Old Testament Life and Literature (1968)

Gerald A. Larue

Chapter 5 – The Land

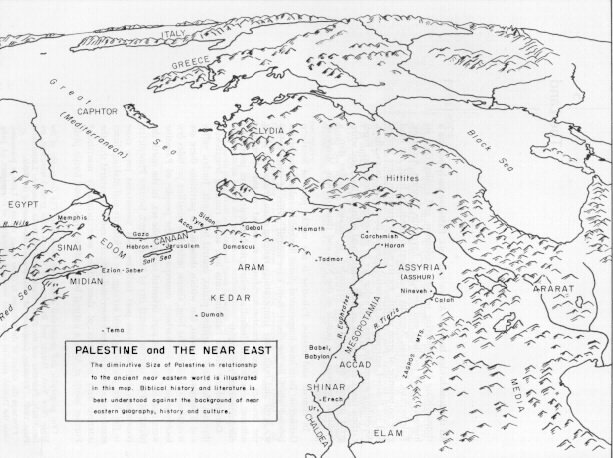

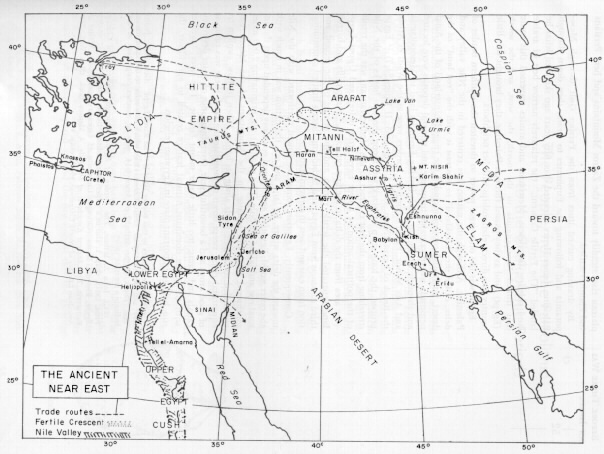

AS the land-bridge between Africa and Asia, Palestine early became a thoroughfare for wandering peoples, tradesmen, and armies. Over its highways came products and ideas from Egyptians, Hittites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Aegeans and desert nomads. In itself, the land gave no promise of great wealth, for its mineral resources were modest and its limited agricultural potential ranged from poor to excellent, depending upon the area. Its value lay in its strategic location. From earliest times, it served as an inter-continental cultural link, and when great nations developed and expanded, it became a buffer state, a cushion, between the people of the Nile and those of Asia Minor or Mesopotamia.

In climate and terrain, Palestine is not unlike parts of Southern California. Both have long coastal plains flanked by inland mountains beyond which lie the desert. Both have inland bodies of water below sea level and both have temperatures ranging from temperate along the beaches, to cool in the highlands, to torrid on the deserts in summer. Nor is there dissimilarity in agricultural products, providing adequate water is available.

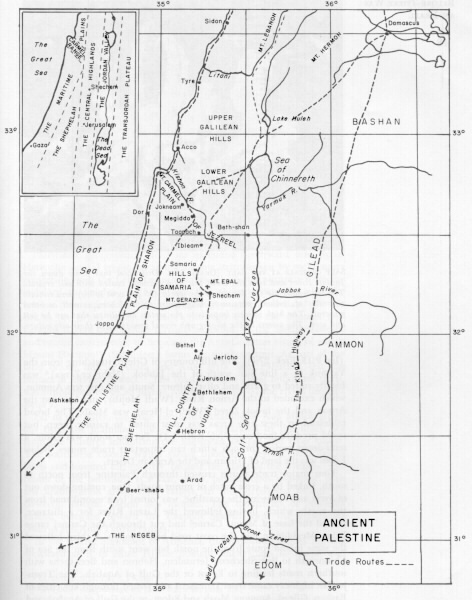

Geographers1 divide Palestine into four strips running length-wise through the land: maritime plains, central highlands, Jordan valley and Transjordan plateau, but within these major partitions there are several subdivisions. The long, almost unbroken coastline provides few locations suitable for harbors; consequently, the peoples of Palestine were not, for the most part, oriented toward the sea. In the north the island of Tyre and the coastal city of Sidon, which became Phoenician possessions, had adequate port facilities, but mountains press close to the shore, providing scant acreage for agriculture and making direct communication with the hinterland difficult, and it is natural that the interests and industries of these cities were primarily maritime.2 Further south at Acco, a natural bay bordered by a broad fertile plain formed an adequate but poorly sheltered harbor with access to major inland highways. Below Mount Carmel, which breaks into the coastline, was the heavily forested Plain of Sharon which, in turn, merged into the more southerly Philistine Plain.3 Small harbors were located at Dor, Joppa (used by Solomon, II Chron. 2:16), and Ashkelon. The Philistine Plain broadened to the south, and inland the sandy seacoast became a gently undulating hinterland, well watered, and ideal for growing grains, olives and grapes. This hilly country, called Shephelah or "lowland" in the Bible (cf. I Kings 10:27; Jer. 17:26, 32:44, 33:13), reaches a height of 1,500 feet in the south, and can only be seen as "low" when viewed from the central highlands.

Running as a backbone throughout the length of Palestine are the central highlands, grouped into three clusters. The upper Galilean hills in the north are rugged and high (nearly 4,000 feet) . In lower Galilee, to the south, the hills are not so high and fertile valleys between permit cultivation of vineyards, orchards and olive groves. At the foot of the hills, the Plain of Jezreel spreads southward to the Carmel range, linked to the Plain of Acco by the Kishon River. The strategic importance of the highway that ran through Jezreel is demonstrated by the powerful fortified cities that protected it: Jokneam, Megiddo, Taanach, Ibleam and Beth Shan.

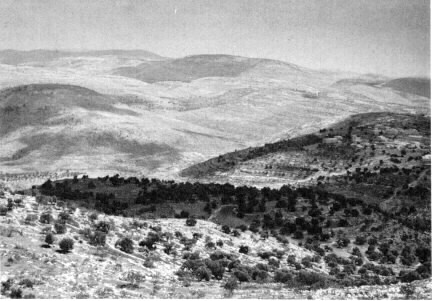

THE SHEPHELAH WEST OF HEBRON. Olive trees dot the slopes of the hills which have been terraced to prevent erosion. In the rich bottom land between the hills the cultivated fields bear various kinds of grains and vegetables. The houses on the hill to the right are constructed of native limestone.

The hills of Samaria, or the Ephraim highlands, form the next cluster. One arm of these mountains, the Carmel range, extends westward to the Mediterranean, separating the Plain of Acco from the Plain of Sharon. At the center are the mountains Ebal and Gerizim, with the road linking Samaria and Shechem running between. Further south the Ephraim highlands become the Judaean hills, rising gently from Jerusalem (2,600 feet) to the hills above Hebron (3,000 feet) and descending abruptly further south to Beer-sheba (1,200 feet) . Beyond Beer-sheba the hills become part of the desert, the Negeb or "dry land" (Gen. 12:9, 13: 1; Deut. 1: 7).

Survival in the Negeb depended upon careful hoarding of water, despite the fact that on occasion late spring rains may leave surface pools standing in May. Westward, the Judaean hills became the Shephelah, descending to the Philistine Plain. Strategically located fortresses in the Shephelah formed a first line of defense for the important hill cities of Hebron and Jerusalem.

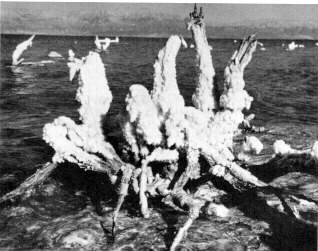

The Jordan River, formed by a union of streams from the watersheds of Mount Hermon, flows southward in a huge geological rift or fault called in Arabic the Ghôr ("the valley"). The rift begins in Lebanon and extends into the Red Sea at the Gulf of Aqabah and into Africa. From Mount Hermon the Jordan flows into Lake Huleh, a warm, swampy area of reeds and papyrus, 229 feet above sea level.4 From Huleh the waters descend rapidly for ten miles to the Sea of Chinnereth (Num. 34:11; Josh. 13:27) or Chinneroth (Josh. 11:2, 12:3; I Kings 15:20),5 a sparkling, fresh water lake 695 feet below sea level. From the lake the river meanders and twists through a jungle of tamarisk, oleander, and other shrubs (cf. Jer. 12:5) to enter the Salt Sea6 sixty-five miles to the south at 1,285 feet below sea level, the lowest exposed spot on the face of the earth. Here the waters are trapped, escaping only by evaporation and leaving a sterile, heavily saline body of water, useful in ancient times as a source of salt (Ezek. 47: 11) and for the tars that floated to its surface.7 South of the sea, the land begins a gradual rise to a height of 656 feet above sea level midway to the Gulf of Aqabah. This area, known as Wadi el Arabah (the valley of the desert), contained valuable mineral resources.

The high plateau of the Transjordan area is cut horizontally by four streams. The northern river, the Yarmuk (not mentioned in the Bible) , forms the southern boundary of the fertile tableland of Bashan, an area famous for cattle (Ps. 22:12, Amos 4:1) and timber (Isa. 2:13, Ezek. 27:6). The hill country of Gilead, stretching from the Yarmuk to a line just south of the Jabbok (Nahr ez-Zerga)8 was ideally suited to grape and olive culture. South and east was Ammon, which extended to the Arnon River (Wadi Mojib), and between the Arnon and the brook Zered (Wadi el-Hesa) was Moab. The broad tableland in these two areas was most suited to raising sheep, but could produce food crops (cf. Ruth 1:1) . Further south was Edom, a semi-desert region through which ran important trade routes. Below Edom was the land of Midian and the Arabian Desert.

SALT CRYSTALS AT THE SALT (DEAD) SEA. Driftwood that floats down the Jordan River and into the Dead Sea soon becomes coated with salt crystals. The sea waters are the densest in the world (25 per cent solids) and contain chlorides of sodium, potassium, magnesium and calcium, as well as other minerals. The high salinity imparts to the waters an oiliness that can be felt and seen. The waters in the photograph reveal something of their oily nature.

Four major trade routes crossed through Palestine from north to south, linked by a cross hatch of minor roads. One, coming down out of Syria and following the coastline, was joined by a second road from the north, which, having followed the Litani River for a distance, skirted the base of Mount Carmel and cut through the Carmel range below Megiddo to join the coast road below Joppa. A third followed the same inland route from the north but went south from the Sea of Chinnereth to link Shechem, Jerusalem, Hebron and Beer-sheba with southern roads leading to Egypt or the Gulf of Aqabah. The Transjordan highway came from Damascus and passed through key cities of Baslian, Gilead, Ammon, Moab and Edom, to the Gulf of Aqabah and then followed the eastern side of the gulf, along the coast of Arabia to the Arabian Peninsula. The portion of this road linking Damascus and Aqabah was called "The King’s Highway" in the Bible (Num. 20:17, 21:22) and was protected by a line of forts.

Water is and was the key to life and survival in Palestine. During the rainless summers, the land dries up and the hills become sere and brown. The winter rains, which come in isolated storms, bring life to the land, flooding the wadis, or stream beds which are ordinarily dry, with torrents of rushing water. The midpoint of the rainy season is January, and the early and late rains mentioned in the Bible refer to showers coming in October and November and in April. Abundance of rain meant good crops, good pasture and good life. In normally and areas and during periods of little rainfall, the hoarding of water in catch basins and cisterns made existence possible. Moisture absorbed into the subsoil of the hills penetrated until reaching a hard pan of rock, and the collected waters flowed out on the lower hillsides as springs. Subsurface pools and streams were tapped by wells. Because herbage dried up in summer, pasturage for flocks was sought in the highlands, making part of the population mobile. Cities, built near springs and wells, were in dire straits when these failed.

Palestine’s geographical divisions extended northward into Syria. Here, the coastal region became a narrow strip broken by rocky spurs projecting from the Lebanon mountains, which rise abruptly from the seaboard to heights of 10,000 feet. On these mountains grew the famous cedars, prized for building throughout the Near East.9 To the east is the broad valley of Beqa’a through which the Orontes and Leontes Rivers flow before turning westward to the Mediterranean, and on the eastern edge of Beqa’a is the Anti-Lebanon range, of which Mount Hermon10 (9,000 feet) forms the southern spur. As part of the land bridge linking Africa and Asia, Syria, like Palestine, felt the impact of foreign powers.11 The coastal road, linking important ports, was supplemented by an inland route that followed the rivers through Beqa’a.

Far to the north, the huge peninsula Anatolia or Asia Minor jutted out from the mainland toward Greece, separated by the Black Sea from the cultures inhabiting the European steppes and river basins. The southwest coastal region facing upon the Aegean, with arable lands and forested hill country, became the home of the Lydians. The center of the peninsula is a vast, rocky, mountainous wasteland with few arable areas along river valleys. In this forbidding region the powerful Hittite nation was located. The mountains of Anatolia extend eastward toward the Caspian Sea to form the arc-shaped Taurus and Anti-Taurus ranges.

In the inland highlands of Armenia, the Euphrates begins, flowing westward as if to enter Hittite domain, then south to Aram, and finally southeast to form a boundary of the Arabian desert and enter the Persian Gulf. In the half-circle of the middle Euphrates, where numerous streams pour down from the hills to increase the river’s flow, the Hurrians settled,12 the Mitanni kingdom was established,13 and the city of Haran where Abraham lived and where his father died (Gen. 11:31, 32), was located. The waters move more slowly as they approach lower Mesopotamia, and where they pour into the Persian Gulf huge deposits of alluvial soil have accumulated.

CEDARS OF LEBANON. Cedars were prized as building material, particularly important for massive pillars and for interior finishings, and were exported from Syria to all parts of the ancient Near East. They still grow near the area where David and Solomon obtained cedars for the royal buildings, and are the most magnificent trees grown in Syria.

The Tigris River, to the east, begins in the mountains of Armenia and, fed by numerous tributaries, moves toward the southeast to join the Euphrates and empty into the Persian Gulf. The area between the Tigris and Euphrates was called by the Greeks "Mesopotamia" ("between the rivers") . In ancient times, lower river regions appear to have consisted largely of marsh and lagoons with islands of solid earth upon which the earliest human settlements were founded. In the area between the rivers, the mighty kingdoms of Sumer, Babylon and Assyria were located. East of the Tigris, a wide grassy undulating plateau rises steadily toward the Zagros Mountains and here Persians and Elamites settled.

By drawing curved lines from the Persian Gulf through Mesopotamia and following the Euphrates to Aram, then down through Palestine, James Henry Breasted over fifty years ago sketched what he labeled "The Fertile Crescent," the relatively narrow belt of arable land skirting the desert. Merchants and armies traversed this route that linked Mesopotamia to the north, the west, and the south (Egypt), and as they passed through Palestine, they brought this little country into direct relationships with her neighbors.

Egypt was the only great power to threaten the southern border of Palestine. Although the nation was centered in the Nile valley and delta, called the "blackland" to contrast it with the "red land" of the desert, territorial control included the rugged hinterland of the Sinai peninsula where valuable turquoise and mineral deposits were located and through which ran roads linking Egypt by land to Mesopotamia and Asia Minor. Egypt’s northern borders were at the Wadi el Arish, the Brook of Egypt (Num. 34:5; I Kings 8:65; II Kings 24:7).14 Egypt proper, the long strip of black soil along the two banks of the Nile stretching from the first cataract to the Mediterranean, was the result of the political union of Lower Egypt (the delta) and Upper Egypt (the area from the delta to the first cataract).15 Steep cliffs and barren land separated the fertile region and the people of the second and third cataracts from Egypt, and forbidding deserts limited communication from east and west to caravan trade.

Consequently, Egyptian commerce flowed northward with the Nile toward the delta where, by land and sea, the nation was in touch with the outer world. Egyptian agricultural economy depended upon the annual rise and fall of the Nile. This mighty river, originating 2,000 miles southward near the equator in the Mountains of the Moon, was channeled to irrigate fields along its banks. When its flow, swollen by equatorial rains, swept down to inundate the land, there was promise of good crops and a bountiful year. Overabundance of water destroyed canals and dams; too little water meant famine. The river, together with the other dominant natural feature related to agriculture, the sun, held an important place in Egyptian religion.

Endnotes

- For geographic and geophysical details, see Denis Baly, The Geography of the Bible (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1957). For a more general treatment, see Denis Baly, Palestine and the Bible, World Christian Books (London: Lutterworth Press, 1960) ; "Palestine, Geography of," Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible.

- Perhaps the failure of the Sidonese to come to the rescue of Laish, a possession, when the Danites attacked reflects the westward orientation of this seaport (cf. Judg. 18:28 f.) .

- For the Philistines, see below, chap. 7.

- The modern State of Israel has drained Lake Hulch and utilized the area for agriculture.

- Later called "Sea of Galilee," "Sea of Tiberias," and "Lake Gennesaret" (I Macc. 11:67).

- Best known today as the "Dead Sea," a designation not used in the Bible. In addition to "Salt Sea" (Gen. 14:3; Num. 34:12; Deut. 3:17), the waters are called "Arabah Sea" (Deut. 3:17; 4:49), and "Eastern Sea" (Ezek. 47:18; Joel 2:20; Zech. 14:8).

- P. C. Hammond, "The Nabataean Bitumin Industry at the Dead Sea," The Biblical Archaeologist, XXII (1959),40-48.

- River names in parentheses are modern Arabic labels.

- Cf. II Sam. 5:11, 7:2, 7; I Kings 5-7.

- For other designations, see Deut. 3:9; 4:48; Judg. 3:3.

- Inscriptions on the Dog River, north of Beirut, by Egyptians, Hittites, Babylonians, Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, Romans, etc., provide an impressive summary of the country’s international relationships.

- For the relationship of the Hurrians to Horites and Hittites, cf. John Bright, op. cit., pp. 53 ff.

- For the Mitanni, cf. John Bright, op. cit., pp. 99 ff.

- Other references to this border label it "The River Egypt" (Gen. 15:12; Judith 1:9), and "Shihor" Josh. 13:3; I Chron. 13:5) which may refer to the same stream. The "Brook of the Arabah" of Amos 6:14, may be another designation or may indicate a separate valley.

- Cf. John A. Wilson, The Burden of Egypt (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1951), chap. 1; also in a paper-bound edition titled: The Culture of Ancient Egypt, Phoenix Books (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956) ; Walter A. Fairservis, The Ancient Kingdoms of the Nile, A Mentor Book (New York: New American Library of World Literature, 1962) , chap. 1.

Old Testament Life and Literature is copyright © 1968, 1997 by Gerald A. Larue. All rights reserved.

The electronic version is copyright © 1997 by Internet Infidels with the written permission of Gerald A. Larue.