The Ethics We Inherit

The Cost of Allegiance

Moral Authority

The Historical Question of Jesus

Silence that Serves the Story

Letting Go of the Inheritance

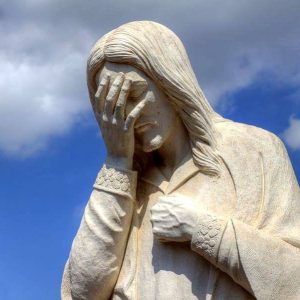

Jesus is treated as the ultimate moral guide. Reason asks if he can stand the test.

The Ethics We Inherit

You’ve heard it in courtrooms, classrooms, and campaign speeches: a quote from Jesus offered as moral truth. Yet, when these words become myth—repeated without scrutiny—they risk insulating us from deeper insight. His teachings are often revered as universal, compassionate, and wise, unquestionable even by secular thinkers who accept him as an ethical shorthand, regardless of belief in his divinity. But reverence, especially when inherited, can blur judgment. Familiarity breeds insulation.

To understand what we’re defending—or dismissing—we must examine these teachings not as sacred truths but as moral ideas subject to reasoned critique. Only by doing so can we develop ethical systems grounded in empathy, autonomy, and human connection.

The Cost of Allegiance

Many of Jesus’ teachings are praised for compassion and humility, but others raise serious ethical concerns. In Matthew 10:34-36, he declares, “Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth. I have not come to bring peace, but a sword.” He goes on to describe families torn apart by loyalty to him—”a man against his father, a daughter against her mother.” These are not metaphors for unity, but declarations of division, where loyalty to Jesus overrides even family bonds.

Even the gospels complicate the image of a purely peaceful teacher. They depict his followers carrying swords (Luke 22:36, 49) and describe his assault on the Temple, where he fashioned a whip and drove out merchants. These were not symbolic gestures but acts of force; historically implausible, too, given the Temple was likely guarded. These moments sit uneasily with the image of Jesus as a gentle moral exemplar.

In the same chapter, Jesus states, “Whoever loves father or mother more than me is not worthy of me.” This isn’t a call for empathy; it’s a demand for exclusive loyalty. Secular critics argue that such teachings prioritize obedience over autonomy and spiritual hierarchy over human connection.

The implications echo far beyond the first century. Loyalty that demands breaking natural bonds has fueled cults, sectarian movements, and political ideologies throughout history. When loyalty is elevated above relationship, division is no accident—it is the system’s very design. The cost of allegiance is not merely symbolic; it can fracture communities and families in the name of purity.

Other statements are even more extreme. “If your hand causes you to sin, cut it off” (Mark 9:43) is a hyperbolic call to self-mutilation. “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God” (Mark 10:25) suggests exclusion based on status rather than behavior.

The fig tree episode in Mark 11:12-14 also raises questions. Jesus curses a tree for not bearing fruit, even though the text notes it wasn’t the season for figs. Whether symbolic or literal, the act seems arbitrary and punitive. If this story is meant to teach judgment or authenticity, it does so through destruction aimed at something innocent.

The parables, often praised as moral lessons, also contain troubling implications. The story of the ten virgins’ rewards exclusion. The sheep are saved, the goats condemned, without nuance or appeal. These are not teachings that invite complexity. They sort, divide, and punish.

If such ideas were attributed to any other figure, they would be scrutinized. With Jesus, they are often rationalized or ignored.

These divisions, fueled by loyalty and hierarchy, prompt us to question not only the teachings themselves but also the authority behind them. What makes a figure like Jesus a moral authority? Is it his words, or the reverence we place in them?

Moral Authority

Even at the crucifixion—the moment believers call the ultimate act of sacrifice—Jesus falters. Matthew and Mark record him crying out, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” This is not the voice of serene acceptance or divine certainty; it is a cry of abandonment. If Jesus truly believed he was God’s son, destined to rise again, this complaint reveals a contradiction. Either he doubted the very truth he preached, or the story presents a figure so overwhelmed by suffering that he abandoned his own conviction. Neither scenario aligns with the image of flawless authority often portrayed in sermons and scripture.

Believers often reinterpret this cry as proof of his humanity, as if weakness itself becomes strength. But reverence does not turn collapse into clarity. If followers hold him as flawless, then his cry of abandonment cannot be excused as virtue. The figure held up as the model of faith did not transcend suffering; he broke beneath it.

When defenders gloss over the swords in Jerusalem or the violence in the Temple, they practice the same selective reading that turns a cry of despair at the cross into proof of strength.[1]

And this matters, because moral clarity does not come from being divine, it comes from being consistent. In secular ethics, authority isn’t inherited through tradition or myth; it’s earned through empathy, accountability, and coherence. Ideas are judged by their consequences: do they support autonomy, ease suffering, and respect dignity? If not, no amount of reverence can make them right.

Secular humanism, for instance, builds its framework on reason, compassion, and social responsibility. It rejects faith as a foundation for morality, insisting instead on principles that can be tested, debated, and applied across cultures. Moral authority, in this view, is not a title but a practice.

History offers reminders that revered figures are not above critique. Gandhi’s racism, Mother Teresa’s ties to dictators, Aristotle’s misogyny, each complicates their legacy. Even Abraham Lincoln, often idealized, held views we now reject. Cultural reverence does not guarantee ethical clarity.

The point is not to condemn these figures outright, but to insist that moral authority must be earned, not assumed. When we exempt Jesus from scrutiny—treating his teachings as above critique—we abandon the very standards we apply elsewhere.

And before we accept moral authority, we should ask whether the person behind it ever existed at all.

The Historical Question of Jesus

The question of Jesus’ existence is often treated as settled, but the evidence is far from conclusive. The earliest references come from Paul’s letters, which say little about his life and focus instead on his divine role. The gospel accounts, written decades later, are shaped by theological agendas and supernatural claims that undermine their reliability.

Some scholars argue Jesus may not have been a historical person at all, but a figure constructed from religious hopes, borrowed myths, and theological storytelling. Either way, what emerges is a myth that became moral authority, a story carried forward as ethical truth, even when detached from history.

Most secular historians accept that Jesus likely existed as a preacher crucified by Rome, but even they acknowledge that certainty is unattainable. The “historical Jesus,” if he lived, is buried beneath layers of myth, interpretation, and cultural projection.

But for the purposes of ethics, existence may be secondary. If the teachings attributed to Jesus are flawed, the presence or absence of a historical figure does not redeem them. A fictional character can inspire reflection, but he should not be immune to critique.

Silence that Serves the Story

One of the most striking features of the Jesus narrative is the absence of details about most of his life. After a brief story at age twelve—debating elders in the temple—the record goes quiet for nearly two decades. The gospels provide no insight into where he lived, what he did, or how his ideas evolved. This gap has inspired speculation, with theories ranging from his quiet life in Nazareth to travels across India, Egypt, or with Jewish sects like the Essenes. Yet, none of these are supported by historical evidence.

From a literary perspective, the gap is more than an inconvenience, it is a narrative device. Gaps in biography create space for projection. Myth thrives in silence, because silence cannot be contradicted. By beginning the story only when Jesus steps into public life, the gospels avoid the burden of coherence. There are no awkward years to explain, no inconsistencies to reconcile, no mundane details to weigh against the extraordinary. The story begins when useful, and ends when complete.

Whether intentional or accidental, this silence invites projection. Believers imagine hidden depth; critics question the foundation. The gaps themselves protect the story from scrutiny.

Letting Go of the Inheritance

Believing Jesus is morally superior simply because tradition says so isn’t a reasoned belief—it’s an inherited habit. And habits, however comforting, should be questioned. If we want ethical systems grounded in empathy, autonomy, and accountability, we must examine even the most familiar names.

That doesn’t mean rejecting everything associated with Jesus. It means refusing to grant moral immunity based on myth, charisma, or cultural inertia. Ideas should stand or fall on their own merit. Reverence is not a substitute for clarity.

In a secular framework, meaning is earned through coherence, not inherited through belief. If we want to live ethically, we must choose truth over comfort and reason over tradition. Reverence may feel like loyalty, but when it shields ideas from scrutiny, it becomes projection: we see what we need, not what is there. When projection fades, all that remains is silence. The myth ends. And what we choose to hear in that silence will shape the ethics we inherit, either through inherited tradition or through reasoned critique.

Note

[1] Gregory Paul, “Jesus was No Man of Peace: The Bible Says He was a Violent Coward.” Free Inquiry Vol. 35, No. 6 (October/November 2015).