(2017)

The traditional authors of the canonical Gospels—Matthew the tax collector, Mark the attendant of Peter, Luke the attendant of Paul, and John the son of Zebedee—are doubted among the majority of mainstream New Testament scholars. The public is often not familiar, however, with the complex reasons and methodology that scholars use to reach well-supported conclusions about critical issues, such as assessing the authorial traditions for ancient texts. To provide a good overview of the majority opinion about the Gospels, the Oxford Annotated Bible (a compilation of multiple scholars summarizing dominant scholarly trends for the last 150 years) states (p. 1744):

Neither the evangelists nor their first readers engaged in historical analysis. Their aim was to confirm Christian faith (Lk. 1.4; Jn. 20.31). Scholars generally agree that the Gospels were written forty to sixty years after the death of Jesus. They thus do not present eyewitness or contemporary accounts of Jesus’ life and teachings.

Unfortunately, much of the general public is not familiar with scholarly resources like the one quoted above; instead, Christian apologists often put out a lot of material, such as The Case For Christ, targeted toward lay audiences, who are not familiar with scholarly methods, in order to argue that the Gospels are the eyewitness testimonies of either Jesus’ disciples or their attendants. The mainstream scholarly view is that the Gospels are anonymous works, written in a different language than that of Jesus, in distant lands, after a substantial gap of time, by unknown persons, compiling, redacting, and inventing various traditions, in order to provide a narrative of Christianity’s central figure—Jesus Christ—to confirm the faith of their communities.

As scholarly sources like the Oxford Annotated Bible note, the Gospels are not historical works (even if they contain some historical kernels). I have discussed elsewhere some of the reasons why scholars recognize that the Gospels are not historical in their genre, purpose, or character in my article “Ancient Historical Writing Compared to the Gospels of the New Testament.” However, I will now also lay out a resource here explaining why many scholars likewise doubt the traditional authorial attributions of the Gospels.

Coming from my academic background in Classics, I have the advantage of critically studying not only the Gospels of the New Testament, but also other Greek and Latin works from the same period. In assessing the evidence for the Gospels versus other ancient texts, it is clear to me that the majority opinion in the scholarly community is correct in its assessment that the traditional authorial attributions are spurious. To illustrate this, I will compare the evidence for the Gospels’ authors with that of a secular work, namely Tacitus’ Histories. Through looking at some of the same criteria that we can use to evaluate the authorial attributions of ancient texts, I will show why scholars have many good reasons to doubt the authors of the Gospels, while being confident in the authorship of a more solid tradition, such as what we have for a historical author like Tacitus.

How do we determine the authors of ancient texts? There is no single “one-size-fits-all” methodology that can be used for every single ancient text. We literally have thousands of different texts that have come down to us from antiquity, and each has its own unique textual-critical situation. There are some general guidelines that can be applied broadly across all traditions, however, from which more specific guidelines can further be derived when assessing a particular tradition.

Scholars generally look for both internal and external evidence when determining the author of an ancient text. The internal evidence consists of whatever evidence we have within a given text. This can include the author identifying himself, mentioning persons and events that he witnessed, or using a particular writing style that we know to be used by a specific person, etc. The external evidence consists of whatever evidence we have outside a given text. This can include another author quoting the work, a later critic proposing a possible authorial attribution, or what we know about the biography of the person to whom the work is attributed, etc.

For the canonical Gospels there are a number of both internal and external reasons why scholars doubt their traditional authors—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. I shall begin by summarizing the problems with the internal evidence.

Internal Evidence

To begin with, the Gospels are all internally anonymous in that none of their authors names himself within the text. This is unlike many other ancient literary works in which the author’s name is included within the body of the text (most often in the prologue), such as Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War (1:1), which states at the beginning: “Thucydides, an Athenian, wrote the history of the war between the Peloponnesians and the Athenians, as they fought against each other.” The historians Herodotus (1:1), Dionysius of Halicarnassus (1.8.4), and Josephus (BJ 1.3) all likewise include their names in prologues. Sometimes an author’s name can also appear later in the text. In his Life of Otho (10.1), for example, the biographer Suetonius Tranquillus refers to “my father, Suetonius Laetus,” which thus identifies his own family name.

It should be noted that the Gospels’ internal anonymity also stands in contrast with most of the other books in the New Testament, which provide the names of their authors (or, at least, their putative authors) within the text itself. As Armin Baum (“The Anonymity of the New Testament History Books,” p. 121) explains:

While most New Testament letters bear the names of their (purported) authors (James, Jude, Paul, Peter, or at least “the Elder”) the authors of the historical books [the Gospels and Acts] do not reveal their names. The superscriptions that include personal names (“Gospel according to Matthew” etc.) are clearly secondary.

Two exceptions are the Book of Hebrews and 1 John, which are anonymous texts, later attributed to the apostle Paul and John the son of Zebedee, respectively. Modern scholars, however, also doubt both of these later attributions. As the Oxford Annotated Bible (p. 2103) explains about the authorship of Hebrews:

Despite the traditional attribution to Paul … [t]here is not sufficient evidence to identify any person named in the New Testament as the author; thus it is held to be anonymous.

And about the authorship of 1 John (p. 2137):

The anonymous voice of 1 John was identified with the author of the Fourth Gospel by the end of the second century CE … Since the Gospel was attributed to the apostle John, the son of Zebedee, early Christians concluded that he had composed 1 John near the end of his long life … Modern scholars have a more complex view of the development of the Johannine community and its writings. The opening verses of 1 John employ a first person plural “we” … That “we” probably refers to a circle of teachers faithful to the apostolic testimony of the Beloved Disciple and evangelist. A prominent member of that group composed this introduction.

As such, it is not unusual for scholars to doubt the traditional authorship of the Gospels, considering that the authorial attributions of the other anonymous books in the New Testament are also in considerable dispute.

The internal anonymity of the Gospels is even acknowledged by many apologists and conservative scholars, such as Craig Blomberg, who states in The Case for Christ (p. 22): “It’s important to acknowledge that strictly speaking, the gospels are anonymous.” So, immediately one type of evidence that we lack for the Gospels is their authors identifying themselves within the body of the text. This need not be an immediate death blow, however, since ancient authors did not always name themselves within the bodies of their texts. I have specifically chosen to compare the Gospels’ authorial traditions with that of Tacitus’ Histories, since Tacitus likewise does not name himself within his historical works. If the author does not name himself within the text, there are other types of evidence that can be looked at.

First, even if the body of a text does not name its author, there is often still a name and title affixed to a text in our surviving manuscript traditions. These titles normally identify the traditional author. The standard naming convention for ancient literary works was to place the author’s name in the genitive case (indicating personal possession), followed by the title of the work. Classical scholar Clarence Mendell in Tacitus: The Man And His Work (pp. 295-296) notes that our earliest manuscript copies of both Tacitus’ Annals and Histories identify Tacitus as the author by placing his name in the genitive (Corneli Taciti), followed by the manuscript titles.[1] For the Histories (as well as books 11-16 of the Annals), in particular, Mendell (p. 345) also notes that many of the later manuscripts have the title Cor. Taciti Libri (“The Books of Cornelius Tacitus”). This naming convention is important, since it specifically identifies Tacitus as the author of the work. An attribution may still be doubted for any number of reasons, but it is important that there at least be a clear attribution.

Here, we already have a problem with the traditional authors of the Gospels. The titles that come down in our manuscripts of the Gospels do not even explicitly claim Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John as their authors. Instead, the Gospels have an abnormal title convention, where they instead use the Greek preposition κατα, meaning “according to” or “handed down from,” followed by the traditional names. For example, the Gospel of Matthew is titled ευαγγελιον κατα Μαθθαιον (“The Gospel according to Matthew”). This is problematic, from the beginning, in that the earliest title traditions already use a grammatical construction to distance themselves from an explicit claim to authorship. Instead, the titles operate more as placeholder names, where the Gospels have been “handed down” by church traditions affixed to names of figures in the early church, rather than the author being clearly identified.[2] In the case of Tacitus, none of our surviving titles or references says that the Annals or Histories were written “according to Tacitus” or “handed down from Tacitus.” Instead, we have a clear attribution to Tacitus in one case, and only ambivalent attributions in the titles of the Gospels.[3]

Furthermore, it is not even clear that the Gospels’ abnormal titles were originally placed in the first manuscript copies. We do not have the autograph manuscript (i.e., the first manuscript written) of any literary work from antiquity, but for the Gospels, the earliest manuscripts that we possess have grammatical variations in their title conventions. This divergence in form suggests that, unlike the body of the text (which mostly remains consistent in transmission), the Gospels’ manuscript titles were not a fixed or original feature of the text itself.[4] As textual criticism expert Bart Ehrman (Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium, pp. 249-250) points out:

Because our surviving Greek manuscripts provide such a wide variety of (different) titles for the Gospels, textual scholars have long realized that their familiar names do not go back to a single ‘original’ title, but were added by later scribes.

The specific wording of the Gospel titles also suggests that the portion bearing their names was a later addition. The κατα (“according to”) preposition supplements the word ευαγγελιον (“gospel”). This word for “gospel” was implicitly connected with Jesus, meaning that the full title was το ευαγγελιον Ιησου Χριστου (“The Gospel of Jesus Christ”), with the additional preposition κατα (“according to”) used to distinguish specific gospels by their individual names. Before there were multiple gospels written, however, this addition would have been unnecessary. In fact, many scholars argue that the opening line of the Gospel of Mark (1:1) probably functioned as the original title of the text:

The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ…

This original title of Mark can be compared with those of other ancient texts in which the opening lines served as titles. Herodotus’ Histories (1.1), for example, begins with the following line which probably served as the title of the text:

This is the exposition of the history of Herodotus…

A major difference between the Gospel of Mark and Herodotus’ Histories, however, is that opening line of Mark does not name the text’s author, but instead attributes the gospel to Jesus Christ. This title became insufficient, however, when there were multiple “gospels of Jesus” in circulation, and so, the additional κατα (“according to”) formula was used to distinguish specific gospels by their individual names. This circumstance, however, suggests that the names themselves were a later addition, as there would have been no need for such a distinction before multiple gospels were in circulation.

So, in addition to the problem that the Gospel titles do not even explicitly claim authors, we likewise have strong reason to suspect that these named titles were not even affixed to the first manuscript copies. This absence is important, since (as will be discussed under the “External Evidence” section below) the first church fathers who alluded to or quoted passages from the Gospels, for nearly a century after their composition, did so anonymously. Since these sources do not refer to the Gospels by their traditional names, this adds further evidence that the titles bearing those names were not added until a later period (probably in the latter half of the 2nd century CE), after these church fathers were writing.[5] And, if the manuscript titles were added later, and the Gospels themselves were quoted without names, this means that there is no evidence that the Gospels were referred to by their traditional names during the earliest period of their circulation. Instead, the Gospels would have more likely circulated anonymously.

As discussed above, Tacitus’ name is not affixed to his Histories using an “according to” formula (which in Latin would have been secundum Tacitum). Instead, Tacitus’ name was attached to the title in the genitive (“The Histories of Tacitus”). This kind of construction is not likely as a secondary addition, since the name Tacitus is not being used to distinguish multiple versions of a text, but is rather being used to indicate Tacitus’ personal possession of the work itself. That being said, there are substantial variations between the titles of Tacitus’ earliest manuscript copies. As Mendell (p. 345) explains, “the manuscript tradition of the Major Works [the Annals and Histories] is not consistent in the matter of title.” These variations report different names for the historical works that are attached to Tacitus’ name. The manuscripts of the Histories, for example, can also include the terms res gestae, historia Augustae, and acta diurna within the titles, in addition to historiae.

These title variations appear much later than those of the Gospels (which appear only a couple centuries after their composition), however, since we do not possess manuscripts of Tacitus’ historical works until several centuries after he composed, during the medieval period. (For an explanation of why the survival of fewer and later manuscript copies has no bearing upon the historical value of Tacitus versus the Gospels, see here.) Due to the negligence among medieval scribes in preserving manuscript copies of old Pagan literary works, both Tacitus’ Annals and Histories also contain large portions of missing material. Since these are far later copies, with large lacunas in the manuscripts, the title variations may have crept in later in the tradition.[6]

Nevertheless, Mendell (p. 345) notes that we have strong contemporary evidence to suggest that the title “Historiae” was originally associated with Tacitus’ Histories:

Pliny clearly referred to the work in which Tacitus was engaged as Historiae: Auguror nec me fallit augurium Historias tuas immortales futuras [“I predict, and my prediction does not deceive me, that your Histories will be immortal”] (Ep. 7.33.1). It is not clear whether the term was a specific one or simply referred to the general category of historical writing. The material to which Pliny refers, the eruption of Vesuvius, would have been in the Histories. Tertullian (Apologeticus Adversus Gentes 16, and Ad nationes 1.11 cites the Histories, using the term as a title: in quinta Historiarum [“Tacitus in the fifth book of his Histories“]. It should be noted that this reference is to the ‘separate’ tradition, not to the thirty-book tradition, so that Historiae are the Histories as we name them now.

The evidence for the original title of the Histories is not fully conclusive, but what is noteworthy is that Pliny the Younger (a contemporary) writes directly to Tacitus and says that he is writing a “Historiae,” and Tertullian, the next author to explicitly cite passages in the Histories, refers to the work by that title.

For the purposes of authorship, however, the name of the work itself need not fully concern us. The evidence is certain in the case of Tacitus that the earliest manuscript tradition of his Histories clearly identifies him as the personal author. This manuscript tradition, though late in the process of textual transition, is corroborated by Pliny (a contemporary of Tacitus), who states that Tacitus himself was authoring a historical work about the same period and events covered in the Histories. This evidence is important, because it shows that Tacitus was known as the author of this historical work from the beginning of its transmission. And, although Pliny was writing while the work was still being composed (and thus does not cite passages from the text), the first source to cite passages from the Histories after it was published, Tertullian, clearly refers to Tacitus as the known author of the text. In Tacitus’ case, therefore, we have a clear claim to authorship, which dates back to the beginning of the tradition.

In the case of the Gospels, the first church fathers who allude to or quote the texts for nearly a century after their composition do so anonymously. Since the Gospels’ manuscript titles were likewise probably later additions (most likely after the mid-2nd century CE), this means that there is no evidence that the Gospels were referred to by their traditional names from the beginning of the tradition. Instead, these names only appear later in the tradition, which is the evidence to be expected if the Gospels first circulated anonymously, and were only given their authorial attributions in a subsequent period. Likewise, even when the later titles were added, the attributions were listed only as “according to” the names affixed to each text, which still entails considerable ambiguity about their authors.[7]

Beyond the titles, we can look within the body of a text to see if the author himself reveals any clues either directly or indirectly about his identity. For Tacitus, while the author does not explicitly name himself, he does discuss his relation to the events that he is describing in the Histories (1:1):

I myself was not acquainted with Galba, Otho, or Vitellius, either by profit or injury. I would not deny that my rank was first elevated by Vespasian, then raised by Titus, and still further increased by Domitian; but to those who profess unaltered truth, it is requisite to speak neither with partisanship nor prejudice.[8]

Here, while he does not name himself, the author of the Histories reveals himself to be a Roman politician during the Flavian Dynasty, which he specifies to be the period that he will write about. This matches the biographical information that we have of Tacitus outside of the Histories. For example, we know outside the text that Tacitus was writing a historical work about the Flavian period, since we have letters from Pliny the Younger (6.16; 6.20) written to Tacitus, where he responds to Tacitus’ request for information about the eruption of Mount Vesuvius (which Tacitus also alludes to Histories 1.2). Pliny’s letters also refer to Tacitus’ career as a statesman, such as when he gave the funeral oration for the Roman general Verginius Rufus (2.1). So we know from outside the Histories that Tacitus was a Roman politician writing a history about the Flavian era. This outside information is corroborated exactly by the evidence within the text. Thus, we have good reason to suspect that the author of the Histories is Tacitus, as the internal evidence strongly coincides with this tradition.

This kind of first person interjection from the author, described above, where Tacitus mentions his own relation to events within the narrative, stands in stark contrast with the anonymous style of narration in the Gospels. Although Tacitus does not overtly name himself in his historical works, he still uses the first person to discuss biographical details about himself. The gospels Matthew and Mark, in contrast, do not even use the first person, spoken by the author, anywhere in the text! Instead, both narratives are told in the third person, from an external narrator. This style of narration casts doubt on whether either author is relating personal experiences. As Irene de Jong (Narratology & Classics: A Practical Guide, p. 17) explains:

It is an important principle of narratology that the narrator cannot automatically be equated with the author; rather, it is a creation of the author, like the characters.

The narrators of both Matthew and Mark describe the events in their texts from an outside point of view. This is a subtle aspect of both texts, but it is a very important consideration for why scholars describe them as “anonymous.” Neither narrative is an overt recollection of personal experiences, but rather focuses solely on the subject—Jesus Christ—with the author fading into the background, making it unclear whether the author has any personal relation to events set within the narrative at all.

The author of Luke-Acts only uses the first person singular in the prologues of his works (Luke 1:3; Acts 1:1), without describing any biographical details about himself, and it is doubtful that the use of the first person plural, scattered throughout the “we” passages in Acts (16:10-17; 20:5-15; 21:1-18; 27:1-28:16), reflects the personal experiences of the author (discussed further by William Campbell under the “External Evidence” section below). John is thus the only gospel to include any kind of eyewitness construction, through the mention of an anonymous “beloved disciple” (John 21:24); however, modern scholars doubt that this “beloved disciple” was the actual author of John (see endnotes 31 and 32 below), and the character’s complete anonymity fails to explicitly connect it with the experiences of any known figure within the narrative.

Another piece of internal evidence that scholars look at is the linguistic rigor and complexity of a text. Based on the writing itself, we can tell that a certain level of education was required to author it. On this point, it is worth noting that Tacitus, as an educated Roman politician, would have had all of the literary, rhetorical, and compositional training needed to author a complex work of prose, such as his Histories. That is to say, from what we know of the Tacitus’ background, he belonged to the demographic of people whom we would expect to write complex Latin Histories.

As we will see for the Gospels’ authors, we have little reason to suspect, at least in the case of Matthew and John, that their traditional authors would have even been able to write a complex narrative in Greek prose. According the estimates of William Harris in his classic study Ancient Literacy (p. 22), “The likely overall illiteracy of the Roman Empire under the principate is almost certain to have been above 90%.” Of the remaining tenth, only a few could read and write well, and even a smaller fraction could author complex prose works like the Gospels.[9]

Immediately, the language and style of the Gospel of John contradicts the traditional attribution of the text to John the son of Zebedee. We know from internal evidence, based on its complex Greek composition, that the author of this gospel had advanced literacy and training in the Greek language. Yet, from what we know of the biography of John the son of Zebedee, it would rather improbable that he could author such a text. John was a poor, rural peasant from Galilee, who spoke Aramaic. In an ancient world where literary training was largely restricted to a small fraction of rich, educated elite, we have little reason to suspect that an Aramaic-speaking Galilean peasant could author a complex Greek gospel. Furthermore, in Acts 4:13, John is even explicitly identified as being αγραμματος (“illiterate”), which shows that even evidence within the New Testament itself would not identify such a figure as an author.[10]

Likewise, the internal evidence of the Gospel of Matthew contradicts the traditional attribution to Matthew (or Levi) the tax collector. While tax collectors had basic training in accounting, the Gospel of Matthew is written in a complex narrative of Greek prose that shows extensive familiarity with Jewish scripture and teachings. However, tax collectors were regarded by educated Jews as a sinful, “pro-Roman” class (as noted by J. R. Donahue in “Tax Collectors and Sinners: An Attempt at Identification“), who were alienated from their religious community, as is evidenced by the Pharisees accusations against Jesus in Mark 2:15-17, Matthew 9:10-13, and Luke 5:29-31 for associating “with tax collectors and sinners” (μετα των τελωνων και αμαρτωλων). Regarding the authorship of the Gospel of Matthew, scholar Barbara Reid (The Gospel According to Matthew, pp. 5-6) explains, “The author had extensive knowledge of the Hebrew Scriptures and a keen concern for Jewish observance and the role of the Law … It is doubtful that a tax collector would have the kind of religious and literary education needed to produce this Gospel.” For a further analysis of why Matthew the tax collector would have probably lacked the religious and literary education needed to author the gospel attributed to his name, see my essay “Matthew the τελωνης (“Toll Collector”) and the Authorship of the First Gospel.”

We have no such problem, however, in the case of Tacitus. As an educated Roman senator, who belonged to a small social class of people known to author Latin Histories, Tacitus is the exact sort of person that we would expect to author a work like the Histories, whereas we would have no strong reason to believe that an illiterate peasant, like John, or a mere tax collector, like Matthew, would have been able to author the Greek gospels that are attributed to them.[11]

Furthermore, the sources used within a text can often betray clues about its author. In the case of the Gospels, we know that they are all interdependent upon each other for their information.[12] Matthew borrows from as much as 80% of the verses in the Gospel of Mark, and Luke borrows from 65%. And while John does not follow the ipsissima verba of the earlier gospels, its author was still probably aware of the earlier narratives (as shown by scholar Louis Ruprecht in This Tragic Gospel).

Once more for the Gospel of Matthew, the internal evidence contradicts the traditional authorial attribution. The disciple Matthew was allegedly an eyewitness of Jesus. John Mark, on the other hand, who is the traditional author of the Gospel of Mark, was neither an eyewitness of Jesus nor a disciple, but merely a later attendant of Peter. And yet the author of Matthew copies from 80% of the verses in Mark. Why would Matthew, an alleged eyewitness, need to borrow from as much as 80% of the material of Mark, a non-eyewitness? As the Oxford Annotated Bible (p. 1746) concludes, “[T]he fact that the evangelist was so reliant upon Mark and a collection of Jesus’ sayings (“Q”) seems to point to a later, unknown, author.”

Apologists will often posit dubious assumptions to explain away this problem with the disciple Matthew, an alleged eyewitness, borrowing the bulk of his text from a non-eyewitness. For example, Blomberg in The Case for Christ (p. 28) speculates:

It only makes sense if Mark was indeed basing his account on the recollections of the eyewitness Peter … it would make sense for Matthew, even though he was an eyewitness, to rely on Peter’s version of events as transmitted through Mark.

To begin with, nowhere in the Gospel of Mark does the author ever claim that he based his account on the recollections of Peter (Blomberg is splicing this detail with a later dubious claim by the church father Papias, to be discussed below). The author of Mark never names any eyewitness from whom he gathered information.

But what is further problematic for Blomberg’s assumption is that his description of how the author of Matthew used Mark is way off. The author of Matthew does not “rely” on Mark rather than redact Mark to change important details from the earlier gospel. As scholar J. C. Fenton (The Gospel of St. Matthew, p. 12) explains, “the changes which he makes in Mark’s way of telling the story are not those corrections which an eyewitness might make in the account of one who was not an eyewitness.” Instead, many of the changes that Matthew makes to Mark are to correct misunderstandings of the Jewish scriptures. For example, in Mark 1:2-3 the author misquotes the Book of Isaiah by including a verse from Malachi 3:1 in addition to Isaiah 40:3. As scholar Pheme Perkins (Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels, p. 177) points out, “Matthew corrects the citation” in Matthew 3:3 by removing the verse from Malachi and only including Isaiah 40:3.

There are also other instances where Matthew adds Jewish elements that Mark overlooks. For example:

- Mark 9:4 names Elijah before Moses. Instead, Matthew 17:3 puts Moses before Elijah, since Moses is a more important figure to Jews than Elijah.

- Mark 11:10 refers to the kingdom of “our father” David. Ancient Jews would not have referred to “our father” David, however, since the father of the nation was Abraham, or possibly Jacob, who was renamed Israel. As such, not all Jews were sons of David. Instead, Matthew 21:9 does not refer to “our father” David.

These are subtle differences, but what they demonstrate is that the author of Matthew was not “relying” on Peter via Mark, but was redacting the earlier gospel to make it more consistent with Jewish scripture and teachings! This makes no sense at all for Blomberg’s hypothesis. Matthew is described as a tax collector (a profession that made one a social outcast from the Jewish religious community). Peter, in contrast, is described as a Galilean Jew who was Jesus’ chief disciple. Why would Matthew redact the recollections of Peter via the writings of his attendant in order to make them more consistent with Jewish scripture and teachings?

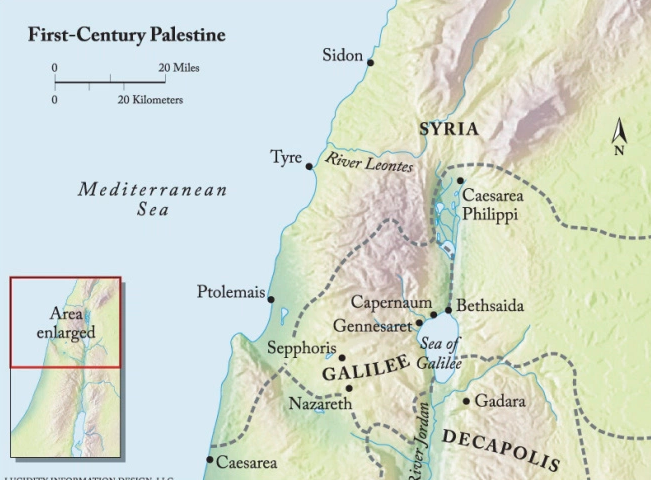

Instead, many scholars argue that the anonymous author of Mark was more likely an unknown Gentile living in the Jewish Diaspora outside of Palestine. This is strengthened by the fact that Mark uses Greek translations to quote from the Old Testament. Likewise, the author is unaware of many features of Palestinian geography. Just for one brief example: in Mark 7:31 Jesus is described as having traveled out of Tyre through Sidon (north of Tyre) to the Sea of Galilee (south of Tyre). In the words of scholar Hugh Anderson in The Gospel of Mark (p. 192), this would be like “travelling from Cornwall to London by way of Manchester.” These discrepancies make little sense if the author of Mark was a traveling attendant of Peter, an Aramaic-speaking native of Galilee.[13]

Instead, scholars recognize that the author of Matthew was actually an ethnic Jew (probably a Greek-speaking and educated Jew, who was living in Antioch). As someone more familiar with Jewish teachings, he redacted Mark to correct many of the non-Jewish elements in the earlier gospel. This again makes little sense if the author of Matthew was actually Matthew the tax collector, whose profession would have ostracized him from the Jewish community. Instead, scholars recognize that the later authorial attributions of both of these works are most likely wrong.[14] In fact, even conservative New Testament scholars like Bruce Metzger (The New Testament, p. 97) have agreed:

In the case of the first Gospel, the apostle Matthew can scarcely be the final author; for why should one who presumably had been an eyewitness of much that he records depend … upon the account given by Mark, who had not been an eyewitness?

And Christian scholar Raymond Brown (An Introduction to the New Testament, pp. 159-160) likewise acknowledges:

That the author of the Greek Gospel was John Mark, a (presumably Aramaic-speaking) Jew of Jerusalem who had early become a Christian, is hard to reconcile with the impression that it does not seem to be a translation from Aramaic, that it seems to depend on oral traditions (and perhaps already shaped sources) received in Greek, and that it seems confused about Palestinian geography.

The way that the Gospel of Luke uses Mark as a source likewise casts doubt on the tradition that John Mark, the attendant of Peter, was the original author of the text. As discussed above, the author of Luke borrows from as much as 65% of the verses in Mark. This is all very interesting, since the author of Luke is likewise the author of Acts, and John Mark, the attendant of Peter, has an appearance in Acts (12:12). This means that the author of Luke-Acts includes within his later narrative the alleged author of an earlier gospel, from which he has even borrowed a substantial amount of his material. Yet, never once does the author of Luke-Acts identify this man as one of his major sources! As Randel Helms points out in Who Wrote the Gospels? (p. 2):

So the author of Luke-Acts not only knew about a John Mark of Jerusalem, the personal associate of Peter and Paul, but also possessed a copy of what we call the Gospel of Mark, copying some three hundred of its verses into the Gospel of Luke, and never once thought to link the two—John Mark and the Gospel of Mark—together! The reason is simple: the connecting of the anonymous Gospel of Mark with John Mark of Jerusalem is a second-century guess, on that had not been made in Luke’s time.

Apologists here will merely try to dismiss this point as being an argument from silence. But again, as in the case of Matthew, the way that the author of Luke uses Mark strongly suggests that he was not “relying” on the recollections of Peter via his attendant, as Blomberg suggests, but was redacting an earlier anonymous narrative. For example, Bart Ehrman in Jesus Interrupted (pp. 64-70) discusses how the author of Luke makes changes to many of the details of the passion scene in Mark. In the Markan Passion, Jesus is depicted in despair and agony, whereas in the Lukan Passion, key details are changed to instead depict Jesus as calm and tranquil during his crucifixion. For example, Jesus’ last words are altered from a despairing statement in Mark 15:33-37 to a more tranquil one in Luke 23:44-46. But why would Luke—the mere Gentile attendant of Paul—redact and change the recollections of Peter—the chief disciple of Jesus—about the passion, crucifixion, and death of Jesus? The reason why is that the author of Luke most likely did not believe that Mark was based on the teachings of Peter. Instead, the anonymous author of Luke redacted and changed Mark, which was written by another anonymous author, to suite his own theological and narrative purposes.[15]

A final note about the Gospels borrowing material from each other is that such works, which are not entirely original in their composition, but are largely redactions of earlier traditions, generally lack authorial personality. We saw above that Tacitus (Histories 1:1) discusses his relations with the Roman emperors during the Roman civil war of 69 CE and the Flavian Dynasty, which is the period that his Histories is written about. The Gospels, in contrast, are not written to tell the recollections of any one person, let alone an eyewitness.[16] Instead, the Gospels are highly anonymous, not only in not naming their authors, but in writing in a collective, revisionist manner. New Testament expert Bart Ehrman (Forged, p. 224) explains that the general anonymity of the Gospels, in part, derives from the anonymous narrative structures of Old Testament texts, which served as their model of inspiration:

In all four Gospels, the story of Jesus is presented as a continuation of the history of the people of God as narrated in the Jewish Bible. The portions of the Old Testament that relate to the history of Israel after the death of Moses are found in the books of Joshua, Judges, 1 and 2 Samuel, and 1 and 2 Kings. All of these books are written anonymously … [T]he message of the Gospels … is portrayed … as continuous with the anonymously written history of Israel as laid out in the Old Testament Scriptures.

The authors of the Gospels were thus more concerned with gathering a collection of their communities’ teachings and organizing them into a cohesive narrative, similar to the anonymous, third person narratives found in the Old Testament. As Armin Baum (“The Anonymity of the New Testament History Books,” p. 142) explains, “The anonymity of the Gospels is thus rooted in a deep conviction concerning the ultimate priority of their subject matter.” This is not at all the case for Tacitus. We might be suspicious of the authorial attribution (at least to the extent that the Histories can be considered Tacitus’ own version of events), if Tacitus had merely copied from 80% of the material of an earlier author (as the Gospel of Matthew did) in order to write a highly anonymous narrative. Instead, Tacitus wrote in a unique Latin style that distinguished him as an individual, personal author, and he likewise comments on the events within his narrative from his own personal point of view.

We have seen above that the internal evidence does not support Matthew, Mark, or John as the authors of the gospels attributed to them. What about Luke? The Gospel of Luke and Acts are attributed to Luke, the traveling attendant of Paul. This is all very interesting, since we possess 7 undisputed epistles of the apostle Paul in the New Testament (6 of the traditional letters of Paul—Ephesians, Colossians, 2 Thessalonians, 1 and 2 Timothy, and Titus—are of disputed authorship and are possibly forgeries, as explained by Ehrman in Forged: Writing in the Name of God.) If Luke was Paul’s attendant, then corroborating details between Acts and the Pauline epistles may support the claim that Luke authored Acts; however, scholars often find the opposite to be the case.[17] To name a few discrepancies:

- In Acts 9:26-28, Paul travels from Damascus to Jerusalem only “days” (Acts 9:19; 9:23) after his conversion in Acts 9:3-8, where Barnabas introduces him to the other apostles. However, in his own writings (Galatians 1:16-19), Paul states that he “did not consult any human of flesh and blood” after his conversion (despite consulting Ananias and preaching in the synagogues of Damascus after his conversion in Acts 9:17-22), but instead traveled into Arabia (which Acts makes no mention of), and did not travel to Jerusalem until “three years” after the event, where he only met Peter and James.[18]

- In Acts 16:1-3, Paul has a disciple named Timothy, who was born from a Greek father, be circumcised “due to the Jews who lived in that area.” However, this goes against Paul’s own deceleration (Galatians 2:7) “of ministering the gospel to the uncircumcised.” Likewise, in Galatians 2:1-3, Paul brings another Gentile disciple, Titus, to the Jewish community in Jerusalem, but particularly insists that Titus not be circumcised.[19] Likewise, in 1 Corinthians 7:20, Paul states regarding circumcision, “Each should remain in the condition in which they were called to God.”

- In Galatians 2:6, Paul makes it clear that his authority is equal to the original apostles, stating, “Of whatever sort they were makes no difference to me; God does not show partiality—their opinions added nothing to my message.” However, in Acts 13:31, Paul grants higher authority to those who originally “witnessed” Jesus. Likewise, Acts 1:21 restricts the status of “apostle” to those who had originally been with Jesus during his ministry, despite Paul’s repeated insistence that he was an apostle within his own letters (1 Corinthians 9:1-2).

In light of these and other discrepancies between Paul’s own recollections and how he is depicted in Acts, many scholars agree that the author of Luke-Acts was probably not an attendant of Paul (the speculation that he was is based largely on the ambiguous use of the first person plural in a few sections of Acts, to be addressed below). Nevertheless, the author of Luke-Acts clearly had a strong interest in Paul. However, the Oxford Annotated Bible (p. 1919) points out that the author “was probably someone from the Pauline mission area who, a generation or so after Paul, addressed issues facing Christians who found themselves in circumstances different from those addressed by Paul himself.” Hence, we once more have an anonymous author who was distanced from the various traditions and stories that he later compiled as a non-eyewitness.

The same problem of discrepancies between a text and outside epistolary evidence does not exist in the case of Tacitus. For example, we have Pliny the Younger’s letters (6.16; 6.20) written to Tacitus about the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in Campania. This outside evidence is corroborated within the text, when Tacitus mentions the burial of cities in Campania in the praefatio of his Histories (1.2), as well as when Tacitus mentions the volcanic eruption itself in his Annals (4.6). That Tacitus alludes to the volcanic eruption in the introduction to his Histories shows that he used Pliny’s account when describing the disaster more fully later in his narrative (although these later books did not survive the bottleneck of texts lost during the Middle Ages). Thus, in the case of Tacitus, we have harmony between outside epistolary evidence and the internal evidence of the text, whereas in the case of the Gospel of Luke, we have discrepancies between Paul’s letters, showing that the author was probably not a companion of Paul.

So far I have addressed the internal evidence for the authorship of Tacitus’ Histories and the Gospels. As has been shown, Tacitus has passed the criteria with flying colors, while all of the Gospels have had multiple internal problems. However, there are likewise external reasons to doubt the traditional authors of the Gospels.

External Evidence

In terms of external evidence for the authorship of Tacitus’ Histories, we have Pliny the Younger (a contemporary) writing directly to Tacitus while he was authoring a work that Pliny calls a “Historiae.” This historical work that Pliny describes was further identified as the Histories that we possess today by Tertullian (c. 200 CE), who was the next author to directly refer to it. Tertullian names Tacitus as the author in Apologeticus Adversus Gentes 16, and refers to the “fifth book of his Histories” (quinta Historiarum). Regarding subsequent citations of Tacitus’ historical works, Mendell (Tacitus: The Man And His Work, p. 225) explains:

Tacitus is mentioned or quoted in each century down to and including the sixth.

Thus, Tacitus was identified as the author of his Histories from the beginning of the tradition, rather than being speculated to be the author later in the tradition. This is very strong external evidence. We have precisely the opposite situation in the case of the Gospels. As New Testament expert Bart Ehrman (Forged, p. 225) explains:

The anonymity of the Gospel writers was respected for decades. When the Gospels of the New Testament are alluded to and quoted by authors of the early second century, they are never entitled, never named. Even Justin Martyr, writing around 150-60 CE, quotes verses from the Gospels, but does not indicate what the Gospels were named. For Justin, these books are simply known, collectively, as the “Memoirs of the Apostles.”

Below are the first references and quotations of the Gospels among external source, which treat them anonymously for some decades after their composition:

Ignatius (c. 105-115 CE) appears to quote phrases from Matthew (see here), and to allude to the star over Bethlehem (Matthew 2:1-12) in his Letter to the Ephesians (19:2); however, Ignatius does not attribute any of this material to the disciple Matthew nor does he refer to a “Gospel according to Matthew.” Polycarp (c. 110-140 CE) likewise appears to quote multiple phrases and verses from Matthew, Mark, and Luke (see here), and yet he neither attributes any of this material to their traditional authors nor refers to their traditional titles. There is scholarly dispute, however, as to whether Ignatius and Polycarp are quoting written texts, or instead interacting with oral traditions. As such, it is uncertain whether these two authors are directly referencing the Gospels that we possess today.

A stronger case can be made that the Epistle of Barnabas (80-120 CE) quotes Matthew (22:14), particularly because the epistle says “it is written” (4:14), when referring to the verse “many are invited, but few are chosen”; and yet, the Epistle of Barnabas does not attribute this verse to a text written by the disciple Matthew. What is further worth noting is that the Epistle of Barnabas (4:3) also refers to the Book of Enoch, and states “as Enoch saith,” showing that the epistle refers to traditional authorship elsewhere, when it was known.

Even more important, however, is when the Didache (c. 50-120 CE) directly quotes the Lord’s prayer (8:3-11), which is written in Matthew 6:9-13. This quotation is important, because the Didache attributes these verses to “His (Jesus’) Gospel” (ο κυριος εν τω ευαγγελιω αυτου) without referring to a “Gospel according to Matthew.” What the Didache is probably referring to, therefore, is the original title of the Gospels, before they were attributed to their traditional names. As discussed under the “Internal Evidence” section above, the Gospels were most likely originally referred to under the title το ευαγγελιον Ιησου Χριστου (“The Gospel of Jesus Christ”); however, when later there were multiple gospels in circulation, the construction κατα (“according to”) was added, in order to distinguish individual gospels by their designated names. The Didache likely preserves, therefore, a trace of their original titles, which were anonymous.

Justin Martyr (c. 150-160 CE) later makes explicit references and quotations of the Gospels (see here), but ascribes them under the collective title of “Memoirs of the Apostles,” without making any explicit mention of their traditional names. Finally, Irenaeus (c. 175-185 CE) refers to the Gospels by their traditional names in the late-2nd century (see here). As such, there is a clear development in which the Gospels were first referred to anonymously by external sources, and only later associated with their traditional attributions. For this reason, Ehrman (Forged, p. 225) concludes:

It was about a century after the Gospels had been originally put in circulation that they were definitively named Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. This comes, for the first time, in the writings of the church father and heresiologist Irenaeus [Against Heresies 3.1.1], around 180-85 CE.

So, it is not until some century after the Gospels’ original composition, around the time of the church father Irenaeus, that they were even given their traditional authorial attributions.[20] Incidentally, Irenaeus wanted there to be specifically “four gospels” because there are “four winds” and “four corners” of the Earth (Against Heresies 3.11.8). This was the kind of logic by which the Gospels were later attributed…

Ehrman (Forged, p. 226) goes on to explain:

Why were these names chosen by the end of the second century? For some decades there had been rumors floating around that two important figures of the early church had written accounts of Jesus’ teachings and activities. We find these rumors already in the writings of the church father Papias [now lost, but still partially preserved by Eusebius in Historia Ecclesiastica 3.39.14-17], around 120-30 CE, nearly half a century before Irenaeus. Papias claimed, on the basis of good authority, that the disciple Matthew had written down the saying of Jesus in the Hebrew language and the others had provided translations of them, presumably into Greek. He also said that Peter’s companion Mark had rearranged the preaching of Peter about Jesus … and created a book out of it.

So, we do have references to works written by Matthew and Mark, which date prior to Irenaeus, in the writings of the church father Papias. Unlike the sources mentioned above, however, Papias does make allusions to or quote any passages from these texts, so that it is unclear whether he is referring to the texts that we know today as the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Mark. Papias’ own writings are likewise no longer extant, and so his reference to these works is only preserved in the later writings of the 4th century church father Eusebius. Incidentally, Eusebius (Historia Ecclesiastica 3.39.13) elsewhere describes Papias as a man who “seems to have been of very small intelligence, to judge from his writings.” Likewise, another fragment of Papias tells a story about how Judas, after betraying Jesus, became wider than a chariot and so fat that he exploded…

Here is what Eusebius (Historia Ecclesiastica 3.39.15) preserves regarding Papias’ claim that Mark, an attendant of Peter, had written an account about Jesus:

Now, the presbyter would say this: “Mark, having become the interpreter of Peter, accurately wrote down as much as he could remember, though not in order, about the things either said or done by the Lord. For he had neither heard nor followed the Lord, but only Peter after him who, as I said previously, would fashion his teachings according to the occasion, but not by making a rhetorical arrangement [ου μεντοι ταξει] of the Lord’s reports, so that Mark did not error by thus writing down certain things as he recalled. For he had one intention: neither to omit any of the things which he heard nor to falsify them.”

Regarding the account written by Matthew, Eusebius (Historia Ecclesiastica 3.39.16) records Papias as stating:

These things are recorded in Papias about Mark, but concerning Matthew this is said: “Matthew organized the reports in the Hebrew language, and interpreted each of them as much as he was able.”

Since Irenaeus clearly knew Papias’ works (Against Heresies 5.33.4), he probably drew the connection between these texts and the gospels Matthew and Mark from his testimony.[21] However, a major problem with this tradition, noted above, is that Papias never quotes from the works that he attributes to these authors, and he could very well not be referring to the texts that were later called Matthew and Mark. This is especially true for Matthew, which Papias claims was written in Hebrew/Aramaic, even though the Gospel of Matthew that we possess today is a Greek text. But for Mark as well, Papias’ statement that the gospel “lacked rhetorical arrangement” (ου μεντοι ταξει) does not mesh very well with the internal evidence the text itself, which is actually pretty sophisticated in its plot and rhetorical devices.[22]

Papias himself had never met any of the apostles (Historia Ecclesiastica 3.3.2), and he was relying on a tradition reported by an unknown figure named John the Presbyter, or “elder John.” It could be the case, therefore, that this oral tradition was referring to other, unknown texts that were later conflated with Matthew and Mark. Even if Papias is correctly referring to our Gospel of Mark, however, there are still problems with this attribution. As New Testament scholar Michael Kok, who argues that Papias is referring to the text that is known as Mark today, explains about Papias’ source (The Gospel on the Margins, p. 105):

His main source was the elder John, a figure who remains as elusive as ever. It is unlikely that he was a personal disciple of Jesus; he was probably a second-generation charismatic leader in Asia Minor. We have no clue about the elder’s connections outside Asia Minor or his general reliability. We know that Papias naively gave credence to local traditions about an original Hebrew or Aramaic edition of Matthew and other marvels (Hist. Eccl. 3.39.9, 16). If the foundation laid by Papias is rotten, how can we trust what subsequent writers build on it?

Some have tried to connect this mysterious John the Presbyter, or “elder John,” with John the son of Zebedee, who was a disciple of Jesus.[23] Papias (Historia Ecclesiastica 3.39.4) describes the elder John in a list where he first names “the disciples of the Lord” Andrew, Peter, Philip, Thomas, James, John, and Matthew, and then names in addition two other figures, Aristion and the elder John. A problem with this list is that Papias names John the disciple, who was John the son of Zebedee, already in the same passage, before mentioning the “elder John.” As Michael Kok (p. 59) points out:

A reason for differentiating the latter two figures from the previous list of seven disciples is that it is redundant to name John twice [Historia Ecclesiastica 3.39.4] … Another reason for discerning two distinct figures is that the second John is prefaced with the title πρεσβυτερος (elder)…

Another problem with this identification is that Papias Fragment 10.17 records a tradition in which John the son of Zebedee was martyred alongside his brother James (44 CE), whose death is mentioned in the Book of Acts 12:2 (this fragment is discussed further in endnote 33 below). If this fragment is authentic, Papias could hardly have been reporting that John the Presbyter was John the son of Zebedee, and regardless of this fragment, what Eusebius preserves of Papias’ testimony elsewhere is too ambiguous to claim that Papias had received his information from one of the original twelve disciples. These circumstances make the Presbyter, who is the crucial source behind Papias’ authorial attributions to Matthew and Mark, a completely unknown figure, undermining the reliability of the authorial attribution itself.

Kok (pp. 159-160) also points out that a clear trail can be established for how the figure of John Mark was spuriously assigned to the Gospel of Mark:

1. In the earliest reliable evidence (Phlm 23; Col 4:10), Mark is casually named among a group of Jewish missionary partners of Paul. Mark may have been involved alongside his cousin Barnabas in a short-lived spat with Paul over mixed table fellowship in Antioch (Gal 2:13; cf. Acts 15:36-38), but it is unlikely that this led to Mark’s association with [Peter] as much later literature continues to remember Mark firmly in the Pauline camp (2 Tim 4:11; cf. Acts 12:25; 13:5).

2. In the next stage, the pseudonymous author of First Peter plucks a few of Paul’s co-workers at random, Mark and Silvanus, from the Pauline sphere to suit a centrist vision of the Christian community under the leadership of Peter. First Peter popularly circulated throughout Asia Minor sometime between 70 and 93 CE, leaving its mark on the general milieu of the elder John…

3. The third and most important step was taken by the elders of Asia Minor who assigned an anonymous gospel to Peter through his intermediary Mark and passed the report on to Papias … The rest of the patristic writers are derivative on Papias, though each develops the tradition in distinctive ways.

As such, there is little mystery behind how the authorship of John Mark could have been invented. There is a clear trail for illustrating the process by which 2nd century speculation selected the figure, in order to connect the text with the apostolic authority of Peter and Paul.

As pointed out above, Papias’ claim that the Gospel of Matthew was written in Hebrew/Aramaic, when the Matthew that we possess in manuscripts is written in Koine Greek (and based heavily on the Greek in the Gospel of Mark), is also a major blow to the authorial attribution of this text. Imagine if our earliest outside author to describe Tacitus’ works claimed that he wrote his Histories in Greek, when the Histories that we possess is in Latin! I can guarantee you that, if that were the case, scholars would have many, many more problems with Tacitus’ authorial attribution.

In fact, even Christian scholars like Raymond Brown (An Introduction to the New Testament, p. 210) acknowledge that this discrepancy is a major problem for connecting Papias’ statement with The Gospel of Matthew:

The vast majority of scholars … contend that the Gospel we know as Matt was composed originally in Greek and is not a translation of a Semitic original … Thus either Papias was wrong/confused in attributing a gospel (sayings) in Hebrew/Aramaic to Matthew, or he was right but the Hebrew/Aramaic composition he described was not the work we know in Greek as canonical.

One possible cause for the discrepancy may be that Papias is actually referring to an earlier literary source, which the (otherwise anonymous) author of Matthew later used when writing the gospel. This possible source has sometimes even been connected with the hypothetical “Q source.” Bruce Metzger (The New Testament, p. 97) discusses this possibility, stating:

As a solution of this difficulty it has often been suggested that what Matthew drew up was an early collection of the sayings of Jesus, perhaps in Aramaic, and that this material, being translated into Greek constitutes what scholars today call the Q source. In that case, the first Gospel was put together by an unknown Christian who utilized the Gospel of Mark, the Matthean collection, and other special sources.

If this is the case, however, then the disciple Matthew only authored a collection of Jesus’ sayings, which hardly entails that he stamped his eyewitness approval upon other material in Matthew, such as its legendary infancy narrative or miracles. Furthermore, even if Matthew did author such a source, then this would still entail that the Gospel of Matthew was misattributed when it was connected with his name (or at least that the attribution was oversimplified), by conflating a source for the text with its author.[24]

These are the kinds of issues that make the authorial attributions of the canonical Gospels more problematic than the attributions of many other Classical texts from antiquity. The later Christian sources claiming that the Gospels were written by the apostles or their attendants simply have far more discrepancies, show greater speculation, and involve more implausibilities (or at least oversimplifications) than other, more solid authorial traditions that we possess from the same period, such as for works like Tacitus’ Histories.

Irenaeus’ notion that the author of Luke-Acts was an attendant of Paul likewise comes from speculation over a few passages in Acts where the author ambiguously uses the first person plural (16:10-17; 20:5-15; 21:1-18; 27:1-28:16). However, scholars studying these passages in Acts, such as William Campbell in The “We” Passages in the Acts of the Apostles (p. 13), have pointed out:

Questions of whether the events described in the “we” sections of Acts are historical and whether Luke or his source/s witnessed them are unanswerable on the basis of the evidence currently available, as even the staunchest defenders of historicity and eyewitnessing acknowledge. More important, the fact that Acts provides no information and, indeed, by writing anonymously and constructing an anonymous observer, actually withholds information about a putative historical eyewitness, suggests that the first person plural in Acts has to do with narrative, not historical, eyewitnessing.

Thus, the attribution to Luke the attendant of Paul is likewise unsound, being based on speculation over vague narrative constructions in the text.[25] Luke was probably chosen, in particular, because the pseudonymous letter 2 Timothy (4:11) associates him with Paul’s company (presumably while he was staying at Rome).

Likewise, Ehrman (Forged, p. 227) explains how Irenaeus’ notion that John the son of Zebedee authored the fourth gospel is based on speculation:

The Fourth Gospel was thought to belong to a mysterious figure referred to in the book as ‘the Beloved Disciple’ (see, e.g., John 21:20-24), who would have been one of Jesus’ closest followers. The three closest to Jesus, in our early traditions, were Peter, James, and John. Peter was already explicitly named in the Fourth Gospel, so he could not be the Beloved Disciple; James was known to have been martyred early in the history of the church and so would not have been the author. That left John, the son of Zebedee. So he [Irenaeus] assigned the authorship to the Fourth Gospel.

As can be seen, Irenaeus’ attribution comes from little more than speculation over the identity of an unnamed character in the text. (As will be shown below, the actual internal evidence within John suggests that the anonymous “disciple whom Jesus loved” was probably the fictional invention of an anonymous author.)

Thus, we have a fairly clear trail for how all of the Gospels’ authors were probably derived from spurious 2nd century guesses: Matthew and Mark were based on an oral tradition reported by Papias that originated from an unknown John the Presbyter. Luke was speculated to be an author based on little more than vague narrative constructions using the first person plural in the text of Acts, and John was based on speculation over an unnamed “disciple whom Jesus loved.” Thus, not only is the external evidence weak, but all of it can be completely explained as later, spurious misattributions.[26]

That the attributions were based on speculation is even reflected in the later titles. As I discussed above, the use of the construction κατα (“according to” or “handed down from”) in the titles already signifies that the attributions were redactional and largely speculative. As Ehrman (Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium, p. 42) points out, “Suppose a disciple named Matthew actually did write a book about Jesus’ words and deeds. Would he have called it ‘The Gospel According to Matthew’? Of course not… if someone calls it the Gospel according to Matthew, then it’s obviously someone else try to explain, at the outset, whose version of the story this is.” Thus, the traditional attributions come from later Christians in the 2nd century CE speculating over the different versions of the Gospels to assign apostolic traditions and names to the texts.

Apologists like Blomberg, however, will still attempt another escape hatch. In

The Case for Christ (p. 27), he argues:

These are unlikely characters … Mark and Luke weren’t even among the twelve disciples. Matthew was, but as a former hated tax collector, he would have been the most infamous character next to Judas Iscariot, who betrayed Jesus! … So to answer your question, there would not have been any reason to attribute authorship to these three less respected people if it weren’t true.

It is not clear to me why Matthew, as a reformed tax collector, would be hated next only to Judas, the man who betrayed Jesus. But Blomberg’s claim about these names being “unlikely” attributions is already refuted above, where a clear trail is demonstrated for how the traditional authors were speculated and assigned.

Additionally, Michael Kok has recently argued in The Gospel on the Margins that the attribution to John Mark might not be unlikely at all. The Gospel of Mark was the least favorite gospel among the 2nd century church fathers, and receives the least quotations, compared to the other canonical Gospels, on matters of doctrine and theology. Nevertheless, Kok argues that the Gospel of Mark was too early and too foundational to be removed from the canon. Likewise, the church fathers needed to protect the text from being used by heretical sects, such as those led by Valentinus, Basilides, and Carpocrates. In order to preserve the text’s canonical status, while downgrading its importance to doctrine and theology, therefore, the church fathers attributed the text to the lesser figure of John Mark, who had only imperfectly recorded the teachings of Peter. I discuss Kok’s theory in greater detail in this book review.

Furthermore, Ehrman (Forged, pp. 227-228) explains how the reasoning that apologists use to make this argument is specious at best:

Some scholars have argued that it would not make sense to assign the Second and Third Gospels to Mark and Luke unless the books were actually written by people named Mark and Luke, since they were not earthly disciples of Jesus and were rather obscure figures in the early church. I’ve never found these arguments very persuasive. For one thing, just because figures may seem relatively obscure to us today doesn’t mean that they were obscure in Christian circles in the early centuries. Moreover, it should never be forgotten that there are lots and lots of books assigned to people about whom we know very little, to Phillip, for example, Thomas, and Nicodemus.[27]

Ehrman’s last point about other misattributions is likewise noteworthy. One thing that cannot be forgotten is that, in the context surrounding the Gospels, there were tons of misattributions and forgeries circulating in the early church. As Ehrman (Forged, p. 19) explains, “At present we know of over a hundred writings from the first four centuries that were claimed by one Christian author or another to have been forged by fellow Christians.” In such a context, there were canonical disputes over which texts were authoritative, which led later authors, such as Irenaeus in works like Against Heresies, to speculate and spuriously attribute texts to early figures in the church. As Ehrman (Forged, pp. 220-221) summarizes:

When church fathers were deciding which books to include in Scripture … it was necessary to ‘know’ who wrote these books, since only writings with clear apostolic connections could be considered authoritative Scripture. So, for example, the early Gospels that were all anonymous began to be circulated under the names Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John about a century after they were written … None of these books claims to be the written by the author to whom they are assigned … They are simply false attributions.[28]

Such is the case for why scholars doubt the traditional attributions of the Gospels. To return to Tacitus, however, there was no prevailing context of doctrinal and canonical disputes that would have encouraged a later author to assign the Histories to the Roman senator. Furthermore, while forgery and misattribution could happen with secular texts, scholars have found no evidence of any in the case of Tacitus (here is an article explaining why). The later external references that mention the work simply quote Tacitus as the known author of the text, whereas the Gospels are a clear case of later speculations and misattribution.

Why do apologists attempt to go against the majority scholarly consensus to defend the traditional authors, anyway? The fact is that scholars over the last 150 years have recognized, after thorough study of the New Testament, that we do not possess the writings of a single eyewitness of Jesus. The closest thing we have are the 7 undisputed letters of Paul, who was not an eyewitness, but was writing decades later, and who provides few biographical details about Jesus’ life (I discuss what historical details Paul does provide here, and Ehrman likewise discusses this topic in his series “Why Doesn’t Paul Say More About Jesus?“). Because of this, most of our knowledge of Jesus, outside of a few vague references in Paul, comes from little more than garbled oral traditions, legendary development, and finally, after half a century, anonymous hagiographies, like the Gospels, that are not even written in the same language that Jesus spoke. Our sources for Jesus are thus very problematic and unreliable. None of this entails that Jesus did not exist, but we can only scarcely reconstruct a general biography of his life, let alone prove any of his miracles. For a summary of the minimal historical details that I do think can be said about the life of Jesus, see my essay “When Do Contemporary or Early Sources Matter in Ancient History?”

An apologist may still argue that, even if the Gospels’ authorial attributions are wrong, their real authors may have still had personal access to original eyewitnesses. However, many scholars likewise find this scenario to be unlikely. For Mark, the earliest gospel, Ehrman (Forged, p. 227) explains:

There is nothing to suggest that Mark was based on the teachings of any one person at all, let alone Peter. Instead, it derives from the oral traditions about Jesus that “Mark” had heard after they had been in circulation for some decades.[29]

The situation only gets worse from there, since the anonymous author of Matthew then borrows from as much as 80% of the material in this earlier anonymous source, which itself was based on oral traditions. Likewise, the anonymous author of Luke copies from 65% of the material of the anonymous author of Mark. Furthermore, the author of Luke even suggests that he did not have personal access to eyewitnesses, since he specifies in the prologue of his gospel (1:1-2) that he was making use of previous written accounts (none of which he identifies by name, but we can tell that he copied material from Mark), which themselves were based on traditions that were “handed down” over a span of time (allegedly from distant, original eyewitnesses, although the author of Luke names none).

John is the only gospel to claim an eyewitness source, and yet the author does not even name this mysterious figure, but simply refers to him as “the disciple whom Jesus loved.” This is hardly eyewitness testimony, and it is probably the case that the author(s) of John invented this figure. One possibility is that the anonymous beloved disciple is a character already identified within the text. Verbal parallels suggest that the anonymous disciple may be Lazarus from John 11 (verses 1; 3; 5; 11; 36), whom Jesus raises from the dead in the passage.[30] This Lazarus is likely based on the retelling of a story about an allegorical Lazarus in Luke 16:20-31. In the parable, Lazarus is a beggar who was fed by a wealthy man who dies and goes to Heaven, but the rich man dies and goes to Hell. The rich man begs Abraham in Heaven to send Lazarus to warn his family, since, if someone from the dead goes to them, they will repent. In Luke, Abraham refuses to send Lazarus from the dead, arguing that people should study the Torah and the Prophets to believe and will not be convinced even if someone from the dead visits them. In the Gospel of John, however, in which Jesus is more prone to demonstrate his powers through signs and miracles, rather than by appeals to Old Testament verses like in the Synoptic Gospels, the author instead has Jesus raise Lazarus from the dead, so that people might believe in him. The author of John thus very likely is redacting a previous story based on an allegorical character.

Regardless, even if the anonymous beloved disciple is not based on Lazarus[31], the Gospel of John is still extremely ambiguous about this character’s identity. The text even refuses to name him at key moments, such as the discovery of the empty tomb (20:1-9), where other characters such as Mary Magdalene and Peter are named, and yet this character is deliberately kept anonymous. The traditional identification of the disciple with John the son of Zebedee is undermined, among many other reasons, by the internal evidence of this beloved disciple’s connection with the high priest of Jerusalem (18:15-16), which could hardly be expected of an illiterate fisherman from backwater Galilee. The Gospel of John likewise shows signs of originally ending at John 20:30-31, and chapter 21, which claims the anonymous disciple as a witness, is very likely an addition from a later author. The chapter (21:24) distinguishes between the disciple who is testifying and the authors (plural) who know that it is true, suggesting that (even in this secondary material) the anonymous disciple is not to be understood as the author of the final version of the text.[32] Furthermore, the final composition of John is dated to approximately 90-120 CE, which is largely beyond the lifetimes of an adult eyewitnesses of Jesus.[33] In order to compensate for this problematic chronology, the author even had to invent the detail that this supposed eyewitness would live an abnormally long life (21:23) to account for the time gap. This detail is further explained if the anonymous disciple is based on Lazarus, who was already raised from the dead and has conquered death. Ultimately, all of these factors suggest that the unidentified “witness” is most likely an authorial invention (probably of a second author) used to gain proximal credibility for the otherwise latest of the four canonical Gospels.[34]

Given all of the problems with the traditional authorship of John, even Christian scholar Raymond Brown (An Introduction to the New Testament, pp. 368-369) explains: “As with the other Gospels it is doubted by most scholars that this Gospel was written by an eyewitness of the public ministry of Jesus.”

Conclusion

To repeat the majority scholarly opinion, which I discussed at the beginning of this article, from the Oxford Annotated Bible (p. 1744):

Neither the evangelists nor their first readers engaged in historical analysis. Their aim was to confirm Christian faith (Lk. 1.4; Jn. 20.31). Scholars generally agree that the Gospels were written forty to sixty years after the death of Jesus. They thus do not present eyewitness or contemporary accounts of Jesus’ life and teachings.

I discuss in my article “Ancient Historical Writing Compared to the Gospels of the New Testament” why modern scholars doubt that the authors of the Gospels engaged in historical analysis. In this (rather lengthy) additional article I have also worked to explain why scholars doubt the traditional authorship and eyewitness status of the Gospels. Furthermore, I have shown how the same scholarly methods for determining authorship can be used to doubt the Gospels, while confirming the authors of texts for which we have more reliable traditions, such as Tacitus’ Histories.

To summarize some of the same questions that we can ask about Tacitus’ authorship versus the Gospels, here are a few:

Does the titular attribution clearly identify the author, rather than use a grammatical construction that only ambivalently reports a placeholder name as the attribution?

Tacitus

| Matthew

| Mark

| Luke

| John

|

Yes

| No

| No

| No

| No

|

Did the attributed author likely have sufficient literary training to author the work in question?

Tacitus

| Matthew

| Mark

| Luke

| John

|

Yes

| No

| Plausible

| Plausible

| No

|

Does what we know of the author’s biography align with the internal evidence within the text?

Tacitus

| Matthew

| Mark

| Luke

| John

|

Yes

| No

| No

| No

| No

|

Do the earliest external sources who quote passages within the text either treat the work anonymously or refer to it by a different title?

Tacitus

| Matthew

| Mark

| Luke

| John

|

No

| Yes

| Yes

| Yes

| Yes

|

Do later external sources who attribute the work show signs of speculating over the author?

Tacitus

| Matthew

| Mark

| Luke

| John

|

No

| Yes

| Yes

| Yes

| Yes

|

Was there a prevailing context of misattribution, forgery, and canonical disputes surrounding the text that would increase the likelihood of its misattribution?

Tacitus

| Matthew

| Mark

| Luke

| John

|

No

| Yes

| Yes

| Yes

| Yes

|

As has been shown, the same criteria for determining authorship can be applied to the Gospels as for any secular work, like Tacitus’ Histories. When scholars apply these criteria they find the authorial tradition for Tacitus to be reliable and the authorial traditions for the Gospels to be highly problematic. I have provided just one example here in the case of Tacitus, but textual experts likewise have undergone rigorous analysis of other ancient authors, such as Livy, Plutarch, etc., and found the evidence to confirm their authorship.[35] My main advice for determining the author of any ancient text is to start by looking at what previous scholars have found. You will find that mainstream scholars for the last 150 years have found the authorial traditions for authors like Tacitus and Plutarch to be reliable, whereas the vast majority of scholars have doubted the authors of the Gospels.