In those days Jesus came from Nazareth in Galilee and was baptized by John in the Jordan.

And when Jesus came up out of the water, immediately he saw the heavens opened and the Spirit descending upon him like a dove. And a voice came from heaven,

__”Thou art my beloved Son.

___With thee I am well pleased.” (1:9-11)

This text documents the growing interest of Hellenistic Jewish Christians in Jesus’ earthly life and ministry and not just in the cosmic saving event of his death and resurrection. Their concern was not “historical” in our modern sense but religious: They wanted to know the prophet of Galilee and Judea as their Savior. Therefore, this first mention of the “historical” Jesus dates his adoption by God as the chosen one not to the resurrection but to the beginning of his public life.[12] This viewpoint is echoed in a later text in which Simon Peter reminds his listeners of

the word which was proclaimed throughout all Judea, beginning from Galilee after the baptism which John preached: how God anointed Jesus of Nazareth with the Holy Spirit and with power; how he went about doing good and healing all that were oppressed by the devil, for God was with him. (Acts 10:38)

Neither of these two Scripture texts clarifies what Jesus’ status was before that moment at the Jordan when God chose him to be the messiah. The presumption is that Jesus was simply a pious Jew and that

201

he was “adopted” by God for the office of proclaiming the eschatological kingdom. Once he was adopted and constituted as God’s messianic deputy, his words and works were thenceforth charismatically directed by the Spirit of God. Therefore, even before his resurrection he was the Christ, the messianic “Son of God.”

In Mark’s Gospel, however, God’s adoption of Jesus as the Christ was a hidden affair, known only to Jesus and to the demons whom he exorcized (3:11, 5:7). According to Mark, Jesus never tells his disciples that he is the Christ, and when God miraculously announces the fact to Peter, James, and John during a heavenly vision, Jesus enjoins them to tell no one about the matter (9:9). But during his passion and death the “messianic secret” comes out at two crucial moments. According to Mark, Jesus tells the Sanhedrin that he is the Christ, and for that he is condemned to death (14:61-64). Then, having been rejected by his own religious leaders, Jesus is recognized as messiah by a Gentile, the Roman centurion who was supervising the crucifixion: “Truly this man was the Son of God” (15:39).

The “secret” of Jesus’ election to the office of messiah is a literary device employed by Mark for theological purposes. It allowed him to take the christological moment–which believers had already shifted from the parousia to the resurrection–and move it one step further back to the beginning of Jesus’ prophetic ministry. However, it was not Mark who invented the messianic interpretation of Jesus’ ministry, for the early title of eschatological prophet already embodied the conviction that Jesus’ life had been directed by the power of God. What Mark did, rather, was to stabilize this conviction under the stronger rubric of “messiah” or “Christ.” In this way, Jesus the Mosaic prophet was seen as permanently endowed, from his baptism onward, with the gift of the Spirit that God had reserved for the end of time.

Intentionally or not, Mark leaves the impression that Jesus, before being adopted at his baptism to be God’s messianic son, was an ordinary human being and not the Christ. Other believers apparently found this “adoptionist christology” inadequate to express their conviction that Jesus was already constituted as the Christ from the very beginning of his life. Therefore, the next stage in enhancing Jesus’ status would consist in pushing the christological moment one step further back: to his physical conception.

202

THE CONCEPTION: JESUS BEGOTTEN AS SAVIOR

Mark’s Gospel opens with the preaching of John at the Jordan and has nothing to say about Jesus’ life before he was baptized. But some fifteen years later (ca. 85 C.E.), Matthew and Luke begin their Gospels with narratives about the infancy of Jesus–stories which purported to show that Jesus was the Christ from the first moment of conception in his mother’s womb. These narratives, which make up the first two chapters of both these Gospels and from which Christians have forged the story of Christmas, are not at all historical accounts of Jesus’ earthly beginnings but testimonies of faith that grew out of the burgeoning christology of the Hellenistic Jewish Christians.

Popular ideas notwithstanding, the infancy narratives in the first two chapters of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke say nothing about an “incarnation” of God as man. Quite the contrary, the fetal Jesus whose conception is narrated in these two stories is entirely human, despite his miraculous beginnings. Neither Gospel claims that God the Father sent his preexistent and ontologically divine Son to take on human flesh in the Virgin Mary’s womb. Such an “incarnation christology” would be the product of the next stage in the enhancement of Jesus’ status (for example, in John’s Gospel).[13] At this point, rather, we find a more modest “conception christology,” which maintains simply that the human fetus that would eventually be born as Jesus of Nazareth was conceived with the blessings of God and was the Messiah from the beginning of his human life. These Gospels do not claim that God was Jesus’ physical or ontological Father, or that Jesus was born of a hieros gamos, a sacred marriage between the Virgin Mary and the Holy Spirit. Despite popular interpretations, these Gospels are not concerned with the anatomical aspects of Jesus’ conception. Their point, rather, is that however the conception may have come about (Luke allows for the possibility that Jesus was conceived in the natural way), that conception was the work of God and the child who was born was God’s messiah.

Despite the religious biologism to which they later gave rise, and quite apart from whatever curiosity about Jesus’ biography these accounts may have satisfied en passant, the “conception christologies” of

203

the Gospels of Matthew and Luke were aimed primarily at correcting earlier adoptionist theories by showing that Jesus was the Christ from the first moment he was human.

In a few short years the Hellenistic Jewish churches of the Diaspora managed to create much of what we know as Christianity. The climactic step, the proclamation of Jesus as the divine Son of God, was still to come; but within fifty years of the crucifixion, the groundwork for that was solidly laid. The consequences were momentous.

FROM ESCHATOLOGY TO HISTORY. Hellenic Jewish Christianity revamped the early believers’ eschatological sense of history. For Simon and his brethren–the first generation of believers–the present and the recent past were seen as being entirely ruled by the future parousia. The present existence of these believers was nothing but an expectation of the future, and that future would publicly vindicate all that the prophet Jesus had once been. But with the new emphasis on Jesus’ messiahhood–reaching from the past moment of his conception to the present moment of his heavenly reign–Christianity began surrendering its focus on eschatology. However, Christianity did not thereby regain Jesus’ sense of the present-future but rather began fashioning its notion of history as a progression toward the eschaton.

One response to the delay of the parousia was the writing of the Gospels. To counter the climate of doubt aroused by Jesus’ failure to return, some gospel accounts embellished the Easter experience with elaborate apocalyptic stories that concretized the “resurrection” of Jesus by providing him with a preternatural body that was physically seen, touched, and elevated into heaven. Other New Testament texts portrayed Jesus comforting his disciples by warning them that the parousia might be delayed: “It is not for you to know the times and seasons which the Father has fixed by his own authority” (Acts 1:7); “I am with you always, to the close of the age” (Matthew 28:20). Some believers even declared that the eschaton had already arrived with the first appearance of Jesus and that the kingdom was continuing to grow through the ministry of the Church. (Classical Roman Catholic ecclesiology

204

was built in large measure on this notion of “realized eschatology.”)

As the future continued to recede into the distance, the period of the present gained in importance. We have noted how the Aramaic-speaking believers reclaimed the apocalyptic future that Jesus had already left behind. But when that misplaced eschaton failed to come about, the Hellenists created a present that weighed more heavily on Christianity than the apocalyptic future ever could. By opting for a once hidden and now currently ruling Lord and Christ, the Hellenistic Jewish Christians created a heavenly present and the beginnings of a sacred past that would soon become the vertebrate structure of Christian salvation history. In the process, they began substantializing Jesus’ salvific functions and identifying the kingdom of God with those functions, thus opening the way to a substantialized divinization of the person of Jesus himself. The message of Jesus became less a challenge to live the reign of God-with-mankind and more an invitation to revere this one particular man who had now assumed God’s functions.

From that point on, history was dated and centered. The dawning eschatology preached by Jesus, which had become the anticipated apocalypse proclaimed by Simon, now gave way to the present rule of Christ with, at very best, a parousia postponed until a far-distant future. The Christian church stepped firmly into history, which now seemed to move forward on two parallel lines, one celestial, the other terrestrial. Celestial history was the trajectory of Christ’s reign in heaven, with his saving work basically accomplished and his second coming indefinitely delayed. Terrestrial history was the parallel trajectory of the church’s patient movement toward the ever receding future of the parousia. And even though Christianity’s feet were firmly planted in earthly history, its head was in the clouds.

We know that while we are at home in the body we are away from the Lord. We would rather be away from the body and at home with the Lord. (II Corinthians 5:6, 8)

My desire is to depart and be with Christ. (Philippians 1:23)

FROM FUNCTIONAL TO ONTOLOGICAL CHRISTOLOGY. The change in the church’s sense of history followed from its reevaluation of Jesus. From

205

an early emphasis on his prophetic functions (what he had done in the recent past and would do again in the near future), the church began to stress his nature (who he had been in the past and who he now was in heaven). Strictly speaking, Hellenistic Jewish christology did not take this leap, but it did prepare the way. As the retrospective evaluation of Jesus increased and as the powers he was to exercise at the parousia were extended backward through the “interval” to the beginning of his life, the question of who Jesus was (ontological christology) began to gain importance alongside the question of what he had done (functional christology). Could he have been just a man? Once the “conception christology” of Matthew and Luke had raised the stakes over the “adoptionist christology” of Mark, momentum built up for an even higher wager: that Jesus’ origins stretched back beyond his merely human beginnings, to divine preexistence in heaven.

206

3. The Divine Son of God

During the first century of Christianity, pagan religion in the Mediterranean was characterized by a syncretism of Greek philosophy, Jewish theology, and a variety of mystery cults. This rich mixture defies synthesis, but we can identify within it a widely diffused interest in personal and cosmic salvation. This was an interest to which Christianity responded as it took the third step in enhancing the status of Jesus.

The Graeco-Roman world was in social and religious ferment when Christianity was born. Three centuries earlier, with the conquests of Alexander the Great, the tidy world of the Greek city-state had begun to crumble, and with it went the security of living one’s life within a cohesive whole in which politics, religion, and social intercourse were integrated. In the less stable cosmopolitanism which ensued, Greek culture found itself bound under Roman political authority and confronted with the strange practices of Oriental religions. The old gods seemed to have fled. They had lost their footing in the everyday life of the polis; and disappeared into the transcendent Beyond, which philosophers attempted to divine. Their traces could still be found in the ancient poems of Homer and Hesiod, but the gods’ crude morals

207

and fickle ways, as depicted in those works, hardly seemed models for ethical and political action. The ancient divinities had lost their power to do the one thing they had once been good for: holding the world and the social order together.[14]

At the time when Christianity was entering the Diaspora, there was a general sense among the Mediterranean peoples that the whole cosmos was in the grip of forces and spirits that imposed a hard fate on the course of natural and human events. For ancient peoples, Greeks and Romans included, the world of the stars and planets had never been a neutral or strictly “natural” realm. The sky was the abode of the immortal gods, the realm of eternity, stability, and bliss, in contrast with earthly change and human suffering. In both popular religion and learned philosophy, the sky was thought to be filled with gods and demigods who influenced everything from the course of history to the humors of the body. Even in postexilic Judaism, when Yahweh seemed to retreat into the further reaches of transcendence, angelic intermediaries were multiplied to fill the gap left by Yahweh’s absence and to guarantee both his contact with, and his detachment from, the world. In popular Jewish cosmology, each planet, star, and material substance, as well as every nation on earth, was governed by an angel who guaranteed God’s presence and dominion in the world.

Perhaps never before had the oppressive sense of cosmic fate weighed so heavily on Mediterranean peoples. There was a widespread sense, derived in good measure from Near Eastern cults, that the “lower heavens” (the area of sky beneath the moon) was controlled by obscure cosmic forces that held one’s life and destiny within their power. The Greeks had long had a sense of the tension between order and chaos and knew the difference between nature’s purposeful activity and its raw, unshaped power. But these were distinctions made by reason in an effort to know and control the irrational, or at least to hold it at bay. The new religious forces, on the other hand, lay beyond the power of reason and the orderliness of nature. These forces constituted a system of ironclad fate—heimarmenê–that defied human comprehension and control. All one could do was to achieve harmony with the cosmic system. Even in Stoic philosophy, where the power of fate was seen as hypostasized Reason (Logos), men and women were powerless to do anything but surrender themselves to its inevitability. As Seneca put it, “The fates lead the willing and drag the unwilling.”[15]

208

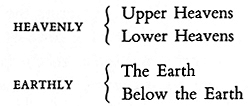

In most of these systems, whether pagan or Jewish, the cosmos was seen as divided between the heavenly and the earthly realms, each of which in turn was divided into two.

The upper ethereal heavens, sometimes called epourania, were where the highest God or gods dwelt; in Jewish and Christian models of the cosmos, this was the dwelling place of Yahweh. The lower heavens were the abode of demons and spirits, both good and bad. In some systems it included the region of the stars and planets, in others it was confined to the “air” (Greek aêr), that is, the atmosphere under the moon. In the epistles of Paul and his colleagues, these cosmic powers were given various names: “principalities,” “authorities,” “powers,” “the world-rulers of the darkness of this age,” “the spirits of evil in the upper heavens,” and in general “the god of this world.” Sometimes they were angels, sometimes the personified “elements of the cosmos,” which had become mythologized into living beings who determined the course of earthly events. These elements were seen as intermediaries of the higher gods, and one had to worship them to gain access to the fullness (plêrôma) of divine power and, ultimately, to immortality.

The third level was the dwelling place of men and women during their earthly subjection to the power and influence of demons and angels. And finally, below the earth, according to some systems of Jewish apocalypse, were subterranean caves where the fallen angels were enchained. Such demonology and mythical cosmology was common in both paganism and apocalyptic Judaism, and was part even of certain Stoic theories of the universe. All these mythologies shared a common notion: The destiny of men and women was out of their control.

The need for salvation from the cosmic forces of the lower heavens was strongly felt and took various forms. One way to achieve liberation was to placate these powers by observing astrological holy days and abstaining from certain foods. Another means was participation in

209

mystery cults that promised initiates the wisdom and knowledge that would save them. The older Greek mystery religions of Demeter, Dionysos, and Orpheus were augmented by still others coming from the East: the cults of Isis and Osiris from Egypt, of Cybele and Attis from Phrygia, of Atargatis and Adonis from Syria, and later, from Persia, the religion of the Aryan deity Mithra. These rites answered a felt need for spiritual rebirth by associating the participants with a god who died or disappeared and then either returned to life or in some way shared divine power with the initiates. At a more sophisticated level, the Stoics taught that one must achieve harmony with, or resign oneself to, the universal principle of Reason, which ruled the cosmos in the form of fate, or providence (pronoia). In all such Systems, whether astrologism, mystery religions, or Stoic philosophy, the desired salvation was both individual (spiritual redemption, ethical conversion) and cosmic (reconciliation with, or resignation to, the forces ruling the world).

Hellenistic Jewish Christians lived in the midst of this religious ferment, influencing it and being influenced in turn. As they gained converts among Gentiles and as these new believers took up the work of evangelization, the Christian proclamation of the person and works of Jesus was gradually adapted to the new religious situation. In the process, Christian evangelists rewrote their vision of Jesus and made him into the cosmic redeemer who had conquered the malevolent powers of the world.[16]

In the previous section we saw how Greek-speaking Jewish Christians promoted Jesus beyond the original roles of eschatological prophet and future Son of Man by moving his future parousial powers back into a present reign. This second-stage Hellenistic christology was continuous with first-stage Aramaic christology on two points. First, it maintained a functional emphasis on Jesus’ saving actions and did not yet hazard an ontological evaluation of his nature. And second, even though Hellenistic christology shifted the historical focus from the future to the present, it still kept the parousia at least in the peripheral vision of Christianity.

However, all of that began to change in the last half of the century. As the church became more populated by Gentiles and as the parousia continued to be delayed, Christians reshaped their faith in two important ways. First, they began to affirm the ontological divinity of Jesus.

210

And second, they scored this belief in the key of an elaborate cosmic drama which comprised three acts: (1) the savior’s preexistence as God in heaven, (2) his incarnation as the God-man Jesus, and (3) after his redemptive death and resurrection, his re-exaltation as Lord and Christ and his recognition as God (see [chart], p. 194).

In constructing this cosmic drama Christianity drew upon a late-Jewish tradition that spoke of the odyssey of God’s “Wisdom” through the cosmos. In the years after the exile, when Yahweh seemed to withdraw from the earth and become more transcendent, Judaism began to hypostatize and personify various features of his divinity–for example, his “Spirit” and his “Word”–which were represented as distinct from him, yet closely related to God. These hypostatizations mediated between Yahweh and mankind, thus preserving both God’s transcendence and his presence to the world.[17]

One of the most important of these hypostatizations was God’s “Wisdom” (Hebrew hokhma; Greek sophia), which was personified as a woman. She was the first of God’s creations, brought into being “at the beginning of his work, the first of his acts of old” (Proverbs 8:22), and she was a perfect image of God himself.

[Wisdom] is a breath of the power of God and a pure emanation from the glory of the Almighty; therefore can nothing defiled enter her.

She is a reflection of eternal light, a spotless mirror of the working of God, and an image of his goodness. (Wisdom 7:25-26)

As a hypostatization of God, Wisdom assumed two of God’s functions toward the world: She was the agent of the rest of his creation, “the fashioner of all things” (Wisdom 7:22); and she was the mediatrix of revelation who reveals “all things that are either secret or manifest” (7:21). As God’s own revelatory word seeking to find a place among mankind, Wisdom periodically entered the world, either directly or through intermediaries, to offer Israel the liberating knowledge of the Law. The Book of Proverbs asks:

Does not wisdom call?

__Does not understanding raise her voice?

On the heights beside the way,

211

__in the paths she takes her stand.

Beside the gates in front of the town,

__at the entrance of the portals she cries out:

“To you, O men, I call,

__and my cry is to the sons of men. …

Hear, for I will speak noble things,

__from my lips will come what is right. …

Take my instruction instead of silver,

__and knowledge rather than choice gold. (8:1-5, 6, 10)

On the basis of these beliefs, Hellenistic Jewish circles created a cosmic myth of Wisdom’s voyage through the world. At first she dwelled in heaven as God’s companion. Then, as the medium of his revelation, she entered the world in search of those who would receive her. Finally, rejected by mankind, she returned to heaven to take her place with God. We can see that threefold pattern in the following passage from the apocalyptic book of I Enoch, chapter 42:1-2:

_______[Preexistence]

Wisdom found no place

__in which she could dwell,

but a dwelling place was found for her

__in the heavens._______[Descent and rejection]

Then Wisdom went forth to dwell

__with the children of the people,

but she found no dwelling place._______[Reascent and exaltation]

So Wisdom returned to her own place,

and she settled permanently among the angels.

This is the pattern of descent and ascent (Greek: katabasis and anabasis) that Christianity took over and modified in order to express its belief that Jesus was the human incarnation of the divine savior who had preexisted from all eternity. In certain Jewish Diaspora traditions, notably in Philo of Alexandria, this heavenly Wisdom had become associated with the hypostatization of God’s “Word” or Logos, and even with an ideal heavenly Adam (not the Adam who fell into sin),

212

a “first man” who was sometimes described as neither male nor female, who was created in God’s image and dwelled with him in heaven. This Jewish tradition of Wisdom/Logos/heavenly Adam was adapted to fit Christianity’s new conviction that their savior had preexisted as God, had become incarnate as Jesus of Nazareth to save mankind from sin, and had reascended to his former divine station.

Although this cosmic redemptive drama had its roots in Jewish intertestamental literature, there is little doubt that the mission to the Gentiles was sensitive to the mood of the pagan world and adapted its message to the perceived religious needs of its new converts. Paul’s Epistle to the Philippians, written perhaps in the late fifties, contains an earlier Christian hymn (2:6-11) that expresses one version of the cosmic redemptive drama that Hellenistic Jewish Christians preached in the pagan world. Using Paul’s text in his Epistle to the Philippians, scholars have reconstructed the original, underlying Christian hymn about the savior as follows:

_______[Preexistence]

Though he was in the form of God,

__he did not count equality with God

__a thing to be clung to,_______[Incarnation]

but emptied himself,

__taking the form of a slave,

__being born in the likeness of men.And being found in human form,

__he humbled himself,

__and became obedient unto death._______[Exaltation and Universal Homage]

Therefore, God has highly exalted him,

__and bestowed on him the name

__which is above every name,that at the name of Jesus

__every knee should bow,

__in heaven and on earth and under the earth,

213

and every tongue confess

__”Jesus Christ is Lord”

__–to the glory of God the Father.

This hymn clearly shows how the Hellenistic Jewish Christians adapted and enhanced the Jewish Wisdom myth to fit the needs of their mission to the Gentiles. The modifications are visible in all three states of the redemptive cosmic drama.[18]

THE PREEXISTENCE OF THE SAVIOR: The hymn dramatically shifts the valence of christology by placing the work of redemption within the framework of a cosmic history that begins with the savior’s preexistence. To be sure, there are New Testament texts earlier than the hymn in Philippians which do speak of God “sending” the savior to earth (for example, Romans 8:3; Galatians 4:4), but those texts do not elaborate the preexistence of the savior, and in fact they are focused on the eschatological nature of his mission. In the Philippians hymn, however, the church’s original focus on the eschaton is entirely absent, and instead we are swept back in the other direction, to the beginning of God’s plan of salvation. Gone, too, is the simple “contrast model” of the early church, according to which God raised up the prophet whom men had rejected, and exalted him to his present reign in heaven. Here, rather, the drama of salvation begins outside of time, in heaven with an already enthroned divinity. The hymn transcends even the Jewish Wisdom tradition insofar as it declares the preexistent savior to be actually divine and equal to Yahweh (“in the form of God”) rather than merely a vague hypostatization of his being. However, while it is clear in the hymn that the savior existed in heaven before becoming a man, it is not stated that he existed prior to creation.

THE INCARNATION: Here the hymn takes a daring stride beyond the Wisdom myth. First, the divine savior is not “sent” by God, but freely and of his own accord chooses to leave his heavenly station. Second, and more important, this savior, unlike the Wisdom of late Judaism, empties himself (heauton ekenôsen) and becomes a specific, individual human being, Jesus of Nazareth. Such a self-emptying (kenôsis) and appearance in human form was unheard-of in the Jewish Wisdom tradition. The text in Philippians goes beyond the “conception christology”

214

of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, in which God makes a human child be the Christ from the first moment of his life. In this epistle we find a qualitatively different “incarnation christology,” in which a preexistent divine being becomes the Christ by becoming a human being. What is more, in becoming human the savior makes himself a “slave”–but not just God’s obedient prophetic servant of earlier christologies who “makes himself an offering for sin” (Isaiah 53:10). Rather, in the lexicon of pagan religions “slavery” meant the state of being subject to the supernatural demonic powers that ruled the “lower world.” Thus, according to the Philippians hymn, the savior descended from God’s heaven and not only took his place lower than the spiritual beings who rule the sky and the planets but also submitted, like any other human being, to their domination. Which means he submitted to the ultimate power of these forces of evil: He became obedient unto death.

EXALTATION AND UNIVERSAL HOMAGE: Here the hymn transcends the earlier enthronement christology of Hellenistic Jewish Christianity. In that second stage of christology, as we have seen, Jesus’ enthronement at God’s right hand had an element of provisionality about it: Jesus was already reigning, to be sure, but his full triumph still lay in the future, when God would completely submit the powers of the world to him. (“Sit at my right hand until I make your enemies your footstool,” Psalm 100:1). In the earlier “enthronement christology” we can still see a remnant of the Church’s original focus on a future parousia.

According to the Philippians hymn, however, Jesus received all power from the very moment of his reassumption into heaven after his crucifixion. After the savior’s death God “highly exalted” (hyperypsôsen) him, lifted him above the demonic powers to which he was formerly subjected. God took Jesus into the highest heaven, where he bestowed upon him the name which is above any other, the divine title “Lord.” The savior’s divine powers, which previously were hidden from the cosmic forces, are now fully revealed, so that enthroned on high, he commands worship from all three of the lower levels of the universe: “Every knee should bow, in heaven [the “air” ruled by demons] and on earth and under the earth.” God the Father now exercises his divine power toward the world through this exalted

215

God-man Jesus, who reigns as Cosmocrator, the Lord of the entire universe.

With the vision that is expressed in the Philippians hymn, belief in Jesus took a major step beyond earlier functional christologies and entered ontological christology. Jesus not only acted with divine power; he also was and is divine. This cosmic vision of the divine savior–preexistent, incarnate, and exalted over all the powers of the world–set christology on the high road along which it would continue to develop for the next two millennia.

We find further elaborations of this understanding of Jesus in later texts of the New Testament. The Epistle to the Colossians, for example, continues the adaptation of the Jewish Wisdom tradition when it speaks of the preexistent savior as “the image of the invisible God, the first-born of all creation” (1:15). He is the origin and sustainer of the cosmos; he is its head and it is his body. The present text from Colossians, like the Philippians hymn, does not assert that the savior existed with God before creation (rather, he is the “first-born” of creation). But in saying that Jesus was exalted as “the beginning [of the new creation], the first-born from the dead,” the text is asserting that Jesus is now the heir of God’s own powers:

_______[The first creation]

He is the image of the invisible God,

__the first-born of all creation.

For in him all things were created

__in heaven and earth,

__visible and invisible–

__whether thrones or dominions

__or principalities or authorities–

All things were created through him and for him.

He is before all things,

__and in him all things hold together._______[The new creation]

He is the head of the body, the church.

He is the beginning, the first-born from the dead,

__that in everything he might be preeminent.

In him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell,

216

and through him to reconcile all things to himself,

__whether on earth or in heaven,

__making peace by the blood of his cross. (Colossians 1:15-20a)

This New Testament christology of the divine savior achieves its highest expression in the hymn to the preexistent and incarnate savior that serves as the prologue to the Gospel of John.[19] That hymn is older than the Gospel itself (which was composed during the last decade of the first Christian century) and draws upon the Jewish Wisdom tradition at that point in Hellenistic Judaism where Wisdom had already come to be combined with another hypostatization of Yahweh: his Word (Greek Logos). In fact, it is possible that the prologue-hymn is a combination of a Jewish hymn to Wisdom-Logos (roughly, verses 1-12) and a specifically Christian hymn (verses 14 and 16) about the incarnation of the savior. (The final editor of the Gospel inserted into the combined hymns a number of verses that are not relevant to this discussion and that are omitted below.)

Unlike Colossians, which speaks of the savior as the first-born of all creation, the prologue to John’s Gospel pushes the existence of the Word back to a point even prior to creation.

In the beginning was the Word,

And the Word was with God,

And the Word was God.

He was in the beginning with God. (1:1-2)

Unlike the Wisdom of late Jewish tradition, this Word, or Logos, is not merely a hypostasis of one of God’s attributes, but rather exists in his own right as God and with God. Although there is no mention here of the Trinity–Father, Son, and Holy Spirit–the text is certainly on the way to that later doctrine.

Like the Wisdom of the Jewish tradition, this Word is the agent of all of God’s creation:

All things were made through him

__and nothing that has been made

____was made without him. (1:3)

217

And also like Wisdom, the Word is the mediator of God’s revelation to the world. Even before he becomes incarnate as a man, the Word shines into the world as God’s light. We notice here the same pattern as Wisdom’s odyssey through the world, with rejection by some and acceptance by others:

In him was life,

__and the life was the light of men.

And the light shines in the darkness

__and the darkness has not overcome it.He was in the world

__yet the world knew him not.

He came to his own

__and his own received him not.

But to all who received him

__he gave power to become children of God. (1:4-5, 10-12)