Old Testament Life and Literature (1968)

Gerald A. Larue

Chapter 10 – Saul

THE Deuteronomic history of Israel continues with the stories of Samuel and Saul which form the records of the beginnings of Hebrew kingship. Some sources are designated, such as "The Book of the Acts of Solomon" (I Kings 11:41), "The Chronicles of the Kings of Israel" (I Kings 14:19, 15:31, 16:5) and "The Chronicles of the Kings of Judah" (I Kings 14:29, 15:7, 22:45), but multiple traditions may be discerned in contradictions and doublets. There are three separate descriptions of the origin of the monarchy, two favorably disposed toward kingship and the third hostile (compare I Sam. 7-8, 9-10, 11). Saul’s death is reported twice (I Sam. 31, II Sam. 1), and there are other indications of composite authorship.1 Some scholars attempt to analyze sources according to Pentateuchal patterns, developing a documentary hypothesis. A simpler and sounder solution is recognition of the principle of progressive interpretation by which the earliest source in Samuel was expanded by those who, without altering the words of the earlier tradition, added other points of view and new interpretive material, thus altering the major thrust of the earlier writing. The final stage in this process is the editing by Deuteronomists.

The earliest source in I Samuel begins in Chapter 4 with the account of the continuing struggle between powerful Philistine city-states and Hebrew communities. There seems to be little reason to question the historicity of this information. Indeed, as the early source is read, the impression grows that an objective witness, someone personally familiar with events described, produced the record. Once the Hebrew kingdom came into being, royal records, from which some of the material may have been drawn, would be made. The early source in Samuel is one of the best and earliest examples of accurate historical writing known to us, and it forms the core of what was to become the record of the Hebrew kings.

Read I Sam. 1-3

The first three chapters of Samuel are late additions explaining how the extraordinary role that the prophet Samuel played in Hebrew history could be traced to his miraculous birth, the consecration of his life to Yahweh’s service, and to the divine summons and commission.

|

CHART IX

|

||||

| Years B.C. | Archaeo- logical Period | Palestine | Egypt | Mesopotamia |

| Last quarter twelfth century to middle of ninth century | Iron Age | Time of Samuel the seer-prophet. Philistines battle the Hebrews. the battle of Aphek, the loss of the Ark and the return of the Ark, the destruction of Shiloh. The Ammonites attack and are beaten by Saul. Saul is crowned king, the beginning of the kingdom. David enters Saul’s court, Saul battles Philistines, David becomes an outlaw, Saul and Jonathan are killed. Ishba’al becomes king in Israel. David becomes king in Judah. David unites Israel and Judah. David conquers Jerusalem. David brings the Ark to Jerusalem. David extends the boundaries of the kingdom. Absalom revolts and is killed, Adonijah revolts and is killed Solomon becomes co-regent until David’s death. Solomon builds the temple and palace, Jeroboam revolts and is exiled, The saga of the nation, the Davidic history and law codes are written down Solomon dies. Jeroboam returns from exile. The kingdom splits in two. |

Egypt is too weak from the war with the Sea People and the loss of Palestine to exercise much authority.

Egypt begins to grow in strength |

Assyrian expansion begins under Tiglath Pileser I (ca. 1116-1078); campaigns in Anatolia and Phoenicia. Later, Assyrian power declines; Phoenicia begins to expand by sea. |

The psalm or prayer of Hannah in Chapter 2 is, in reality, a royal psalm composed to honor the king and may be as late as the post-Exilic era (note references to the messianic king in Verse 10) and, apart from Verse 5, has little to do with joy in the birth of a child. Later this song was to serve as a prototype for the Magnificat (Luke 1:46-55). Interesting worship customs are reflected in the opening chapters: the father performs the ritual on behalf of the family (I Sam. 1:4, 21) and the priest appears to be little more than the keeper of the shrine, receiving payment by sharing in the offerings (I Sam. 2:13 ff.). The vocational summons that came to Samuel from Yahweh occurred in the temple during sleeping hours, suggesting a rite of incubation.2

Read I Sam. 4-7:2

The earliest account begins with the report of the battle of Aphek, a strategically located Hebrew city at the edge of Philistine territory that had been captured by Joshua (cf. Josh. 12:18). Ebenezer, the locale of the Hebrew encampment, has not been discovered. The Hebrews, defeated in the first skirmish, sent to Shiloh for the sacred ark3 of Yahweh Saba’oth ("Yahweh militant" or "Yahweh of hosts"). The presence of this sacred emblem brought a moment of panic to the Philistines and a surge of confidence to the Hebrews.4 Despite the presence of the ark, the Hebrews were defeated and the ark captured and placed as a trophy of war in the temple of Dagon at Ashdod.5 A plague attributed to the ark encouraged the Philistines to return it to the Hebrews and it was sent to Beth Shemesh and deposited in a field belonging to Joshua of Beth Shemesh. The Hebrews made no attempt to move it into the city; instead they sacrificed before it in the field. A later writer explained that the Levitical priests attended the ark in the field (6:15).6 The death of seventy men (possibly from the plague) was explained on the basis of the holiness of the ark, for holiness could benefit or injure. Ultimately, the ark was sent to Kireath-Jearim, and remained in the possession of a certain Abinadab until David removed it to Jerusalem. The Old Testament does not explain why the ark was not returned to Shiloh, but archaeological excavation of Shiloh has revealed that the city was destroyed about this time, and it has been suggested that perhaps the Philistines, continuing their forays, had sacked it.

Suddenly the ark stories cease and a cycle of traditions pertaining to the kingship begins. The amount of reliable data in the ark traditions has been questioned, but they constitute all of the literature that we possess describing a period that has received but meagre assistance from archaeological studies so far.

Read I Sam. 11:1-11, 15

It has been noted that three different accounts tell of Saul’s assumption of the kingship. The one best fitting the cultural context and presumed to be earliest is in Chapter 11:1-11, 15, recording the siege of Jabesh-Gilead in Transjordan by the Ammonites under Nahash. Unable to cope with the powerful enemy and hopeful of preventing destruction of the city, the Jabesh-Gileadites offered to surrender themselves and enter into a covenant of slavery (11:1). Nahash agreed, demanding that, as a symbol of servitude, the right eyes of the inhabitants be gouged out. In the period of grace before the sealing of this humiliating and painful contract the story reached Saul and, in violent anger experienced under divine seizure (thus designating his charismatic role), Saul summoned the tribes on the threat of violent retaliation and delivered the beleaguered city. Saul’s military prowess led to his coronation at the Yahweh shrine of Gilgal.

Read I Sam. 9-10:16

A different tradition describes Samuel’s selection of Saul. Searching for lost asses, Saul consulted Samuel, who is described as a seer or clairvoyant. Having been informed by Yahweh that Saul was the divine choice for savior of the people, Samuel anointed God’s man in a private ceremony.7 After leaving Samuel, Saul met a band of ecstatic prophets and experienced divine seizure, demonstrating, thereby, charisma. Saul’s selection is part of a divine plan. This tradition, generally believed to be later than the one discussed previously, may contain a solid historical core in the report of Saul’s seizures. The description of the ecstatic prophets of Gibeath-elohim is probably accurate and contributes to the study of early Hebrew prophecy. Perhaps this story comes from a prophetic circle desirous of emphasizing the role played by one of their profession in the selection and anointing of the king.

Read I Sam. 8; 10:17-24; 12:1-5

Another account expressing a completely different point of view states that, in their desire to be like other nations, the people demanded a king. Samuel’s speech, reflecting an era familiar with the harshness of monarchic despotism under Solomon and his successors, warns of the dangers. Selection was by sacred lot, and Saul, hiding in the baggage, was chosen. Here, the writer’s attitude is that acceptance of a human ruler was tantamount to rejecting Yahweh as king (8:7). Those preserving this tradition believed in a theocratic state and looked back to the old independent tribal structure (idealized in their thinking) as the time when reliance upon divine leadership was customary. The way of kingship was the way of Canaan.

Read I Sam. 7:5-17; 10:25-27; 11:12-14

Several small units of traditions were added. Chapter 7:5-17 is an etymological legend explaining how Ebenezer got its name. Chapters 10:25-27 and 11:12-14 record how resistance to Saul’s leadership was quashed when he won the battle of Jabesh-Gilead. An interesting reference to the use of shrines as repositories for records (10:25) may point to the sources of the sanctuary legends utilized by Bible editors.

Read I Sam. 13-14

Saul’s story which began in Chapter 11 is picked up again in Chapter 13. How much has been lost from the early account can be seen by the sudden introduction of Saul’s son, Jonathan, as a young warrior (13:2). No traditions of Saul’s marriage and home life remain, and even the details of his age and length of reign have been lost (13:1). The Philistine struggle continued, interrupted by a note designed to prepare the reader for the fall of the house of Saul (13:7b-15a; cf. 10:8). Once Saul and Jonathan had only 600 men under their command, but a later editor heightened the odds, listing Philistine forces as 30,000 chariots and 6,000 horsemen (13:5), unlikely numbers for the hill country of Michmash, and dramatized the inequality of arms, suggesting that within the entire Hebrew army only Jonathan and Saul possessed weapons of war (13:22)!

When an earthquake put the Philistine camp in an uproar (14:15), Saul sought an oracle from the sacred ark8 but received no answer. To ensure divine support for an attack, Saul vowed that none of his men would eat that day until the Philistines were routed. Unwittingly Jonathan violated the oath (14:27).

In the evening Saul’s exhausted and hungry men began to kill sheep and cattle. Killing for food had ritual significance. The blood, which in Hebrew thought was believed to contain the life power, had to be poured out, signifying its return to the deity. Hungry Hebrew soldiers ignored this ritual. A huge stone was rolled into place and animals were slain at this spot, presumably with the blood being poured on or beside the rock (14:33 f.). The text says "Saul built an altar, to Yahweh." Whether or not the stone itself served as the altar, or whether Saul built a separate altar for burnt offerings, cannot be determined. The writer of this account, unlike the writer in 13:8 and following verses, finds nothing objectionable in what might be termed Saul’s priestly role.

When Saul again sought an oracle from Yahweh, and again received no response, he surmised that the deity had been offended and vowed that the guilty party would die. Again, the concept of corporate personality is demonstrated: the actions of one individual affected the well-being of the entire group. Sacred lots, named, according to a tradition preserved in the LXX, "Urim" and "Thummin" were consulted. What techniques were used are not known, but Jonathan was identified as the offender (14:42). Saul’s vow to kill the guilty party was not fulfilled, for the troops voted against the killing of the popular prince. What is implied in the note that Jonathan was "ransomed" is not clear and perhaps someone died in his place. Deuteronomic editors close this portion of Saul’s story with a summary of his activities and a few words about his family.

Read I Sam. 15-16:13

The next cycle of stories describes the decline of Saul’s power and the rise of the Davidic line. The account of Saul’s failure to destroy everything and everybody in the Amalakite war, thereby offending Yahweh (ch. 15), makes the transition from the previous material. The story of the divine choice and secret anointing of David (16:1-13) is late.9

Read I Sam. 16:14-25:44

The earliest tradition of David’s coming to Saul’s court begins in I Sam. 16:14-23. A mental illness, diagnosed as an evil spirit sent by God, troubled Saul. Music soothed him, and David, a skilled musician, was brought to play the lyre. As a member of the royal household, David won Saul’s affection (16:21), became a bosom friend of Jonathan (18:3 ff.), and married Saul’s daughter Michal (18:20 ff.). Participating in the military forays against the Philistines, David excelled as a warrior and became, to the women of Israel, a popular hero and the subject of a chant:

"Saul has slain his thousands, But David his ten thousands."

– I Sam. 18:7

Such repute evoked jealous hostility from Saul who recognized in David a potential rival for the kingship. One tradition suggests that David’s marriage to Michal was sanctioned by Saul because the king saw a way to get rid of David by demanding a marriage price10 of 100 Philistine foreskins (18:25 ff.). A later editor explained that David presented 200 foreskins, not the required one hundred. Thwarted in his attempt to eliminate his rival, Saul sought to kill David on the night of the wedding but Michal’s clever ruse saved David’s life (19:11-17). David, with the band of guerrilla warriors, fled to the wilderness (23:6-15).

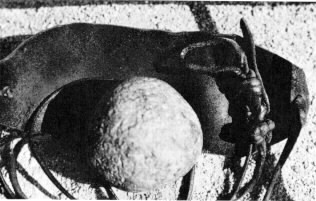

A SLINGSTONE AND SLING. The stone in the photograph is about the size of a tennis ball. The pouch and thongs are modern replicas patterned after slings shown in ancient inscriptions and drawings. The stone was placed in the pouch, and then, suspended by the two thongs which were held in one hand, was whirled rapidly about the head. When one thong was released the stone left the pouch and hurtled toward its target. For a reference to the accuracy of certain slingers see Judg. 20:16.

A SLINGSTONE AND SLING. The stone in the photograph is about the size of a tennis ball. The pouch and thongs are modern replicas patterned after slings shown in ancient inscriptions and drawings. The stone was placed in the pouch, and then, suspended by the two thongs which were held in one hand, was whirled rapidly about the head. When one thong was released the stone left the pouch and hurtled toward its target. For a reference to the accuracy of certain slingers see Judg. 20:16.

A later and completely different record of the development of David’s warrior reputation and early relations with Saul, preserved in Chapter 17, tells of the slaying of the Philistine giant, Goliath. But even here, two traditions are merged. In one David is described as leaving Saul’s court to do battle (17:1-12, 32-54) ; in the other David had not yet met Saul but brought provender for his brothers in Saul’s army. Troubled by Goliath’s taunts, David killed the giant with a stone from his sling.11 Only then was he introduced to Saul (17:12-30, 55-58; 18:1-2; 17:31 is a transitional verse). Another popular folk tale credits one of David’s soldiers, Elhanan, with killing Goliath (II Sam. 21:19), leading some scholars to speculate that perhaps the hero David usurped a title of "giant killer" rightfully belonging to another.

ASSYRIAN WARRIORS HURLING STONES. The soldiers carry extra ammunition in their left hands. The carving is from a wall decoration in the palace of Sennacherib at Nineveh (early seventh century).

ASSYRIAN WARRIORS HURLING STONES. The soldiers carry extra ammunition in their left hands. The carving is from a wall decoration in the palace of Sennacherib at Nineveh (early seventh century).

Traditions blackening Saul and enhancing David’s reputation expand the story of David’s marriage into Saul’s family (18:10-19) and the tradition of Jonathan’s affection for David (19:1-10; 20:1-42).12 The approval and protection of David by the prophets is recounted in 19:18-24. Saul’s reputation suffers further in the story of the flight of David’s parents to Moab (22:1-5). Even the expanded accounts of David’s wilderness adventures and his merciful action in saving Saul’s life13 magnify David’s heroic stature (23:15-24:22). The section closes with an editorial report of Samuel’s death (25:1).

The early tradition continues in Chapter 25 with the story of Nabal ("fool" – see 25:25). David, with his armed guerrillas, guaranteed protection from plunder if material support for himself and his men was promised (25:21). Nabal refused to pay and David prepared to raid his holdings. By taking goods to David’s camp, Nabal’s wife, Abigail, saved the situation (25:23 ff.). Abigail’s presentation speech has been expanded by later writers (verses 28-31 were probably additions). Upon learning of his wife’s action Nabal suffered a paralytic stroke and soon died; David married Abigail. Meanwhile, Saul gave Michal, David’s first wife, to another man, Palti. David acquired still another wife, Ahinoam (25:43 f.).

Saul continued his pursuit of David. At one point David could have killed the king, but fear of the taboo of killing Yahweh’s anointed prevented him (ch. 26). David’s speech to Saul on this occasion reflects the belief that Yahweh could only be worshiped within his own territory (26:19), indicating that religious belief of this period was monolatrous rather than monotheistic.14

Read I Sam. 27; 28:1-2; 29; 30

Convinced that Saul would not cease in the attempt to destroy him, David joined the Philistines. His adventures are recorded in Chapters 27; 28:1-2; 29; 30. His Philistine allies believed he raided Judaean towns (in reality he was plundering desert tribal groups) and gave him the city of Ziklag (location unknown). Meanwhile David courted the Hebrews, sharing booty with Judaean cities. A tense moment came when the Philistines prepared to attack the Hebrews at Mount Gilboa and included David in the forces. Fortunately, certain Philistine leaders distrusted him and insisted that he be sent back to Ziklag (ch. 29). Meanwhile Ziklag had been raided by the Amalakites and the inhabitants, including David’s two wives, had been led away as captives. David pursued and rescued his people (ch. 30).

The end of Saul’s leadership in the Hebrew kingdom was at hand and the tragic decline of the first monarch in Israel is movingly portrayed in his desperate search for supernatural guidance (ch. 28:3-25, where Samuel’s death is reported once again). Rejected by Yahweh, unable to receive an oracle through regular channels or communication with the deity (28:6), Saul turned to a necromancer – one who consorted with the dead. The prophet Samuel was raised (visible only to the medium) and Israel’s defeat and Saul’s death were foretold. The story, probably more interpretive than factual, indicates belief in the continued existence of the individual in Sheol, the place of the dead, but the nature of this existence is not clear.

The battle of Mount Gilboa is briefly reported (ch. 31). Saul’s sons were killed, and Saul, to prevent capture and torture, committed suicide. His decapitated body and the bodies of his sons were nailed to the wall of the city of Beth Shan as a final token of Philistine derision and defilement. Saul’s head was sent throughout the Philistine kingdom as a proof of the monarch’s death. The people of Jabesh-Gilead, remembering perhaps their earlier deliverance by Saul, rescued the bodies and provided proper burial for the members of the royal family. Thus Saul’s regal career ended as it had begun, with the people of Jabesh-Gilead.

Read II Sam. 1

A slightly different report of Saul’s death is put in the mouth of the Amalakite courier who informs David of the death and presents Saul’s crown and personal amulet as verification. David’s lament, which the editor notes is taken from the Book of the Upright (Jashar) – a work unfortunately lost to us – is generally conceded to be one of the oldest fragments of Hebrew literature in the Bible, and there seems to be no reason to question its authenticity as a Davidic song. The poem displays strong emotion, particularly concerning Jonathan’s death (II Sam. 1:25b-26).

The figure of Saul never emerges clearly from the limited information provided by the early tradition. There is no record of his early years or of his family life, and he is introduced as a grown man of immense stature, a well-known figure who tilled his family estates. There can be no question of his leadership ability, for time and again he united the Hebrew people to fight against superior armies and weapons, and led them to victory. Long after he had been succeeded by David there remained a group fearlessly loyal to his memory. Clearly Saul was given to violent emotional expression. His vehement response to the news of the siege of Jabesh-Gilead, his violent anger against the priests of Nob, his moods of deep depression and his brooding hatred of David, provide some insight into the intensity of his feelings. His devotion to Yahweh never waned, and when he realized that he had been abandoned by his god, he emerges as a most tragic figure, desperately seeking some means to restore relationships.

The powers inherent in the kingship did not, apparently, encourage him to exploit the people. His capital city of Gibeah, a few miles north of Jerusalem, has been excavated (assuming Tell el-Ful is Gibeah),15 and a fortress often identified as Saul’s palace appears to have been little more than a large two-story dwelling constructed on the foundations and outline of an earlier Philistine building. The structure was about 115 by 170 feet, and the largest room about 14 by 23 feet. Pottery found in the ruins was similar to that in common use in Saul’s day. The usual household equipment – spinning whorls for making yarn, grinding querns to produce flour, storage jars for oil, wine and grain, a game board, some sling-stones, and two bronze arrowheads – would seem to indicate, in the absence of other evidence, that Saul’s monarchical headquarters were simple indeed.

Endnotes

- E.g., the saying "is Saul among the prophets?" (I Sam. 10:11; 19:24) ; David’s flight to Achish of Gath (I Sam. 21:11-16; 27:1 ff.) ; the Ziphite treason (I Sam. 23:19-28; 26:1 ff.) ; David’s sparing of Saul’s life (I Sam. 24; 26) ; Yahweh’s rejection of Saul (I Sam. 13:7-15; 15).

- An incubation rite is one in which a worshiper sleeps in a shrine or other holy place to receive a message from the god of the shrine through a dream or vision.

- The term "ark" is an anglicized word from the Latin arca, a "chest" or "box," used in the Vulgate to translate the Hebrew word ‘aron. No exact description of the ark is given in the Samuel section, but the D writer stated later that it was made of acacia wood and contained the two tablets of the decalogue (Deut. 10: 1-5), and the P writer, who labelled it "ark of testimony," described it later still in detail (Exod. 25:10-21; 37:1-9). That it had cultic significance is clear from Psalm 132:8. For further details, see "Ark of the Covenant," The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible and the bibliography listed there.

- Progressive interpretation can be discerned in I Sam. 4:8 where the words "woe to us" of vs. 7 are expanded by an account of Yahweh’s feats in Egypt. The names "Phineas" and "Hophni" in vss. 11 and 17 are details added by a scribe who failed to alter the Hebrew syntax to make it conform to his changes.

- Cf. Moabite inscription, p. 167 where sacred items of Yahweh are brought before Chemosh.

- Other additions can be found in 6:17 f., an explanation of the symbolism of the great stone, and also in 7:2.

- The Hebrew verb "to anoint" (mashah) is the root from which the word "messiah," meaning "anointed one" is derived. The king is, therefore, an "anointed one," a messiah.

- The presence of the ark at Michmash contradicts the tradition that it remained at Kireath-Jearim until David had it removed to Jerusalem (II Sam. 6:2 ff.). W. R. Arnold, Ephod and Ark, Harvard Theological Studies, III (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1917), has suggested that there may have been more than one ark. However, in view of the fact that the LXX reads "ephod" rather than "ark" at this point, the question must be left open.

- Note in vs. 11 the motif of the hidden hero.

- The Hebrew term mohar, "marriage price," refers to the sum paid by the groom to the father of the bride. The bride became the property of the groom, bringing with her into marriage her own possessions, and probably in the case of Michal, personal servants. The mohar was by way of compensation. Marriage was not a matter of religious observance, but a civil contract. Cf. DeVaux, Ancient Israel, pp. 24-38.

- The ancient sling must not be confused with the modern "slingshot" (see illustration). Sling stones found in Palestinian excavations vary from the size of a golfball to something larger than a tennis ball.

- Here two traditions seem to have been combined, the second expanding the details of the first (20:1-17, 24-34; and 20:18-23, 35-42).

- This particular account probably circulated orally for it appears in a different setting in I Sam. 26:1-25. Both stories may rest on sound historical memory.

- Distinctions in concepts of deity need to be kept in mind. Monotheism means belief in one god and denial of the reality or existence of any other. Monolatry is the belief in and worship of one god without denial of the reality or existence of other gods – a concept prevalent among the Hebrews until after the Exile (cf. Deut. 32:8; Jer. 5:19). Henotheism, which ascribes power to several gods in tum by virtue of one absorbing the other, should not be confused with monolatry. For further discussion, cf. Meek, op. cit., pp. 204 ff.

- Cf. Paul W. Lapp, "Tell el-Ful," BA, XXVIII (1965), 2-10.

Old Testament Life and Literature is copyright © 1968, 1997 by Gerald A. Larue. All rights reserved.

The electronic version is copyright © 1997 by Internet Infidels with the written permission of Gerald A. Larue.