(2nd ed., 2022)

ABSTRACT: This essay is an attempt to recover the oldest meaning of the cross of Jesus and that of Jesus’ resurrection in their historical context. The paper argues that penal substitution, the popular conservative evangelical interpretation of the cross, is incorrect, and furthermore that it results in interpretive absurdities when applied to the text/evidence. Penal substitution claims that a just God lacks the ability to forgive, and so requires punishment for sin, where the innocent Jesus was substituted for us sinners and brutally bore the punishment for our sins, wiping our sin debt clean. By contrast, this essay presents a nonpenal substitution participation crucifixion model, where Jesus is understood to be our willing victim as a catalyst for opening our eyes to our hidden “satanic influenced vileness” and for encouraging repentance. This problem is specifically outlined in the dense passage of Mark 15:10-15, a passage dis-closing the hidden vileness of the easily incited crowd, the hidden jealousy of the religious elite, and the utter lack of commitment to justice of crowd-placating Pilate, who releases Barrabas, a known killer of Romans, but who tortures and executes Jesus without a confession or having found that Jesus did anything wrong. The oldest meaning of the resurrection of Jesus will also be shown to be what Jesus’ disciples took to be evidence for overcoming death in a blessed way, and empowering us to live righteously. The cross/resurrection argument will further be contextualized in a Second Temple framework of apocalypticism and demonology/superstition to show that the original meaning of the cross and resurrection is so divorced from most modern Christian frameworks and beliefs that many modern Christians would reject the heart of what their ancient counterpart would hold as fundamental to living a good and holy Christian life. The upshot is that the usual modern conservative interpretations of the cross and resurrection bear no, or at least merely superficial, relation to the original ancient ones. Basically, this essay argues for an understanding of the cross that is a nonpenal substitution understanding that emphasizes (1) love for enemies (Matthew 5:43-48) that is (2) manifested in such ideas as those expressed in Luke 23:34, which results in (3) transformations like those found in Luke 23:47 and Mark 15:39. This is all perfectly reasonable, but it becomes absurd when we come to see it in an ancient demonology framework.[1]

- The Old Rugged Cross: Penal Substitution vs. Participation

- Creating the Meaning of the Cross: Haggadic Midrash/Mimesis

- But the Question is: Why was Mark Looking to Isaiah 53?

- The Martyr Model of the Cross

- Satan and the Crucifixion/Resurrection

- The Archons of this Aion

- Satan in Paul’s Epistles

- The Resurrection: Christ in You to Empower You in Resisting Satan’s Influence

- God’s Plan of Redemption

- Conclusion

1. The Old Rugged Cross: Penal Substitution vs. Participation

“Atonement is the central doctrine of the Christian faith, and penal substitution is the heart of this doctrine.” (Roger Nicole)

“The doctrine of penal substitutionary atonement of Jesus Christ can be abandoned only by eviscerating the soteriological heart of historic Christianity.” (Timothy George)

“Deny the vicarious nature of the atonement—deny that our guilt was transferred to Christ and he bore the penalty—and you have in effect denied the ground of our justification. If our guilt was not transferred to Christ and paid for on the cross, how can his righteousness be imputed to us for our justification? Every deficient view of the atonement must deal with this same dilemma.” (John MacArthur)

“The doctrine of penal substitution could be expunged from the biblical witness only by a perverse and criminal mistreatment of the sacred text or a tendentious distortion of its meaning.” (Greg Bahnsen).

“The belief that the cross had the character of penal substitution…. I am one of those who believe that this notion takes us to the very heart of the Christian Gospel.” (J. I. Packer)

(all above references cited in Pulliam, 2011, p. 182)

If you are a conservative evangelical Christian, you most likely believe in the penal substitution understanding of what was accomplished by Jesus on the cross. Penal substitution is the core of the evangelical Christian faith on which everything rests, and from which everything proceeds. What is penal substitution? Ken Pulliam explains it as follows:

God’s holiness demands that sin be punished. God cannot remain just and forgive man without punishing his sin. That would ignore the seriousness of sin. Therefore, God sent his son to bear the punishment for man’s sin. Jesus vicariously bears the punishment for man’s sin. Once sin has been punished, then God can forgive man without compromising his holiness or justice. (Pulliam, 2011, p. 181)

Some key passages that are often pointed to by conservative scholars in favor of the penal substitution model of the death and resurrection of Jesus include:

- Romans 3:23-26—”All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God; they are now justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as a sacrifice of atonement by his blood, effective through faith. He did this to show his righteousness, because in his divine forbearance he had passed over the sins previously committed; it was to prove at the present time that he himself is righteous and that he justifies the one who has faith in Jesus.”

- 2 Corinthians 5:21—”For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God.”

- Galatians 3:10, 13—”All who rely on works of the law are under a curse; for it is written, ‘Cursed be every one who does not abide by all things written in the book of the law, and do them.’ … Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law, having become a curse for us—for it is written, ‘Cursed be every one who hangs on a tree.'”

- Colossians 2:13-15—”And you, who were dead in trespasses and uncircumcision of your flesh having canceled the bond which stood against us with its legal demands; this he set aside, nailing it to the cross. He disarmed the principalities and powers and made a public example of them, triumphing over them in him.”

- Mark 10:45—”For even the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.”

- Mark 15:39—”And when the centurion, who stood facing him, saw that in this way he breathed his last, he said, ‘Truly this man was the Son of God!'”

- Mark 14:24—”And he said to them, ‘This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many.'”

- Mark 15:37-39, where Jesus dies and the curtain in the Temple is immediately ripped in half. This curtain is to be understood as separating God from humanity—he was believed to dwell in the Holy of Holies behind the curtain, and only the high priest could go into his presence in that room, and that only once a year on the Day of Atonement to make a sacrifice for the people’s sins. Now, with the death of Jesus, in Mark, the curtain is destroyed, and people thereafter do have access to God.[2]

- Mark 15:6-15, where Jesus is killed instead of Barabbas. This is sometimes pointed to as penal substitution imagery. But this isn’t a good fit because Jesus wasn’t killed making Barabbas any less guilty, rather the prisoner Barabbas is able to go free because of Jesus’ death. This will be related below to people being a prisoner/hostage to demonic influence. Innocent Jesus wasn’t killed for sins Barabbas committed. Rather, in a miscarriage of justice Barabbas, a known killer of Romans, was released to placate and flatter the crowd, just like in a miscarriage of justice Pilate executed Jesus without cause to flatter an placate the crowd and Jewish elite.

The penal substitution interpretation is the core of the conservative evangelical Christian faith. But it’s probably historically unrelated to what the oldest Christian beliefs were about the cross. In fact, the penal substitution model only fully appeared a thousand years after Jesus, and was long predated by the ransom model (Morrison, 2014).

Devastatingly so for conservative Christian scholars and Christ myth advocates, critical scholars generally think that Jesus did not preach about his crucifixion or resurrection during his lifetime, or about the idea that these events had some special “saving” component for humanity.[3] There are numerous lines of evidence for this. One important one in the Gospel of Mark is that Jesus’ disciples seemed to have no clue that Jesus was supposed to be arrested and die as part of the mission. We can infer this from the fact that Mark says that Jesus’ disciples got violent at the arrest. Why would this violence have happened if they had thought that Jesus was supposed to be arrested? Mark obviously had an issue with reconciling the central event of Jesus’ crucifixion with the problem that no one knew that it was supposed to happen, and so Mark invented the obviously ad hoc argument that Jesus had repeatedly explained in clear terms that the crucifixion and resurrection were coming, but that the disciples were too clueless and stupid to understand him. The obvious inference here is that the disciples were well known for having clashed with the arresting party, and Mark had to explain this away. A similar line of evidence is that at the earliest stage of the Q source (the material common to Matthew and Luke that didn’t come from Mark), Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection are not even mentioned. Conservative Christian scholars and Christ myth advocates are quite uncomfortable with such evidences because their whole approach falls apart if the crucifixion and resurrection are not basic to the religion. Carrier has this problem, so he denies that any history can be distilled from the Gospels, and denies that there is a Q source.

Regarding the cross, there are two basic models: the penal substitution or vicarious atonement model, and the moral influence model. Here is a helpful brief Wikipedia article on moral influence. Penal substitution is basically the idea from conservative (current and former) Christians and mythicists that the original Christians thought that we deserved to die for our sins, but luckily for us, Jesus died in our place so that we’re saved! The moral influence model counters with the logical point that if punishing an innocent child in Africa for the crimes of a felon in Chicago obviously doesn’t serve justice, how would punishing an innocent Jesus for our sins serve justice? Moreover, it imputes on the Jewish tradition a God who can’t forgive, which runs afoul of any number of Hebrew scripture portraits, like the penitential Psalms or the story of Jonah.

There seem to be a couple of things going on. Paul says in 1 Corinthians that he received (presumably from James, Peter, and John, son of Zebedee) that Christ died “for” our sins. On the one hand, this seems to reflect the Yom Kippur sacrifices of the pure goat and the violent death of the scapegoat, as well as a moral component where Jesus’ death awakens us to our moral depravity and inspires repentance. Thus Jesus dies “for our sins” to be made conspicuous so that we can repent. In this way—as in the case of Socrates in his last words to Crito—there seems to be two levels: a superficial level of Jesus dying “for our sins,” erasing them like a super blood magic version of the Yom Kippur goats, and a more essential version of making our hidden sins conspicuous so that we can work on them. After all, forgiveness is meaningless if we don’t have a contrite heart, since we will just sin again. Mark satirizes the penal substitution view of the cross with the absurd fictional account of Barabbas being released instead of Jesus. From a literary point of view, the idea that the cruel historical Pilate would release Barabbas, a known killer of Romans, thereby condemning Jesus—whom he found no fault with, just to placate a crowd of Jewish subjects that the historical Pilate couldn’t have cared less about—emphatically shows that the Yom Kippur sacrifices result in the very opposite of justice. We need to see beyond this vicarious atonement surface level to a more noble Socratic moral influence ethics, this being the key issue that conservative Christians and mythicists get wrong. This is why the early Christians were an anti-temple cult.

I think that what we’re getting is a replacement of the unethical Jewish Yom Kippur sacrifice tradition with the pagan death of Socrates and the impaled just man in Plato’s Republic tradition, the Republic being the most famous book in the ancient world. With Socrates, we have a pagan unjust death and what it inspires, like the transfiguring of the pagan Roman soldier at the cross. Socrates’ famous last words were a prayer of thanksgiving to divine Asclepius for the hemlock poison, presumably because it cures him of the prison (sema) of his body (soma), and will work as a catalyst to change the society that was responsible for his unjust death (pharmakon: poison and cure). Similarly, the impaled just man in the Republic was a challenge: how could a just man who is horribly killed for his ideals have a more desirable life than that of an unjust man who has obtained all of the pleasures of the world? Clearly, the answer conveyed is: if his death meant something.

Similarly, there seems to be an invented literary pair in Mark between the desperate Gethsemane prayer and the Psalm-22-based-cry from the cross in order to emphasize that despite Jesus’ desperation, he ultimately trusted in God. Two points are noteworthy. First, obviously, if Jesus thought that the cup could be taken from him, Mark is winking that Jesus didn’t think that he needed to die for God’s plan to be realized. But ultimately, it was probably well known that Jesus was squealing like a pig on the cross, and this didn’t fit with the later salvific mission interpretation of the cross, so Mark started spinning things: Jesus was terrified, but this just shows how obedient Jesus was to God to declare God’s will rather than his own. We thus see a contrast between the cup that Jesus wished were taken from him in Gethsemane and the cup of poison hemlock that Socrates took:

Socrates in the prison cell in Athens, according to Plato’s account, took his cup of hemlock “without trembling or changing colour or expression” [Phaedo, trans. H. N. Fowler, pp. 117-118)]. He then “raised the cup to his lips and very cheerfully and quietly drained it” [(Ibid., p. 118)]. When his friends burst into tears, he rebuked them for their “absurd” behavior and urged them to “keep quiet and be brave.” He died without fear, sorrow or protest. (Stott, 1986, p. 88)

Luke thus changed the panic stricken Jesus of Mark’s cross to a Socratic calm resolute one because it made better theological sense.

Conceptually, even on a cursory examination, the penal substitution interpretation of the cross is highly problematic. For one thing, it is logically incoherent. It appeals to God’s desire/demand for justice, but makes a claim that is fundamentally unjust—by analogy, how does a judge punishing an innocent child in Africa for a robbery committed by a felon in Boston satisfy/serve justice? A judge imposing such a punishment would be incoherent and unjust. Also, it decontextualizes Christianity from the Hebrew scripture tradition because one thing that God can always do in Judaism is forgive. We have an analogy from Psalms that one person can’t pay another’s ransom (contrary to what substitutionary atonement assumes), but it is up to the grace God to deal with death (or forgive sins in the case of the New Testament):

Truly no man can ransom another,

or give to God the price of his life,

8 for the ransom of their life is costly

and can never suffice,

9 that he should live on forever

and never see the pit. …

15 But God will ransom my soul from the power of Sheol,

for he will receive me. (Psalm 49:7,15 ESV)[4]

In fact, Keith Giles points out that there would be a number of reasons why Jesus having been a vicarious penal substitution atonement sacrifice would have contradicted scripture:

- Sin offerings had to be female [not male] animals according to Leviticus 4:32;

- Sin offerings could not have any wounds according to Leviticus 22:22;

- Sin offerings had to be taken to the priest and offered on the altar inside the Temple according to Deuteronomy 12:13-14;

- Human sacrifices for sin were an abomination to God according to Deuteronomy 12:31; 18:10 and Ezekiel 16:20;

- God does not allow any man to die for the sins of another according to Psalm 49:7-8;

- All are accountable for their own sins. A Father cannot take responsibility for the sins of his children according to Ezekiel 18:20; and

- The sacrifice that took away the sins of the people was NOT put to death but set free in the wilderness according to Leviticus 16:9-10.

With the exception of 7 (the scapegoat did die a horrible death), Keith Giles seems generally reliable here, and so if Jesus’ death is to have salvific meaning, it’s not as penal substitution atonement. Giles sums up the case against penal substitution as follows:

Now, this doesn’t mean that our sins are not forgiven. Nor does it mean that the crucifixion didn’t play an important role in establishing our forgiveness.

Our sins are forgiven for one simple reason: Jesus forgave us.

What Jesus did was only what he saw the Father doing. And what do we see the Father doing when we look at Jesus? We see the Father [through Jesus] forgiving everyone he encounters, no matter what.

God’s response to our sin is forgiveness. We are forgiven.

Jesus really is “the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world” because Jesus takes even the worst possible sin we can throw at him—the torture and murder of an innocent man [even the son of God himself]—and his response is this: “Father, forgive them for they know not what they do.”

And the result? God answers this prayer. We are all forgiven.

Where was God on the day we crucified Jesus? “God was in Christ reconciling the World to Himself, NOT counting our sins against us.” [2 Cor. 5:19]

But, I thought there was no forgiveness without the shedding of blood?! Doesn’t the Bible tell us this?

Yes, and no.

What it says [in Hebrews 9:22] is that ‘under the Law’ there is no forgiveness apart from the shedding of blood. But we are not under the Law. [Something the author of Hebrews takes great pains to point out].

Not only that, there are at least 7 examples where the forgiveness of sins WAS proclaimed WITHOUT the shedding of blood.

For example:

Application of oil (Lev 14:29)

Burning flour (Lev 5:11-13)

Burning incense (Num 16:41-50)

Payment of money (Exod 30:11-16)

Gifts of jewelry (Num 31:48-54)

The release of a live animal [the scapegoat] (Lev 16:10)

Simple appeals to God through words/prayers (Exod 32:30)

So, not only does PSA theory have very little scriptural support for the notion that God ordained that Jesus should be sacrificed on the cross to atone for ours sins, we have numerous examples in scriptural where almost every single point of this atonement theory is soundly contradicted.

Rather than complicate what happened on the cross, the New Testament authors make it very simple:

We murdered Jesus. God raised him from the dead. [See Acts 2:23; 3:15; 5:30; 10:39; 13:28]

We sinned. God forgave us. [See Ps. 103:12; 1 Cor. 13:5; John 1:29; Luke 7:48; Matt. 9:5; 2 Cor. 5:19; Heb. 10:17]

Jesus took the worst we had to offer and still extended his boundless love, grace and forgiveness to us all—before, during and after the crucifixion event.

Where does that leave us now?

Forgiven. Accepted. Redeemed. Qualified. Reconciled.

And—most of all—loved beyond measure, scope, expectation or imagination. [Eph. 3:18; Rom. 8:38-39; 1 John 3:1]

PSA is bad news. The Gospel of Christ is Good News. (Giles, 2020)

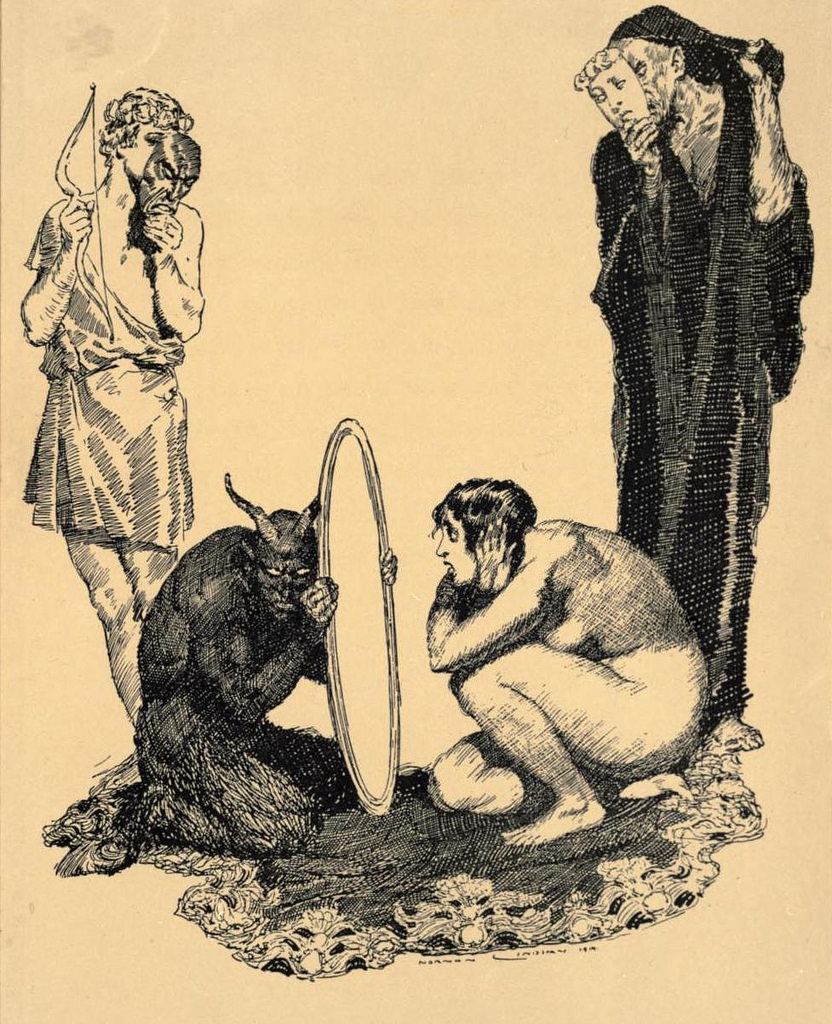

As we will see below, it is in fact God sending Jesus to die that becomes the ransom (i.e., pays the price) that breaks the spell of Satan, who was holding the minds of humans hostage. But this has nothing to do with substitutionary atonement; rather, it concerns turning the mirror on oneself and dis-covering vileness, inspiring repentance so that God can forgive. A “payment of the sin debt” interpretation argues that Jesus (either as God incarnate or a highly favored human prophet) paid the punishment for sin that we deserved because a just God demanded retribution for our sin. But Psalm 49:15 doesn’t talk about a death that satisfies God’s demand for justice; rather, it concerns a price paid that breaks the stranglehold of death, which in the New Testament constitutes sin, e.g., in Romans 8. Look at verses 5-6: “For those who live according to the flesh set their minds on the things of the flesh, but those who live according to the Spirit, the things of the Spirit. For to be carnally minded is death, but to be spiritually minded is life and peace.” So we read in Barnes’ commentary on Psalms 49:15:

But God will redeem my soul from the power of the grave—literally, “from the hand of Sheol;” that is, from the dominion of death. The hand is an emblem of power, and it here means that death or Sheol holds the dominion over all those who are in the grave. The control is absolute and unlimited. The grave or Sheol is here personified as if reigning there, or setting up an empire there.

It seems that the drama of the crucifixion that unfolded in the New Testament was a copying or mimesis/haggadic midrash of Psalm 49, except death is reinterpreted as sin and the dominion of Satan. The central New Testament theme is thus pure literary invention out of the Hebrew scriptures. Mark uses the same technique when he imitatively portrays John the Baptist as the new and greater Elijah, as does Matthew when portraying Jesus as the new and greater Moses. But we should not think that the first Christians read Psalm 49:15 as referring to a Trinitarian “God incarnate Jesus” as defeating death/sin. Rather, they likely read it as the human prophet Jesus enacting God’s will. There is a similar God/David expression in 1 Chronicles 14:11: “So he went up to Baal-perazim, and David defeated them there. David said, ‘God has burst out against my enemies by my hand, like a bursting flood.'” Clearly, here God acts through David; the implication is not that David is God.

God manifesting through people is a pretty consistent Jewish theme with God acting through people to demonstrate his power and glory. For example, Moses defeats the magicians of Pharaoh because the Jewish God is in charge, not the Egyptian gods. And Elijah demonstrates the sovereignty of the Jewish God by defeating the prophets of Baal. Jesus displays the superiority of the Jewish God by overcoming the will of Rome and its son of God Caesar by Jesus being resurrected following the Roman execution of Jesus. Grammatically, Paul points out that Jesus is being raised by God, that it is not something that Jesus is doing to himself, and so there is nothing of a Trinity metaphysics going on here. That was a later development, and one that isn’t even logically coherent because to say that Jesus was fully man, fully God, and fully Holy Spirit imputes 300% being to Jesus, which is mathematical gibberish. Conservatives thus say that the Trinity is a mystery, although I would say that it’s more meaningless than mystery.

Finally, it’s unclear what proponents of the conservative interpretation of the cross think Jesus’ death accomplished, since it is basically unrelated to whether one goes to Hell or not, and without the resurrection it is meaningless (1 Corinthians 15:17). The death of Jesus is of no effect (even in conservative Christian theology) if you commit a crime and don’t repent. If you do repent, then you are forgiven; so if forgiveness works, why did Jesus have to die in the first place? Such an interpretation results in the ethical absurdity that a person can be paradigmatically moral their whole life, and yet still go to Hell if they have incorrect beliefs, whereas if Hitler had quietly repented and asked for forgiveness before he died, he would be in paradise right now. The penal substitution model is certainly an easy way to attain a holy life, but it is unlikely to be historically biblical.

A more reflective interpretation of the cross has been proposed by scholars like Derek R. Brown (2011) and Paula Fredriksen (2018) in their studies on Paul, which concluded that what the cross actually did was render a proleptic judgment on all evil powers—the eschatological defeat of Satan (Christ the Victor). There is certainly merit in this reading, but it results in the interpretive absurdity that Christ’s death nullified the power of Satan/demons, but Satan and the demonic were still in control (see, for instance, Fredriksen, 2018, pp. 88-89).

This essay proposes an interpretation of the cross and resurrection that sees Luke-Acts as an exemplar for reading Paul and Mark where what is at issue is not reconciling man with God by wiping away the sin debt, but rather how Jesus as the specially chosen paradigmatically holy man of God, through his horrific torture and unjust murder by society, dis-closes (aletheia) the hidden satanically/demonically vile nature of humanity. This inspires repentance and change, an awakening of what Paul called the law God wrote on human hearts (Romans 2:14-15). The repentance and change mirrors that which followed Socrates’ death, or that which ensued from Plato’s paradigmatically righteous impaled just man in book 2 of the most famous book in the ancient world, Plato’s Republic.

2. Creating the Meaning of the Cross: Haggadic Midrash/Mimesis

To begin to explore this, there seems to have been an adoption by the New Testament writers of the Greek mimesis technique (which in Second-Temple Judaism could perhaps be called Haggadic Midrash), the practice of rewriting old stories in order to show that the copy is superior to the original. So, for example, as Bart D. Ehrman points out, Matthew’s story of Jesus retells the story of Moses to present Jesus as the new and greater Moses (Ehrman, 2012). Similarly, Mark frames his portrayal of John the Baptist in the account of Elijah, which had the added bonus of paralleling Jesus with Elisha, who was Elijah’s successor and superior (Price, 2005). This technique has profound consequences for the New Testament portrayal of the crucifixion and resurrection.

For example, according to most evangelical Christian scholars, likely the clearest Old Testament prophecy about Jesus is the entire 53rd chapter of Isaiah. Isaiah 53:3-7 is especially unmistakable. However, the consensus of critical scholars is that 2 Isaiah (what scholars call Isaiah 40-66) wasn’t making a prophecy about Jesus (Spong, 2011). Mark was doing a haggadic midrash, inventing a story about Jesus by using Isaiah 53 as a model. So, Mark depicts Jesus as one who is despised and rejected, a man of sorrow acquainted with grief. He then describes Jesus as wounded for our transgressions, bruised for our iniquities. The servant in Isaiah, like Jesus in Mark, is silent before his accusers. The book of Isaiah says of the servant with his stripes that we are healed, which Mark turned into the story of the scourging of Jesus. This is, in part, where penal substitution atonement theology comes from, but it would be silly to say 2 Isaiah was talking about atonement. The servant is numbered among the transgressors in Isaiah, so Jesus is crucified between two thieves.

Further, in a peer-reviewed article for the Encyclopedia of Midrash, Robert M. Price argues:

[T]he substructure for the crucifixion in chapter 15 is, as all recognize, Psalm 22, from which derive all the major details, including the implicit piercing of hands and feet (Mark 24//Psalm 22:16b), the dividing of his garments and casting lots for them (Mark 15:24//Psalm 22:18), the “wagging heads” of the mockers (Mark 15:20//Psalm 22:7), and of course the cry of dereliction, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mark 15:34//Psalm 22:1). (Price, 2005, p. 553)

The Septuagint, a Jewish translation of the Hebrew Bible into Koine Greek made before the Common Era, has “they dug my hands and feet,”, which some commentators argue could be understood in the general sense as “pierced.” Notably, the team of specialist scholars who put together the Jewish Annotated New Testament (2nd edition) also affirm the dependency of Mark’s crucifixion narrative on Isaiah 53 and Psalm 22.

3. But the Question is: Why was Mark Looking to Isaiah 53?

If you were to ask a Christian child the meaning of the cross, they would probably say something like “Jesus died for my sins.” This isn’t the end of the conversation, though, but rather the beginning of it. We see a similar statement in the oldest references to Jesus’ death, the pre-Pauline Corinthian creed that Paul cites, which says “Christ died for our sins according to scriptures.” But what does “for” mean here? Does for mean that Christ died in substitution for us, in order to pay the debt of our sins? Or does it mean that Christ died because of our sins, that our corruption resulted in the unjust horrific death of the highest favored man of God? We started thinking about Isaiah 53 above, so let’s keep the ambiguity of “for” in mind and think about that passage.

Perhaps an initial question is what “sin” means in the context of the New Testament. The most direct definition is when we read: “Everyone who commits sin is guilty of lawlessness; sin is lawlessness” (1 John 3:4). So, sin is lawlessness. And what is this law that is being transgressed even to the degree of being in opposition to God? Jesus says that the essence of the law is loving God with all of your heart and loving your neighbor as yourself, even to the point of love of the enemy. An exemplar of this “sin” would be the world that unjustly turned on Jesus even though he was God’s specially chosen one: Pilate denied him justice; the Jewish supreme council conspired against him, though they knew that it was not God’s will to have Jesus killed; the crowd turned on him; and his disciples repeatedly denied (e.g., Peter), betrayed (e.g., Judas), failed (e.g., violence at arrest), and abandoned Jesus. For Jesus’ death to rescue us from “sin” specifically means washing the scales from our eyes so that we can soberly see our failings, thus serving as a catalyst for change. If we don’t clarify what we mean by “sin” and “law” in a Christian context, we fall back on the Old Testament commandments and animal sacrifice purity, and completely misunderstand the New Testament as penal substitution. Christian law isn’t followed because you fear punishment, but because “If you love me, you will keep my commandments” (John 14:15). It is this sense that Jesus was sinless. Though a person is basically guilty of sin just in virtue of living (“if your eye offends you pluck it out” [Matthew 18:9]), Jesus was blameless in the sense that he showed love of God and humanity—the pillars on which all the commandments stand—in an exemplary way. Despite every fiber of his being wanting to flee and hide, he submitted to God in Gethsemane, a perfect relation to his “commanding officer” that was recognized by the transfigured “soldier” at the cross in Mark. In Luke this becomes the soldier being transfigured by Jesus showing perfect forgiveness.

An important starting point is how we’re going to interpret the key word in Isaiah 53:5. Does (i) “for” = “in place of,” or does (ii) “for” = “because“? For the conservative evangelical reading to hold, “for” has to mean “in place of.” But it’s ambiguous. We could translate:

“But he was pierced in place of us for our transgressions,

he was crushed in place of us for our iniquities;

the punishment that brought us peace was on him,

and by his wounds we are healed.”

vs.

“But he was wounded (for) because of our crimes,

crushed (for) because of our sins;

the disciplining that makes us whole fell on him,

and by his bruises we are healed.”

So, “for” can be understood in either way in Isaiah 53:5—as in place of, or because—and so we need to appeal to the context. In other words, “FOR” can mean:

- “In place of”: go to the store for me; “On behalf of”: speaks for the court

…but just as possible is reading “for” this way:

- “Because of”: I can’t sleep for the heat; I can’t win for trying.

The consensus of critical scholars agrees that the passage from 2 Isaiah above is referring collectively to Israel, not the vicarious atonement of the messiah (as conservatives suggest). So, as Marshall Roth explains, one possible reading is:

Isaiah 53 is a prophecy foretelling how the world will react when they witness Israel’s salvation in the Messianic era. The verses are presented from the perspective of world leaders, who contrast their former scornful attitude toward the Jews with their new realization of Israel’s grandeur. After realizing how unfairly they treated the Jewish people, they will be shocked and speechless…. Indeed, the nations selfishly persecuted the Jews as a distraction from their own corrupt regimes: “Surely our suffering he did bear, and our pains he carried…” (53:4) [emphasis mine] (Roth, 2011)

If this is right, it could be why Mark is looking to Isaiah to construct the crucifixion narrative. In Mark, the Roman soldier looks up at Jesus, who was faithful unto death despite his plea in Gethsemane, and says “Truly, this man was God’s son.” This could be interpreted as vicarious atonement, but it could just as easily refer to the transformative experience of the soldier seeing his culpability in the holy Jesus unjustly crucified that brings about the realization of one’s hidden vice and results in repentance. This is precisely the generally accepted meaning of the cross in Luke.

The idea of the mighty nations being humbled before the chosen of God certainly has precedence in Hebrew scriptures (e.g., in Micah 7:16). The nations who confronted God’s people were humbled (i.e., “put their hands on their mouth) (e.g., Judges 18:19; Job 21:5; 29:9; 40:4). It will be so again because under His renewed covenant, people go forth in His power and presence (cf. Psalm 2).[5] As we will see later with Paul, it will be the Christian community, not just Jesus, that is victorious over Satan.

So, perhaps Jesus “fulfilled” Isaiah 53, not as a prophecy of Jesus as a penal substitution atoning sacrifice, but rather “filled it full of meaning”—which, according to Ehrman (2015), is what fulfilled means in a Jewish religious context. Regarding whether to choose “for” as “because of” or “in place of,” Roth adds:

Isaiah 53:5 is a classic example of mistranslation [by conservative Christians]: The verse does not say, “He was wounded for our transgressions and crushed for our iniquities,” which could convey the vicarious suffering ascribed to Jesus. Rather, the proper translation is: “He was wounded because of our transgressions, and crushed because of our iniquities.” This conveys that the Servant suffered as a result of the sinfulness of others—not the opposite as [conservative] Christians contend—that the Servant suffered to atone for the sins of others. Indeed, the [conservative] Christian [interpretation] directly contradicts the basic Jewish teaching that God promises forgiveness to all who sincerely return to Him; thus there is no need for the Messiah to atone for others (Isaiah 55:6-7, Jeremiah 36:3, Ezekiel chapters 18 and 33, Hosea 14:1-3, Jonah 3:6-10, Proverbs 16:6, Daniel 4:27, 2 Chronicles 7:14) [emphasis mine]. (Roth, 2011)

This is important, but we will explore it later with James McGrath. Portraying God as unable to forgive runs against the grain of Hebrew scriptures.

So, Roth gives a helpful analysis as to why the reader may not need to take Isaiah 53 to refer to penal substitution. Now Andrew Perriman argues that the key to understanding Isaiah 53 is that the innocent servant, Israel, also suffers because of or as consequence of the past actions of Israel, not for them in the sense of substituting for others. Perriman explains the meaning of the passage in its historical context:

It’s an integral part of the story of the exile and the return from exile.

In view of this, I suggested that the suffering servant of Isaiah 52:13-53:12 is best understood as the community of Israel or Jacob that “grew up” in Babylon as a consequence of the sins of the previous generation. They have borne the punishment of Israel, but they will also be the means of redemption and the basis for a new future: “when his soul makes an offering for guilt, he shall see his offspring; he shall prolong his days; the will of the LORD shall prosper in his hand” (Isaiah 53:10; cf. Isaiah 53:12 LXX). [emphasis mine] (Perriman, 2019)

In fact, the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Old Testament that the New Testament writers were working from, renders Isaiah 53:5 as: “He was wounded because of our acts of lawlessness, and has been weakened because of our sins” (Pietersma, 2007, p. 865). “For” in the sense of “in substitution for us” doesn’t work with the Greek here. “Because” is the correct reading. So, clearly, from Roth and Perriman above we see in Isaiah 53 that the suffering servant refers to Israel as a whole, not the individual messiah that penal substitution advocates want, and that the innocent servant suffers because of others, not in substitution for others. As we will see, this fully supports an interpretation of the cross as an innocent suffering because of others, not in penal substitution for others. In other words, there is good reason why Mark modeled his crucifixion narrative on Isaiah 53, just not any reason that conservative evangelicals want.

Moreover, Breytenbach (2009, p. 348) shows that lying behind Romans 4:25—if the Septuagint version of Isaiah 53:4-6, 12 is at work there—is the idea that Christ died “because” of our trespasses rather than was handed over “for” our trespasses, the latter constituting the incorrect translation of the New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition (NSRVue). Consider the Moises Sylva translation:

This one bears our sins

and suffers pain for us,

and we accounted him to be in trouble

and calamity and ill-treatment.

But he was wounded because of our acts of lawlessness

and has been weakened because of our sin;

upon him was the discipline of our peace;

by his bruises we were healed

All we like sheep have gone astray;

a man has strayed in his own way,

and the Lord gave him over to our sins (Septuagint Isaiah 53:4-6, Sylva translation)

Therefore he shall inherit many,

and he shall divide the spoils of the strong,

because his soul was given over to death,

and he was reckoned among the lawless,

and he bore the sins of many,

and because of their sins he was given over (Septuagint Isaiah 53:12, Sylva translation)

Romans 4:25 is a much disputed translation. Agreeing with my translation of cause/because, rather than for, are NLT, NKJV, NASB, ISV, and YLT. Translations that disagree and use for include the NRSVue, NIV, and ESV.

To relate this to Paul’s citation of the beginning of the Corinthian Creed, I reference in note 9 that Blasi translates this as “Christ died because of our sins according to the scriptures,” rather than the more common “Christ died for our sins” (i.e., paying the sin debt). I think that Blasi is right to highlight the “because”—but we should then reintegrate the “for” in a non-penal-substitution manner. Why?

Any number of analogies show the incoherence of penal substitution. Conservative Christians claim that Jesus had to die to serve God’s mandate for justice: sin must be punished and not simply forgiven. But how would punishing an innocent child in Africa for the wrongs of a felon in Chicago serve justice? Similarly, Christ’s sacrifice supposedly wipes the sin slate clean for new believers. If they sin after that, they can repent. But if repentance works, why did Jesus have to die in the first place? Jesus was executed as “King of the Jews” (Mark 15:26), the Davidic heir (Romans 1:3) who was specially favored and chosen by God to restore David’s throne. Jesus proved who he was through his healings and miracles. For a man to believe that Jesus was the Son of God in this sense meant that he saw in himself the angry crowd, the corrupt religious elite, and the indifferent-to-justice Pilate who horribly tortured and executed God’s chosen one. Why? Seeing the actuality/potential for the crowd/religious elite/Pilate in ourselves is the recognition that inspires the change of heart and repentance: walk a mile in the other person’s shoes/but for the grace of God there go I. Think about how if things had gone just a little bit differently in your life, you would have turned out to be a completely different person. If you were born in ancient Roman times, could you have been cheering in the stadium as the Christians were fed to the lions? That’s why Paul says that the corrupt part of us is crucified with Christ. Paul writes: “For a person is not a Jew who is one outwardly, nor is circumcision something external and physical. Rather, a person is a Jew who is one inwardly, and circumcision is a matter of the heart, by the Spirit, not the written code. Such a person receives praise not from humans but from God” (Romans 2:28-29). Paul announces that it is the condition of one’s heart that makes him or her a true child of God. Jesus’ death awakened our hearts to renounce the fleshly in all its forms.

One of the main problems with the interpretation that Jesus died to pay a sin debt is that it doesn’t solve the principal problem of scripture—that the people had corrupted hearts: The reason for Israel’s exile is the corruption of sin within the human heart (Genesis 6:5-6; 8:21; Leviticus 26:41; Deuteronomy 30:6; Psalm 51:10; Isaiah 1:4-6; 29:13; 32:6; Jeremiah 4:4; 17:1-10; 31:31-34; Ezekiel 36:26-36). The problem isn’t that Christ must be killed because God can’t forgive sin, as the penal substitution interpretation presumes. If there is one thing that God can do in the Bible, it is forgive. Rather, God can only truly forgive if people have a change of heart. Otherwise it would be analogous to the meaninglessness of a wife continually forgiving a spouse who won’t stop cheating. The change of heart is the key component. That is why I argue for a Lukan moral influence interpretation of the cross rather than the conservative penal substitution one:

- Penal Substitution: Christ died for our sins (instead of us)

versus

- Moral Influence: Christ died for our sins (to dis-close our hidden corrupt hearts, making them conspicuous for us and hence inspiring repentance) and because of our sins (we killed him, the crowd, religious elite, and Pilate in all of us)

Penal substitution assumes that man, God’s highest creation, is essentially defective. Moral influence assumes that there is inherent goodness in man (the law written on his heart: Romans 2:15), and that it just needs to be woken up.

Jesus claims in Matthew 5:17-18 that he did not come to abolish the law, but to fulfill it (e.g., make it stricter—adultery includes a lustful eye). What does this mean? Starting at Psalm 19:7 (18 in the Septuagint) of the New English translation of the Septuagint, the Greek Old Testament that the New Testament writers were working from, the verse says:

The law of the Lord is faultless, turning souls…. Transgressions—who shall detect them? From my hidden ones clear me.

The most recent NRSVUE translation of the Hebrew text of verse 12 is similar: “But who can detect one’s own errors? Clear me from hidden faults.”

In either case the issue is the turning and converting power of the law—and the problem of hidden faults and what is to be done with them—for how can you repent of sins that you’re not aware of? This, in a nutshell, is the question that the New Testament writers are answering. The answer: The world turns on the specially chosen and favored one of God without cause, revealing to them their hidden sin nature and making repentance possible—hence the soldier at the cross in Luke says: “Truly this was an innocent man.” The idea is to see yourself in the humanity that turned on Jesus. Analogously, if you had been a citizen in ancient Rome, you probably would have enjoyed the horrors of the arena as much as any other Roman of the time.

How is this to be understood? Our earliest source, Paul, was from the birthplace of the Stoic enlightenment, and all of our Gospels were written by native Greek speakers. So apparently the Jews had become more culturally literate and inclusive with the expansion of the Roman Empire, and adopted the idea of Socrates offering a prayer of thanksgiving for the poison hemlock, as well as the idea of the impaled just man from Plato’s Republic, the most famous book in the ancient world. That is, these Greek philosophical/ethical ideas had disseminated into Jewish theological thinking. Jesus is the “truth,” in the Greek sense of “aletheia,” because he un-covers (a-letheia) hidden sin par excellence. Why? He simultaneously un-covers the essence of the law, which then inspires a “turn” or “conversion,” or better, “a change of heart.” In this way, regarding Psalm 19:7, the New King James translation is faithful to the septuagint επιστρέφων, turning or converting, inspiring a change of heart like the soldier at the cross in Mark and Luke. This is also the sense in which Jesus is sinless or unblemished (άμωμος; Psalm 19:7, LXX). Why? Jesus does not fall under the law like sinful humanity does, but re-veals it. Jesus, like God, is above the law. Jesus un-covers the essence of the law, such as in showing that adultery is not just the act; Jesus redefines it to include a lustful eye. Similarly, the essence of the law as hesed love is redefined from love of God and neighbor (widows, orphans, strangers) to selfless agape love of enemy as more important than self, or Jesus loving God and His plan in the Gethsemane prayer more than himself (“your will, not mine”). Jesus is the “agapetos” or specially beloved. Jesus on the cross as the specially favored one of God being wrongfully horrifically tortured and executed makes him the Law incarnate (personified). It is meant to inspire a change of heart, a turning or conversion, and so Christ fulfills the law with the cross not as penal substitution blood magic, but rather dis-closing or making conspicuous our hidden sinful nature to inspire repentance, since the point of the religion is God’s forgiveness is powerless if you don’t have a contrite heart, and so Jewish religious history is saturated with a forgiving God. But this wasn’t enough because they still ended up in a dystopian world under the Roman imperial thumb with a wicked Jewish elite and crowd whom Pilate would rather satisfy than bring to justice. I have received some pushback from mythicists such as Richard Carrier, who maintain a conservative penal substitution theory of the cross. This pushback is good: whatever personal pride we have in our ideas, in the name of honesty and accountability, they need to be subjected to the most severe peer evaluation possible. That said, I simply don’t see how anyone can maintain a mythical outer space Jesus interpretation of Christian origins, for the whole point is that it isn’t just what Jesus did “for” us, but what we did “to” him. I have an index of my online writings on this topic of Christian Origins here.

Psalm 19 seems to be particularly fruitful here since the New Testament writers were creatively re-writing the Old Testament, especially Psalms. Mark’s narrative of the crucifixion rewrites Psalm 22 (and Isaiah 53), for instance. In Psalm 19, verse 7 we get the idea of the law inspiring a change of heart, and in verse 12 we get the idea of a sin nature that is hidden from us and must be un-covered: we are blind to ourselves, analogous to a teenager in a toxic romantic relationship who is too close to it to see the forest for the trees. This is moral influence theology, not penal substitution blood magic.

In the section on Isaiah 53, I presented both Perriman and Roth as providing nonpenal substitution explanations for Isaiah 53. Yet, they provide very different interpretations. What I meant is that scripture sometimes serves dual functions, one of them that describes a situation presently pertinent to an author (Perriman’s reading), and another filled full of meaning in the future (Roth’s reading). We see this double technique, for instance, when Matthew appropriates Jeremiah as a prophecy (compare Matthew 2:17-18 to Jeremiah 31:15). Some view Daniel 8:17-26 this way, referring to Antiochus (the historical) and a later time (the prophetical). As I said above, as with the case of my interpretation of the Roman soldier realizing his wrongdoing with Jesus, so with Roth on Isaiah 53, the world coming to see how they wronged the Jewish people would serve as a good model for Mark regarding the world coming to see how they wronged Jesus. As will be shown below, this has to do with Satan’s control over the world ultimately being crushed under the feet of the community of the faithful, not just by the returning Jesus (Romans 16:20).

In Isaiah 53 we read:

Surely he has borne our infirmities

and carried our diseases; …

yet he bore the sin of many,

Regarding this, it’s important to note that Matthew 8:17 refers to Isaiah 53, and this is used by some to argue that Jesus bore our sins in penal substitution like he bore our sicknesses. But this interpretation makes no sense and actually shows that the exact opposite is true. Matthew 8:17 says: “This was to fulfill what had been spoken through the prophet Isaiah, ‘He took our infirmities and bore our diseases.'” Penal substitution proponents are clearly importing modern notions of the idea of “bore” here since, as Ray Fowler points out, it is obvious that Jesus did not contract leprosy when he healed the leper, transferring the disease from the sick person to Jesus’ own body. All that is being said is that Jesus removes sickness as God removes/forgives sins if you repent (compare Psalm 103:2-3). The problem was getting people to realize that they were being controlled by hidden vileness, and so became aware and wanted to repent. For instance, Ezekiel 33:11 says “I have no pleasure in the death of the wicked but that the wicked turn from their ways and live; turn back, turn back from your evil ways”—and so the moral influence of the cross came to be.

What does the scriptural coloring by the writers of Jesus’ death tell us about the historical details that we can know about his death? As the team of scholars behind the Jewish Annotated New Testament conclude, it may not be possible to locate historical material behind the heavily theologized death account imitating Isaiah 53 and Psalm 22. The above suggests that the central aspects of the religion can be completely derived from the rewriting of Hebrew scriptures. As to the source for the resurrection on the third day, Matthew prooftexts the story of Jonah being swallowed for three days in the big fish. Our earliest source for the crucifixion, Paul, understands Jesus being hung on a tree/crucified (Galatians 3:13) pointing to Deuteronomy: everyone hanged on a tree is cursed (Deuteronomy 21:23). Again, conservative evangelicals want this to mean that innocent Jesus bore our sins on the cross, but this is probably not what the passage means. Daniel R. Streett comments that:

(1) When Paul says that Jesus “became a curse,” he is saying not that God cursed Jesus but rather that Jesus condescended to the humility of the cross, was executed by his countrymen in a miscarriage of justice, and was considered by his people to be under a divine curse. (2) When Paul cites Deut 21:23, he does not intend to say that all crucified victims are de facto cursed. Rather, for Paul and his contemporaries, the charge and its validity matter. Because Jesus was innocent, he was not under the curse of Deut 21:23. Paul likely cites the passage to explain how Christ’s death brought special humiliation in the eyes of the Jewish people. (3) Finally, I have argued that Gal 3:13 is not intended to explain the mechanism of atonement, that is, some behind-the-scenes divine transaction. Rather, the text is meant to emphasize the extent of Christ’s suffering in order to redeem his people. The mechanism of redemption is more properly sought in other passages, most likely those that refer to the work of the Spirit in baptism, uniting believers to Christ in his death and resurrection. (Streett, 2015, p. 209)

Elsewhere, Streett clarifies:

Paul deliberately says that Christ “became a curse” rather than “became accursed.” His language evokes the OT covenantal threat that sinful Israel would become a curse and a byword among the nations. Paul is not, therefore, claiming that God (or the Law) cursed Christ, as is so often claimed. I adduce two key linguistic parallels from early Greek texts (Protevangelium of James and Acts of Thomas) to demonstrate that “becoming a curse” refers to a loss of social status as opposed to becoming the object of divine wrath…. Paul does not cite Deut 21:23 in order to establish that everyone who is crucified is divinely cursed. I examine early Jewish (and Christian) readings of Deut 21:23 to establish that no one believed crucifixion per se brought God’s curse on the victim. Indeed, Paul slightly but significantly modifies the wording of the verse (changing κεκατηραμένος ὑπὸ θεου to ἐπικατάρατος) to steer the audience away from this misunderstanding…. Modern readers miss the point of Paul’s statement because they approach the text with questions about the mechanics of [penal substitutionary] atonement. I urge that the passage should rather be read as a description of the status loss (“becoming a curse”) that Jesus underwent in order to redeem Israel. The passage is thus akin to Phil 2:5-9 and other texts which do not provide a theory of atonement so much as they describe the social texture of Christ’s shameful death. (Streett, 2014)

To see what is going on in the New Testament, we have to understand how the authors are playing with two levels of understanding of Yom Kippur goats sacrifices. So we have the commonplace average understanding of the sin saturated scapegoat set free corresponding with the Markan satire of the release of Barabbas, and then the true meaning of the scapegoat suffering an excess of violence as it is torn apart crashing down the cliff (so that the people can ponder the excess of violence of their sins). In this way we see with penal substitution people arbitrarily being released from their sins by the cross of Christ like the murderer of Romans Barabbas bafflingly being released on a whim by Pilate—as a caricature. Penal substitution is not the meaning of the New Testament; rather, penal substitution is what the New Testament is lampooning. Seeing the deficiency of the common penal substitution approach (and the efficacy of the deeper moral influence approach) is the key to unlocking the mystery of the Jesus cult insofar as it was the mystery faith that Mark said it was in Mark 4:11-12. The everyday Jewish tradition taught the pure goat was sacrificed for unintentional sin, and the scapegoat carried away intentional sin, and this dealt with the sin problem for one year. This is the surface meaning of the ritual that the Christians were satirizing and correcting with a deeper level moral influence sense of the cross.

With Barabbas as the personification of what Pilate (as a Roman judge) would have seen as evil in the Jews, it makes sense to initially see Jesus dying instead of Barabbas, which allows Barabbas to go free. Some interpreters thus see Barabbas as sin personified getting away: the scapegoat. Penal substitution theorists thus see Christ taking away our sins, allowing us to go free. However, there is disagreement in the literature here because the scapegoat typology fails on this reading, for there is no ritual abuse or killing of the scapegoat Barabbas. As is often the case with New Testament writing, we have a theme that is “conspicuous by its absence.” What is actually going on with the Barabbas story is that Mark is lampooning the average everyday understanding of the Jewish Yom Kippur pure goat and scapegoat ritual by showing the absurdity of it if Pilate was doing it—as though cruel Pilate would release Barabbas, a known killer of Romans, to cultivate favor with the Jewish crowd. Analogously, executing an innocent child in Africa for the crimes of a murderer in Chicago obviously makes no sense, and this crude understanding of atonement is precisely what the Christians were lampooning.

Mark satirizing the common understanding of the Yom Kippur sacrifices by showing their absurdity if Pilate were doing something analogous with Jesus and Barabbas is actually a very clear example of John Loftus’ outsider test of faith, that is, of viewing one’s own faith from the skeptical point of view of an outsider. Analogously, when a man is in a bad romantic relationship, he often can’t see the negative even though his partner’s toxicity is obvious to his friends. It would make sense that this Christian satirical writing would emerge in the first century in the Roman empire since Horatian satire had become an influential form of Roman writing just prior to Jesus’ time:

Horatian satire, named for the Roman satirist Horace (65-8 BCE), playfully criticizes some social vice through gentle, mild, and light-hearted humour. Horace (Quintus Horatius Flaccus) wrote Satires to gently ridicule the dominant opinions and “philosophical beliefs of ancient Rome and Greece” (Rankin). Rather than writing in harsh or accusing tones, he addressed issues with humor and clever mockery. Horatian satire follows this same pattern of “gently [ridiculing] the absurdities and follies of human beings” (Drury). (Wikipedia, 2023b)

The Gospels are Horatian satire mainly in the sense that they are didactic—that is, they are intended to teach. It is only under the supposition that we are reading satire that the writings can maintain their own logic—for instance, in the idea that the disciples can’t believe without seeing the risen Jesus (even though the reader is expected to believe without doing so), or in the idea that the Cana wine miracle is supposed to be the genesis for belief (even though the author is clear that it never happened, and is just a creative rewrite of the story of Elijah in 1 Kings 17:8-24 LXX per Helms, 1989, p. 86). Skeptics are correct about the absurdities in the New Testament as literal history, but often the nonsense is intentional. In fact, the great irony of the Gospels is that they are mostly presenting as history stories that are actually historical fiction that never happened and are basically made up of creative rewrites of Jewish, Greek, and Roman stories.

So, in a sense, skeptic Carrier (accepting a penal substitution/vicarious atonement interpretation) and progressive Christian McGrath (accepting a moral influence interpretation) are both right, for they really are seeing mutually exclusive elements in the same texts. Carrier is right when he sees early Christianity as another dying/rising savior cult. But when we dig deeper than Carrier and look beneath this surface, we find a deeper meaning: that it is not what Christ accomplished on the cross, but what the cross accomplished in us—by getting us to see ourselves in the indifferent-to-justice Pilate, the corrupt Jewish religious elite, the quick-to-anger crowd, and the disciples that abandoned and betrayed Jesus—that the law written on our hearts can convict and expose our hidden sinfulness and thereby act as a catalyst for repentance. Mark’s whole point is that a penal substitution cross without a contrite heart is meaningless because the person will keep on sinning: freed evil Barabbas will not change his ways just because he got released consequence-free on a technicality. John Dominic Crossan is thereby correct that the Gospels are not only history, but also parables starring Jesus, parables that we have to deconstruct to get to the hidden intent beneath their surface meaning. Sometimes they are like onions with layer under layer—for example: (1) on a surface level, Jesus dies and Barabbas goes free, (2) pointing to a commonplace surface meaning of scapegoat and penal substitution, (3) then leading to a still deeper meaning of moral influence because the ritual abuse and death of scapegoat Barabbas is “conspicuous in its absence.” It is highly technical religious and social satire masked as simple biography.

One of the biggest advances in New Testament studies in this generation has been uncovering the sophistication of the documents. We have gone from looking at them as the reports of the eyewitness testimony of peasants to so much more. There is serious intertextuality going on in them, referencing imitation of Hebrew scriptures (per Robert M. Price) and Greek/Roman literature (per Dennis R. MacDonald). It was a bit of a trick to see this sophistication in Mark because Mark’s Greek seems more crude, Matthew being written in a better Greek than Mark. In response to this Carrier made the rather brilliant observation that Mark is deliberately written in a “low Greek” analogous to how Mark Twain wrote Tom Sawyer in a “low English.” Regarding the sophistication of the New Testament and satire that I mentioned above, the New Testament writers take the term “gospel” from two main sources: (Augustan) Imperial propaganda (Mark, euaggelion) and comic “excessive sacrifice” in Aristophanes’ The Knights (Paul). As Crossan points out, in one sense the message of Peace through Victory of Caesar is being contrasted with the Peace through Justice of Jesus. In this case “gospel” means good news as propaganda about Jesus. In the second sense we have “gospel” as the satire/parody image from Aristophanes’ The Knights. In The Knights by Aristophanes (424 BCE), the comic character Paphlagon proposes an “excessive sacrifice” of a hundred heifers to Athena to celebrate good news: εὐαγγέλιον (Aristophanes, The Knights, 654-656)—as though relating to the divine is now becoming the one who cultivates the greatest bribe for the god. We see further evidence of lampooning the idea of “good news” in the Old Testament. Just as Jesus as the messenger of God is put to death for delivering/proclaiming God’s word, the New Testament writers would have been working from The Septuagint (a Greek translation of the Old Testament), which uses the word in 2 Samuel 4:10: “when a man told me, ‘Saul is dead,’ and thought he was bringing good news [εὐαγγέλια], I seized him and put him to death in Ziklag.”

The irony is that interpreting Jesus as an “excessive sacrifice” is precisely how many readers, such as Carrier, see Jesus without recognizing the parody/satire intended in the image. So, Carrier and many others say that Christian origins are about the idea that animal atonement sacrifices were insufficient to deal with sin, so a super sacrifice of God’s specially chosen one Jesus was needed once and for all: vicarious atonement/penal substitution. Once we realize that we are dealing with irony/satire here, this comic notion of Jesus as the “excessive sacrifice” can be overcome and points us to a moral influence cross: “Truly this was the son of God/an innocent man.”

The satirical reading in this example has the following three levels: first, Jesus was executed as a criminal; second, Jesus’ death paid the sin debt and atoned for humanity’s sin; and third, what Jesus’ death really did was dis-close our hidden sin nature as we see those who wronged Jesus as a mirror of ourselves and so becomes a catalyst for repentance. Like the satirical reading of the scapegoat Barabbas that I gave above, we have a clear three-part Hegelian dialectical structure (thesis-antithesis-synthesis). In the Barabbas case, we needed to dig deeper beyond the average, everyday meaning of scapegoat to see the richness of the esoteric scapegoat Christian interpretation. In The Knights, the savior or pharmakoi is the sausage-seller who undergoes a baffling transformation at the end of the story to complete his role as savior pharmakos. We can think of the transformation of Jesus from crucified criminal to risen savior. The Greek pharmakos represented a shared belief that the community was saved from disaster by the loss of certain of its members. The loss of Jesus solved the riddle of the approaching apocalypse threatening the the world because it was a path to salvation. Wikipedia explains the allegorical significance of The Knights thus:

Agoracritus—miracle-worker and/or sausage-seller: The protagonist is an ambiguous character. Within the satirical context, he is a sausage seller who must overcome self-doubts to challenge Cleon as a populist orator, yet he is a godlike, redemptive figure in the allegory. His appearance at the start of the play is not just a coincidence but a godsend (kata theon, line 147), the shameless pranks that enable him to defeat Paphlagonian were suggested to him by the goddess Athena (903), he attributes his victory to Zeus, god of the Greeks (1253), and he compares himself to a god at the end (1338). He demonstrates miraculous powers in his redemption of The People and yet it was done by boiling, a cure for meat practised by a common sausage seller. (Wikipedia, 2023a)

The conservative approach to the cross ignores that while the image of a sacrifice is used, the more common presentation is participation, which I will explain below. But in any case, as I said above with Roth, the conservative penal substitutionary view of Jesus’ sacrifice runs counter to what a sacrifice means in the Hebrew scriptures. The idea of sacrifice has to do with a relationship with God or others, not simply wiping the debt clean so that, even though you deserve to die, lucky you because God takes it out on a sheep! The image of sacrifice is used, as is that of participation.

The God of the Bible consistently forgives, and the penal substitution model where God can’t forgive flies in the face of the penitential psalms and the story of Jonah. To portray God as one who lets a criminal go free because an innocent was punished instead renders God unjust. McGrath comments:

Probably even more helpful than “Moses” was 4 Maccabees 6, which presents a martyr praying “Be merciful to your people, and let our punishment suffice for them. Make my blood their purification, and take my life in exchange for theirs” (4 Macc. 6:28-29). Clearly there were ideas that existed in the Judaism of the time that helped make sense of the death of the righteous in terms of atonement. But the New Testament does not use the language of punishment and exchange in the way 4 Maccabees does…. Paul can talk about sacrifice (and discussing what sacrifice meant in the Judaism of this time would be a subject of its own), but he prefers to use the language of participation. One died for all, so that all died (2 Corinthians 5:14). This is not only different from substitution, it is the opposite of it. Jesus is here understood not to prevent our death but to bring it about! This fits neatly within his understanding of there being two ages, with Christ having died to one and entered the resurrection age, and with Christians through their connection to him having already died to the present age and thus made able to live free from its dominion. One point is Biblical, the other is moral. First, the Bible regularly depicts God as forgiving people. If there is anything that God does consistently throughout the Bible, it is forgive. To suggest that God cannot forgive because, having said that sin would be punished, he has no choice but to punish someone, makes sense only if one has never read the penitential psalms, nor the story of Jonah. And for God to forgive, all that the Bible suggests that God has to do is forgive. The moral issue with penal substitution is closely connected with the points just mentioned. Despite the popularity of this image, to depict God as a judge who lets a criminal go free because he has punished someone else in their place is to depict God as unjust. (McGrath, 2010)

McGrath further notes: “I will not try to argue that penal and/or substitutionary imagery is never used. But the case can be made that it is neither central to the bible as a whole or to the theology of specific writers…. For instance, the Levitical background to Hebrews … helps us understand that the imagery there is of purification of the sanctuary so that God can dwell in the midst of a sinful people” (McGrath, 2010).

Scholars have long thought that Jonah was a “type” of Christ, meaning that Jesus’ story imitates/reverses the story of Jonah on many issues, and presents Jesus as greater than Jonah. Matthew writes:

38 Then some of the scribes and Pharisees said to him, “Teacher, we wish to see a sign from you.” 39 But he answered them, “An evil and adulterous generation asks for a sign, but no sign will be given to it except the sign of the prophet Jonah. 40 For just as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the sea monster, so for three days and three nights the Son of Man will be in the heart of the earth. 41 The people of Nineveh will rise up at the judgment with this generation and condemn it, because they repented at the proclamation of Jonah, and see, something greater than Jonah is here! (Matthew 12:38-41)

The difference between the people of Nineveh from the aforementioned Jonah story, and those of Jesus’ generation, is that the people weren’t repenting in Jesus’ time, and so, since the apocalypse was thought nigh, something needed to happen to save as many as possible (something needed to spur them to ask for forgiveness). We can see that imitations and reversals of the Jonah story were used to form the story of Jesus. For instance, we read from one commentator:

- Both received a mission from God to go preach. However, Jesus obeyed the Father willingly while Jonah refused at first and only obeyed reluctantly after God let him pout inside a fish.

- Both went down to Sheol for three days (Jonah 2:2). Jonah’s experience was more like extreme discomfort (in addition to it being against his will). Jesus went to his death willingly in obedience to the Father and in love for his people.

- Both were delivered from their trip down to Sheol, but Jesus was resurrected and offers that same resurrection to whoever would follow him. Jonah was merely spat out of a fish and offers a half-hearted sermon on repentance.

- Both preached a message exhorting people to repent in the face of impending judgment. Jonah preached the bare minimum and had no power to save. Jesus preached relentlessly for years…

- Both saw sinners repent and believe in God for the forgiveness of sins. Sadly, Jonah hated the Ninevites and didn’t want God to have mercy on them. Jesus, our Good Shepherd, rejoiced when sinners (especially Gentiles) repented and believed.

- In dramatic fashion, Jonah selfishly wished for death to escape his discomfort and to avoid seeing his enemies enjoy God’s mercy. Jesus, in quiet obedience, endured torture and death intended for sinners…

What is the moral of the story of Jonah? No person can sink so low as to be beyond forgiveness. As a prophet of God, Jonah had sunk about as low as he could, but God would still forgive him. Nineveh was wicked enough that God intended to destroy it, but He could still forgive them. The primary theme of the story of Jonah and the huge fish is that God’s love, grace, and compassion extend to everyone, even outsiders and oppressors. God loves all people. This story is the exact opposite of how many conservative Christians understand God: for them, God couldn’t forgive, and so Jesus needed to die. This conservative interpretation clearly makes no sense in a Jewish context.

One key to the Jonah story is that Jonah laments the successful teshuva/repentance of Nineveh, but this terrible rejection of God’s will paradoxically encourages the reader to their own teshuva/repentance, specifically to overcome the desire that we have to self-righteously criticize Jonah for being callous, clueless, etc., because we can “turn the mirror” and see Jonah’s failings in ourselves: for example, when we are angry that good things happen to bad people. For an elaboration of this point, see Rachel Rosenthal’s “Our Prophets, Ourselves: Jonah, Judgment and the Act of Repentance” (September 29, 2014).

In his fresco The Last Judgment, Michelangelo depicted Christ below Jonah (IONAS) to qualify the prophet Jonah as a "type" of Christ, Jesus being the new and greater Jonah in the same way that Matthew forms his narrative to make Jesus' story imitate and improve on the story of Moses: Jesus as the new and greater Moses.

And this is exactly the point of the Jesus story. It is seeing the vileness of those who wrongly executed Jesus present in ourselves that inspires repentance. For the first Christians, the True Holy of Holies was not the in the temple containing the Law, but storing the Law in our heart: Jesus apocalyptically thought that he was inaugurating the kingdom of God at the end of the age as he changed the hearts of men one at a time (Luke 17:21). This is done by Jesus un-covering (“a-letheia,” truth) the hidden law written on our hearts through discovering ourselves in those who tortured and killed Jesus, and letting this law shine through (Romans 2:14-15; Jeremiah 31:33-34). Why? As the saying goes, but for the grace of God any one of us could have been part of the inflamed crowd, corrupt religious elite, or indifferent to Justice Pilate, all who wrongly sent Jesus to his death. In other words, walk a mile in the other person’s shoes and see the log in your own eye before criticizing (cf. Matthew 7:5). God was willing to forgive, but this needed Jesus—not because of penal substitution, but because Jesus was the catalyst for a change of heart. Why? Jesus, the specially chosen one of God meant to restore the Davidic throne (Romans 1:3), was crucified by the world as the lowest criminal. To believe in who Jesus was (the anointed Davidic heir) meant to understand that we slapped God in the face by executing Jesus, and rejected his ultimate plan for Jesus. Of course, the real secret plan was for Jesus to die (1 Corinthians 2:7-8) to lift/clear the fog from our eyes, but in any case that was the two-fold logic of the original Christian argument.

Penal substitution simply doesn’t have any logic to it. Executing an innocent child in Africa for the crimes of a criminal in Texas simply doesn’t serve justice: God thinks that you deserve to die but, no worries, God is going to take it out on a little innocent goat. And, contra penal substitution, if repentance is acceptable for new sins, why isn’t it acceptable for old sins—why did Jesus need to die? And what has the average moral unsaved person ever done that warrants the punishment of death for their sin of lack of belief? Paul says that the gentiles who do not have the Law still show that they have the Law written on their hearts when they follow their conscience. Rather, we see in the penitential psalms that God is a God of forgiveness, not punishment. These psalms declare that God can’t resist a repentant heart. He accepts a humble and contrite heart (Psalm 51:19). In your repentant fear of Him, He wants you to be confident that “with [Him] is forgiveness” (Psalm 130:4). Of course, this is all steeped in first-century Christian apocalypticism and superstition foreign to the enlightened modern secular mind, but at least this interpretation allows us to understand the origin of Christianity in a way far more sensible/reasonable than the internally incoherent and contradictory penal substitution interpretation that makes everything about the inception of the religion look silly, ridiculous, and/or opaque.

The sacrificial imagery of the New Testament book of Hebrews has to be understood in its historical context. Jewish atonement with the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur) involved 2 goats, one that was sacrificed, and another on which sins were supposedly placed and thus was considered unsuitable for sacrifice and released into the wilderness. This second kind was the scapegoat, and was not the model for Jesus. Rather, Jesus was the sacrificial one whose death made it possible for a sinful mankind to enter into the dwelling of God like the prodigal son story, accomplishing this by (i) disclosing humanity’s hidden vileness and prompting repentance and (ii) allowing Christ who transformed from a corpse into a spirit at the resurrection, who could then be welcomed in angelic possession as “Christ in you” to possess the welcoming believer to provide strength and strategy to overcome the temptations of Satan (Christ being the overcomer of Satan par excellence). This death/resurrection sanctified, or made it possible, for sinful man to enter into God’s holy presence: reconciliation. That was the meaning of the goat’s blood of the atoning sacrifice of Yom Kippur, the other “scapegoat” being something completely different and not the role that Christ serves in the New Testament, since obviously Christ is not spared and released like the scapegoat on the traditional Day of Atonement. It is in fact conflating the sacrificial goat with the scapegoat in interpreting Christ that historically led to the penal substitution interpretive lens error. As Gordon Wenham has argued, the blood in the Day of Atonement ritual is thought to purify the most holy place from the sin and uncleanness of the people, so that God could dwell there in their midst. McGrath comments that:

None of this can be understood literally. To suggest that Jesus, after his death, somehow literally ascended to heaven with his literal blood with him and applied it to a literal tabernacle in heaven is to turn symbol into silliness.

When we ask what the sacrificial metaphor is conveying at its core level, it turns out to be the same thing that Paul emphasizes in 2 Corinthians 5 using a different metaphor, that of dying and rising to newness of life in union with Christ. In both cases, despite the different metaphors, the core message turns out to be expressed in terms of reconciliation between God and human beings, with God being the initiator in making this possible.

The biggest problem I have with a lot of contemporary Christian talk about the atonement is that it depicts God as the problem, one whose hands are tied for this or that reason, with Jesus’ death as the only way to get God to forgive us.