Was Christianity Too Improbable to be False? (2006)

[See Introduction]

Richard Carrier

2. Who Would Follow a Man from Galilee?

| 2.1 Two Key Problems 2.2 Getting the Context Right 2.3 Working Class Rabbi 2.4 The Galilean Connection 2.5 The Gospel of John 2.6 The Role of Messianic Prophecy 2.7 Why a Virgin Birth? 2.8 Conclusion |

2.1. Two Key Problems

James Holding points out that “the Greco-Roman world was rife with what we would call prejudices and stereotypes,” and far more starkly than we are used to in our own society. That is correct, but not everyone shared the same prejudices. Thus Holding makes a false generalization when he claims that Gentiles would not listen to Christians plugging a Jewish deity. We already know that many Gentiles flocked to Judaism even before Christians came along, either converting to it, supporting it, or holding it in high esteem. We also know that Christianity was most successful in its first hundred years within exactly those groups: Diaspora Jews and their Gentile sympathizers (see Chapter 18).

Once Christianity had saturated that market apparently as far as it could (though still winning a few converts outside it), it began de-Judaizing the religion in order to make it palatable to more Gentiles. We see this process begin in the early 2nd century, and some scholars claim to see it beginning already in the Gospels or even with Paul. This move had become increasingly necessary after the two Jewish wars lost the Jews a lot of their earlier support and sympathy. But, either way, the tactic worked. Christians could then claim that old advantage of persuasion: “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” And they could begin to make their religion more philosophical, more Hellenistic, and less Jewish, all the while claiming to have rendered Judaism obsolete. Thus, even when its Jewishness really did become a problem, Christianity quickly found a way to overcome the handicap. Of course, Holding is right that had Christianity remained obstinately Jewish, it would have failed—and as a matter of fact, the original Jewish sects of Christianity did fail. That’s why the successful Christian movements became increasingly un-Jewish—and why the Western Christian tradition became responsible for perpetuating the enduring bugbear of anti-Semitism.[1]

Holding does appear to concede as much, arguing only that Christianity “never should have expanded in the Gentile world much beyond the circle of those Gentiles who were already God-fearers.” Of course, it didn’t—that is, not much beyond—until later, once issues of evidence could no longer arise, and the successful sects began abandoning their Jewishness, even turning against Judaism. Even so, Christianity did make some early inroads into groups outside the category of Jews and their sympathizers, for the simple reason that Christianity made it easier to convert. A large deterrent against conversion to Judaism was its intense list of arduous social and personal restrictions and its requirement for an incredibly painful and rather dangerous procedure of bodily mutilation: circumcision (in a world with limited anesthetics and antiseptics). Once Paul abandoned those requirements for entry, he had on his hands a sect of Judaism that was guaranteed to be more popular than any previous form of it. Thus, far from Christianity’s increased success being impossible, it was guaranteed. This does not mean people flocked to it in droves—but it does mean that the already significant inflow of Gentiles toward Jewish religion was certain to become significantly greater for its Christian sect.

A second factor that Holding overlooks is what Paul was doing: throughout his letters the impression is clear that he wanted to create a community that would transcend racial and social prejudices and encompass everyone, essentially ending the unwelcome strife between Rome and God’s People by finding a way to unite them in peace.[2] This was to be a New Israel, a community that would realize a socialist utopia of brotherhood by its own efforts, without violence or rebellion. It would be free of the meddling influence of—and manipulation by—the corrupt Sanhedrin, Priesthood, and Rabbinate, and the Roman powers-that-be (economic, political, or military). And it would certainly not be spoiled by the very institutions that Paul saw destroying society—especially distinctions of wealth, status, and race. Paul was fanatic about this, and made heroic efforts to push this agenda by traveling and writing letters throughout the Roman world, putting out fires and strengthening communities. He sought every means of persuasion to realize his dream (“I become all things to all men, that I may by all means save some,” 1 Corinthians 9:19-23, 10:33). Is it really so surprising that he would succeed at this? Certainly he didn’t win over the world. But he was selling a very beautiful and attractive idea, and he clearly had the skills and education to package it in whatever way any given audience would find most persuasive. I think every scholar today would agree that had there been no Paul, there would have been no Christianity as we know it. His role in rescuing Christianity from failure cannot be overlooked. If anyone could sell this new “Judaism Lite” to the Gentiles, it was he.

2.2. Getting the Context Right

So not only did Christianity abandon almost from the start most of the things Gentiles found distasteful about Judaism, but it benefited from one of the most industrious and skillful salesmen the ancient world ever saw. That put Christianity in at least the same standing in terms of potential success as almost every other ancient cult. Holding claims that “the Romans naturally considered their own belief systems to be superior to all others,” yet the Romans were famous for accepting into their society literally every single foreign religion that crossed their doorstep—from the castrated priesthood of Attis to the cosmopolitan Egyptian cult of Isis to the Syrian sun-cult of Emperor Elegabalus, and beyond.[3] Sure, there were intellectuals like Seneca who were horrified by all this, or who, like Plutarch, sought to alter these foreign traditions to be more palatable, more “philosophical.” Yet they could not stem the tide of elites and commoners who embraced all these diverse foreign religions all over the Roman Empire. As far as foreign cults go, Christianity had stepped into a seller’s market.[4]

It is true, as Holding suggests, that Christianity was much like a 1960’s-style counter-cultural movement, but that was its appeal: the Christian missionaries were meeting a new market demand, of a growing mass of the discontented. They were not successful with those well-served by the social system. They were successful with those who were sick of that system, disgusted with it, and yet powerless to do anything about it. And observe how successful the 60’s movement was, despite launching into full flower right on the wings of the most rabidly conservative McCarthy era, and facing violent opposition from every quarter. Christianity wasn’t nearly as disruptive: the Christians organized no mass protests, engaged in no civil violence, dodged no drafts, and paid their taxes—indeed they didn’t even advocate breaking any laws whatsoever, but submitting fully to all the authorities (Romans 13:1-7; see further discussion in Chapter 10).

As to other elements of stigma that might have dissuaded converts, we shall discuss those either below or in other chapters. But as far as the government was concerned, there was no real threat from Christians, and as a result persecution during the first hundred years, especially from the government, was unusual and typically unexpected (we cover this in Chapter 8; but the attitude of Gallio was typical: Acts 18:12-16). For now it is enough to note that there was nothing inherently shocking about Christianity, when compared with all the other strange foreign cults that flourished then—which included numerous sects of Jews, who found their own Gentile converts or supporters.

2.3. A Working Class Rabbi

So there was nothing about being Jewish that prevented Christianity from achieving the small success it did in its first hundred years. But Holding offers a few other stigmas, which he claims would have handicapped it (besides still more that he assigns entire sections to, which we will deal with in their proper order). He rightly notes that many among the snobbish elite looked down their noses at working-class occupations like carpentry, and Jesus was a carpenter—which may indeed be a reason why Christianity won little support from the elite quarter. But other groups did not share this low opinion—and they were the ones the early Christians successfully evangelized: the working class, the poor, those who resented the rich and powerful—and, again, Jews and their sympathizers.

Jews greatly admired tradesmen, and usually expected their rabbis to master a trade. The greatest and most revered rabbis of the period had practical trades: Hillel was a woodcutter, Shammai a carpenter. This was typical throughout the great rabbinical tradition. Jehuda was a mechanic, Jose a tanner, and Jochanan the Sandaler was, as one can tell from his name, a sandal-maker.[5] Paul himself was a tentmaker (Acts 18:3). Does it sound like these people or their admirers would have scorned the idea of revering a carpenter? Not at all. In the Mishnah, Rabbi Gamaliel said, “Fitting is learning the Torah along with a craft, for the labor put into the two of them makes one forget sin.” Indeed “all learning of Torah which is not joined with labor is destined to be null and cause sin” (Mishnah, Abot 2.2a-b). Rabbi Jehuda said, “Whoever does not teach his son a trade teaches him robbery” (b. Gemara 29a), a proverb almost identically embraced by pagans, as expressed by a leading Platonist, “if a man will not dig or knows no other profit-earning trade, he is clearly minded to live by stealing or robbery or begging” (Xenophon, Economics 20.15). Rabbi Shemaiah even said we should love work.[6] And every member of Essene communities was expected to ply a manual trade—this was part of its anti-elitist vision and one of the very reasons people joined it. And of Jewish sects, Christianity resembles the Essenes more than any other, both in its moral ideals and its consistently anti-elitist rhetoric.[7]

Christianity in the first century was most successful among Jews, as well as Gentiles who shared or were sympathetic to Jewish values. But what about outside those groups? There, Christianity was most successful among the middle and lower classes, especially targeting craftsmen and other middlemen whom the aristocracy often scorned (see Chapter 18.4). Obviously, tradesmen, middlemen, and the lower classes didn’t look down their noses at themselves (see Chapter 12). In other words, outside the arena of Jewish values, Christianity was most successful among those who would not have looked down on a carpenter, while it was least successful among those who did. Therefore Holding’s argument is irrelevant to what actually happened.

If logic is not enough to prove that pagan tradesmen held their own class in high esteem, we have evidence. In Lucian’s account of his education (My Dream) he explains how his family sought to improve his prospects by buying him an apprenticeship to a stonecutter, after considering several other trades—in the course of which all his friends and family argued for the value and respectability of becoming a tradesman. We also have countless examples of Greek and Roman tradesmen boasting of their jobs in inscriptions and reliefs carved on their homes and tombstones, and of trade guilds boasting in public inscriptions of their recognition, membership, or accomplishments. Clearly there had to be a substantial segment of the population that thought well of such achievements.[8]

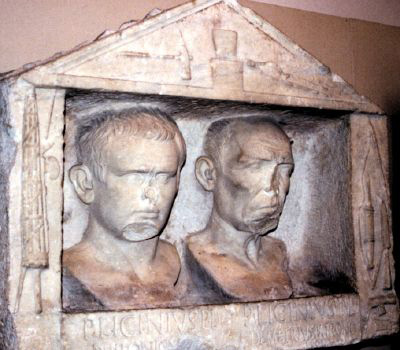

I photographed an example myself when I visited the British Museum:

Publius Licinius Philonicus and Publius Licinius Demetrius (c. 20 B.C., near Rome).

This relief depicts two brothers, celebrating their achievement of freedom (the symbols of their manumission from slavery are shown on the left hand side) as well as their professions: the tools of a smith or minter are depicted above their heads, and the tools of a carpenter to the right. The Publii were clearly proud of their trades and went to considerable expense to boast of them. They would not have bothered if no one was going to admire them for it.

Therefore, the profession of Jesus would not have been a major barrier to conversion. To the contrary, among those the Christians actually evangelized, it was often an asset—and for some Jews it would have been a requirement. Nor was it thought odd to worship a god who held a lower-class occupation. Hephaestus was a blacksmith, Orpheus a musician, Pollux a boxer, and Romulus a shepherd, while some gods were “humiliated” by being sent to earth to be enslaved by human masters—hence Apollo became a shepherd and Poseidon a bricklayer. Yet this did not diminish the worship of any of these deities. As even the Christian author Arnobius admits of his pagan peers, “You represent to us the gods, some as carpenters, some physicians, others working in wool, as sailors, players on the harp and flute, hunters, shepherds, and, even beyond that, mere rustics.” Throwing another carpenter into the mix would hardly make a difference.[9]

2.4. The Galilean Connection

However, the most important stigma Holding brings up here, since he names this entire section after it, is the fact that Jesus came from the Idaho of Judaea: the most hick-and-bumpkin county of Galilee. He summarizes the point very well, worth quoting in full:

Christianity had a serious handicap…the stigma of a savior who undeniably hailed from Galilee—for the Romans and Gentiles, not only a Jewish land, but a hotbed of political sedition; for the Jews, not as bad as Samaria of course, but a land of yokels and farmers without much respect for the Torah, and worst of all, a savior from a puny village of no account [i.e. Nazareth]. Not even a birth in Bethlehem, or Matthew’s suggestion that an origin in Galilee was prophetically ordained, would have unattached such a stigma: Indeed, Jews would not be convinced of this, even as today, unless something else first convinced them that Jesus was divine or the Messiah.

Of course, even by the Christians’ own inflated numbers in Acts, few Palestinian Jews were convinced. But besides that, hasty generalizations abound here. Yes, most of the Jewish elite, especially snobs (most notably, those who would feel threatened by the popularity of any outsider, Galilean or not, gaining moral authority among the people), would balk and snipe at the origins of Jesus. And yes, some Jews of every rank would snobbishly or naïvely expect a messiah to hail from a famous city, just as they expected him to hail from royal blood (and the Christians did struggle to assert just such a claim for Jesus).

But most of those receiving Paul’s mission would have had neither prejudice. Among Gentiles, most by far would know nothing of a past Galilean rebellion, nor would a rebellion be any stigma for those who disliked the Roman order. Among Diaspora Jews, Galilee was nevertheless part of the Holy Land of Israel, and that was always more prestigious than not. In fact, along with Essenes, Pharisees, Sadducees, and a dozen or more others, there was a distinct sect of Rabbis that originated and held authority in Galilee. Holding’s premise that “seditious lands” produced a stigma is also questionable. Italy rebelled against Rome barely a century before in the Social War of 90 B.C., and Asia Minor followed soon after that in the Mithradatic Wars of the 80’s, yet neither territory was stigmatized for it—so why should Galilee have been? There is no evidence it was.[10]

Nor was Galilee such a disrespected hick region, as some have claimed. Apart from the disagreements between Galileans and Pharisees attested to in the Talmud (which were no more derisive than those between Pharisees and Sadducees), within the first hundred years of the Christian mission we have no actual criticism or disdain for the region of Galilee from any source except the Gospel of John. So also for Nazareth, which was not the tiny hovel it is often made out to be. A Jewish inscription from the 2nd or 3rd century confirms that Nazareth was one of the towns that took in Jewish priests after the destruction of the Temple in 66 A.D. Would priests deign to shack up in a despised hick town? And archaeology confirms it may have had a significant stone building before then (perhaps the synagogue that Luke attests to being there in Luke 4:16). Nazareth definitely had grain silos, cisterns, ritual immersion pools, cave dwellings and storerooms, a stone well, and a significant necropolis cut from the rock of Nazareth’s hill, all in the time of Jesus. This was no mere hamlet, but a village inhabited by hundreds experiencing significant economic success.[11]

In contrast, John is alone in having anyone declare anything like the concern of Nathanael: “Can any good thing come out of Nazareth?” (John 1:46). Yet Nathanael is not mentioned in any other Gospel, nor in Acts—so he was either not a real person, or not a very important one in Christian memory. And yet, even according to John, this lone snob is converted after a single conversation with Jesus, while Jesus still lived, and not by any evidence of his resurrection after he died (1:47-49). Since the only man on record scorning a Nazarene origin was still open to the possibility that Jesus was the Christ, and then fairly easily convinced of it, it follows that hailing from Nazareth was no great barrier to conversion, nor was anything like evidence of his resurrection required to overcome that barrier.

Likewise, though Josephus mentions Galilee a total of 158 times in his entire opus, not a single mention contains any hint that the region was looked down upon in the Roman period. In fact, it was the recipient of great honors under Herod: he lavished building projects on “Sepphoris, the security of all Galilee,” which received the coveted and prestigious status of “metropolis,” and he chose to build the great city of Tiberias there, in the very lifetime of Jesus.[12] Herod would not insult Emperor Tiberius by choosing to build and name a new city after him in a scorned backwater. Josephus also reports that Galilee was renowned for its prodigious oil production, and the governorship of Galilee was highly coveted—for a time Josephus was governor of Galilee himself, and certainly appears to have been proud of it.[13]

Even the respected Jewish scholar and sage Eleazar the Galilean came from there. Indeed, the very fact that there was a Galilean scholar famous enough for us to know of him proves Galilee was no hick backwater. Eleazar was also famous for converting the Gentile King Izates to Judaism during the reign of Claudius—exactly when Paul was preaching Christ. So hailing from Galilee did not turn off even well-informed kings.[14] Finally, Josephus records that, combined with Perea, Galilee produced 200 talents in tribute a year, a substantial sum, and most of that came from Galilee. In fact, measured in terms of wealth and number of major cities, Perea was far more a hick backwater than Galilee—yet the revered John the Baptist hailed from and preached in Perea. So coming from a hick backwater was clearly no barrier to prestige or respect.[15]

2.5. The Gospel of John

So why is the Gospel of John the only source we have from the period that denigrates Galilee? Probably for exactly the opposite reason Holding thinks: John included that material deliberately, to exploit the disdain people have for elite snobbery. By playing up the snobbish rejection of any message from Galilee or any prophet from a small rural town, John is playing on popular disdain for exactly such attitudes. His audience would see the Jewish elite in his story the same way someone from a small, wholesome town in upstate New York sees Manhattanite snobs who despise anyone not from “the Big Apple.”

Indeed, the Republican Party in the United States often plays the “small town of mom and apple pie” against the “decadent New York elite” in exactly the same way John does. “See how they look down their noses at you? Don’t you hate that? So don’t follow them—follow us! We’re the party of the common man, of true family values against the hypocrisy and corruption of the big city snobs!” That message resonated even more strongly then than it does today—and yet the same rhetoric still works today. It would have worked even better back then. Christianity was originally a movement for the poor and the disgruntled middle-class. It preached to the very people who despised the Jerusalemite snobbery that John went out of his way to depict. So representing the Jerusalem elite as despising the origins of Jesus actually helped the Gospel. It didn’t hurt it. Having a hero from a “small town” was a big sell—it held out an alternative to elite snobbery: a hero just like the average man, who, just like the average man, suffered under the heel of these big-town jerks.

This is clear from the way John uses this material, repeated in no other Gospel. Nor are any of the key characters ever mentioned in any other source, not even Acts. Consider John 7:41-52:

Some said, “This is the Christ.” But others said, “What, does the Christ come out of Galilee? Doesn’t scripture say the Christ will come from the seed of David, and from Bethlehem, the village where David was?” So there arose a division in the multitude because of him. And some of them would have seized him, but no man laid hands on him.

Already John is saying that though some rejected Jesus on these snobbish grounds, many were not dissuaded by that fact—enough in fact to create a “division” and prevent the Jewish officials from seizing Jesus. Thus, the argument was not that effective against accepting Jesus. And John’s audience is meant to sympathize with those people who rejected the elitist argument. This is clear from the way the story continues:

The officers therefore came to the chief priests and Pharisees, but they said to them, “Why did you not bring him?” The officers answered, “No one told us to.” The Pharisees therefore answered them, “Are you also led astray? Have any of the rulers believed in him, or of the Pharisees? But this multitude that doesn’t know the law are accursed!”

In other words, John is using the fact that the elites (the rulers and Pharisees) rejected the message of Christianity as a point in its favor (which means it must also have been true). John was in effect arguing to the reader, “You common folk, see how they denigrate you, and say you are ignorant and accursed?” Thus, John attests not only to the fact that it is the non-elites who are converting to Christianity (not the snobs whom Holding quotes), but also the fact that this was the very reason they were converting: they despised attitudes like that of the Pharisees depicted here, and John is using that anger as a means to persuade them of the merits of the Christian message.

This is proven by the speech that John now includes in this narrative (in the mouth of Nicodemus, a Pharisee that John alone portrays as gradually coming over to Jesus’s side, cf. 3:1-9, 7:51, 19:39):

Nicodemus (who came to [Jesus] before, and was now one of them) said to them, “Does our law judge a man before it first hears from him and knows what he does?” They answered and said to him, “Are you also from Galilee? Search, and see that out of Galilee no prophet arises.”

Nicodemus thus champions the enlightened ideal of justice,[16] against the very corrupting prejudice the Pharisees are expressing here. To understand how a reader of John would react to this passage, we can rephrase it in a modern context:

Snob: “He’s from Idaho. No great scholar has ever come from Idaho.”

Righteous Man: “What, are we going to judge him before we even know what he’s actually said and done?”

Snob: “You must be from Idaho!”

The insulting fallacy of responding to a valid call for the just and equal treatment of everyone, by accusing the one who makes that call of being a hick themselves, is exactly the sort of thing that enraged the lower classes back then, as it does today. John is getting the audience on his side, and turning them against the Jewish elite. We will examine this class conflict further in Chapter 12.

So the fact that Jesus hailed from Galilee was no barrier to Christian success. On the contrary, among those who actually did convert, it would have been either irrelevant or an actual asset, considering that Galilee was not really so scorned a place, but especially considering how authors like John exploited so effectively what scorn there was, using the very prejudice Holding points to as a weapon in Christianity’s favor. Indeed, the entire Gospel of John is crafted to appeal to that universal human tendency toward reactionary anti-elitism described so well by Richard Hofstadter in the context modern America (though in that case with different social causes). Accordingly, Richard Rohrbaugh concludes from a survey of scholarship on John:

John is almost certainly a Galilean gospel…[aimed at] a group which exists within a dominant society but as a conscious alternative to it, [in particular] an alienated group which had been pushed (or withdrawn) to the social margins where it stood as a protest to the values of the larger society.[17]

That is the very target audience who would side with Nicodemus, not the other Pharisees. Holding’s argument would be correct—for many Pharisees. But not of those who shared the view expressed by Nicodemus—and those were the people Christianity successfully evangelized, far more successfully than the Jewish elite, as John himself admits.

2.6. The Role of Messianic Prophecy

At the same time, an origin in both Galilee and Nazareth was exploited by some Christian evangelists in another way: as confirming that Jesus was the Christ. This is the tactic employed by Matthew, who tells us that the Christ had to come from Nazareth, “that what was spoken through the prophets might be fulfilled, that he shall be called a Nazarene” (Matthew 2:23). Although no such prophecy can be found in the extant text of the Bible, there was no canon at the time, and we don’t know what texts Matthew’s audience may have relied on or how they interpreted them.[18] Matthew also claims (more credibly) that prophecy predicted a messiah who would come from “Galilee of the Gentiles,” a land that was “previously held in contempt, but later made glorious” (Isaiah 9:1), and that he would preach out of the Galilean city of Capernaum (as all the Gospels depict him doing).[19]

Against this point, Holding argues that the Christians could still claim this prophetic “Galilee” connection and yet place the birth of Jesus “in Sepphoris or even Capernaum” for the prestige it afforded, rather than Nazareth. But such a conjecture carries little weight. First, there is no reason anyone had to expect the messiah would come from anywhere but, at most, Bethlehem (e.g. John 7:41-42)—and the only sources we have on his place of birth make every effort to place it precisely there (Matthew 2:1; Luke 2:1-7). The prophetic anticipation of a messiah from Capernaum does not specify birth, but the light of glory, and accordingly all the Gospels place the origin of the Gospel there. Second, as we’ve seen, all evidence shows that the Messiah was expected to be a despised person from Galilee. No prophecy expected a messiah from anywhere prestigious, apart from Bethlehem.

And third, Holding’s conjecture assumes the Christians were eager to lie—which assumes too much, since his entire case depends on the premise that the Christians only told the truth (or at least told enough truth for him to rely on their records for making his case). It may be that Holding’s point still carries weight against those who argue Jesus is a fiction. One might dispute even that, but I see no need to here. It might be true that in such a case a better place of origin would have been contrived for him. After all, once we grant that the Christians were fabricating, then we could presume that an origin at Nazareth might not have occurred to them (though an origin in Galilee would, per Isaiah 9:1-2). But Holding must suppose the Christians told the truth about his origins, so the prospect of inventing a better one is excluded. And for a real hero, his story (true or not) would far outweigh in its persuasiveness any trifle over where he came from—as it did for John the Baptist and Rabbi Eleazar.

We have seen already from the evidence above that had Jesus really come from a small town in a lesser county of Judaea, telling the truth about that would not have harmed the Christian mission, at least with those who would readily sympathize with the rural and middle-class roots of this Hero of the Masses. To be snobbish about where you came from (or what you did for a living) was, indeed, the very kind of thing the Christians despised about the social system they found themselves in, and the very thing they were seeking to escape by creating their own community where all would be equal. This was their intended audience, and for them a Nazarene hero, indeed a hard-working carpenter who didn’t live off the backs of others, would not be a difficult sell.

2.7. Why a Virgin Birth?

Finally, almost as an afterthought, Holding raises the issue of Jesus’s parentage, asking: “How hard would it have been to take an ‘adoptionist’ Christology and give Jesus an indisputably honorable birth” instead of making the harder-to-sustain claim that he was fathered by God? Of course, many Christians did exactly that, i.e. preached some form of adoptionism. Indeed, it is not clear that Paul preached anything to the contrary, and he certainly makes no mention of anything but an ordinary birth into the Davidic line. So it cannot be said that Christianity’s initial success had to be despite a claim to virgin birth—the jury is still out on when that idea entered the tradition. But Holding’s question can be reframed as: “Why would later Christians (like the author of Luke) add to the package something that would be harder to sell?” One reason is that an incarnated god was actually easier to sell to Gentiles than the more difficult idea of an Anointed, who was “Son of God” only in a particular esoteric sense intelligible mainly to Jews. We will address that issue in Chapter 9.

But presuming the Christians wanted to believe (and hence to preach) that Christ was both a man and God Incarnate, there is no other way the story could have sold except by positing a virgin birth to an unmarried woman—and thus the need for these circumstances nullifies any difficulty this idea would pose to persuading mockers. This is because Jesus could only have been God Incarnate if he was not fathered by a human being, while his divine patrimony could only be defended if his mother was, by law, a virgin when she conceived. Besides those requirements, to be the first-born son was the most socially admired, and a virgin conceiving is both a miraculous testimony to his divinity and the best way to gain the Christians the rhetorical advantage of prophetic confirmation.[20] Although the whole idea of the virgin birth would, as Holding suspects, add ammunition to Christian enemies, it would at the same time add appeal to those groups who were more sympathetic to the idea of a Divine Man than a mere “Chosen One.” The overall effect would be a net increase in the popularity of the cult, since more people would be impressed by a miraculously born god-man than by accusations of absurdity or illegitimacy, while those who were quicker to believe the accusations were often the very people who would never have converted anyway.

Even apart from the logical motive to make Jesus virgin-born, there could have been a historical necessity for the doctrine, at least for those who wanted or needed to believe Jesus was literally the Son of God. If Mary really was betrothed to Joseph when she conceived, and Jesus really was her first born, then she had to be a virgin, and therefore Jesus had to be virgin born. For unless Christians were going to lie, they had to argue that Mary’s first child was not produced by a sexual union (since sexless conception was the only way Jesus could be fathered by God), and since Mary was a virgin when she married Joseph (Luke 1:27; if she was not a virgin, unless she was a widow or divorcee, she would have been executed for the crime of fornication per Deuteronomy 22:13-21), Jesus therefore had to be virgin born (i.e. born to a women who had never had sex).

Therefore, the only way Jesus could have been the literal son of God is if Mary was a virgin when she conceived him. And since the idea of virgin-born gods was already in the cultural atmosphere, and was self-evidently miraculous and thus “proof” of God’s intervention in history in a way that would confirm the divinity of Jesus, there was ample motive to develop and promote the idea. This would not have hindered the actual success Christianity enjoyed. And there is no evidence it did.

2.8. Conclusion

Holding says, “What it boils down to is that everything about Jesus as a person was all wrong to get people to believe he was [a] deity—and there must have been something powerful to overcome all the stigmas.” But we have shown that there were no stigmas relevant to the very audience the Christians successfully targeted. To the contrary, everything Holding points to as making their mission harder actually made their mission easier—or had no significant impact on its success at all among those who did flock to the faith. For what Jesus did while on earth is irrelevant to what he could do for you now that he was exalted to the highest throne in heaven, and it was the heavenly Jesus that was sold to the masses, not a mere carpenter from Galilee (see Chapter 1 and Chapter 14).

|

Not the Impossible Faith: Why Christianity Didn’t Need a Miracle to Succeed

Now available as a book, fully updated and reorganized. This is the definitive edition of “Was Christianity Too Improbable to Be False?” Even better than online, improved and revised throughout. Available at Amazon |

Back to Table of Contents • Proceed to Chapter 3

Notes

[1] See Todd Klutz, “Paul and the Development of Gentile Christianity” and Jeffrey Siker, “Christianity in the Second and Third Centuries,” in The Early Christian World, ed. Philip Esler, vol. 1 (2000), pp. 168-97 (esp. p. 193) & 231-57 (esp. pp. 232-35), respectively. On Paul’s criticisms of his fellow Jews (which paralleled that of other Jewish radicals, such as the community at Qumran), see Daniel Boyarin, A Radical Jew: Paul and the Politics of Identity (1997) and Alan Segal, Paul the Convert: The Apostolate and Apostasy of Saul the Pharisee (1992). On the development of anti-Semitism, see: John Gager, The Origins of Anti-Semitism: Attitudes Toward Judaism in Pagan and Christian Antiquity (1985); Peter Schafer, Judeophobia: Attitudes Toward the Jews in the Ancient World (1997); William Farmer, Anti-Judaism and the Gospels (1999); Magnus Zetterholm, The Formation of Christianity in Antioch: A Social-Scientific Approach to the Separation between Judaism and Christianity (2003).

[2] For example, see Galatians 3:28; Colossians 3:15 (w. 3:16-4:6); Ephesians 2:11-19, 4:1-6; and Romans 2:10-11 (indeed, the entirety of Romans chs. 12 and 13).

[3] There are numerous examples of this. The castrated priesthood of Attis was formally set up in the capital city of Rome by the government itself. The cosmopolitan Egyptian cult of Isis won the esteem of the otherwise-maligned Emperor Caligula and became the number one mystery religion among the Roman elite in the 2nd century (which is well-attested to even as far off as the cities of Roman Britain). The Syrian sun-cult of Emperor Elegabalus was formally established in Rome even before his reign, and during his reign became the official state cult. The Phrygian Mithra won the hearts of many among the legionary elite. The Greco-Chaldaean theology of Neoplatonism won the minds of many of the later Roman intelligentsia. The backwater Black Sea cult of Alexander of Abonuteichos won the favor of emperors and governors. And so on.

[4] On all these facts, the evidence is thoroughly documented by Robert Turcan, The Cults of the Roman Empire (2nd ed., 1992; tr. Antonia Nevill, 1996), and Mary Beard, et al., Religions of Rome: Volume 1, A History and Religions of Rome: Volume 2, A Sourcebook (1998).

[5] Michael Rodkinson, “The Generations of the Tanaim: First Generation” in The Babylonian Talmud (1918); and “Hillel and Shammai” in the Jewish Virtual Library (2004). Their trades are evident even in the stories told of them. For example, in b. Talmud, Shabbat 31a, Hillel drives someone off with a builder’s cubit he happened to have in his hand.

[6] Indeed, his complete declaration is more revealing: “Love work. Hate authority. Don’t get friendly with the government” (Mishnah, Abot 1.10b). This expresses the attitude of exactly those for whom Christianity was most attractive. Another example of this resentment of the elite appears in Rabbi Judah’s declaration that even “the best among physicians is going to Hell” (Mishnah, Qiddushin 4.14l); the Christian tale of the woman who bled for twelve years reveals a similar criticism of doctors in Luke 8:43. We might even see this attitude in the prominent disdain held for “the scribes” as a group throughout the Gospels: this may have been a jab at men who claimed authority in the Law yet did not hold what was considered a real working-class job.

[7] Philo, via Eusebius, Preparation of Gospel 8.11.5-12. See also: s.v. “Essenes,” Encyclopedia Judaica, vol. 6 (1971): pp. 899-902; Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 3rd ed. (1997): p. 562; Encyclopedia of the Dead Sea Scrolls, vol. 1 (2000): pp. 262-69. Sources describe as many as six different factions of Essenes, each with slightly different beliefs. In addition, the ancient Therapeutae were probably a faction of the Essenes as well. See: s.v. “Therapeutae,” Encyclopedia Judaica, vol. 15 (1971): pp. 1111-12; Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 3rd ed. (1997): p. 1608; Encyclopedia of the Dead Sea Scrolls, vol. 2 (2000): pp. 943-46. Eusebius found them so similar to Christians that he mistook them as an early Christian sect in History of the Church 2.17. Scholars are agreed that the Qumran community was probably a faction of the Essenes. See s.v. “Dead Sea sect,” Encyclopedia Judaica, vol. 5 (1971): pp. 1408-09. Some Roman elites regarded this counter-cultural community at Qumran with at least a little respect: Pliny, Natural History 5.73, and Dio Chrysostom, via Synesius, Dio 3.2. Finally, for some online guidance, see Sid Green, “From Which Religious Sect Did Jesus Emerge?” (2001).

[8] See Ramsay MacMullen, Roman Social Relations (1974), pp. 70-80. See also Ethele Brewster, Roman Craftsmen and Tradesmen of the Early Empire (1917), whose work was updated by Alison Burford, Craftsmen in Greek and Roman Society (1972). Tradition before the time of Christ also held that Socrates, the greatest and most admired philosopher of the ancient world, was the son of a stoneworker and a stoneworker himself (Diogenes Laertius, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers 2.5.18, citing pre-Christians sources, e.g. 2.5.19, 2.5.20-21). He was also, incidentally, a convicted criminal executed by the state.

[9] See the relevant entries in The Dictionary of Classical Mythology (1951). Quote from Arnobius, Adversus Nationes 3.20.1. On how Jews would respond to the idea of an incarnated god who became an ordinary rabbi, see Chapter 9.

[10] On the sect of Galileans: Hegesippus, quoted by Eusebius, History of the Church 4.22.7; and Justin Martyr, Dialogue of Justin and Trypho the Jew 80. On the Social and Mithradatic Wars, see “Social War” and “Mithradates (VI)” in the Oxford Classical Dictionary, 3rd ed. (1996).

[11] See: “Nazareth,” Avraham Negev & Shimon Gibson, eds., Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land, new ed. (2001); and B. Bagatti, Excavations in Nazareth, vol. 1 (1969), esp. pp. 233-34, which discusses four calcite column bases, which were reused in a later structure, but are themselves dated before the War by their stylistic similarity to synagogues and Roman structures throughout 1st century Judaea, and by the fact that they contain Nabataean lettering (which suggests construction before Jewish priests migrated to Nazareth after the war), as well as their cheap material (calcite instead of marble); pp. 170-71 discusses Aramaic-inscribed marble fragments paleographically dated around the end of the 1st century or early 2nd century, demonstrating that Nazareth had marble structures near the time the Gospels were written (even if not before). Otherwise, very little of Nazareth has been excavated, and therefore no argument can be advanced regarding what “wasn’t” there in the 1st century. Likewise, evidence suggests any stones and bricks used in first century buildings in Nazareth were reused in later structures, thus erasing a lot of the evidence.

On an unrelated note: some have claimed that Luke’s description of the town as built on a hill (4:29) is factually incorrect, but I have confirmed from photographs and archaeological reports that Nazareth was built down the slope of a hill, and many of its houses, storerooms, and tombs were cut from the rock of that hill (while the “brow” of that hill would likely have been cut or built up to provide a place for hurling the condemned, according to Mishnah law, Sanhedrin 6.4).

[12] Josephus, AJ 18.27 & 18.36-37 (JW 2.167-68).

[13] Josephus, Life 228-35 (where he also notes that Galilee contained 240 cities and villages); Life 340-46, 390-93; JW 2.585, 2.590-94.

[15] Josephus, JW 2.95, 3.44; Life 340-46; and see “John the Baptist,” Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible (2000): pp. 727-28, and corresponding maps (and Josephus, AJ 18.116-19). Note that when Herod Antipas received Galilee and Perea as his tetrarchy, he lived and set up his administration in Galilee, thus demonstrating its greater prestige, and when he held a birthday banquet for himself, it was the leading men of Galilee who were invited—we hear no mention of “leading men of Perea” (e.g. Mark 6:21). For more on Galilee, see “Galilee” at JewishEncyclopedia.com.

[16] “He who decides a case without hearing the other side, even if he decides justly, cannot be considered just.” (Seneca, Medea 199).

[17] Richard Rohrbaugh, “The Jesus Tradition: The Gospel Writers’ Strategies of Persuasion,” The Early Christian World, ed. Philip Esler, vol. 1 (2000): pp. 198-30, quote from pp. 218-19; Gospel of John discussed: pp. 218-22. For the situation in modern America, see Richard Hofstadter, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (1963). To be exact, it was not the actual values of the wider society that Christians set themselves against, but the corruption of those values by the elite and their supporters (see Chapter 10). “It is a mode of resistance” which “may take the form” of “passive symbiosis” as the Christian Church did: Bruce Malina & Richard Rohrbaugh, Social-Science Commentary on the Gospel of John (1998), p. 7 (quoting Halliday); cf. “John’s Antisociety,” pp. 9-11.

That there was a major conflict of values and expectations between the upper and lower classes is obvious to any expert in Roman history, and is now the consensus view. See: Michael Grant, “The Poor” in Greeks and Romans: A Social History (1992): pp. 59-82; C. R. Whittaker, “The Poor in the City of Rome” in Land, City and Trade in the Roman Empire (1993): VII.1-25; and P. A. Brunt, Social Conflicts in the Roman Republic (1971). For a discussion of this point in connection with early Christianity, see: Richard Horsley, Jesus and Empire: The Kingdom of God and the New World Disorder (2002); Rodney Stark, The Rise of Christianity (1996), pp. 147-62; Bruce Malina, The Social Gospel of Jesus (2001), pp. 26-35, 104-11.

[18] Some scholars think Matthew may have meant the prophecies that the Messiah would be rejected (which we argued was the case in Chapter 1, and is geographically implied in Isaiah 9:1), in which case Matthew’s tactic is identical to John’s—exploiting the lowly origins of Jesus as a rhetorical advantage: s.v. “Nazarene,” Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible (2000): pp. 950-51.

[19] Matthew 4:12-16, citing Isaiah 8:21-9:2. Note that Capernaum is among the least prestigious cities of Galilee, thus prophecy did not anticipate a messiah from a prestigious city, undermining Holding’s premise that everyone would expect such an origin.

[20] For an explicit reference to the prophesy of his virgin birth as evidence Jesus was the Christ, see: Matthew 1:23 and Justin Martyr, Apology 1.33, who reports the pagans believed Perseus was also born of a virgin (ibid. 1.22, 1.54; so also Dialogue 67). Obviously, the more miraculous his birth, the more persuasive his claim to divinity. Though, as with all the scriptural passages the Christians used to persuade people Jesus was the Christ, Jewish opponents could claim they were interpreting them incorrectly—see Richard Carrier, “The Problem of the Virgin Birth Prophecy” (2003). This was a problem faced by every sect of Judaism: the central issue in their debates was always the interpretation of contended passages in scripture, leaving victory to whomever was the more persuasive, which differed depending on their audience—which is why Judaism never unified itself in regard to how to interpret scripture. Different views always had their loyal adherents. The Christians simply found theirs.

Copyright ©2006 by Richard Carrier. The electronic version is copyright ©2006 by Internet Infidels, Inc. with the written permission of Richard Carrier. All rights reserved.