(2022)

[This essay is a somewhat modified version of Raymond D. Bradley’s opening statement in his debate with William Lane Craig on the topic “Can a Loving God Send People to Hell?” held at Simon Fraser University in January 1994. An expanded version of this essay was published as “Can God Condemn One to an Afterlife in Hell?” in Chapter 21 of The Myth of an Afterlife: The Case against Life After Death in 2015.]

How Should Our Question be Construed?

Universalists versus Exclusivists

How Should We Think of God’s Sending People to Hell?

The Christian’s Trilemma: Jesus’ Views on Hell are either Malevolent or Mistaken or Misreported”

Who will Escape the Tortures of Hell?

How about the Unevangelized and Other Nonbelievers (Including Infants)?

The Problem of Inconsistency

Our Initial Question is One of Applied Logic

A Heavenly Refutation of the Free Will Defense

God’s Foreknowledge of Our Free Acts

Further Proof that (1) and (2) are Inconsistent

William Lane Craig’s God

How Should Our Question be Construed?

William Lane Craig likes to talk about Hell in such sanitary terms as “everlasting separation from God.” This is a favorite dodge of Christian apologists. It makes our question sound rather like:

Can a Loving Father send some of his children to Hawaii?

Think of it like this, and the answer seems obvious: “Why not, if that is where they choose to go?”

Some Christians do in fact think of the question euphemistically, like this. And some like to suppose, further, that when the children find that Hawaii is a bit like Hell—it’s far too hot and the locals are giving them a hard time—Father will relent and welcome them to his mansions on high.

Universalists versus Exclusivists

Such Christians are known as Universalists. They believe that a time will come when God will actualize a perfect world, known as Heaven, in which all of us will live with God in a state of joyous freedom and eternal happiness. I see nothing logically impossible about this idea of Heaven. And, presumably, neither does Craig.

Yet Craig rejects the Universalists’ doctrine because the Bible tells us that the majority of God’s children will excluded from Heaven and sent instead to Hell. And here he is right. The Bible—we both agree—is exclusivist, not universalist.

Keeping Craig’s biblical conservatism in mind, let’s ask a different question.

How Should We Think of God’s Sending People to Hell?

It ought not to be thought of as like Stalin’s sending people to exile (“separation” as Craig calls it) in Siberia. And it ought not to be thought of even as like Hitler’s sending people to the gas-chambers of Auschwitz. For both of these are tame in comparison with the horror of being sent to Hell. At least Auschwitz, Belsen, etc., were death-camps, finite in duration both for those who died and for those who survived. Hell, however, offers no such finality to those of us who are to fill its chambers: none will emerge from its torment, and its tortures will continue forever and ever.

Lest you think I exaggerate, let me quote from what the “Good Book” has to say about the fate of those who are “eternally separated” from God:

[H]e shall be tormented with fire and brimstone in the presence of the holy angels, and in the presence of the Lamb; and the smoke of their torment ascendeth up for ever and ever: and they have no rest day or night. (Revelation 14:10-11)

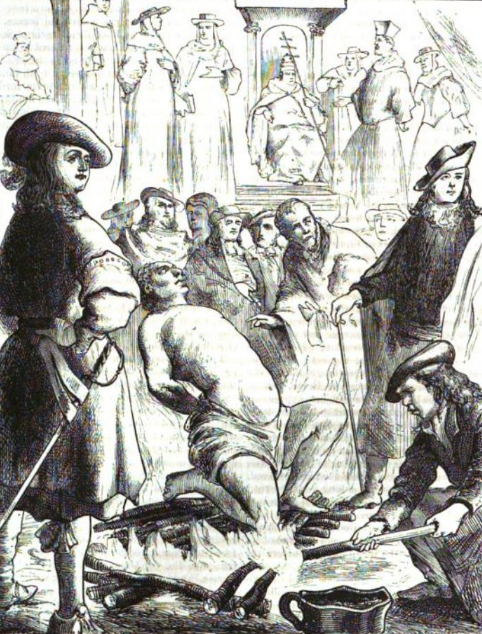

Note that the so-called “Lamb” who features so prominently in these divine spectator sports is Jesus himself (God’s sacrificial lamb). He plays much the same role as does the subsequently sainted Pope Pius V in the accompanying illustration from Harper’s Magazine:

Credit: “The Vaudois” in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine Vol. 41, No. 242 (July 1870): 161-185, p. 168.

Note, too, that Jesus himself is reported as having similar views of Hell. No fuzzy talk of “eternal separation” from him! On a quick count I found twenty or so passages in the Gospel of Matthew alone in which Jesus threatens unbelievers with what he calls “fiery hell” (5:22), i.e., with “eternal punishment” (25:46) in an “eternal fire” (25:41) where there will be “weeping and gnashing of teeth” (25:30).[1]

The Christian’s Trilemma: Jesus’ Views on Hell are either Malevolent or Mistaken or Misreported

What should Christians to say about such passages? They are faced with a devastating trilemma. To renounce them as untrue because malevolent would be to suppose that Jesus was either mistaken or misreported. But if Jesus was mistaken, he can’t be divine. And if Jesus was misreported, the Bible can’t be the true word of God.[2] A believer has no option, then, but to accept the doctrine of hellfire in all its obscenity. Now let’s ask: Who will escape the tortures of Hell?

Who Will Escape the Tortures of Hell?

St. Paul tells us that only those who have been “sanctified [and] justified in the name of the Lord Jesus” will be saved; and the list of the damned—take note—includes fornicators, adulterers, the effeminate, homosexuals, thieves, drunkards, and swindlers (1 Corinthians 6:9-11).

St. Paul, of course, was only echoing Jesus who repeatedly tells us that only those who believe in him will go to heaven. Neither good works, nor generous donations, will get you there. The legions of the damned, according to Jesus, include all who don’t have the right belief, i.e., the belief that he, Jesus, is Lord and Savior. In short, those who will be sent to Hell include all who haven’t—as evangelicals put it—been “born again.” Craig is commendably firm on this. There is “no other name,” he says, whereby we may be saved. On his view even the most saintly believers of other religions are “lost and dying without Christ.”[3] Craig, like Jesus, is an exclusivist.

How about the Unevangelized and Other Nonbelievers (Including Infants)?

But isn’t there a problem here? Since it is a necessary condition of believing in the name of Jesus that you’ve both heard his name and understood its significance, no-one can be saved from Hell if they haven’t been evangelized. What, then, of those who have lived in times or places in which the name of Jesus is unknown or ill-understood? Are we to suppose that a loving God will send to Hell all those who can’t believe, either because they’ve never heard or because, like me, they have heard but find it impossible to believe?

Once more, Craig bites the bullet. Yes, he says, that’s the way it is: “The gate [to salvation],” he likes to remind us, quoting Jesus, “is narrow and the way is hard … and those who find it are few” (Matthew 7:13-14). The exclusion of most human beings on the grounds that they don’t believe in Jesus as Savior, is a simple consequence of the fact that most of them haven’t even heard of him.

Craig, as we’ll see in a bit, knows and appreciates his logic. I do wonder, however, whether he takes the same view of children who die before they understand what all this Jesus-talk amounts to. Will they, too—as St. Augustine believed[4]—be excluded? Infants, he would have to admit, are just as tarnished with original sin (inherited from Adam and Eve) as are others who are in no position to believe. So if—like Craig—we think God justified in sending the unevangelized to Hell on the grounds that he knew, from all eternity, that they would have rejected Christ even if they had heard his name[5], why shouldn’t we think God justified in condemning nonbelieving infants on precisely the same grounds? Would Craig have the courage to tell that to grieving parents?

Now I can understand how those who believe in the God of the Old Testament might see no problem about that god consigning people to Hell. For that god is often depicted as:

- unjust (e.g., he punishes not only sinners but their children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren [Exodus 20:5]);

- unrighteous (e.g., he gave Moses’ soldiers thirty-two thousand captured virgins for themselves while ordering the slaughter of their mothers and brothers who were also prisoners of war [Numbers 31:17-18]);

- manipulative (e.g., he repeatedly caused Pharaoh to “harden his heart” and refuse to let the children of Israel depart from Egypt [Exodus 7:2-4]); and

- cynically vengeful (e.g., he then killed all the first-born Egyptians on the grounds that Pharaoh hadn’t done what he, God, prevented Pharaoh from doing [Exodus 12:29]).

Summing it all up, God even says of himself—in the book of Isaiah—that he creates evil (Isaiah 45:7).

The Problem of Inconsistency

But the God in whom Craig believes is supposed to have more desirable properties, as stated in proposition:

- God is omnipotent, omniscient, perfectly good, just, righteousness, merciful, and loving.

At this point, our question emerges into sharp focus from the fog of euphemistic verbiage. How could this God send the majority of the human race to eternal torture in the fires of Hell?

The problem is that proposition (1), when analyzed, seems logically inconsistent with the following proposition:

- God will torture the majority of humans eternally in Hell for the sin of unbelief even though most of them have never even heard Jesus’ name.

Our Initial Question is One of Applied Logic

As both Craig and I agree: Our initial question is one of applied logic.

Think for a moment and test your own intuitions about (1) and (2). If it would be inconsistent to claim that Hitler was acting lovingly while sending the majority of German Jews and Gypsies to the gas-chambers for lacking the right parentage, wouldn’t it be equally as inconsistent to claim that God is acting lovingly while sending the majority of the human race to roast in Hell for lacking the right beliefs?

For my own part, I think the answer is obvious.

But before proving that (1) and (2) are indeed inconsistent, I’m first going to have to refute a logical argument by means of which Craig thinks he can prove that they aren’t.

A Heavenly Refutation of the Free Will Defense

Craig claims that there is a third proposition:

- God has actualized a world containing an optimal balance between saved and unsaved, and those who are unsaved He will send to Hell.

…which is both consistent with (1) and which, together with (1), implies (2).

Now I agree that if (3) had both these features, then it would indeed follow—by a well-known theorem of logic—that (1) is consistent with (2).

But the trouble is that (3) isn’t consistent with (1), since—as I’ll show—(3) implies a proposition with which (1) is inconsistent.

Just think about it. In talking about an optimal world, Craig is talking about the most desirable world that God could have created given that he wanted to create a world in which people have free will and can exercise it by deciding whether or not to accept Christ. This means that, as he himself has acknowledged in some of his publications, proposition (3) wouldn’t be true unless it were also true that:

- There is no possible world inhabited by creatures with free will in which all persons freely receive Christ.

In other words, (3) implies (4).

But now consider Heaven. Clearly the concept of Heaven is a coherent one. That is to say, more technically, Heaven is a possible world. If it weren’t, not even God or the saved could exist there. Moreover, Craig and other conservative Christians take it to be one that is populated solely by believers who freely acknowledge Christ. That is to say, they are committed to asserting the denial of (4), namely:

- There is a possible world inhabited by creatures with free will in which all persons freely receive Christ.

But this spells trouble for Craig. If (5) is true, then both (4) and (3) are false, since a world in which some people go to Heaven and others are sent to Hell is by no means an optimal one. God can’t be let off the hook, as it were, by saying he couldn’t have done any better without depriving his creatures of their freedom of choice.[6]

Craig’s so-called theodicy goes down the drain.

But worse is to come. For since (5) merely asserts a logical possibility, it is one of those propositions which, if true, is necessarily true. It then follows—in accord with a few more theorems of logic (all of which, I’m sure, are well-known to Craig)—that the denial of (5), namely (4), is necessarily false; that (3), which implies (4), is also necessarily false; and finally, that (3) therefore isn’t consistent with (1) after all. The mere possibility of Heaven shows his free will defense to be a logical fraud.

Having demolished his defense, I’m now going to prove the inconsistency of (1) and (2).

God’s Foreknowledge of Our Free Acts

First, I want to point out that there is a problem about God’s foreknowledge of our free acts.

It’s not that I think that God’s omniscience, and consequent foreknowledge, implies his predetermining what our acts will be or totally deprives us of our freedom, despite the fact that the Bible says that the two go hand in hand.[7]

The trouble lies elsewhere, in the fact that God’s foreknowledge of what the unsaved would do, together with his perverse determination to create them nevertheless, makes him—morally as well as legally—what lawyers call “an accessory before the fact” and therefore responsible at least in part for the outcome. After all, it is—as Plantinga has acknowledged—”up to God whether to create free creatures at all”.[8] Just as we must bear responsibility for the consequences of our freely chosen actions, so must he. The New Testament God, every bit as much as the Old Testament one, creates us as sinners in an evil world, knowing well what the consequences would be for some of us, namely, the worst evil of all, Hell. At the very least, he shares responsibility for these evils. But, obviously, being even partly responsible for the evils asserted in proposition (2) is not consistent with the “perfect goodness” asserted in proposition (1).

Further Proof that (1) and (2) are Inconsistent

Secondly, I can demonstrate the inconsistency of (1) and (2) by appeal to the logico-semantic fact that “good” is a descriptive term which, as it is ordinarily used, allows us to distinguish between possible situations in which it applies and those in which it does not. In saying that someone is good, we commit ourselves to saying that he or she doesn’t act in the kinds of ways that evildoers do. It follows that if we were to describe someone such as Hitler as “perfectly good” despite all his evildoing, we would be playing word games which are not only morally pernicious but intellectually dishonest.

The need to use the term “good” in such a contrastive way holds just as much when we are describing God as it does when describing Hitler. And when it is applied to the descriptions of God given in proposition (1), it yields the following logico-semantic truths:

- A perfectly good being would not torture anyone for any period whatever, however, brief.

- A just being would not punish someone eternally for the sins committed during a brief lifetime but would proportion the punishment to the offense.

- A righteous being would not punish someone eternally for unavoidable lack of belief.

- A merciful being would not be eternally unforgiving to those who have offended it.[9] And finally:

- A loving being would not bring about and perpetuate the suffering of those it loves.

But now the logical inconsistency between (1) and (2) becomes obvious on several scores all at once. For (1), in conjunction with (P1) through (P5), implies that the Christian God won’t do the very things that (2) says he will do.

The answer to our original question—”Can a loving God send people to Hell?”—is that for purely logical reasons she/he cannot. Craig’s concept of a loving God sending people to Hell contains a logical contradiction.

The consequences of all this are momentous. I have shown that we have compelling reasons for not believing in Craig’s sort of God.

William Lane Craig’s God

Finally, let me alert you to something deeply important: all this talk about what God can or cannot do can easily trap us into accepting the underlying presupposition that a God actually exists. But are there any good reasons to suppose that the Christian God, the god of Craig and the Bible, does in fact exist? Or that he loves us?[10]

I’d say “No” for a host of reasons, the most important being that—as we’ve just seen—the Christian concept of a God who sends people to Hell is logically self-contradictory. We therefore have the best of all possible reasons for being atheists and denying the existence of any such God.

As to whether some other god (or gods) exist—e.g., any of the two hundred or so dead ones to whom Mencken dedicated his essay “Memorial Service”[11]—I’m inclined to be an agnostic. In my view, there’s as little reason to believe in the existence of any god as there is to believe in the existence of Santa or the tooth fairy. The fact that we can talk about gods, build them temples, make sacrifices on their behalf, evangelize about them, and persecute those who don’t believe in them, shows only that some of us suffer from what Bertrand Russell called “the cruel thirst to worship”[12] or like to take flights of fantasy into worlds of make-believe and fiction.

Not all fictions are on a par, however. Stories about Santa or the tooth fairy are fairly innocuous. But the Christian fiction—with its story of evils in an afterworld—demonstrably isn’t. Belief in it has been responsible for some of the most horrendous evils of this world: the evils of witch hunts, religious wars and persecution; evils such as those in which the Conquistadors first baptized Indian infants, thus saving their souls, then dashed out their brains so as to ensure that they couldn’t become heretics; evils such as those in which the Inquisition cast nonconforming thinkers into temporal fires so that their souls, thus purified, might escape the fires of eternity.

If there were an omniscient God, he would have known from the very beginning that all these atrocities, and many more, would result from believing in him. He would therefore be as responsible for such evils as that other creature of Christian mythology, the Devil.

Beware of such beliefs. I hope that you will come to see, as I once reluctantly did, that they can be hazardous to your health, not just physically, but intellectually and morally as well.

Notes

[1] Note that the New Testament word “aionios,” which is usually translated as “everlasting” or “eternal,” can also mean “for an aeon, or age.” But what holds for the doctrine of eternal fire must also hold for that of eternal salvation. For it is the same word that is used to talk about both. Thus Matthew 25:46 tells us: “these will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life.”

[2] My maternal grandfather, Baptist minister, padre, and evangelist, reasoned in this way before becoming “born again.” As reported by my grandmother in her biography, Guy D. Thornton: Athlete, Author, Pastor, Padre (Auckland, NZ: Scott and Scott, 1937), he reasoned—prior to his conversion—that it is “impossible to conceive of a God of love punishing eternally the sins committed in a short lifetime…. Eternal punishment is unthinkable. Christ must have been misreported by the authors of the Gospels…. If Christ has been misreported, what reason is there for anyone to deny that he has been altogether misreported, and that the whole of the New Testament is nothing but a collection of fables?”

One might try to escape between the horns of the malevolent/mistaken/misreported dilemma by supposing that Jesus was merely employing misleading metaphor. But that supposition, too, opens a can of interpretational and moral worms. The interpretational problems arise from the fact that if it is up to us, not Jesus, to say what he meant, then the interpretational floodgates—once thus opened—are unlikely to stem the flood of heresies that may ensue. For where should we stop? Is his talk of his Father in Heaven, his Second Coming, or of the Day of Judgment, also mere metaphor? The moral problems arise from the fact that Jesus, as God, must surely have known that he would be taken so seriously by his own followers that many, e.g., the Spanish Inquisition, would create Hell on earth in a misbegotten attempt to save sinners from a still-worse Hell in the afterworld. As someone who would know the consequences of his religious hyperbole, he would be an accessory before the fact of these Christian barbarities and therefore partially responsible for them.

[3] William Lane Craig, “‘No Other Name’: A Middle Knowledge Perspective on the Exclusivity of Salvation Through Christ. Faith and Philosophy Vol. 6, No. 2 (April 1989): 172-188, p. 187.

[4] Thomas Talbott, “The Doctrine of Everlasting Punishment.” Faith and Philosophy Vol. 7, No. 1 (January 1990): 19-42, p. 22.

[5] John 6:64: “Jesus knew from the beginning who they were who did not believe.”

[6] Note that I’m nowhere suggesting that there has to be a “best” possible world. It suffices, for purposes of my argument, that there be a better one than that which Craig thinks “optimal.”

[7] There is, however, an associated problem regarding God’s predetermination of who will and who won’t be saved. Foreknowledge and predestination go hand in hand. Romans 8:29: “For those whom He foreknew, he also predestined…” Ephesians 1:4-5, 11: “He chose us in Him before the foundation of the world…. In love he predestined us to adoption as sons through Jesus Christ unto himself, according to the kind intention of his will.” Ephesians 2:8-10: “For by grace are ye saved, through faith; and that not of yourselves: it is the gift of God. Not of works, lest any man should boast. For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus unto good works, which God hath before ordained that we should walk in them.”

[8] Alvin Plantinga, The Nature of Necessity (Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1974), p. 190.

[9] A non-hypocritical God would surely obey his own moral injunction to love, and hence forgive, his enemies. “I say unto you, love your enemies” (Matthew 5:44).

[10] The Scriptures themselves contradict Craig’s belief in a God who loves us all. For instance, in Malachi 1:2-3, repeated in Romans 9:13, God is reported as having said: “Jacob have I loved, but Esau have I hated.” So much for God’s universal love! In Romans, St. Paul continues thus: “What shall we say then? There is no injustice with God, is there? May it never be! For He says to Moses, ‘I will have mercy on whom I will have mercy, and I will have compassion on whom I will have compassion.’ So then it does not depend on the man who wills or the man who runs, but on God who has mercy.” So much for our free will!

[11] H. L. Mencken, “Memorial Service” in Philosophy: The Basic Issues ed. E. D. Klemke, A. David Kline, and Robert Hollinger (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1986). (Originally published 1922.)

[12] Bertrand Russell, “A Free Man’s Worship.” Independent Review (December 1903): 415-424; reprinted in Mysticism and Logic (New York: Doubleday Anchor Books, 1957). p. 44.

Copyright ©1994 by Raymond D. Bradley. This electronic version is copyright ©2022 by Internet Infidels, Inc. with the written permission of Raymond D. Bradley. All rights reserved.