Old Testament Life and Literature (1968)

Gerald A. Larue

Chapter 25 – Life and Literature of the Late Period

THE next major project facing the people of Jerusalem was the rebuilding of the wall of the city. Zechariah’s dramatic claim that Yahweh would protect the city with a wall of fire (Zech. 2:5) was an inspiring ideal, but in real life a city without a physical wall was open to any wild animal or band of marauders that cared to enter by day or night and, in the event of war, offered no protection from the enemy. As in the days of the erection of the second temple, dynamic and determined leadership was needed to accomplish the rebuilding. Such leadership was found in Nehemiah.

THE WORK OF EZRA AND NEHEMIAH

For information about Nehemiah and his biblical contemporary, Ezra, we are dependent upon the fourth century work of the Chronicler. Although the records were compiled some time after the reported events occurred, there is reason to believe that the Chronicler incorporated accurate "personal diary" material into the narrative. Neh. 1:1-7:73a, the so-called "Nehemiah Memoirs" (and perhaps 13:4-31), have been accepted by scholars without serious challenge as based on genuine autobiographical data from Nehemiah. On the other hand, the so-called "Ezra Memoirs" (Ezra 7-10; Neh. 7:73b-10) have been questioned. If genuine Ezra material is contained in these chapters, it has been so completely overwritten by the Chronicler that attempts to extract the original work are fruitless.

Chronological difficulties confront those who attempt to unravel the sequence of events of this period. Biblical tradition places Ezra before Nehemiah. Ezra, a priest and scribe from Babylon, led a group of exiles to Jerusalem (Ezra 7:1-5). The events recorded in Ezra 7-10 are dated in the seventh year of Artaxerxes (cf. 7:7 f.), and Nehemiah’s work is placed in the twentieth year (cf. Neh. 1:1; 2:1). If Artaxerxes I Longimanus (464-424) is meant, then the first date would be 458/7 and the second, 445/4. If Artaxerxes II Mnemon (404-358) was the king, the dates would be 398/7 and 385/4.

There is reason to suppose that Nehemiah preceded Ezra. Ezra, as an expert in the law of Yahweh, left Babylon with the expressed purpose of interpreting that law to the Jerusalemites (Ezra 7:10), but there is no record of Ezra reading the law to the people until Nehemiah arrived, thirteen years later (Neh. 8:1-8). Why did he wait so long? It can be argued that the event reported in Nehemiah refers to a second reading, a repetition of an earlier ceremony, but the text does not indicate this. Ezra’s prayer refers to the wall of Jerusalem (Ezra 9:9) which was not erected until Nehemiah’s time, although it has been suggested that a low wall previously built around the city had been destroyed and that it was this wall that Nehemiah rebuilt (cf. Ezra 4:23 f.; Neh. 1:3).1 But there is additional evidence. The census list compiled by Nehemiah (Neh. 7:1-73a) fails to include those who returned to Jerusalem with Ezra, whose names are given in Ezra 8:1-20, and there is no indication from the names mentioned in Neh. 1-7 that the Ezra group participated in the rebuilding of the wall. Nehemiah made efforts to increase the sparse population of Jerusalem (Neh. 7:4; 11:1-2), but Ezra seems to have worked in a flourishing city (Ezra 9:4; 10:1). Finally, it seems strange that Artaxerxes would have appointed two officials to Judah, giving each about the same amount of authority and status; and what is more strange is that these two officials, both committed to the welfare of Jerusalem and Judah, appear to have ignored one another within the limited confines of.Jerusalem.2

A number of solutions have been proposed for the sequence problem. One that is widely accepted suggests that Nehemiah came under Artaxerxes I Longimanus (465-424) or in 445/4, and that Ezra came under Artaxerxes II Mnemon (404-358), or in 398/7. It has also been suggested that the Chronicler simply reversed the dates and that Nehemiah came in the seventh year of Artaxerxes I or in 458/7, and Ezra in the twentieth year, or 445/4. It is possible that the seventh year in Ezra 7:7 should read the "thirty-seventh year," or 428/7.3 It must be admitted that the dating issue is still unresolved. The accumulated evidence indicates that Nehemiah preceded Ezra, and we shall proceed on that premise without attempting to provide precise dates for Ezra, although placing him in the reign of Artaxerxes II in 398/7 seems, at this moment, to be the best solution.4

Some help for dating Nehemiah’s visit is found in the mention of his principal opponent Sanballat (Neh. 2:10, 19; 41:7), governor of Samaria, and Sanballat’s sons in the Elephantine papyrus dated in 4085 (discussed below). From the tone of the letter, it would appear that Sanballat was still governor of Samaria, but was somewhat aged, and that business arrangements were in the hands of his sons. Therefore, it would appear that Nehemiah came to Judah in the twentieth year of Artaxerxes I Longimanus (465-424), or in 445/4.

Read Neh. 1:1-7:4

Nehemiah, a descendant of Jewish exiles in Babylon, lived in Susa, a Persian royal city, and was employed in the court of King Artaxerxes I as the royal cup-bearer, an office of considerable importance and responsibility insofar as the officeholder protected the king from potential poisoning. A delegation of Judaeans came with Nehemiah’s brother, Hanani, to report on the sad condition of Jerusalem. When Artaxerxes was informed, he was most generous, and Nehemiah was given authority and aid to build a wall around Jerusalem. The jealous animosity of the officials in Samaria (possibly because once again they lost control of Judah), and in the Ammonite province ("across the river"), which had delayed other building programs in Jerusalem, proved to be undiminished. Sanballat of Samaria and Tobiah from the Transjordan province,6 aided by Geshem from Arabia hinted that Nehemiah had anti-Persian motives, a suggestion that could have had serious consequences in the light of the rebellion of Persian provinces.

Under Nehemiah’s leadership the walls were built,7 but not without threats from Sanballat, Tobiah, the Arabians and probably opponents from Ashdod, which necessitated armed protection for the workers. Economic difficulties, similar to those mentioned in Malachi 3:5-15, added to the problems, and conditions became so severe that Nehemiah did not accept the stipends legitimately belonging to his office lest he place further burdens on the people. Social inequality and increasing pressures on the poor by the rich demanded corrective measures which Nehemiah was able to bring about. According to Neh. 6:15, the wall was completed within fifty-two days, but another tradition, preserved in Josephus ( Antiquities, Xl:v:8), reports that two years and four months were required.

Read Neh. 13:4-31

In 433, after serving twelve years as governor of Judah, Nehemiah returned to Persia. Within a year or two (the dates are not certain) he was reappointed to Judah. During his brief absence, Eliashib, probably the same man who was high priest (Neh. 3:1), had cleared a storage room within the temple precincts for the special use of Nehemiah’s old enemy, Tobiah the Ammonite. Moreover, tithes due the Levites for temple service had not been paid and Sabbath laws had been completely relaxed. In short order Nehemiah had Tobiah ousted from the temple and instituted action to have tithes paid and Sabbath regulations observed. What appears to have disturbed the governor most was intermarriage between the Jews of Judah and their neighbors, and the resultant hybridization of the language. (Read Neh. 10) A document preserved in Nehemiah 10 but attributed by the Chronicler to Ezra (see Neh. 9) may be an accurate record of a formal agreement prepared by Nehemiah and forced on the Judaeans, by which the very reforms discussed in Nehemiah’s Memoirs (Neh. 13:4-31) were instituted. The fact that the document is not included in the Memoirs may indicate, as M. Noth has suggested,8 that it came to the Chronicler’s hand as a separate source, perhaps from official files.

The information pertaining to Nehemiah’s role as governor is scanty and the Chronicler passes over many years in silence. It is clear that when Nehemiah first came to Jerusalem, he followed a cautious but wise policy of investigation before action. As one committed to the preservation of the national identity of the Jews, he realized that only practices of exclusiveness and isolationism, insofar as they were possible within the framework of Persian government, would maintain Judah as a province and the Jews as a people. The wall about the city afforded security and protection, as well as a sense of identity. Because intermarriage tended to break down Jewish identity by introducing into the Jewish home, society and business, the dialects of the stronger and more affluent peoples around Judah, Nehemiah emphasized marriage among Jews and sought to preserve the national tongue. Casual indifference to Sabbath laws and tithes weakened the binding force of religion, and thus Nehemiah was in close agreement with those rehabilitated exiles who stressed cultic observance and frowned upon religious or family intermingling with non-Jews. As a governor, he seems to follow the pattern established by Zerubbabel, but without the overtones of kingship.9

EZRA

Read Ezra 7:1-10:17

The story of Ezra is contained in the so-called "Ezra Memoirs" which begin in Ezra 7-10 and conclude in Neh. 7:73b-10:39. The genealogical table (Ezra 7:1-5) reveals that Ezra was of a priestly family and that he was a scribe and an expert in the law of Yahweh. As a member of the learned society in Babylon, he was undoubtedly skilled in legal interpretation as well as writing. It is possible that he held some official post within the Persian court.10 His authority and mission, clearly outlined in the copy of the Aramaic letter in Ezra 7:12-26, permitted the return of more exiles and empowered Ezra to investigate Jewish cultic law and appoint officials. Funds for sacrifice and sacred vessels for worship were provided. According to the Chronicler, Ezra became involved in the problem of mixed marriages by priests and Levites almost immediately. Ezra’s demands went much further than those of Nehemiah. Under Nehemiah, the people had agreed to avoid further intermarriage by promising not to permit their children to marry outside of the Jewish inner community (Neh. 10). Ezra demanded divorce of wives and abandonment of children of intermarriage (Ezra 10:18 ff.).

Read Neh. 7:73b-9:38

On a New Year’s Day, Ezra and his Levitical helpers read and interpreted the law to the assembled people of Jerusalem, probably reading in Hebrew and interpreting in Aramaic. just what "law" was involved has been debated, and it cannot be known whether the reading included Deuteronomy, the Holiness Code, or all the revisions made by the priestly writers (P), which would suggest the completed Torah, or just some of the P revisions.11 Subsequently, the people participated in the festival of booths.12 The penitential prayer (9:5-37) placed in Ezra’s mouth by the Chronicler reviews the history of the Jews, stresses election and salvation motifs, and terminates in a rite of covenant renewal (9:38). Possibly the prayer is a psalm borrowed from an older collection by the Chronicler, and the covenant pledge is simply a transition device to lead into Chapter 10.

Ezra’s importance was in strengthening the unifying power of the faith that gave the Jew his identity. In providing the people with an understanding of their religious heritage and the requirements of cultic law, he made adherence to the faith and obedience to the law rest upon comprehension and appreciation as much as upon official decree.

THE JEWS OF ELEPHANTINE

From the Persian fortress known as Yeb on the island of Elephantine at the first cataract of the Nile have come a considerable number of private and public papyri written in Aramaic.13 Some of these documents afford an intimate glance into the life of a colony of Jews who lived in this military outpost of the Perisan empire. Correspondence between the Jewish leaders in Yeb and Bagoas, the governor of Judah, reveal that when Cambyses invaded Egypt (525) the Elephantine Jews possessed a temple of Yahweh (spelled Yahu or Yaho) with five entrances of hewn stone, stone pillars, a cedar roof, doors hinged with bronze, utensils of gold and silver and an altar of sacrifice. This temple was destroyed in 410 at the instigation of the priests of the ram-headed god Khnum. In a letter to Bagoas requesting permission to rebuild the temple, reference was made to the sons of Sanballat, governor of Samaria, apparently the same official with whom Nehemiah had come into conflict. No written reply from Bagoas was found, but a record of his words as reported by an emissary grants permission to rebuild the temple with an altar for incense and meal offerings, but no mention is made of an altar for sacrifice. The temple was restored and remained in use until it was again destroyed, probably by Pharaoh Nepherites I (399-393).

Some evidence of religious syncretism appears in a "treasurer’s report" of temple contributors recording funds collected for Yahweh, Eshembethel and Anat-bethel or Anat-Yahu. There is also reference to "the gods." The element "Bethel" in two of the names appears as a divine name in Aramaean contexts between the seventh and fourth centuries, and the name Anat is the name of a Canaanite goddess in the Ugaritic pantheon. No information about beliefs concerning these deities has been found. Clearly, these Elephantine Jews were not governed by Deuteronomic regulations calling for a single sanctuary in Jerusalem and demanding worship of Yahweh alone.

In addition to providing information about the theological deviations of this particular group of Jews, the Elephantine materials have aided in fixing Nehemiah’s chronology. The mention of the sons of Sanballat in a document written in 410, assuming that Sanballat is the same individual mentioned in Nehemiah’s memoirs, places Nehemiah in the reign of Artaxerxes I and dates his visit to Jerusalem in 445/4.

RUTH

There were those who disagreed with the teachings that tended to divide the Jewish community by denigrating marriages between Jews and non-Jews, and by seeking to isolate Jewish life and religion from immediate intercourse with the non-Jewish world. Reaction against the particularists was not expressed through polemics or forthright statements of opposition so far as we can tell, but rather through short stories or novellen as they are labeled by form critics. This literature of response quietly communicated its points of view and taught its lessons.

Read Ruth

One such story, the book of Ruth, is set in the period of the Judges. From the opening sentence, which is in classical story-telling style, the narrative is a model of excellence. The opening six verses set the stage for all that is to follow, recording the migration of a Hebrew family from Bethlehem in time of famine, the marriage of the two Hebrew sons to Moabite women, and the death of the male members of the group. The remainder of Chapter 1 records the return to Bethlehem of Naomi, the bereaved wife and mother, with Ruth, her Moabite daughter-in-law. The magic of the narrator’s art is clearly seen in Ruth’s statement in 1:16-17, which has been recognized as one of the most beautiful expressions of human affection and relationship. In the second chapter the meeting of Ruth and Boaz, a relative of the dead Hebrew males, is explained and in the next two chapters Ruth wins Boaz’ love and marries him. The male child born from this marriage is received as the child of Naomi and as the one through whom the name of Ruth’s deceased father-in-law, and hence her dead husband, would be carried on. According to an appendage, the child was the grandfather of King David.

It is widely recognized that the genealogical details in 4:17b-22 are secondary, and are probably drawn from the same source as the Davidic lineage in I Chron. 2:4-15. The story, without the appendage, may have originated in the pre-Exilic period, perhaps in the time of the Judges, circulating in oral form before being written down. As such, the story is an idyll, recording the friendship of two women, one Hebrew and the other Moabite, who have lost their husbands and relating how they managed to preserve the family name. The presence of Aramaisms and words associated with post-Exilic Judaism, plus the addition of the genealogy, suggest that the story was recorded in its present form in the post-Exilic period, possibly near the end of the fifth century.

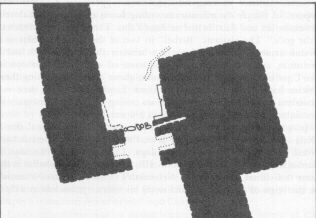

A SKETCH OF THE GATE AREA OF TELL EN-NASBEH. The city gate was the business area of the city. All communication with the outside world passed through it and on the benches outside of the gate the elders sat as they reached decisions. The gate area of Tell en-Nasbeh was paved and provided with a drain to aid in drying the area after a rain. The gates, probably made of timber, pivoted in stone sockets, and when closed rested against a low line of stones placed across the threshold. A slot, which possibly accommodated an iron bar, was found in the main tower and it is assumed that at night this bar was pulled into place to reinforce the upper Portions of the closed gate. The small rooms within the gate were guardrooms. The overlapping walls and massive tower gave the defenders a decided advantage over attackers who would be exposed on both sides when they rushed the gate.

A SKETCH OF THE GATE AREA OF TELL EN-NASBEH. The city gate was the business area of the city. All communication with the outside world passed through it and on the benches outside of the gate the elders sat as they reached decisions. The gate area of Tell en-Nasbeh was paved and provided with a drain to aid in drying the area after a rain. The gates, probably made of timber, pivoted in stone sockets, and when closed rested against a low line of stones placed across the threshold. A slot, which possibly accommodated an iron bar, was found in the main tower and it is assumed that at night this bar was pulled into place to reinforce the upper Portions of the closed gate. The small rooms within the gate were guardrooms. The overlapping walls and massive tower gave the defenders a decided advantage over attackers who would be exposed on both sides when they rushed the gate.

It was to the elders at the gate that Boaz took the problems involved in his marriage to Ruth (Ruth 4:1 ff.) . Other references to the gate as a place of business, judgment and gossip are Deut. 22:24 f.; 25:7 ff.; Amos 5:10, 12, 15; Ps. 69:12.

Numerous suggestions have been made about the meaning of the story. It has been described as a tale told for enjoyment, and there can be no doubt about this evaluation. The fact that Ruth was a proselyte (1:16 f.) has led some scholars to suggest that the story teaches that foreign women could be blessed by Yahweh, and it must be agreed that this point is made in the account. The most common understanding of the purpose of the editor in formulating the story, as we have it, is that it constitutes a protest against the prohibition of marriages between Jews and non-Jews. At a time when the arguments were loudest, the quiet voice of the story-teller pointed out that David, the prototype of the ideal king, was descended from a mixed marriage. Surely if such a one as David had come from such a union, all mixed marriages could not be bad! To make this point, the unknown editor-teacher only had to identify the Boaz of the Ruth-Naomi story as the Boaz in David’s ancestry, and to accomplish this it was only necessary to add a portion of David’s genealogical table.14

The Levirate marriage, originally binding upon brothers in a family (Deut. 25:5-10)15 was extended to include the next-of-kin, but the obligation in this case was not binding, as Ruth 4:3-6 reveals. Boaz became the go’el, the redeemer, when he acquired the family land and Ruth, declaring his intention to perpetuate the name of Ruth’s dead husband and father-in-law.

JONAH

Read Jonah

Like the book of Ruth, the story of Jonah is a novelle telling of a reluctant prophet, who demonstrated his unfitness for his task by attempting to flee from the responsibility of preaching impending doom and urging repentance upon the Assyrians of Nineveh. The hero, Jonah ben Amittai, is an eighth century prophet of the northern kingdom who was active during the reign of Jeroboam II (II Kings 14:25). The opening chapter of the book records Jonah’s attempt to flee from Yahweh. In the second chapter Jonah is transported to Nineveh in the belly of a giant fish. The third chapter tells of Jonah’s successful mission which, to his dismay, resulted in total repentance and the sparing of the city. In the final chapter the angry, sulking prophet is rebuked by God and shown the littleness of his attitude.

Despite the pre-Exilic setting there is evidence that the story was written in the post-Exilic period.16 The language, like that of Ruth, is characterized by Aramaisms and Hebrew vocabulary and style common in post-Exilic writings. Nineveh is described as though it were a great city of the past (3:3) and in exaggerated terms. The writer employs the universalistic spirit of Deutero-Isaiah which is not found in pre-Exilic literature. It is possible that some facets of the story may have been in circulation earlier, but this cannot be known for sure. In its present form, the writing appears to fit best into the post-Exilic period, about the end of the fifth or the early part of the fourth centuries.

Despite the use of an historical figure as the hero, the account is fiction, not history. The fictional nature can be recognized in the account of Nineveh’s repentance, which included kings, nobles, the populace and animals-all fasting and wearing sackcloth (3:6-8) The attempt of a man to flee a universal God by going to sea, and the delivery of that man by fish, cannot be accepted as anything but delightful, entertaining story-telling, designed to amuse even as it informed.

The unity of the work has been questioned, for 2:3-9 interrupts the normal flow from 2:1 to 2:10. The prayer-psalm fits Jonah’s situation only in the most general way, and no reference is made to his plight in the fish’s belly. It is possible that the writer of the story inserted the psalm, but it is more likely that a later editor added what he deemed to be an appropriate prayer.

As a good story-teller, the author’s purpose was to hold his audience as he made his point. In reaction against those who waited with longing for Yahweh to establish the kingdom of the Jews and punish Israel’s enemies, the author of Jonah called upon his countrymen to respond to the teachings of Deutero-Isaiah and his followers and to recognize their responsibility to their fellow men. Yahweh was a universal deity and was concerned about those outside of the chosen people, wishing to extend divine compassion to all, including Israel’s enemies. To dramatize the extent of Yahweh’s concern, the writer chose Nineveh, conqueror and destroyer of the northern kingdom and hated oppressor of Judah-a safe choice since the power of both Assyria and Nineveh had been broken. Jonah represented Judah, called by Yahweh through Deutero-Isaiah to be a light to the nations, but refusing to be concerned about anything or anyone not Jewish and unhappy because Yahweh had not punished or destroyed their enemies. The author’s missionary appeal is made without any zealousness for proselytizing, but rather out of compassion for mankind and in the conviction that Yahweh as a deity "slow to anger and abounding in hesed" (4:2) wished to forgive any who would repent. Repentance of those outside Judah could come only when the Jews accepted their responsibility for bearing witness of Yahweh’s gracious and redeeming mercy beyond their own borders and outside of their own family.

Endnotes

- R. A. Bowman, "Ezra: Exegesis," The Interpreter’s Bible, III, 649 ff.

- Cf. Ibid., pp. 562-563 for a more extensive list of sequence problems.

- Cf. Ibid., pp. 563, 624; Jacob M. Myers, Ezra-Nehemiah, The Anchor Bible (Garden City, New York: Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1965), pp. xxxvi ff. for a more detailed development of arguments.

- Cf. Eissfeldt, The Old Testament: An Introduction, pp. 552 ff.

- Cf. ANET, p. 492; DOTT, pp. 260-265.

- Both Sanballat and Tobiah appear to have been Yahwists. Cf. J. Bright, A History of Israel, p. 366.

- The descriptions given in the book of Nehemiah are important for studies of the ancient city of Jerusalem. Cf. M. Burrows, "Nehemiah 3:1-28 as a Source for the Topography of Ancient Jerusalem," Annual of the American Schools for Oriental Research, XIV (1934), 115-140; M. Avi-Yonah, "The Walls of Nehemiah," Israel Exploration Journal, IV (1954), 239-248; K. Kenyon, "Excavations in Jerusalem 1961-1963," BA, XXVII (1964),34-52.

- Martin Noth, A History of Israel, p. 329.

- It is possible that Nehemiah, as cup-bearer to the king, was a eunuch and therefore would not have been acceptable as king, even if he had had such ambitions. Cf. "cup-bearer" in W. Corswant, A Dictionary of Life in Bible Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1960) ; or in The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible.

- Cf. Myers Ezra Nehemiah, pp. 60-61 for a discussion of possible offices and for a different analysis; cf. Noth, The History of Israel, pp. 331 f.

- Cf. Bowman, op. cit., pp. 773 f.

- Neh. 8:13-18; cf. Lev. 23:39 ff. and note the variations.

- See ANET, pp. 491 ff. for selected documents.

- In a very cogent argument, it has been suggested that David really was of Moabite descent and that the book of Ruth was designed to explain the nature of that relationship and to demonstrate that David was truly an Israelite. Cf. Gillis Gerleman, Ruth, Biblicher Kommentar, Altes Testament, XVIII (Neukirchen Kreis Moers: Neukirchener Verlag, 1960), 5 ff. For a cultic explanation, cf. W. E. Staples, "The Book of Ruth," American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, LIII (1937), I45-157.

- In the story of Tamar and Judah, the father-in-law was involved; cf. Gen. 38.

- Yehezkel Kaufmann, The Religion of Israel, pp. 282-286, maintains the eighth century date. For an Exilic dating, cf. W. Harrelson, Interpreting the Old Testament, pp. 359 ff.

Old Testament Life and Literature is copyright © 1968, 1997 by Gerald A. Larue. All rights reserved.

The electronic version is copyright © 1997 by Internet Infidels with the written permission of Gerald A. Larue.