The First Coming: How the Kingdom of God Became Christianity (1986–electronic edition 2000)

Thomas Sheehan

I

How Jesus Lived and Died

In popular Christian teaching, Jesus often comes across as a divine visitor to our planet, a supernatural being who dropped into history disguised as a Jewish carpenter, performed some miracles, died on a cross to expiate sins, and miraculously departed again for the other world.

In official Church teaching this view of Jesus as a god who merely pretended to be human is a heresy, and the seriousness of the error is not mitigated by the fact that multitudes of the faithful, from catechists to cardinals, firmly believe and teach it. In earlier forms the heresy was called “Docetism” (from the Greek verb dokei, “he only seems to be”), and it has been condemned many times for maintaining, in effect, that Jesus merely appeared to be a human being but actually was not, that this heavenly savior merely “wore” flesh like a garment while he went about his divine task of redeeming the world. Church condemnations notwithstanding, this heresy continues to thrive in contemporary Christianity and remains one of the more common forms of christology in popular Roman Catholicism.[1]

But even in its official, orthodox form, Christianity tends to overlook

32

the fact that, exceptional though he proved to be, Jesus was a young Jewish man of his times, as mortal and fallible as anyone before or after him. Whether this Galilean carpenter was also God is a matter of some debate. But no serious person doubts that he in fact lived as a human being in a certain place and at a certain time. Which means that one way to make sense of who he was and what he was about is to “materialize” him, to pull him out of his mythical eternity and reinsert him into the historical situation that shaped his mind and his message.

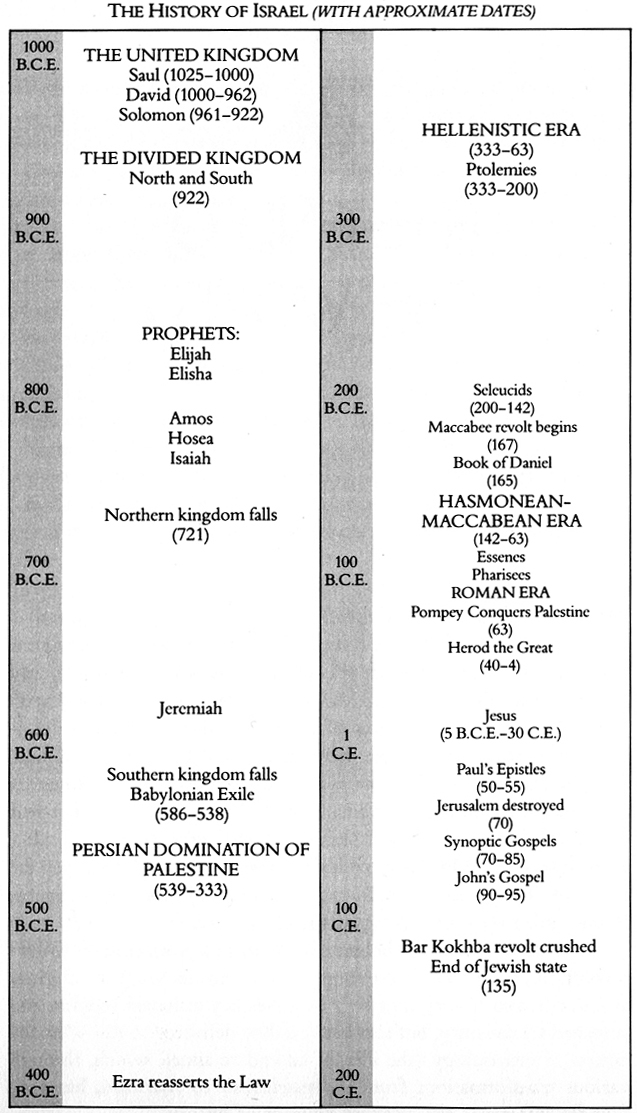

Jesus lived his brief and tragic life (from about 5 B.C.E. to 30 C.E.) at a time when Judaism was undergoing dramatic transformations in its social and political structures, and attempting to interpret Jesus in abstraction from that context would be like trying to make sense out of Dante without referring to medieval Florence. Therefore we begin the present chapter, which is devoted to understanding Jesus’ message of the “kingdom of God,” with some remarks on the historical development of Israel and, in particular, on the eschatological mood of the times.

33

1. The End of the World

The years during which Jesus preached–probably 28-30 C.E.–were moments of relative calm at the eye of a political hurricane. Two hundred years earlier, the Maccabee brothers had revolted against Syrian domination of Judea, and after a long struggle, the Jewish people had won a brief hiatus of independence from foreign domination (142-63 B.C.E.). Those years of political freedom ended with Pompey’s conquest of Palestine, and thereafter the country lived under the cloud of an uneasy Pax Romana that held until 66 C.E. In that year Jewish revolutionaries, called Zealots, rebelled against the empire; but Roman legions led by Titus crushed the insurrection and destroyed the Jerusalem Temple in 70 C.E. In 135 C.E. a second Jewish revolt against Rome ended with the razing of the Holy City.[2]

Those three hundred turbulent years, framed at both ends by violent revolutions, mark one of the most creative eras in Western religious and intellectual history, not only because they reshaped Judaism and launched Christianity, but also because they delivered to the West the notion of eschatology (the idea of an end to time), which, through various transformations from millenarianism. to Marxism, has profoundly influenced the Western concept of history.

34

35

What interests us about this axial period are the changes it engendered in Jewish religious consciousness just before and during Jesus’ lifetime. One of the major accomplishments of the period was a radical shift in the Jewish conception of history and the emergence of an intense and pervasive expectation of “the end of the world.” This eschatological mood dominated Jesus’ lifetime and affected how people heard his message. Let us see how it came about.

FROM HISTORY TO THE LAW

The Jewish prophets who flourished before the Babylonian Exile (586-538 B.C.E.) had no clear doctrine of an end of time and certainly no hope that God would one day destroy the world. Rather, the uniqueness of the prophets’ message lay in their insistence that history was the arena of God’s salvation of Israel.[3]

Unlike many other religions, which located the manifestations of the divine in the mythical dawn of time or in the eternal cycles of nature, pre-exilic Judaism proclaimed that the realm of human action was the place where God revealed himself. Yahweh was a God of history who intervened on Israel’s behalf through such concrete events as the Exodus, the conquest of Palestine, and the establishment of the Davidic kingdom. Israel’s God was a political activist who established her rulers, toppled her enemies, and passed historical judgment on her good and bad actions. Long before Christians discovered Marx, the prophets preached a form of “liberation theology”: faith as cooperation with God’s intention to effect worldly justice, and peace for mankind. Prophetism was an act of faith in the God of history.

Before the exile the Jews saw time as neither linear nor cyclical, neither teleological nor eschatological, but as epiphantic, the medium of God’s revelation to and salvific presence with Israel. This faith that God was directing history (along with the later belief, derived from it, that he had created the world) prevented traditional Judaism from looking ahead to an apocalyptic end of history followed by a suprahistorical “new heaven and new earth.” The classical prophets of the seventh and eighth centuries B.C.E. were neither pessimistic about history’s

36

course nor optimistic about transcending it, for theirs was a historical rather than an otherworldly hope. When Israel was beset by political and social sufferings, the prophets promised salvation not as a second life in the hereafter but as a temporal restoration of the nation under a future Davidic king. Salvation was not an escape from time through resurrection of the body or immortality of the soul, but a triumph within time in the form of peaceful social existence in a theocratic state.

But all that changed with conquest of the kingdom of Judah by Nebuchadnezzar in 586 B.C.E. and the subsequent exile in Babylon. When the Jewish people began returning to Palestine in 538 B.C.E. after a half century in captivity, they were allowed only limited political autonomy under Persian rule and, later, under Greek and Syrian domination. Deprived of her Davidic leaders and major prophets, Israel began to find her spiritual anchorage less in Yahweh’s direction of her national history than in the revealed words of Scripture. But now the Bible was read not so much as an account of the gesta dei, God’sinterventions in Israel’s past as a promise of further epiphanies to come. Rather, the emphasis was on the Law, which they thought had been given by God in the past and remained ever valid for the present, seemingly without the need of God’s further interventions in time. This shift from history to hermeneutics, from faith in God’s direction of history to scrupulous interpretation of legal codes, provided Israel with a tidier, if less dramatic, world.

For the next three and a half centuries Israel was a kingless theocracy governed by a timeless Law. Around 400 B.C.E., under the high priest Ezra (“a scribe skilled in the law of Moses,” Ezra 7:6),[4] the five books of the Pentateuch, called the Torah, or Law, were edited in their final form and became the religious and legal constitution of the Jewish people.[5] Henceforth the guides of Israel would no longer be the prophets, who in pre-exilic times had called for fidelity to God’s workings in history, and certainly not the Davidic kings, who were no more. Rather, her political and religious leaders would be the priests of the rebuilt Temple, the rabbis of the local synagogues, and in particular the scribes, the theological lawyers who delivered the casuistic and devotional embellishments on the Law that would eventually evolve into the Talmud.[6]

37

The Law, the index of Israel’s fidelity to the Lord, became a complicated body of codes.[7] It was divided into the Written Law, or Torah (torah she-biktab), whichGod had delivered to Moses–that is, the Ten Commandments plus the myriad supplementary prescriptions found throughout the Pentateuch–and the Oral Law, or “Sayings of the Fathers,” the hundreds of legal principles and devotional or ethical interpretations that were generated by the scribes from the fourth century B.C.E. onward as guiding rules for faithful Jews and that eventually became codified as the Mishnah and the Gemara.

The purpose of the casuistic Oral Law was, as the scribes put it, to “build a fence around the Torah,”[8] a bulwark of detailed codes which, if properly observed, would guarantee that the scrupulous believer could not have violated the Written Law. (Wearing a false tooth, for example, might constitute carrying a heavy burden and thus violate the commandment of Sabbath rest, whereas pulling a mule from a pit might not.[9]) This elaborate “second Pentateuch,” combined with the already elaborate set of forty-one laws found in the Covenant Code (Exodus 20:23-23:33), plus the seventy-eight laws of the Deuteronomic Code (Deuteronomy, chapters 12-26), and the strict regulation of sex, feasts, and sacrifices in the Holiness Code (Leviticus, chapters 17-26), often gave the impression of a jurisprudential nightmare. And the laws kept growing until, according to one tradition: “Six hundred and thirteen commandments were communicated to Moses, three hundred and sixty-five prohibitions, corresponding to the number of days in the solar year, and two hundred and forty-eight positive precepts, corresponding to the number of the members of man’s body”[10]–these hundreds of statutes at the service of defining the ten rather simple commandments revealed to Israel through Moses.

Moreover, by the time of Jesus Judaism was divided by sectarian debates over the question of which Law was to be observed. The conservative and aristocratic Sadducees were rigid literalists who observed only the ancient Written Law, whereas the fervent lay sect of the Pharisees, who were aligned with the scribes, were considered “liberals” because they not only followed the ancient Torah but also observed and developed the more recent Oral Law with its scrupulous attention to everyday life. The Pharisees of Jesus’ day, who were greatly respected by the ordinary people, were in turn divided into the

38

strict constructionists of the Shammai school and the more flexible adherents of the Hillel school. When we read in Mark’s Gospel that the Pharisees approached Jesus with a question about the grounds for a legal divorce (10:1-12), we are witnessing an effort to get him to take a side in the debate between these two Pharisaic sects. The attempt, in fact, was unsuccessful, and as we shall see, much of the radical newness of Jesus’ message consisted in his proclamation of a nonlegalistic relation to God.

In short, the period during and after the exile witnessed a major transformation in consciousness within Israel: a shift from history to hermeneutics, from a prophetic engagement with political events to a clerical exegesis of the Law. A historical contrast suggests itself here. The classical Greeks, in their confrontations with the Persian Empire from the battle of Marathon in 490 B.C.E. through the conquests of Alexander 150 years later, were led in a sense from religion to history, from mythical scripture (in their case, Homer) to political action. At roughly the same time Israel, reeling from her defeat by Babylon and humbled by her subjection to Persia, retreated from history to Scripture, from political action to religious legalism. As these two very different cultures collided with the empires of the Middle East, their paths took opposite directions. Greece, feeling its historical power, pushed beyond itself and became the worldwide cultural force of Hellenism. Israel, feeling its political impotence, turned within and became, for the first time, an institutionalized “religion.”

THE BIRTH OF ESCHATOLOGY

Along with this post-exilic emphasis on the Law there went a transformation in the Jewish conception of Yahweh and his relation to his chosen people. Before the captivity in Babylon, Israel envisioned God’s salvation as a future restoration of the glorious past under a new Davidic king. But after the exile, when Yahweh seemed to have fled to the higher heavens, leaving priests and scribes in his wake, the earlier hope for this-worldly theocratic restoration began to fade. Yahweh came to be seen less as the national deity who had intervened and would intervene again in Israel’s political history, and more as an Oriental despot who ruled the entire universe, including the Gentile

39

nations, from the distant and impersonal heights of metaphysical transcendence. From those heavens he governed the world no longer by direct historical intervention as in the past, but by the ministrations of angelic mediators who, like the eternal Law, mediated his presence to mankind.

Israel’s retreat from history took a dramatic step in the second century B.C.E. with the emergence of the radically new idea of eschatology, the doctrine of the end of the world. At the beginning of the Maccabean revolt, when Israel’s fate seemed to be at its lowest point, pious Jews began to hope not for a new divine intervention within history but for a catastrophic end to history, when God would stop the trajectory of Israel’s decline by destroying this sinful world and creating a new, supratemporal realm where the just would find their eternal reward.[11]

This eschatology, or doctrine of the end of time, found literary expression in the imaginative and very popular genre of apocalypse, in which pseudonymous authors spun out fanciful predictions of the coming end of the world and dramatic descriptions of the aftermath. Apocalyptic eschatology spelled the end of the prophets’ hope for a future revival of the past and replaced it with mythical hopes for a cosmic cataclysm followed by the eternal olam ha-ba, the “new age to come.” If prophetism had been an act of faith in God’s workings in history, apocalyptism was an act of despair.[12]

This recasting of Yahweh as apocalyptic destroyer was strongly influenced by the Zoroastrian religion that the Israelites had encountered during the Babylonian Exile. Zoroaster (ca. 630-550 B.C.E.) had taught that the world was the scene of a dramatic cosmic struggle between the forces of Good and Evil, led by the gods Ormazd and Ahriman. But this conflict was not to continue forever because, according to Zoroastrianism, history was not endless but finite and in fact dualistic, divided between the present age of darkness and the coming age of light. Time was devolving through four (or in some accounts seven) progressively worsening periods toward an eschatological cataclysm when Good would finally annihilate Evil and the just would receive their otherworldly reward in an age of eternal bliss. Zoroastrianism’s profound pessimism about present history was thus answered by its eschatological optimism about a future eternity.

As Israel’s political fortunes faded and as such Zoroastrian ideas as

40

these took hold, Judaism shifted the focus of its religious hopes from the arena of the national and historical to that of the eschatological and cosmic, from political salvation in some future time to preternatural survival in an afterlife. This radical change can be seen in late Judaism’s adoption of notions like the fall of Adam from paradisal grace at the beginning of time, the workings of Satan and other demons in the present age, and the Last judgment and the resurrection at the end of history–all of which Christianity was to take over and turn into dogmas. But the clearest sign of this absorption of Persian ideas can be found in the eschatological visions of history that surfaced in apocalyptic literature during the two centuries before Jesus began to preach.

One such apocalyptic work was the Book of Daniel, composed around 165B.C.E. during the Maccabean revolt against the oppressive Seleucid dynasty. The tyrannical King Antiochus IV, who ruled Palestine (175-03 B.C.E.) from Syria, had undertaken to force Hellenistic religion and culture on his Jewish subjects. He deposed the legitimate high priest, forbad ritual sacrifice and circumcision, plundered the Temple treasury, and, most shocking of all, set up the “Abomination of Desolation” (Daniel 11:31),an altar to Olympian Zeus, within the Temple precinct.

The Book of Daniel was written by an anonymous author in the second century B.C.E.; but in a way typical of apocalyptic works, the book purported to have been composed some four centuries earlier by a prophet named Daniel, and pretended to predict the catastrophic events that in fact were happening in the author’s own lifetime. The work interpreted these events as “eschatological woes,” a time of sufferings and troubles “such as never has been since there was a nation” (12:1). According to God’s hidden plan, these woes marked the final stage before the destruction of the old and godless world and the final triumph of divine justice.

The Book of Daniel envisaged history as rushing downhill toward its eschatological end, which the author was convinced would come in his own lifetime. For example, the book told of a dream that the sixth-century Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar supposedly had and that the prophet Daniel interpreted for him in terms of the succession of kingdoms (2:31-43). In the dream history was depicted as a giant

41

statue with the head made of gold (representing the kingdom of Babylon), the chest and arms of silver (the kingdom of the Medes), the belly and thighs of bronze (the kingdom of Persia), the legs of iron (the empire of Alexander), and the feet made partly of iron and partly of clay (the divided kingdom of the Seleucids in Syria and the Ptolemies in Egypt). In the dream

[a stone] smote the image on its feet of iron and clay, and broke them in pieces; then the iron, the clay, the bronze, the silver, and the gold, all together were broken in pieces, and became like the chaff of the summer threshing floors. (2:34-35)

The prophet Daniel predicted that when the Seleucid kingdom crumbled–as the author of the book believed was happening in his own day–the end of time would come. But before that, Israel had to pass through a time of eschatological woes when the final godless kingdom would “devour the whole earth, trample it down and break it to pieces” (7:23).At the climax of these sufferings a Great Beast–in this case the Seleucid king Antiochus IV–was to appear and “speak words against the Most High and wear out his saints” (7:25).[13]

According to Daniel the duration of these eschatological woes was limited, and at the end of this period God himself would arrive as the cosmic judge to annihilate the kingdom of the beast and to “set up a kingdom which shall never be destroyed” (2:44). The apocalyptic writer describes his vision of the imminent eschaton:

As I looked, thrones were placed, and one that was ancient of days took his seat. … The court sat in judgment and the books were opened. … And as I looked, the beast was slain, and its body destroyed and given over to be burned with fire. (7:9-11)

At the climax of this apocalyptic drama a mysterious figure, “one like a man,” appears from the heavens. This figure assumes the role of God’s viceregent and ushers in the new and eternal kingdom.

And behold, with the clouds of heaven there came one like a man, and he came to the Ancient of Days and was presented before him.

42

And to him was given dominion and glory and kingdom, so that all peoples, nations and languages should serve him. His dominion is an everlasting dominion, which shall not be destroyed. (7:13-14)

This strange eschatological figure, who came to be called “the Son of Man,” has been the subject of much scholarly debate.[14] One plausible hypothesis explains him as a collective symbol of the Jewish people themselves, represented in the form of an angel (“one like a man”) whom God had appointed as Israel’s protector and advocate in God’s sight. However, later (probably in the first century B.C.E.) this collective symbol of Israel became concretized as a specific individual savior who was expected to descend from heaven at the end of time. Apocalyptic writers took the phrase from the Book of Daniel (“one like a man”) and turned it into an eschatological title: “the Son of Man.” For example, the First (Ethiopic) Book of Enoch 46(ca. 100 B.C.E.?) interprets this savior as having existed from all eternity, hidden in God’s presence since before the creation. The apocalyptic visionary, swept up to heaven and to the beginning of everything, writes:

At that hour, that Son of Man was given a name in the presence of the Lord of the Spirits, the Before-Time, even before the creation of the sun and the moon, before the creation of the stars, he was given a name in the presence of the Lord of the Spirits. … He is the light of the gentiles and he will become the hope of those who are sick in their hearts. … He became the Chosen One; he was concealed in the presence of the Lord of the Spirits prior to the creation of the world, and for eternity. And he has revealed the wisdom of the Lord of the Spirits to the righteous and the holy ones. (48:2-7a)

Made manifest only at the end of time, this Son of Man would save God’s chosen people, pass judgment on the Gentile kingdoms, and preside over the eschatological banquet in the new world.

Moreover, along with these otherworldly hopes there also arose, for the first time in Judaism, the expectation of a resurrection of the dead and personal survival in an afterlife.[15] Earlier predictions of “resurrection” in the writings of the prophets had been only figurative and

43

metaphoric. For example, in the preapocalyptic Book of Ezechiel, which dates from the time of the exile, God promises Israel, “I will open your graves and raise you from them” (37:12).But this promised “resurrection” was merely a symbol of Israel’s eventual return from the Babylonian Exile to the very concrete and this-worldly land of Palestine, as the continuation of the passage shows: “You shall live, and I will place you in your own land” (37:14).However, in the apocalyptic Book of Daniel resurrection was promised not as a metaphor for future political restoration but quite literally as the otherworldly reward of the just at the end of time:

And many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt. (Daniel 12:2)[16]

As we shall see, the elements of this stock apocalyptic scenario–the predicted period of eschatological woes, the cosmic collapse, the coming of the Son of Man, the divine judgment and reward–were known to Jesus. But strictly speaking, Jesus was not an apocalyptist at all. He was very restrained in his appeal to apocalyptic imagery and, when he used it, always adapted it to his very different message.

THE COMING SAVIOR

The historical event that most determined Judaism in the two centuries before Jesus was the successful Maccabean revolt (167-142B.C.E.) against Syrian domination of Palestine. Outraged by the sacrileges of King Antiochus IV, the brothers Judas, Jonathan, and Simon Maccabee each in turn led the struggle against Seleucid tyranny, until Simon finally won freedom for Palestine. The result was a brief parenthesis of Jewish self-rule that lasted until the Roman conquest of the land in 63 B.C.E. What is more, the establishment of the new kingdom led to a radical shift in the Jewish concept of the promised Davidic messiah.

The triumph of the Maccabees was their undoing. While all Jews

44

were happy to be a free people again, many of the more pious resented the fact that the new Hasmonean-Maccabean dynasty was not descended from King David. On religious grounds, therefore, this new regime could not be the kingdom promised by the prophets, and no Maccabee could be the true messiah. Not only that, but many found it intolerable that both Jonathan and Simon Maccabee had dared to make themselves high priests without being descended from the proper sacerdotal line of the ancient high priest Zadok (I Kings 1:26, 11 Samuel 8:17), whose family had held the office since the tenth century.[17] On two counts, therefore, Jonathan and Simon Maccabee were at fault. Neither Davidic nor Zadokite by descent, they seemed to be power-hungry interlopers in both the political and religious realms.

Opposition to the Maccabees ran high among their fellow Jews, and in particular the question of the proper bloodline of the high priesthood became the flashpoint of a religious revolt against the dynasty. One of the most important of the protesting groups was the devout lay sect of the Pharisees (Hebrew perushim, Aramaic perishayya, “Separated Ones”), who were later to figure so prominently in Jesus’ ministry. They broke with the Hasmonean-Maccabean regime in 134 B.C.E. and proclaimed their hope for an ideal, non-Hasmonean king. This new messiah not only would be descended from David and therefore anointed as God’s deputy but also–here was the radical shift–would have two new characteristics. First, he would be designated ruler of the entire world and not just of Israel; and second, he would arrive at the imminent end of the world. The messiah whom the Pharisees proclaimed was to be no longer a national king but a universal emperor, no longer a historical figure but an apocalyptic phenomenon.[18]

The absolute novelty of this idea of an eschatological emperor-messiah can be seen by contrasting it with earlier, more modest conceptions. Before the Babylonian Exile the term “messiah” (“anointed one”) had none of the supernatural connotations that later generations of Jews and Christians would give it. Originally the word designated any Davidic king before the exile. He was a political and military leader, a man who lived in the flesh and was as mortal as any other human being. But Jews also believed that the king was the chosen agent

45

of God’s will on earth, and as a sign of that election he was anointed with oil either by a prophet or by a priest (I Samuel 10:1, 16:13; 1 Kings 1:39). When the ruler was anointed (and so became “messiah”), he was constituted the adopted “Son of God.” We see this, for example, in Psalm 2:7, where Yahweh says to the king on coronation day, “You are my son, today I have begotten you.” The title “Son of God” did not indicate that the king was ontologically divine but only that he was God’s special agent on earth. Even during the difficult years surrounding the Babylonian Exile, when prophets projected an ideal future messiah-king and named him “Wonderful Counselor, Almighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace” (Isaiah 9:6), the reference was to a mortal human being, the national political leader in his unique theocratic role as God’s worldly deputy.

The messiah of the Pharisees, for all his uniqueness as a universal and eschatological ruler, did in fact absorb and continue some of the national-historical traits of the traditional messiah. In the popular imagination the traditional national king now tended to become an idealized, even mythologized, ruler who, while certainly Davidic in descent, would be not just one more king in that line but the final and universal sovereign who would bring about God’s definitive reign throughout the entire world. But conversely, for all these “transcendent” qualities, this eschatological world-emperor was still seen as a human and historical king and not as a supernatural being who would descend from heaven. In other words, as much as the new savior’s eschatological features drew on the otherworldly spirit of apocalypse, his specifically messianic role anchored him squarely in the earthly order. The point is that his messiahship now had both universal political scope (since he would have dominion over all nations, not just Israel) and definitive religious significance (since he would appear at the end of time).

The Pharisees’ new concept of the messiah was only one of the changes in Judaism that resulted from religious opposition to the Hasmonean-Maccabean dynasty. Another came from a group that was spiritually even more radical and in fact the first sect to break with the regime: the Essenes. Led by a charismatic Zadokite priest of Jerusalem who is

46

known to us only as the Righteous Teacher, the Essenes were implacably set against the Hasmoneans’ usurpation of the high priesthood. Around 142 B.C.E. they made a clean break with the Temple priesthood and trekked into the wilderness to found the monastic community of Qumran. This was the settlement whose eschatological doctrines and life-style came to light only in 1947with the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls.[19]

Like the Pharisees, the Essenes were eschatologists, but rooted as they were in a sacerdotal tradition, they looked forward to a priestly rather than a political messiah. They maintained that their leader, the Righteous Teacher, was not the awaited messiah-priest but only a living sign that the world had entered upon its last days. They expressed their belief in the imminence of the eschaton not only by their cultic communism and (for some members) religious celibacy but also by the eschatological meal of bread and wine that they celebrated, almost like a pre-Christian Eucharist, in anticipation of the coming messianic banquet.

The death of the Righteous Teacher around 115 B.C.E. fed the Qumran community’s hope for the end of the world and the appearance of a priestly savior who would be anointed by God. This hope was both increased and transformed around 110 B.C.E. when large numbers of Pharisees, who were fleeing persecution by the Hasmoneans, flocked to the desert community and brought with them their expectation of a cosmic political messiah. As a result, in the decades before Jesus the Qumran community came to expect two eschatological messiahs, one a high priest descended from Aaron and the other a world-emperor descended from David. Scriptural grounds for this dual messiahship were educed from an obscure passage in the prophet Zechariah which mentioned “two anointed ones who stand by the Lord of the whole earth” (4:14).

As if this syncretistic doctrine of a messiah-priest and a messiah-emperor were not enough, yet another expectation swept through Judaism at this time: the hope for an eschatological prophet whowould appear shortly before the end of the world.[20] This popular idea grew up independent of Davidic messianism and took two distinct forms.

47

On the one hand there was the expectation of a nonnationalistic, nonmilitaristic messianic “prophet like Moses” who had been promised in the book of Deuteronomy. There Moses told the Israelites of a revelation he had had:

The Lord said to me:

“I will raise up for them a prophet like you from among their brethren, and I will put my words in his mouth, and he shall speak to them all that I command him.” (18:15)

On the other hand many Jews expected the return of the prophet Elijah, who had been swept up to heaven in a chariot eight centuries earlier (II Kings 2:11-12) and who, it was believed, would reappear toward the end of time to prepare Israel for God’s judgment. A verse of the prophet Malachi, adapted to correspond to this hope, was often cited:

Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the great and terrible day of the Lord comes. And he will turn the hearts of fathers to their children and the hearts of children to their fathers, lest I come and smite the land with a curse. (4:5 = 3:23)

In short, the years before Jesus’ birth witnessed an explosion of apocalyptic hopes for an imminent end of the world, and the popular religious imagination tended to multiply eschatological figures. (1) The traditional hope for a national king of the Davidic line who would restore the kingdom of Israel rubbed shoulders with (2) the new expectation of a supranational Davidic savior. But the latter in turn could be either political or sacerdotal, an imperial theocrat or a supreme high priest–or both ruling together. And before his coming there might arrive (3) a final, or eschatological, prophet–whether a Moses-like figure who would give a new Law or Elijah redivivus, who would prepare Israel for God’s coming. Moreover, all of these figures tended to take on one another’s traits and often to blur into one another in a complex spectrum of awaited saviors.

It was an apocalyptist’s dream, frequently confusing but burning with hope and with heightened expectation that something momentous

48

was soon to happen. What is clear is this: If a sensitive and deeply religious Jewish man felt called to be a reformer of Israel, a prophet who would galvanize his people with hope that God was coming soon to save his chosen faithful, and if per impossible he could have picked the place and time of his birth so as to facilitate his mission, he could hardly have chosen a better place than Palestine around the year 3755 of the Jewish calendar.

49

2. The Making of a Prophet

The scene unfolded near the mouth of the Jordan River late one afternoon two millennia ago. According to today’s calendar the year was 28 or 29 C.E.; according to Jewish reckoning, it was the 3788th year since the creation of the world.[21]

The place is an inhospitable wilderness, its barrenness relieved only by the muddy river, winding its way south to the Dead Sea. A crowd of men and women, simple people, are listening intently to a strange figure, wiry and ascetic, dressed in rough animal skins and rumored to subsist on nothing but the wild honey and locusts he finds in the desert. His name is John, and he is a pious Hasidic Jew preaching the impending judgment of God.[22] He calls for conversion, and his message is fraught with urgency:

Even now the axe is laid to the root of the trees. Every tree therefore that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire. (Matthew 3:10)

He practices a baptism of repentance for sin, as do the Essenes of nearby Qumran, with whom he may once have been associated. But

50

whereas the Essenes invite their disciples to carry out their own ablutions, John himself performs the ritual washing on his followers and so earns the title “the Baptizer.” His impact is tremendous. The Gospel says that multitudes went out into the desert to hear John’s message and receive his baptism.

And the people were in expectation, and all men questioned in their hearts concerning John, whether he might be the messiah. (Luke 3:15)

Imagine a young man, just over thirty years of age, who is walking by the river that afternoon. He was baptized by John some time before and is now a member of his inner circle. Perhaps he is even one of the assistants who help the Baptizer in his ritual. John notices him and points him out to two of his disciples, and these disciples, shyly but with deep interest, proceed to follow the young man at a distance.

Jesus turned and saw them following, and he said to them, “What do you seek?” They said to him, “Rabbi, where do you dwell?” He said to them, “Come and see.” They came and stayed with him that day, for it was about the tenth hour. (John 1:38-39)

“Rabbi, where do you dwell?”[23] It is impossible to know if this is exactly what happened that afternoon when the “Jesus-movement” is supposed to have been born out of that question. The scene sketched above is a composite, drawn from the four Gospels, each of which had a theological rather than a historical point to make about Jesus and John the Baptist. But historical or not, the story about the encounter of Jesus and his first disciples is true in its own way, for it contains in nuce the entire Christian experience: a mood of expectation, an earnest seeking, an exchange of questions to which no real answers are given, only the invitation to “come and see,” indeed to see not who Jesus is so much as where and how he dwells .

The purpose of this chapter is not to produce a psychobiography of Jesus. The evidence for that is lacking. Rather, I am attempting, in part by means of an imaginative reconstruction, to relate the core of

51

historical facts that contemporary scholars have managed to establish about the life of Jesus and, in what immediately follows, about his relation to John the Baptist. Many years after Jesus died, his Christian followers would attempt to resolve the rivalry between their sect and John’s by interpreting the Baptist as a forerunner of Jesus. Indeed, Luke in his Gospel devised a family relation between the two and arranged their conceptions in such a way that even before they were home John was a precursor of Jesus. Luke went so far as to have the prenatal Baptist “leap in the womb” at the presence of the unborn Jesus when their pregnant mothers met (1:36 and 44).

But that legend, like the inspiring but unhistorical story about the miraculous virginal conception of Jesus, is a theological interpretation created some decades after the death of Jesus to express Christianity’s faith in his special status. In fact we know next to nothing about either John or Jesus before their meeting on the banks of the Jordan. But we can establish what they were about from then on, that is, in the scarce two years that both of them had left to live.

Where, then, did Jesus dwell? This question goes to the essence of his prophetic mission: what he taught, how he lived, who he thought he was. But Jesus’ ideas, life-style, and self-understanding did not emerge from his consciousness ready-made. He developed them, as any human being does, in interaction with his environment and his contemporaries. To begin with, his encounter with John the Baptist had an important, if often overlooked, influence on Jesus’ religious thinking, and so before taking up questions about his message (what he taught), his manner (how he lived), and the man himself (who he claimed to be), we shall begin by asking about his meeting with John at the Jordan.

Some might object that the following sketch of that meeting delves further into Jesus’ psychology than the evidence will support–and that is true; others may claim that it does not portray Jesus for what he really was: an omniscient God who only “submitted” to John’s teachings and baptism to set an example of how others should act–but that is not true. Whether his meeting with the Baptist planted the seed of Jesus’ vocation as a prophet or whether he had already conceived his mission privately and merely came forward publicly with his baptism in the Jordan, we cannot know. But the best evidence

52

shows that the encounter with John was a spiritual awakening for Jesus. How, then, did it come about and what effect did it have?

Jesus most likely was born not in the southern town of Bethlehem but in Nazareth, a village in the northern province of Galilee, the first child of a carpenter named Joseph and his young wife, Miriam or Maria. When his father had him circumcised at the local synagogue, he named him after Moses’ successor, Joshua, in Hebrew Yehoshua (“Yahweh helps”), which in those days was usually shortened to Yeshua or even to Yeshu, which is how he was popularly known. When he grew up he followed his father’s woodworking trade, as no doubt his younger brothers, James, Judas, Simon, and Joses, also did (Mark 6:3).[24]

But as the fame of the Baptizer spread even to his obscure village, the young man Jesus, after his father had died, left Nazareth for the Jordan valley. There, like many others, he was profoundly gripped by John’s grim message of doom and his call for repentance.[25] It was not enough, Jesus heard, to be a child of Abraham, a son of the Covenant sealed with circumcision. It did not suffice to obey the Law and honor Yahweh with one’s lips. The heart had to change. When the respected Pharisees and Sadducees, the pillars of Judaism, came to the Jordan to hear what the Baptist was preaching, Jesus was struck by how John railed at them for their smugness:

You brood of vipers! Who has warned you to flee from the wrath to come? Bear fruit that befits repentance, and do not presume to say to yourselves, “We have Abraham for our father.” For I tell you that God is able from these stones to raise up children to Abraham! (Matthew 3:7-9)

Jesus was also impressed by the fact that John, unlike the apocalyptic preachers so popular in those days, preached no messiah, proclaimed no end of the world, and promised no future aeon of bliss. He appealed to no signs of the alleged cataclysm to come and made none of the fantastic predictions that were the stock in trade of the apocalyptic writers. His message was simple and bare: The judgment is coming now, not in some distant future, and rather than being played out on

53

the stage of world history with cosmic inevitability, it cuts to the inner core of the individual and demands personal decision.

To be sure, John often preached in eschatological terms. He spoke, for example, of “one who is coming” (he may have meant the “Son of Man,” although he kept the reference vague), and he warned of eschatological fire.[26] But it was an eschatology without apocalyptic trappings, an existential crisis of imminent, definitive judgment with none of the wildly dramatic stage props of the apocalyptic scenario. The fire he spoke of was not a cosmic conflagration but a flame that sears to the heart of a person, enlivening the humble and damning the unrepentant:

I baptize you with water for repentance, but he who is coming after me is mightier than I, and I am not worthy even to carry his sandals. He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and with fire. His winnowing fork is in his hand, and he will clear his threshing floor and gather his wheat into the granary, but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire. (Matthew 3:11-12)

It was the message of a prophet, not an apocalyptist, and like the ancient prophets, John called for radical acts of justice and charity as the fruit of faith and repentance. When the people asked him what they must do to turn to God, John demanded not prayer or rituals but deeds. “He who has two coats, let him share with him who has none, and he who has food, let him do likewise.” To the tax collectors who came for baptism he commanded, “Collect no more than is appointed you.” And to soldiers, “No intimidation! No extortion! And be content with your pay” (Luke 3:10-14).

Jesus, we may imagine, was pierced to the heart. He repented and was baptized.

To accept John’s message and enter his community meant to break in some degree with the prevailing religious orthodoxy. In John’s day Judaism, like Christianity today, was in profound crisis, and the Baptist deepened the sense of uncertainty. By his time the brief parenthesis of freedom brought by the Maccabees (142-63 B.C.E.) had long since been closed, and Palestine was once again subject to foreign domination, this time under the Romans. So too the ancient form of faith in Yahweh

54

was gone. In place of the old hopes for renewal within history there now stood apocalyptic expectations of an end of the world; and instead of attentiveness to the prophets’ call for justice there prevailed scrupulous observance of the Law. The two went hand in hand: Apocalypse promised Israel salvation at the cosmic level, and adherence to the Law guaranteed that she would make it through the coming judgment unscathed.

All of this John called into question. First, the eschatological judgment he preached was directed against Israel, not her enemies. Whereas the apocalyptic writers foretold destruction of the Gentiles and vindication of the chosen people, John turned the knife against the very members of God’s Covenant: the eschaton was as threatening to Jews as to pagans. Second, John declared that ritual observance and cultic sacrifice were no guarantee against the final judgment. God’s fire burned through such externals; it demanded metanoia, “repentance” in the sense of a complete change in the way one lived. On both scores–hope for apocalyptic triumph and confidence in the Law–John cut the ground from under his own people.

What he did, in turn, was to deepen the crisis within Judaism. Instead of spinning out hopes for salvation in a new age, he pressed home the immediacy of God’s judgment and the individual’s responsibility to undergo conversion. And instead of encouraging the complacency of religious observance, he urged radical attention to the needs of one’s neighbor. By this dual focus on the existential and the ethical, John demystified both eschatology and the Law and radically reinterpreted their meaning. Eschatology, when stripped of apocalyptic myths about Yahweh’s defeat of the Gentiles, was about the personal immediacy of his judgment. And the Law, when freed from petty casuistry, was about being just in God’s eyes by exercising concern for one’s fellow man.

John’s call to personal responsibility captured the religious core of eschatology by freeing Yahweh from the role of cosmic avenger of Israel and making him the Lord of those who repent. Likewise his insistence on inner conversion recovered the heart of the Law by liberating it from narrow and burdensome legalism. John’s message, in short, reasserted the living kernel of Jewish faith–doing God’s will by being just and merciful–and freed it from the elaborate but dead husks in which it was trapped.

55

And Jesus followed in John’s footsteps. It is probable that when he left John’s inner circle, Jesus stayed in the south of Palestine for a period of time and continued to preach and baptize in imitation of his mentor. After his baptism beyond the Jordan, the Fourth Gospel says, “Jesus and his disciples went into the land of Judea; there he remained with them and baptized” (3:22). For a while, then, it seems there were at least two prophetic baptizers in the area.

But there was a different tone to Jesus’ message, and in the Fourth Gospel we read that “Jesus was making and baptizing more disciples than John” (4:1). Nonetheless, the preaching of Jesus, whatever its difference from John’s, continued some of the major themes of the Baptist: the reduction of apocalypse to its existential core, the condemnation of those who locked man’s relation to God inside the narrow confines of the Law, and the call for justice and charity as the enactment of fidelity to God. In fact, Jesus began to catch the attention of the ever-wary Pharisees, who had already disapproved of John’s antiestablishment preaching. Prudently Jesus decided, as the Gospel says, to leave for his native Galilee. Most likely only after the Baptist’s death did Jesus begin his own (and very brief) mission independent of John’s.

Being a prophet in those days was dangerous business, and both John and Jesus were soon to pay the price. Besides the disapproving Pharisees and Sadducees, there were two political powers in the country, both within a few miles of the Jordan, who watched the movements of these eschatological eccentrics with considerable disapproval.

In the south, at Jerusalem, was the notoriously stern and arrogant Roman prefect Pontius Pilate, who had arrived in Palestine in the Roman year 779(26 C.E.), just before John began his mission. Today he would probably, and correctly, be called an anti-Semite. His main jobs were to collect taxes and keep the public order as he put in his time in the provinces, awaiting a better assignment; but from the moment he arrived in the country he seemed never to miss a chance to offend pious Jews and in more than one instance to threaten and even murder them. Apocalyptic preachers, especially if they developed messianic delusions, were a threat to the empire and were better silenced. Jesus had no such pretensions, but when he met Pilate two years later, that would make no difference.

Pilate governed most of Palestine as a Roman province, but from the northern town of Tiberias on Lake Galilee Herod Antipas, a petty

56

Hasmonean prince and Roman vassal, controlled much of what was left, including Galilee and the trans-Jordan area where John often preached. Within a short while–either because he feared John’s large following or because he was insulted by the prophet’s criticism of his messy divorce and remarriage–Herod would have the Baptist imprisoned in the fortress of Machaerus east of the Dead Sea and soon thereafter murdered.

Luke’s Gospel (23:1-25) says that when Jesus went on trial at the end of his brief career, both these rulers had the occasion to ask him who he was and where he dwelled. Like the two disciples who met Jesus late one afternoon at the Jordan, Pilate and Herod also got no answers, not even an invitation to “come and see.” Herod laughed at him. The other one had him killed.[27]

57

3. The Kingdom of God

After John was imprisoned, Jesus came north to the towns around Lake Galilee to start his own mission, and his message exploded on the scene with a sense of overwhelming urgency: The eschatological future had already begun!

The time is fulfilled,

God’s reign is at hand!

Change your ways! (Mark 1:15)

Jesus’ preaching was as riveting as John’s, but different in tone and substance. Whereas John had emphasized the woes of impending judgment, Jesus preached the joy of God’s immediate and liberating presence. A dirge had given way to a lyric.

The contrasting life-styles of the two prophets betrayed their very different messages, and the difference was not lost on the people. John scratched in the desert for locusts in order to remind his followers how bad things were and how few would be saved. But Jesus rarely passed up a good meal and a flask of wine, regardless of the company, as if

58

to say that the eschatological banquet was now being served and everyone, including sinners, was invited. His reputation began to suffer because, in spreading the good news to all, he kept company even with prostitutes and tax collectors (Mark 2:16). No doubt some wags enjoyed playing one prophet off against the other–the lyrical Jesus against the railing Baptist–so as not to have to listen to either one. Jesus shot back at them:

To what shall I compare this generation? It is like children sitting in the market places and calling to their playmates [and mimicking the two prophets],

__ “When we piped, you wouldn’t dance,__ When we wailed, you wouldn’t mourn.”

For John came neither eating nor drinking, and they say, “He’s possessed.” I came eating and drinking, and they say, “Behold, a glutton and a drunkard, a friend of tax collectors and sinners.” But wisdom is justified by her deeds. (Matthew 11:16-19)

Yet the generation was right about one thing: From John to Jesus the tune had indeed changed, in fact as much as it had changed earlier from the Jerusalem of the Pharisees and Sadducees to the Jordan of John the Baptist. In all three cases–the orthodoxy of the Jerusalem establishment, the Protestantism of the Judean desert, and the Good News preached in Galilee–it was a question of invitation and response, of what was promised and what was demanded. The choices were clear. The reigning orthodoxy held out the promise of a future apocalyptic triumph in return for strict observance of the Law: the hard bread of obedience in this life, but an eschatological victory in the near future. The Baptist, on the other hand, preached a threatening judge who offered to save those who repented and changed: some existential anguish at first, but then the conviction that one was justified in God’s sight. But Jesus proclaimed a loving Father who was already arriving among his people, bringing peace and freedom and joy. One simply had to let him in, for the kingdom of God had begun.

When we ask what Jesus’ message offered and what it demanded–the invitation and the response–we find that Jesus took two important steps beyond his mentor. First, with regard to the offer, John the

59

Baptist had “existentialized” eschatology: He had demythologized the future apocalyptic catastrophe and proclaimed it to be God’s present judgment on the individual. Jesus, however, went a step further and “personalized” John’s existential eschatology: He interpreted it not as the harsh judgment of a terrifying God but as the intimate presence of a loving Father. Second, with regard to the demand, John had delegalized the Law by making it a matter of sincere piety and justice. But Jesus went further and relativized the Law by referring it to God as its beneficent author and to men and women as its immediate object.

To put it succinctly, in Jesus’ message the offer was the presence of the Father, and the required response was mercy toward one’s neighbor. These phrases may sound like tired slogans, and perhaps they are. But they contain the revolution that Jesus unleashed within Judaism: a radically personal eschatology that was fulfilled in a new interpersonal ethic.[28]

INVITATION: THE FATHER’S PRESENCE

The heart of Jesus’ message is summarized in the strikingly simple name with which he addressed the divine: “Abba,” the Aramaic word for “papa” (Mark 14:36). This familial usage, which underlies all Jesus’ references to “the Father,” was a shock to the then current idea of God.[29] Late Judaism tended to see Yahweh as a distant and almost impersonal Sovereign whose presence to mankind required the mediation of angels, the Law, and the complexities of religious ritual. But with the simple and intimate word “Abba,” Jesus signaled that God was immediately and intimately present, not as a harsh judge but as a loving and generous father. His presence was a pure and unearned gift, and one could relate to him without fear. “Be not afraid,” Jesus told his followers. “Do not be anxious about your life,” “Do not worry.”

Look at the birds of the air: they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not of more value than they? (Matthew 6:25-30)

60

Nor did one have to earn this Father’s favor or bargain for his grace by scrupulously observing the minutiae of the Law. One simply had to call on him.

Ask and it will be given to you. … What man of you, if his son asks him for bread, will give him a stone? Or if he asks for a fish, will give him a serpent? If you, evil as you are, know how to give good things to your children, how much more will your Father who is in heaven give good things to those who ask him. (Matthew 7:7, 9-11)

When you pray, say “Abba … ” (Luke 11:2)

This immediate presence of God as a loving Father is what Jesus meant by the “kingdom.”[30] The notion of the kingdom of God (or in Matthew’s Gospel, the kingdom “of heaven”) simply spells out Jesus’ experience of the Father’s loving presence that is captured in the word “Abba.” As Jesus preached it, the kingdom of God had nothing to do with the fanciful geopolitics of the apocalyptists and messianists–a kingdom up above or up ahead–or with the juridical, hierarchical Church that Roman Catholics used to find in the phrase. Nor did the term primarily connote territory, spiritual or otherwise. Rather, it meant God’s act of reigning, and this meant–here lay the revolutionary force of Jesus’ message–that God, as God, had identified himself without remainder with his people. The reign of God meant the incarnation of God.[31]

This entirely human orientation of the Father–the loving, incarnate presence of a heretofore distant Sovereign–marked the radical newness of Jesus’ message of God’s reign. The kingdom was not something separate from God, like a spiritual welfare state that a benign heavenly monarch might set up for his faithful subjects. Nor was it any form of religion. The kingdom of God was the Father himself given over to his people. It was a new order of things in which God threw in his lot irrevocably with human beings and chose relatedness to them as the only definition of himself. From now on, God was one with mankind.

This utterly new doctrine is what gave revolutionary power to the “Beatitudes” that Jesus preached.[32] The kingdom he proclaimed–

61

God’s presence among men and women–meant that from now on God’s exercise of power was entirely on behalf of mankind, and especially the poor and needy. God’s incarnation among them had already begun and would soon come to its fullness:

Blessed are you poor,

__ for yours is the Kingdom of God.

Blessed are you who hunger,

__ for you shall be satisfied.

Blessed are you who weep,

__ for you shall laugh. (Luke 6:20-21)

The radicalness of Jesus’ message consisted in its implied proclamation of the end of religion, taken as the bond between two separate and incommensurate entities called “God” and “man.” That is, Jesus destroyed the notion of “God-in-himself” and put in its place the experience of “God-with-mankind.” Henceforth, according to the prophet from Galilee, the Father was not to be found in a distant heaven but was entirely identified with the cause of men and women. Jesus’ doctrine of the kingdom meant that God had become incarnate: He had poured himself out, had disappeared into mankind and could be found nowhere else but there. This incarnation was not a Hegelian “fall” of the divine into history, or Feuerbach’s simplistic reduction of God to the human project of self-fulfillment. But neither did it mean the hypostatic union of two natures, the divine and the human, in a God-man called Jesus of Nazareth. The doctrine of the kingdom meant that henceforth and forever God was present only in and as one’s neighbor. Jesus dissolved the fanciful speculations of apocalyptic eschatology into the call to justice and charity.

Jesus’ message of the kingdom radically redefined the traditional notions of grace and salvation and made them mean nothing other than this event of God-with-man. Salvation was no longer to be understood as the forgiving of a debt or as the reward for being good. Nor was it a supernatural supplement added on to what human beings are, some kind of ontological elevation to a higher state. All such metaphysical doctrines are forms of religion, which Jesus brought to an end. His proclamation marked the death of religion and religion’s God and

62

heralded the beginning of the postreligious experience: the abdication of “God” in favor of his hidden presence among human beings. The Book of Revelation, written toward the end of the first century of Christianity, captured this idea dramatically and concretely, albeit apocalyptically, in a vision of the end of time.

Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more. And I saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a great voice from the throne saying:

“Behold, the dwelling of God is with men and women. He will dwell with them, and they shall be his people, and God himself will be with them. He will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more, for the former things have passed away.” (21:1-4)

RESPONSE: AN ETHICS OF MERCY

The morality Jesus prescribed followed from the kingdom he proclaimed. Unlike Greek philosophy, Jesus’ ethical teachings were not based on a metaphysical concept of human nature and were not ordered to a eudaemonic theory of self-fulfillment. The moral ideal of classical Greek culture had been captured in Pindar’s poetic phrase Genoi’ hoios essi, “Become what you already are” (Pythian Odes, 11, 72).[33] Ethics was the extension of ontology. The Greeks saw the good as a form of being, and they derived the ethical “ought” from the ontological “is,” from the ineluctable structures of human nature. The moral person, therefore, was one who followed the finality of his or her essence, both spiritual and physical, instead of doing violence to it. In this view morality was grounded in free choice, but in the sense of an intelligent decision to obey the inner dictates of one’s being. Insofar as it was rooted in ontology, Greek ethics was ultimately a matter of consciously conforming to an overriding necessity, and Pindar’s protreptic to realize one’s nature ended up as Nietzsche’s counsel to love one’s fate: amor fati.

63

In Jesus’ message, however, ethics was not a matter of pursuing the fulfillment of one’s nature within a framework of inevitability. Nor, as in the religious orthodoxy of the time, did it mean scrupulously obeying a Law imposed from without. Rather, it was a free response to a complete surprise: the unearned gift of God himself, who had suddenly arrived in one’s midst. Here ethics was not an extension of ontology, not the exfoliation and realization of what is already, if inchoately, the case. Rather, it meant metanoia, conversion, or repentance: completely changing one’s orientation and starting over afresh in response to something entirely new. “The kingdom of God is at hand. Metanoiete: Change your ways” (Mark 1:15).[34]

Moreover, God’s presence in and as his people could not happen apart from this conversion: no metanoia, no kingdom. Although the kingdom was entirely God’s gift and grounded in his initiative, the offer of God’s presence turned into the challenge to let it happen; the invitation to the kingdom became the demand to live the dawning future–God’s reign–in the present moment. Living the future in the present meant doing “violence” to the kingdom (Luke 16:16), not, however, by storming its walls with one’s virtues or bribing one’s way in with religious observance. The “violence” of living the future in the present was metanoia, “repentance.” That did not mean self-flagellation for one’s sins but “turning oneself around” and wholly changing one’s life into an act of justice and mercy toward others. In Jesus’ message, the invitation and the response were interdependent. The promised presence of God was the meaning of the demand for justice and charity, and yet only in such acts of mercy did the eschatological future become present.

This mutuality–eschatology as the ground of ethics, and ethics as the realization of eschatology–is what made Jesus’ moral demands so radical. Those who accepted God’s kingdom by doing God’s will in the world already had as a gift what pious believers tried to earn through observance of the Law. Charity fulfills the Law–not because it makes God become present, but because it is his presence. And when God arrives on the scene, Jesus seemed to say, all go-betweens, including religion itself, are shattered. Who needs them? The Father is here!

In the concrete, this meant relativizing the Mosaic Law. Jesus, of course, was a pious Jew and therefore was far from intending to

64

abrogate the Law, which he too saw as an expression of God’s abundant love for his people.[35] But he was also a pious Jewish prophet, and specifically one who was convinced that the eschatological line separating the present from the future was already being crossed: History was entering its promised denouement. The eschatological nearness of the Father seared through all mediations and established a radically new order that demanded an equally radical response. Thus Jesus attacked not so much the specific rules of the Law as the legalistic attitude that blinded people to the fact that the Law, like its divine author, was entirely at the service of mankind. For example, when the Pharisees criticized Jesus’ disciples for violating the Sabbath by plucking and eating ears of corn as they walked through a field, the prophet retorted: “The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath” (Mark 2:27). The Law, in short, was a gift from God, not a burden, and it should be bent in man’s favor and even overridden when the need arose.[36]

Jesus did not engage directly in the then current dispute about whether the Law should be reduced to the simple Ten Commandments (the viewpoint of the Hellenistic Jews of the Diaspora) or should comprise the entire Torah and the commentaries of the scribes (as Palestinian Jewry generally held). Rather, with the authority of a prophet he cut through the theological complexities of that debate and pointed to the heart of what Judaism was about: revering God by loving one’s neighbor.[37]

If the Father was henceforth identified with human beings–that is, if the kingdom of God was at hand–then strictly speaking there was no longer a God-up-above upon whom one could make religious claims by scrupulously observing the Law. In that sense, the demands of mercy that Jesus made were more rigorous than the stipulations of the Law. In calling for the commitment of the whole person to the immediate presence of the Father, Jesus necessarily pointed that commitment in the direction of one’s fellow human beings, especially the socially powerless and disenfranchized. The ethics of the kingdom entailed always taking the side of the weaker or disadvantaged party and therefore the side of the poor and oppressed–including those whom the religious establishment declared to be outcasts. When the Pharisees criticized him for eating with such sinners, Jesus, citing God’s words to the prophet Hosea, responded with a maxim that summed

65

up not only the Jewish Law but his own eschatological ethics as well: “Go and learn what this means: ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice'” (Matthew 9:13).[38]

TIMING: THE PRESENT-FUTURE

If we ask about the timing of this eschatological event, that is, when God’s kingdom was supposed to arrive, we are faced with an apparent contradiction. According to what Jesus preached, the reign-of-God-with-man at one and the same time had already arrived in the present and yet was still to come in the future. This paradox of the simultaneous presence and futurity of God’s kingdom brings us to the core of Jesus’ message: the eschatological present-future.[39]

On the one hand, it seems to be the case that Jesus, in conformity with the eschatological spirit of the times, did indeed preach that the kingdom lay in the immediate future but had not yet arrived. For example, he taught his disciples to pray: “Abba, may thy kingdom come!” But on the other hand, even if Jesus did expect an imminent and dramatic arrival of God among his people, he made no attempt to calculate the time of that coming, either in chronological or in apocalyptic terms. He refused to engage in predictions about its arrival, he never preached the dualism of “the age of darkness” followed by “the age to come,” and he may not even have believed in a catastrophic end of the world. It seems that for Jesus the coming of God’s kingdom was not measurable in such linear terms as “before” and “after,” whether those be chronological or apocalyptic. Strictly speaking, it appears that for Jesus the future did not lie up ahead.

The uniqueness of Jesus’ message lay in his conviction that in some way the future kingdom had already dawned and that the celebration could begin. The Baptist before him had Preached an impending final judgment, but Jesus went him twice better: not judgment but a gift, in fact the gift of God himself, and not just impending but right here and now. God had already started to reign among men and women.

The kingdom of God has come upon you. … Blessed are the eyes which see what you see. For I tell you that many prophets and kings

66

desired to see what you see, and did not see it, and to hear what you hear and did not hear it. (Luke 11:20, 10:23-24)

This paradoxical timing of the kingdom–the fact that it is both already present and yet still to come–tells us something essential about Jesus’ vision of history. For him the past (mankind’s sinful distance from God) was over, and the future (God’s gracious identification with his people) had already begun. For Jesus, “past” and “future” were not points on a chronological or apocalyptic time-line: a bygone “no longer” and an upcoming “not yet.” Rather, they were eschatological categories that had to be read in terms of the only thing that mattered to Jesus: the presence of God-with-man. The “past” was the reign of sin and Satan, the alienation of people from God, the weight of all that was impenetrable to the Father’s gift of himself. And for Jesus all of that was gone or going. In its place came the “future,” the presence of the Father himself among those who lived lives of justice and mercy. This unique, nonchronological sense of time explains why Jesus’ message was so short on apocalyptic imagery. No such futuristic imagery was needed, for the eschatological line between the age of sin and the age of grace was already being crossed. God was now with his people.

The name Jesus used for this passing of the ages was “forgiveness”–but not in the usual religious sense of that term. The Father’s forgiveness was not the canceling of an ontological debt, the undoing of some mythical sin that Adam had allegedly passed down through the generations. Nor was it God’s benign overlooking of one’s personal transgressions, an absolution for bad deeds done and good ones left undone. Forgiveness, as Jesus preached it, referred not primarily to sin at all but to the crossing of the eschatological line. What was “given” in the Father’s for-giveness was the eschatological future–that is, God himself. Thus, forgiveness meant the arrival of God in the present, his superabundant gift of himself to his people, his self-communicating incarnation.

The Father’s forgiveness meant a new beginning in the history of the ages, and for those who accepted his gift, the eschaton no longer lay up ahead but had arrived in the present. God was here in a new form of time, the existential present-future. Therefore, to believe in the arrival of God’s kingdom and to be forgiven meant the same thing–

67

to be a prolepsis of God, to live the future now. It meant directing one’s hopes toward the “future eschaton,” that is, toward God himself, but then becoming in the present one’s desire for that future which had already begun. “Set your hearts on the kingdom,” Jesus said. “Store up treasures there, for where your treasure is, there is your heart” (cf. Matthew 6:33, 20f.).

In Jesus’ preaching, the happening of this forgiveness, the coming of the kingdom, was entirely the initiative of God. And yet at the same time it was not an objective event that dropped out of the sky. God became present when people allowed that presence by actualizing it in lives of justice and charity. The promise of eschatology was converted into the demand for love and justice. “Be merciful, even as your Father is merciful” (Luke 6:36). Jesus extended this invitation to all who would hear it: “Convert, repent,” that is, “Change the way you live, by accepting God’s forgiveness.” And accepting forgiveness meant enacting justice and mercy in the world, for the gift of God-with-men was a future that became present only in such a life of conversion.

And like a good rabbi, Jesus set the example. His followers had once asked him, “Master, where do you dwell?” and the answer was that Jesus dwelt beyond himself. He was an eschatologist in the literal sense of the term: an extremist. His own family thought he was “outside himself,” the scribes thought he was “possessed,” and others declared him “mad” (Mark 3:21-22, John 8:48). All of them were right: Jesus certainly was possessed, not, however, by Beelzebub, as the scribes thought, but by something that religious officialdom all too seldom understands: God’s uncontrollable present-future, which Jesus felt had swept him up beyond himself. Jesus was what he was for, the presence of God among men. He lived his eschatological cathexis so intensely that he lost his identity to that present-future and became nothing but his hope for its realization. The kingdom was his madness. He celebrated it with anyone who would join him at table, declared everyone free in its name, broke all rules that stood in its way, and finally gave up his life for it–or rather, gave up his life to save the only thing he lived for.

Where did Jesus dwell? When he said he had nowhere to lay his head (Matthew 8:20), he was not referring simply to the obvious fact that he was an itinerant preacher. He was declaring that he lived

68

beyond himself. He was giving his address as the presence of God among men. He claimed no family, no mother or brothers or sisters except those who lived with him there in God’s present-future (12:48-50). He was no part-time prophet. The kingdom was his life, and “What would a man give in exchange for his life?” (17:26). The kingdom was like a pearl of immense value that Jesus had found and that he sold everything to buy (13:46).

This was the same call he held out to his followers: If you wish to be perfect, go and sell what you own and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me” (Matthew 19:21).The vocation of Jesus and his followers was to live God’s dawning presence–not up above in heaven or up ahead in an apocalyptic future, but there in their midst, at the edge of things where security unravels into risk, at the center of things where common sense is challenged by the wager that henceforth God is found only among men and women.

The presence of God among men which Jesus preached was not something new, not a gift that God had saved up for the end of time. Jesus merely proclaimed what had always been the case. He invited people to awaken to what God had already done from the very beginning of time. The eschaton that Jesus proclaimed was not a new coming of God but a realization on man’s part that ever since the creation God had been there among his people. The “arrival” of the present-future was not God’s return to the world after a long absence but the believer’s reawakening to the fact that God had always and only been there.[40]

All Jesus did was bring to light in a fresh way what had always been the case but what had been forgotten or obscured by religion. His role was simply to end religion–that temporary governess who had turned into a tyrant–and restore the sense of the immediacy of God. Jesus, the first disciple of the kingdom of God, was “like a householder who brings out from his storeroom things both new and old” (Matthew 13:52) . The newness of his message was the shock of something old and forgotten that was found again. Like the psalmist, Jesus could say:

I will open my mouth in parables,

__ I will utter dark sayings from of old,

69

Things that we have heard and known,

__ That our fathers have told us.

We will not hide them from their children,

__ but will tell them to the coming generation. (Psalm 78:2-4)

The “dark sayings from of old,” the “things hidden since the foundation of the world” (Matthew 13:35),were the content of Jesus’ message: The Father of the kingdom was the very same Father of the creation who had made all things good, had made man and woman good, who “saw everything that he had made, and it was very good” (Genesis 1:31).

To receive God’s eschatological forgiveness was to realize that everything was already in God’s graceful presence and that everyone was already saved–precisely because they did not need salvation: They had already been saved from the beginning. Jesus’ proclamation of eschatological forgiveness was simply a reminder that everything had already been done, that grace (which means God) had already long since been abundantly bestowed, and that the only task left to do now was to live out that gift. Jesus’ job as a prophet was to put himself out of business.

70

4. God’s Word at Work

Jesus did not define the kingdom of God so much as he enacted it by the way he lived. In the previous section we considered the content of his message: The future becomes present, the Father becomes incarnate, wherever mercy and justice are done. We now take another look at that same message, but this time in terms of how it was inscribed in Jesus’ style of living and preaching. We shall consider the manner in which Jesus concretely enacted the kingdom in the table fellowship that he shared with his followers, in the parables that he told them, and in the “signs and wonders” (Acts 2:22) that he worked among the people.

When we search the Gospels for clues to how Jesus lived, we get the impression that, in the scarce two years of his mission, he spent an inordinate amount of time at the dinner table and not always in the best of company. Jesus admitted as much: “I came eating and drinking,” he said (Matthew 11:19). And on these occasions, in turn, he frequently preached about the kingdom of God in terms of a great meal, as if to say that the eschatological presence of the Father was like a banquet,

71

as generous as the one at which he and his outcast friends reclined, with invitations showered on those who seemed the least deserving.

The kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king who gave a marriage feast for his son, and sent his servants to call those who were invited to the marriage feast; but they would not come. … Then he said to his servants, “The wedding is ready, but those invited were not worthy. Go therefore to the thoroughfares, and invite to the marriage feast as many as you find.” (Matthew 22:2-3, 8-9)

The meals of fellowship that Jesus shared with his followers were an enactment of the reign of God, a sacrament of the Father’s incarnate presence. They were not just a model of, but, more important, an anticipatory realization of, the dawning presence of God–the first course, we might say, in the eschatological banquet. And on the invitations to these dinners was printed “Whores and tax collectors first! ” (cf. Matthew 21:31). Jesus’ meals were typified by their inclusion of such pariahs and by the prophet’s proclamation that the Father’s gift in these end-times was universal forgiveness.

When a prostitute, on her off hours, joined Jesus at table at a Pharisee’s house and even washed his feet, Jesus told his shocked host, “Her sins, which are many, are forgiven, for she loved much; but he who is forgiven little, loves little” (Luke 7:47). And when the pillars of the religious establishment questioned his practice of eating with the hated tax collectors–an act that violated the Law–Jesus responded, “Those who are in good health have no need of a physician, but rather those who are sick; I came to call not the righteous, but sinners” (Mark 2:17).