Old Testament Life and Literature (1968)

Gerald A. Larue

Chapter 30 – The Hasmonean Dynasty1

Read I Macc. Chs. 14-16

WITH Simon (141-135) a new era dawned for the Jews, and for the first time since the Babylonian conquest, they breathed the pure air of freedom. The atmosphere was charged with expectation. Simon seized the important port city of Gaza, providing Judah with a direct outlet to the Mediterranean world. Treaties were made with Rome and Sparta. Jewish coins were struck. Trade and industry increased and the arts were encouraged. A pro-Hellenistic, aristocratic, priestly group, later to be called the Sadducees, began to take form. The Hasidim tended to merge with other nationalists to become the nucleus of the religio-political party later called Pharisees.

In 138, Antiochus VII Sidetes was crowned king of Syria and attacked Judah, only to be soundly defeated near Modin by Jewish troops led by Simon’s brothers, Judah and John. Three years later Ptolemy, Simon’s son-in-law, murdered Simon and Judah and one of Simon’s sons. John, later to be called Hyrcanus, rushed to Jerusalem and claimed the posts of governor and high priest. Antiochus VII seized this moment of internal disorder to attack Jerusalem. After a siege he won promises of large tribute payments, but when Antiochus was killed in 128 and Demetrius II Nicator once again became king of Syria, John Hyrcanus stopped payments to the Seleucids.

Under John Hyrcanus (135-105), Judaean territory was increased by the annexation of Idumea, Samaria and Perea. The Samaritan temple on Mount Gerizim, long an irritation to the Jews, was demolished. The Idumeans, descendants of the Edomites who had entered Judah in the early post-Exilic period, were compelled to become Jews and accept circumcision and obedience to the Torah. During Hyrcanus’ reign, the characters of the Sadducee and Pharisee parties became clearly defined, and another group called the Essenes was formed.2

The Pharisees, whose name may have meant "separatists," were a group of religious lay leaders committed to the purification of Judaism through meticulous observance of moral and ceremonial laws. They supported the temple cult but were most uneasy about the usurpation of the high priesthood by one of non-priestly caste. More often they were identified with synagogues, the local autonomous gathering places of the masses, where prayer and study were conducted. In addition to the study of the scriptures, the Pharisees emphasized the teachings of the elders or oral tradition as a guide to religion. They professed belief in the resurrection of the body and in a future world where rewards and punishments were meted out according to man’s behavior in this life. They believed in angels through whom revelations could come, and later were to develop a belief in a Messiah.3 They tended to view alliances with foreigners with suspicion.

The Sadducees were pro-Greek, aristocratic priests, whose interests were centered in the temple and the cultic rites. Their name was probably derived from Zadok, the famous priest of the time of David and Solomon (II Sam. 8:17;. 15:24; I Kings 1:34). Because the offices of high priest and governor were combined, the Sadducees tended to be deeply involved in high-level politics. Politically, they were committed to independence and to the concept of the theocratic state, as were most Jews. Although they were opposed to foreign domination, they did not object to the introduction of foreign elements into Jewish life. Like the Pharisees, they stressed the importance of observance of the Torah, but they rejected the authority of oral tradition. When confronted by situations not covered in the Torah, they enacted new laws. They rejected the Pharisaic doctrine of a resurrection and a future life and held to the older Jewish belief in Sheol. Nor did they accept the belief in angels.

The Essenes may have developed as early as the reign of Jonathan as a group of pious Jews within the Hasidim.4 The derivation of their name is not at all clear, and it may mean "the pious ones" or "the holy ones."5 For some unknown reason, they felt compelled to withdraw to the wilderness area on the shores of the Dead Sea, perhaps to mark their separation from the Pharisees.

AN OVERVIEW OF THE RUINS OF QUMRAN. The Qumran community was situated on a terrace above the ravine known as the Wadi Qumran overlooking the Dead Sea which can be seen in the background. The photograph was taken from one of the caves in which scrolls were found.

AN OVERVIEW OF THE RUINS OF QUMRAN. The Qumran community was situated on a terrace above the ravine known as the Wadi Qumran overlooking the Dead Sea which can be seen in the background. The photograph was taken from one of the caves in which scrolls were found.

The discovery and excavation of a Jewish religious communal center dating from this period at Qumran, and the recovery of numerous scrolls and thousands of fragments of manuscripts in caves nearby, have led many scholars to make some identification of the Essenes and the Qumran sect, despite the fact that nowhere in the Qumran literature is the sect identified as "Essene."6 The scroll materials are from several different centuries and therefore may represent the evolving concepts of the wilderness community. The group appears to have been motivated in part by the expectation of the kingdom of God and in part by the belief that they had been, or were being, misled and betrayed by temple authorities. They withdrew to the desert to prepare God’s way in fulfillment of Isaiah 40, to live in accordance with their understanding of the Torah, and to fulfill the ethical ideals of the prophets. The proper or right way to live was expounded by a "Right Teacher" or "Teacher of Righteousness"-an unknown person. Righteousness was best achieved in a community of those committed to the right way, composed of persons who yielded up private possessions to the community and were formally initiated into the sect. The group was structured with officers and varied ranks. In the wilderness setting they awaited the end of time and the final battle between the Sons of Light and the Sons of Darkness, which could culminate in victory and appropriate rewards for the righteous.

John Hyrcanus had planned that, upon his death, his wife would take charge of civil affairs, and his son, Judas Aristobulus, would be high priest. When Hyrcanus died in 104, Judas imprisoned his mother and all other members of his family except his brother Antigonus. Judas Aristobulus had himself crowned king, taking the title Aristobulus I. In the single year (104) that he reigned, he seized the Galilee region for Judah and compelled the inhabitants, many of whom were of Syrian and Greek descent, to become Jews. His brother Antigonus was murdered, and his mother died of starvation in prison.

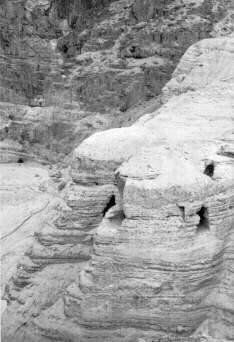

THE APERTURES OF CAVE FOUR AT QUMRAN. This cave lies below the southern edge of the terrace on which the Qumran community lived and overlooks the Wadi Qumran which can be seen at the left. A large collection of manuscript fragments were found in this cave.

THE APERTURES OF CAVE FOUR AT QUMRAN. This cave lies below the southern edge of the terrace on which the Qumran community lived and overlooks the Wadi Qumran which can be seen at the left. A large collection of manuscript fragments were found in this cave.

Jonathan, a brother of Aristobulus who had survived imprisonment, took control of Judah, Hellenizing his name to Alexander Janneus. During his relatively long reign (104-78), the Hasmonean kingdom reached its peak of territorial power, for Janneus expanded the borders. As a despotic Sadducee, Janneus waged open war against the Pharisees. They publicly objected to his mockery of certain rituals and to what the Pharisces considered to be degrading acts. In savage retaliation, Janneus released his mercenaries on the Pharisees and about 6,000 were slaughtered. The result was civil war with numerous battles, and Janneus was not always victor. The Pharisees appealed for aid to the king of Syria, Demetrius III, a descendant of the ancient enemy of the Jews, Antiochus IV. This was an error, for after the defeat of Janneus, many Jews sympathetic to the revolt balked at the thought of Syrian control and joined Janneus’ forces. Janneus smothered the revolt and exacted a gruesome revenge in the crucifixion of 800 of his fellow countrymen and the murder of many of their families before them as they hung dying on the crosses.7

A NABATAEAN TOMB CARVED INTO THE LIVING ROCK AT PETRA. Nabataean structures feature rather simple ornamentation using straight lines and the stair-like pattern that can be seen at the top of the facade. Later, under Roman influence, highly decorative patterns were introduced. The rock out of which the tomb is cut is Nubian sandstone with multicolored striations in pinks, reds and blues. Within, the tombs are rather spacious rooms in which rituals associated with the cult of the dead were performed.

A NABATAEAN TOMB CARVED INTO THE LIVING ROCK AT PETRA. Nabataean structures feature rather simple ornamentation using straight lines and the stair-like pattern that can be seen at the top of the facade. Later, under Roman influence, highly decorative patterns were introduced. The rock out of which the tomb is cut is Nubian sandstone with multicolored striations in pinks, reds and blues. Within, the tombs are rather spacious rooms in which rituals associated with the cult of the dead were performed.

Janneus died in 78 and the throne was bequeathed to his widow, Salome, who had taken the Greek name Alexandra, and she became the second woman to rule the Jews (78-69). One son, Hyrcanus, was appointed high priest and another, Aristobulus, was left as a disgruntled, potential ruler. Alexandra was pro-Pharisee and released political prisoners who immediately began a retaliatory persecution of the Sadducees which soon got out of control. Alexandra favored a positive Pharisaism with reform without revenge, improvement of the administration and law courts and the introduction of a program of elementary education. Leading scholars from Alexandria, Egypt, were invited to Jerusalem to aid in the educational program. When the aging queen fell ill and it appeared that the mild-mannered Hyrcanus might be elevated to the throne, Aristobulus raised an army. He was about to attack Jerusalem when Alexandra died. Hyrcanus was defeated at Jericho and retired as king and high priest. Upon the advice of an Idumean official named Antipater, Hyrcanus took refuge with Aretas III, King of the Nabataeans. At this same time Syria became a Roman province.

Whatever success Aristobulus II (69-63), the pro-Sadducce king and high priest, might have had in government was marred by civil war. Hyrcanus, urged on by the Idumean Antipater and backed by King Aretas, besieged Jerusalem. In 65, the Roman general Scaurus went to Syria as a legate of Pompey, and both Hyrcanus and Aristobulus appealed to him for aid. Scaurus, amply bribed by Aristobulus, ordered Hyrcanus to lift the siege, and as the Nabataean troops withdrew, they were set upon from the rear and defeated by Aristobulus.

The victorious Aristobulus returned to Jerusalem and began a series of attacks on neighboring provinces. But the people were weary of him and his brother. When Pompey arrived in Syria in 64, several delegations of Jews appealed to him, representing Hyrcanus II, Aristobulus II, and a pro-Pharisee group seeking a theocratic government under the high priest. Pompey called for cessation of all hostilities, and when Aristobulus failed to obey, Pompey marched on Jerusalem. Aristobulus was taken prisoner and shipped to Rome. Hyrcanus was appointed high priest and ethnarch. Judah was reduced in size, losing all territories acquired since Simon’s time, and was annexed to Rome as a part of the province of Syria, governed by Scaurus. Antipater was given charge of political relationships and served as a Roman puppet. The Jewish kingdom had ended. The Roman province of Judaea was born.

LITERATURE OF THE PERIOD

In addition to the dramatic historical document, I Maccabees, the literature of the late Hasmonean period consists of documents written in the name of former heroes or well-known figures, including Jeremiah and his scribe Baruch, Daniel, Esther, Solomon and a theologized version of some of the events included in I Maccabees. II Esdras, often called IV Esdras or Ezra, was written in the name of Ezra in the Christian era. The writings will be discussed in chronological sequence.

BARUCH

The work entitled Baruch is one of several writings attributed to Jeremiah’s scribe.8 The book can be divided into two major sections, one in prose, the other in poetry. Within this broad division, smaller independent units have been recognized. For analytical study, we divide the book as follows:

I. The Prose Section: Chapters 1:1-3:8.

a. 1:1-1 4, the introduction, which sets the book in Babylon in 586. Baruch reads his text before Jeconiah (Jehoiachin) and seeks funds to purchase offerings for the altar in Jerusalem.

b. 1:15-3:8, the confession of sin.

15-2:10, the recognition that Judah’s sin caused the Exile.

2:11-35, a prayer for forgiveness.

3:1-8, a plea for divine mercy.

II. The Poetic Section, Chapters 3:9-5:9.

a. 3:9-4:4, a poem in praise of wisdom.

b. 4:5-5:9, a poem of comfort for Jerusalem.

Read Baruch 1:1-14

The introductory section contradicts one bit of evidence found in Jeremiah and repeats one error from the book of Daniel. In 1:1, it is stated that Baruch was in Babylon after the destruction of the temple, but Jeremiah 43:6-7 indicates that Baruch accompanied Jeremiah to Egypt, making it impossible for the scribe to be with the Babylonian exiles in 586. Baruch 1:11 borrows incorrect information from Daniel 5:4-19 and reports that Belshazzar was the son of Nebuchadrezzar rather than of Nabonidus and this evidence enables us to date the collected work after 165, and to suggest that the editor was not Baruch but a Palestinian Jew. The editor interprets Jeremiah’s recommendation to the exiles to seek the welfare of Babylon (Jer. 29:7) as a request to pray for Nebuchadrezzar (1:11).

Read Baruch 1:15-3:8

Like other confessions, the prayer reviews past history and recognizes that disobedience to the divine will results in punishment. Dependency on Daniel 9:4-9 can be seen in 1:15-20; 2:1 f., 7-14, 16-19, indicating that this section also comes from the post-Daniel period.

Read Baruch 3:9-4:4

The first poem praises wisdom and appears to be the product of a member of a wisdom school. Possibly the writer is familiar with Job 28 (cf. 3:29-34), Prov. 8 and the work of Ben Sira, Chapter 24 (cf. 3:35-37, 4:1). For this writer, the way of wisdom is the way of peace (3:13), and wisdom is to be understood as the Law (4:1). At one moment the author glories in the transcendent majesty of God, whose house is the whole world (3:24 ff.), and at the next expresses particularism in his gratitude for Israel’s election and intimate knowledge of "what is pleasing to God" (4:4).

Read Baruch 4:5-5:9

The closing poem of lamentation defies precise dating but appears to have drawn inspiration from Deutero-Isaiah. Because 5:5-9 is a parallel to Chapter 11 of the Psalms of Solomon, a very late work which is preserved in the Pseudepigrapha, some scholars have dated this portion of Baruch in the Christian era, after the destruction of the temple in A.D. 70.9 It is possible to argue just the opposite and to maintain that this parallel is irrelevant for dating because Chapter 11 of the Psalms of Solomon was based on Baruch. We have accepted the latter position. How early the poem in Baruch may be cannot be determined, except to say that it is post-Exilic. The poem looks to the glorification of Israel, the gathering of the scattered people and a period of blessing.

It would appear that in the Hasmonean period Baruch was edited by a Jew of Palestine who, through this composite document, set before his readers his convictions about the importance of repentance, the significance of wisdom and the Law and his hope for a peaceful future. Baruch has canonical status in the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches.

THE LETTER OF JEREMIAH

This one-chapter document is affixed to Baruch as Chapter 7 in the Roman Catholic Bible, where it is given canonical status, but appears in the Apocrypha of the Protestants and Jews as a separate writing and is considered non-canonical. It purports to be a letter written by Jeremiah to the exiles in Babylon. Probably it is a post-Exilic document by an unknown writer.

The "letter" has two parts: verses 1-7 are an introduction, and verses 8-73 are a series of brief statements that terminate with the phrase "they are not gods, do not fear them" (vss. 16, 23, 29) or its equivalent (vss. 40, 44, 49, 52, 56, 69). Some effort is made to provide a Babylonian setting by references to a processional (vss. 4, 26) and cultic prostitution (vs. 43), but the procession seems to echo Isaiah 46:1-2, and the condemnation of idolatry echoes Isaiah 44:9-20. The "letter" appears to be a rather impassioned homily on the evils of idolatry.

Some indication of the time of writing may be found in the reference to seven generations of Exilic life, which would provide a date shortly after the time of Alexander the Great. We have followed R. H. Pfeiffer and placed the document in the Hasmonean period10 and recognize it as part of a developing tendency to demonstrate the superiority of Judaism by attacking and denigrating other religions. The author delivers his mocking taunts, ignoring the basis upon which the ritual of the other faith might have rested (vs. 33), and insisting that the image was believed to be the actual god rather than a symbol. The effect of his scathing attack is to portray the beliefs and rites he dislikes as stupid and ridiculous.

ADDITIONS TO ESTHER

The LXX version of Esther is much larger than the Hebrew edition, and the so-called additions of the Apocrypha represent the extra material. In Roman Catholic Bibles most of these additional verses have been gathered together as separate chapters (chs. 11-16) and appended to the shorter version of Esther. Actually, the additions were designed to fit into the text of Esther at specific places, as the notes in the Revised Standard Version of the Apocrypha indicate.

It is generally accepted that the shorter Hebrew version is earliest and that the additions were composed later to transform the secular book of Esther into a religious document by introducing passages affirming belief in and dependency on God. At times, the extra passages contradict or correct material in Esther. We will follow the Roman Catholic numbering of these extra chapters as they appear in the Revised Standard Version. As each section is studied, it will be wise to refer to the text of Esther to assist in grasping the context.

Read Chs. 11:2-12:6

The first addition was placed at the opening of the story of Esther to introduce Mordecai. He is said to have been exiled with Jehoiachin (Jeconiah) in the first deportation. In the addition we are told that he discovered the plot against the king in the second year of Artaxerxes’ reign (11:2), rather than in the seventh year (Esther 2:16-21). The remarkable dream is not explained until the end of the story.

Read Chs. 13:1-7

The next section is designed for insertion between 3:13 and 3:14 in the older text of Esther. By quoting what appears to be an official document, it brings to the story a touch of authenticity and historicity. The document changes the day for the proposed annihilation of the Jews to Adar 14 (13:6) rather than Adar 13 (3:13).

Read Chs. 13:8-15:11

Chapters 13:8-15:11 are to be read between Esther 5:2 and 5:3 and explain Mordecai’s refusal to bow before Haman as the act of a pious Jew who, like Daniel, will bow only to God. Esther, too, is transformed into a pious woman who pours out her inmost feelings before God in an act of abject humility. We learn that her role in the royal harem is distasteful to her and that she has abstained from participation in pagan rites (14:15-18). She is made to appear more like Judith as the heroic aspects of her role are enhanced and her actions become almost sacrificial.

Read Ch. 16

The letter of Artaxerxes correcting his previous edict is to be read after Esther 8:12. The author of this addition transforms Haman into a Greek (16:10), whereas previously he was an Amalakite (Agagite), and states that like other Greeks he lacked "kindliness" and could not be trusted, for he was willing to betray his benefactors. Artaxerxes’ high praise for the Jews honors Jewish law and religion. The 13th of Adar is set aside as a day of rejoicing, preceding what almost became doomsday.

Read Ch. 10:4-13

The epilogue follows Esther 10:3, explains the dream in the prologue, and presents the election idea in a different form. Here, perhaps some clue is given to the time when the additions were composed. Verses 10:8 ff. suggest that the "nations" that would have destroyed the Jews have failed, that the Jews have been saved, and that God has done great things for them. Such an attitude fits best into the period of Jewish independence-perhaps during the time of Simon (141-135).

Read Ch. 11

The concluding sentence is a translator’s note giving the time when Esther was translated into Greek together with the additions. The "reign of Ptolemy and Cleopatra" is not a very precise clue, for several Ptolemys were married to Cleopatras: Ptolemy V (203-181), Ptolemy VI (181-145), Ptolemy VIII (116-108, 88-80), Ptolemy XII (80-58, 55-51) and Ptolemy XIV (51-44). The reign of Ptolemy VIII may be the time when the translation was made.

THE ADDITIONS TO DANIEL

During the second century several independent units were composed as additions to the story of Daniel. One of these, "The Story of Susanna," appears as an introduction to the Book of Daniel in some manuscripts, possibly placed there because Daniel appears to be very young in the story. In other manuscripts, it is added as Chapter 13. "The Prayer of Azariah" and the "Song of the Three. Young Men" were designed for insertion at appropriate spots in Chapter 3 of Daniel, but in some manuscripts they follow the story of Susanna to form Chapter 14. There are no positive clues for dating in these stories, but they must have been composed between the time Daniel was written (165) and the period when it is believed that the book was made part of the LXX (about 100).11

THE PRAYER OF AZARIAH AND THE SONG OF THE THREE YOUNG MEN

Read the "Prayer" and the "Song"

The two poems and their prose explanations were written for insertion between Daniel 3:23 and 3:24. The Prayer has nothing to do with the plight of the young men in the fiery furnace. It is a communal lamentation, perhaps composed during the early years of the Maccabean period before Judas had rededicated the temple (cf. vs. 15). The poem acknowledges God’s justice in bringing the nation into the desperate situation, but calls to remembrance the covenant and traditions of the past and pledges fidelity to God. Verses 15 and 16 recall Micah’s definition of true religion (Micah 6:6-8).

In the Song of the Three Young Men, the plight of the heroes is ignored, except for Verse 66. The song is a hymn of praise modeled on Psalm 148, perhaps written originally for antiphonal chanting and adapted through Verse 66 to its present setting.

Apparently someone decided that the three young men in the furnace ought to do something other than walk around in the flames, and two poems, taken from other contexts, were added. Or perhaps someone believed that martyrs ought to pray, rejoice and witness to their faith. The Eastern Orthodox Church accepts these writings as canonical.

THE STORIES OF SUSANNA, AND BEL AND THE DRAGON

Read Susanna

These three stories are among the earliest known "detective stories." Susanna employs the familiar motif of a woman falsely accused and rescued by a wise judge. In refusing to yield to the desires of the two lecherous elders and in maintaining her innocence despite threat of death, Susanna sets an example of ethical standards expected of a married woman. As the prosecutor, Daniel demonstrates the weakness of Deut. 17:6 and exhibits the need for intensive and careful cross-examination of witnesses to prevent collusion.

Read Bel and the Dragon

The unmasking of the idol, Bel, and the destruction of the dragon, are tales designed to demonstrate the superiority of the Jewish religion by displaying the weaknesses in other faiths. Rather than announce that the priests of Bel practiced deceit as the writer of "The Letter of Jeremiah" did, this author prefers to use fiction to expose their nefarious practices. Scattering ashes to record footprints is a technique often found in fairy tales.

The story of the defeat of the dragon may contain reminiscences of the Babylonian creation myth and the defeat of Tiamat, the dragon symbol of chaos. Daniel’s return to the den of lions is enlivened by the story of the miraculous delivery of food by the prophet Habakkuk. Only Bel and the Dragon are accepted as canonical, and only by the Eastern Orthodox Church.

THE PRAYER OF MANASSEH

Read II Chron. 33:11-19 and Manasseh’s Prayer

The prayer of Manasseh is a non-canonical, penitential psalm extolling the majesty and glory and forgiving nature of God. It begins with praise of God’s creative power (vss. 1-5) and forgiving mercy (vss. 6-8), continues with a general confession of sin (vss. 9-12) and an appeal for forgiveness (vss. 13-14), and concludes with a vow and a doxology (vs. 15). The psalm suggests that the author was a Jew familiar with the LXX. The earliest literary evidence of the psalm is in a Christian writing of the second or third century A.D., the "Didascalia," and in relatively late editions of the LXX (fifth to tenth centuries). Some scholars have attributed it to a Christian writer, but it betrays no peculiarly Christian emphases. It can be fitted nicely into the post-Exilic Hasmonean period when documents were being composed in the name of historical figures. Only the title links the prayer to Manasseh, probably on the basis of Manasseh’s repentance as reported in II Chron. 33:11 ff.

I MACCABEES

We read I Maccabees previously as we developed the history of events of the Maccabean period; therefore, in analyzing the book it will only be necessary to consult specific passages for reference. I Maccabees relates the thrilling story of the revolt against the tyrannical efforts of Antiochus IV to Hellenize the Jews and records the ultimate establishment of an independent state. The account begins with Alexander the Great and ends with John Hyrcanus. The history is developed chronologically as the outline indicates:

1:1-9, a summary of Alexander’s conquests and the acts of the Diodochoi.

1:10-64, the persecution of the Jews by Antiochus IV Epiphanes.

2:1-70, the story of Mattathias and the Jewish revolt.

3:1-9:22, the feats of Judas, the Maccabee.

9:23-12:53, Jonathan’s leadership.

13:1-16:24, Simon’s leadership.

The book is the work of an unknown Palestinian Jewish patriot who wrote during the latter part of John Hyrcanus’ rule or just after his death (104).12 Perhaps the author viewed his work as an extension of the history of the Chronicler for like the Chronicler, he used genealogies (2:1; 14:29), gave the speeches of key persons, inserted poems and referred to official documents. He is well versed in Hebrew scriptures and knows the events of the period and the terrain of Palestine. Despite his efforts to be accurate, he is not free from error, for he stated that before Alexander died he divided his empire among the Diodochoi (1:6). The speeches composed for Judas (3:58-60; 4:8-11, 16-18, 30-33) and Mattathias (2:7-13) and others may have some basis in reminiscences, but they should be treated as artificial, written in the tradition of Hellenistic writers of the period. The poems include dirges, laments and hymns of praise and may rest on a tradition of real events, but they may equally well be the composition of the author of I Maccabees (cf. 1:24-28, 36-40; 2:7-13; 3:3-9). The reported diplomatic documents and official letters may have been drawn from such official archives as "The chronicles of the high priesthood" (16:24) or copied from such inscriptions as the bronze memorial tablets (14:18, 27)13 and so represent official wording. They could equally well be semi-authentic reconstructions in the writer’s own words. The simplicity of style and the general reliability of the record tend to convey an impression of historical accuracy. In the absence of other confirming or contradicting evidence, I Maccabees must be treated seriously.

The author was a religious Jew and the scriptural allusions as well as the speech attributed to Mattathias recalling the heroes of the past reveal familiarity with sacred traditions. He does not attribute victories to any intrusion or direct act by God (cf. 3:58-60; 13:3-6), but in the speeches of the Jewish leaders and through their responses portrays God acting through natural means. He avoids direct references to God, preferring to speak of the people blessing "Heaven" (4:55), or to say that Judas prayed to the "Savior of Israel" (4:30). Attempts to demonstrate Pharisaic or Sadducean leanings have been inconclusive, and one can only note that the writer, as a man of faith, viewed Israel as a holy congregation, a people separated from and in opposition to the outside world because of their religious heritage and particularistic relationship to the universal God.

II MACCABEES

II Maccabees is an abridged account of the Maccabean revolt based on a five-volume work by Jason of Cyrene (2:19-23).14 The larger work has disappeared, and nothing beyond this one reference is known of Jason. The extent to which the editor of the abridged version imposed his own point of view on the work of Jason is a matter of debate,15 but there is no valid reason for denying that the bulk of the summarized work is Jason’s. The two letters appended at the beginning of II Maccabees, which urge the Egyptian Jews to observe Hanukkah, are not by Jason, nor are the editorial introduction (2:19-32) and the admonition to the reader, which is written in the first person (6:12-17), nor, perhaps, the side comment in 4:17. The rest of the work, we believe, fairly represents Jason. Most scholars date Jason’s original work after the middle of the second century and the abridgment shortly before the close of the Hasmonean period. Jason probably wrote in Alexandria, Egypt.

The purpose of the abridgment was to present a succinct outline of the struggle for independence (2:24-32), and perhaps also to reassure the reader that the afflictions suffered by the Jews were permitted by God for disciplinary reasons (6:12). Jason’s purpose must be surmised, for it is not stated explicitly. The emphasis on the centrality of the temple has led some scholars to suggest that his aim was the exaltation of this holy place. Broadly speaking, Jason appears to have been interested in reporting the Maccabean struggle in terms of sacred history. To accomplish this, he does not hesitate to explain failures and victories as acts of God, rather than of men as the author of I Maccabees does. He introduces visions, angelic figures, theological concepts, festivals, and acts of worship as significant elements of his story. He extols the supremacy of God in universalistic terms and sermonizes on the way God responds to his people when they are faithful, and how they are punished when they sin.

The book may be subdivided a number of different ways, but if 3:40, 7:42, 10:9, 13:26 and 15:37 are statements marking conclusions of Jason’s five volumes, then perhaps it is better to attempt to read II Maccabees recognizing the divisions that Jason made.

I. Correspondence with Egypt, Chapters 1:1-2:18.

a. 1:1-9, the first letter.

b. 1:10-2:18, the second letter.

II. The Abridger’s Preface, 2:19-32.

III. The Five Books of Jason, Chapters 3-15.

a. 3, the story of Heliodorus.

b. 4-7, Jewish opposition to compulsory Hellenism.

c. 8-10:9, the Maccabean revolt, the cleansing of the temple and the institution of the Feast of Dedication (Hanukkah).

d. 10:10-1 3:26, battles with Antiochus V Eupator and Lysias.

e. 14:1-15:37, the defeat of Nicanor and the institution of Nicanor’s day.

IV. The Abridger’s Appendage, Chapter 15:38-39.

Read II Macc. Chs. 1-2

The authenticity of the letters purporting to be from Palestinian Jews to Egyptian Jews has been the source of much discussion. Most scholars treat them as compositions of the epitomist,16 but it is possible that they are compilations based on older documents. The second letter contains an interesting legend about the preservation of sacred fire, which may embody two separate traditions. One account states that the fire was hidden in a cistern by priests at the time of the Exile and discovered in Nehemiah’s day. The other says that Jeremiah ordered the exiles to take the holy fire, and that the prophet concealed the tabernacle, the ark and the altar of incense in a cave. Whether there is are echo of an ancient fire festival preceding Hanukkah in these legends is not clear.

Read II Macc. Chs. 3-15

In the idealization of the high priesthood of Onias, Jason claimed that the temple was enriched by gifts from rulers of other nations and that it was this great wealth that Heliodorus sought. Perhaps he intended to demonstrate that the prophecy of Haggai had been fulfilled (Hag. 2:6 f.). The miraculous preservation of the treasure and the saving of Heliodorus’ life came through the righteousness of those who cried out to God in the proper manner.

The order of events given by Jason differs slightly from the preferred chronology of I Maccabees:

|

I Maccabees

|

II Maccabees

|

|

Judas defeats Lysias (4:26-35).

|

The death of Antiochus (9).

|

|

Judas dedicates the temple (4:36-61).

|

Judas dedicates the temple (19:1-8).

|

|

Judas battles hostile neighbors (5).

|

Judas defeats Lysias (11:1-15).

|

|

Antiochus IV dies (6:1-17).

|

Judas battles hostile neighbors (12).

|

Jason explained that the reason God failed to treat Antiochus’ violation of the temple as he had Heliodortis’ act was because the people had sinned (5:17). The treasure donated by the nations disappeared with Antiochus.

Divine forewarning of the struggle with Antiochus was given in the vision of the "golden-clad horsemen," which was improperly understood (5:1-4). The persecution of the Jews by the Hellenists echoes the horrors described in I Maccabees. Heroic Eleazar, who put faith above life, is cited as an example to every Jew. The speeches that Jason ascribes to Eleazar are homilies. The five young men who died gruesome deaths for their religious beliefs are counterparts of the heroes in Daniel, except that in the real life situation there was no miraculous deliverance.

Judas does not struggle alone in II Maccabees, and it is with God’s help that the enemy is overcome (8:24). Grateful warriors remember their religious obligations (8:27-29). Antiochus’ illness comes as a blow struck by God (9:5). Jason’s account of Antiochus’ repentance and acknowledgment of the supremacy of the Jewish deity, and the futile attempt to bargain with God, is mocking satire. The section ends in triumph with the restoration of worship in the temple and the institution of a day of remembrance (10:1-8). The defeat of Nicanor has an equally victorious conclusion and provides for the institution of Nicanor’s Day, which was later incorporated in the festival of Purim (15:36).

In addition to giving a theological interpretation of the Maccabean revolt, Jason designed his work to edify and inspire. Schooled in the rhetoric of Alexandria, Jason did not hesitate to employ exaggeration, epithets, melodramatic situations and any other literary tool that would enhance his work. The details of the profanation of the altar are subdued and the acts that defiled the temple dramatically enlarged. He wrestles with theological themes-the silence of God when his people suffer fiendish tortures, God’s failure to respond when acts of indecency were committed within the temple precincts-and discusses these matters in terms of discipline, martyrdom (7) and sin (12:40). The wicked would die an eternal death with no resurrection (7:14), but the righteous would enjoy resurrection of the body, the renewal of life to eternity (7:9-12). He believed in the efficacy of expiation rites and prayers for the dead (12:43-45) and in angels. It is not possible to label Jason a Pharisee for certain, but without doubt he accepted many of their beliefs.

I Maccabees and II Maccabees are accepted as canonical by the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches.

THE WISDOM OF SOLOMON

The Wisdom of Solomon, like Proverbs and Ecclesiastes, is composed in the name of the famous Hebrew monarch. The book was written in Greek, probably by a Jew of Alexandria who was trained in Greek rhetoric and philosophy, and whose knowledge of the LXX is apparent in his writing. The most suitable date for this work is between the beginning of the first century B.C. and the end of the Hasmonean period.

The book is an apologia of Jewish belief in God, aimed particularly at apostate Jews. It has three major parts:

- Chapters 1-5, a poetic contrast of the wise and foolish.

- Chapters 6-9, a mixture of prose and poetry addressed to kings and judges.

- Chapters 10-19, for the most part a prose meditation on wisdom and salvation-history. This section is interrupted by a discourse on folly (chs. 13-15).

Read Chs. 1-5

As a ruler Solomon addresses his peers and as a wise man instructs them, urging them to follow Yahweh to gain wisdom. Something of the style of older wisdom writing appears in the use of parallelism, but the short individual sayings have been replaced by long discourses or treatises. The writer, through Solomon, admonished those who use the arguments of Ecclesiastes concerning the meaninglessness of life to defend pleasure-seeking that includes persecution and baiting of the righteous (ch. 2). Belief in death as the end is countered by a defense of belief in the immortality of the soul (ch. 3). Like Ben Sira, the author questions the merit of large families and the sense of continuity that some expect to find in their heirs (ch. 4).

Read Chs. 6-9

The repetition of the opening address to kings marks the start of a new section. The song of praise for wisdom (ch. 6) is followed by Solomon’s explanation of his greatness as a gift of wisdom.

Read Chs. 10-19

The meditation on Hebrew history as determined by wisdom and blessed by God, demonstrates that vicissitudes of the past proved to be blessings in disguise. Some of the implications border on the fantastic (cf. 19:1-7).

The writer appears to have had several reasons for writing his treatise. He is concerned with the question of theodicy, which in his day took the form, "Why, if orthodoxy is the right way, does God not reward his own? Why are the impious in better circumstances?" The author responds to this ancient query on two levels: individual and national. Justice for the individual comes in the afterlife where the scales are balanced. So far as the nation is concerned, he argues that God has always cared for his people, but that at times it is necessary to have the perspective of history to recognize and appreciate the fact.

He desires to confront the secular Jew who represented the attitudes given in Chapter 2 and who persecuted the pious Jew perhaps in reaction to the rebukes of the righteous. These unorthodox persons are warned of the day of judgment. It is possible that in addressing his words to kings, the writer hoped to influence non-Jewish readers and the contrast between the folly of idolatry and the superiority of Jewish monotheism might have been aimed at such persons.

Like other wisdom writers, this author speaks of wisdom as a manifestation of God (7:25 f.), existing before the creation of the world (9:9 f.). God is described as the creator, but wisdom is involved in the creation process (7:22; 9:1 f.). The impact of Platonic philosophical concepts is apparent in the writer’s view of man. Man consists of a physical body and an indwelling spiritual soul (15:8). The body is a burden to the soul (9:15), and the soul is pre-existent (8:19-20). The soul is immortal (3:1-5) and after death enjoys rewards or suffers punishments. Man was robbed of the eternal life that was his at creation through the "devil’s envy" (2:24). Mankind is divided into two groups: those who are of the devil’s "party" and those who belong to God. For the first time, we encounter the devil as a personality, a power opposed to God but not identified here as Satan or any other specific angel.

The Wisdom of Solomon has canonical status in the Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches, but not among Jews and Protestants.

II ESDRAS (IV EZRA OR ESDRAS)

II Esdras, a composite apocalyptic document containing writings by Christians and Jews, was composed during the Christian era and therefore lies beyond the perimeters of Old Testament history. It is without canonical standing. Because it has been included in the Apocrypha it falls within the scope of this book and will, therefore, receive brief consideration, without any attempt being made to engage in the discussion of the historical factors that lie behind it.

The simplest outline of the book is as follows:

I. Introduction, Chapters 1-2, Christian additions.

II. The seven visions, Chapters 3-14.

a. 3:1-5:20, the first vision.

b. 5:21-6:34, the second vision.

c. 6:35-9:25, the third vision.

d. 9:26-10:59, the fourth vision.

e. 11:1-12:47, the fifth vision, the eagle.

f. 13:1-58, the sixth vision, the man from the sea.

g. 14:1-48, the seventh vision, the writing of the books.

III. Conclusion, Chapters 15-16, Christian additions.

Read Chs. 1-2

The distinctive Christian character of the introductory chapters can be discerned in the echoes of New Testament teachings. For example, the statement "I gathered you as a hen gathers her brood under her wings" is reminiscent of Matt. 23:37. Other passages revealing dependency on Christian writings include 1:32 (cf. Matt. 23:34-35); 1:35 (cf. Rom. 10:14); 1:39 (cf. Matt. 8:11).17 The people who are to receive the kingdom denied to Israel are, of course, the Christians, and the "mother" urged to embrace her children is probably "Mother Church" (2:10-32). The closing section of Chapter 2 reflects the imagery of the Revelation to John, and the "shepherd" (2:34), "Savior" (2:36) and the "Son of God" (2:47) are references to Jesus, the Messiah who is to return. No clear indication of date is discernible in these two chapters, but many scholars suggest that they were added to the visions after the middle of the second century A.D.

Read Chs. 3-14

Like Job, Ezra raises the problem of theodicy, but unlike Job, he is unwilling to accept the answer given to Job. He presses for details and they come in familiar apocalyptic garb. The initial vision is a response to Ezra’s perplexity over God’s use of unrighteous Babylon (Rome) to harass Zion-the same problem that troubled Habakkuk. God’s answer, delivered by Uriel,18 is a challenge to Ezra much like that given to Job. Ezra, like Job, admits man’s finitude, but learns that when the predestined number of the righteous has been reached, the time of judgment will come and the wicked and righteous will receive their just rewards. The time of the end, which, Ezra learned, was close at hand, is to be preceded by signs. Sin results from a "grain of evil" sown in Adam’s heart (4:30), giving to man the impulse or desire for evil (3:21).19

In the second vision, Ezra reiterates his complaint concerning the treatment of God’s people (5:21-40) and raises a new question about those who die before the end of the age has come (5:41). He learns that God planned all that occurs from before the foundation of the world and that all the righteous will be treated alike. The signs of the end of the age, like those of the first vision, are ugly and forbidding.

Israel’s role in the world to come is the subject of the third vision. Ezra learns that only Israelites will be saved and of these, only those who observe the Law. God’s son, the Messiah, is introduced as one who will reign for four hundred years and then die with all living creatures as the world returns to primeval silence (7:28 ff.). After seven days, the resurrection of the dead will occur and judgment will take place. Ezra sought more information: how long does the soul rest after death before being judged (7:75)? He learns that the souls of the righteous return immediately to God, while the souls of the wicked wander in torment up to the time of judgment when they will be destroyed. The emphasis is upon the few who will achieve salvation either by their faith or by their good works (9:7-25).

The fourth vision depicts Zion as a mourning wife bewailing the fate of her children. Suddenly the scene changes, and Ezra is permitted to get a glimpse of the new Jerusalem that will come in the future.

In the fifth vision, Rome is depicted as an eagle, the world empire that disappears when the lion, the Messiah, comes. To make Rome the fourth kingdom of Daniel’s vision, the apocalypticist is compelled to reinterpret Daniel (12:10 ff.). The Messiah is of the Davidic line (12:32). In the sixth vision, the Messiah is portrayed as a man coming out of the sea, and the tribes of Israel are gathered to him and the wicked destroyed. The contrasting views of the Messiah in the third, fifth and sixth visions illustrate the fluidity of messianic concepts in this period.

The final vision explains how the scriptures were rewritten by Ezra’s men under the guidance of God, demonstrating their divine inspiration. Ezra is instructed to make twenty-four books public, which would be the twenty-four books of the Jewish canon,20 and to reserve seventy books for the wise; these extra volumes would be the apocalyptic non-canonical writings. Perhaps, here, some clue is given to the time of writing, for the canon of the Jews was not established until A.D. 90, so that the visions would probably have been recorded after that time. Obviously, the writer is not one of those who accepted the dicta of Jamnia,21 and he does not hesitate to inform his readers that the non-canonical books contain esoteric writings not for the common people but for the elite.

Read Chs. 15-16

The Christian additions that conclude the book are often dated about the middle of the third century A.D., at the time when the Christian church was under persecution by Decius and the Roman empire was threatened by Goths, Persians and Palmyrenians. The attacks on the empire are interpreted as acts of divine retribution for harsh treatment of Christians.22

There is no way to identify the Jewish author23 of the seven visions, but he reveals a typically orthodox concept of God as creator and judge, harsh in the treatment of sinners, but merciful to his righteous ones. Sin is an act of rebellion against God that results in estrangement (6:5; 7:48) and leads to punishment. The concept of the Messiah which developed in the inter-testamental period is conveyed in two images. The man from the sea (13:25-52) is a pre-existent figure. His rule is not everlasting and little is said of him. The Messiah as the lion (7:28 ff.) is called God’s son and his reign is for four hundred years, after which he dies. There is both harmony of thought and fluidity of image in the Messiah pictures. Death and eternal life are separated by an intermediate stage, which in itself provides intimations of the final state of each individual. The remnant concept appears once again in the number of those saved. Salvation is not universal, nor for all Jews, but only for that select handful who carefully fulfill the Law.

Endnotes

- The title "Hasmonean" is derived from the great grandfather of Mattathias, according to Josephus (Antiquities 16:7:1) but it has been argued that it may designate "princes" or "dignitaries," implying that the men of this line were "princes of Israel." Cf. S. Tedesche and S. Zeitlin, The First Book of Maccabees, Appendix A, pp. 247-250.

- Information concerning these groups is drawn primarily from the works of Josephus and Philo, both Jewish writers of the first century A.D.

- The messianic belief is expressed in the Pharisaic document "The Psalms of Solomon," to be found in the Pseudepigrapha.

- Cf. Matthew Black, The Scrolls and Christian Origins (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1961), pp. 15 ff.

- Ibid., pp. 13 f.

- For a detailed discussion of this problem, cf. Millar Burrows, More Light on the Dead Sea Scrolls, pp. 263 ff.

- It is possible that many of the events of this period are reflected in statements in the literature of the Qumran community; cf. John Allegro, The Dead Sea Scrolls (Baltimore: Penguin Books, Inc., 1956), pp. 96 ff.; Burrows, More Light on the Dead Sea Scrolls, pp. 214 f.

- For others, see the Pseudepigrapha.

- Brockington, op. cit. p. 88.

- Pfeiffer, History of New Testament Times, pp. 413-417. For earlier dating, cf. Brockington, op. cit., pp. 90-92.

- Pfeiffer, History of New Testament Times, pp. 438-444.

- Josephus did not utilize the last three chapters of I Maccabees,. and it has been argued that the original work terminated with chap. 13 and that the final editing took place after the destruction of the temple in A.D. 70. Cf. Tedesche and Zeitlin, op. cit., pp. 27-33.

- Inscribed copper plaques found at Qumran indicate that such inscriptions were not uncommon. Cf. John Allegro, The Treasure of the Copper Scroll (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1960).

- Cyrene was a Greek city on the Mediterranean coast of North Africa and the capital of Cyrenaica, an independent kingdom conquered by Alexander. At this time it was under Ptolemaic control.

- Cf. Pfeiffer, History of New Testament Times, pp. 510-522.

- Pfeiffer, History of New Testament Times, pp. 506-508; S. Tedesche and S. Zeitlin, The Second Book of Maccabees, Jewish Apocryphal Series (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1954), pp. 31-40.

- For additional references, see the notations in The Oxford Annotated Apocrypha (New York: Oxford University Press, 1965), pp. 23-26.

- Uriel, whose name means "fire of God," is the fourth of the chief angels, the others being Raphael, Michael and Gabriel, whom we have encountered before. Uriel is not only a messenger but, in the pseudepigraphaic book of Enoch, is both guide and supervisor of Tartarus, the lowest section of Hades.

- The Hebrew term yetser means "impulse" and can refer to an impulse for good or an impulse for evil. The theme is developed in the Qumran document popularly called "The Manual of Discipline."

- Sitpra, Chapter 1.

- See below, Chapter 31, the section on "The Jewish Canon."

- E. J. Goodspeed, The Story of the Apocrypha (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1939), p. 111.

- The issue of single versus multiple authorship has been debated. F. C. Porter, The Messages of Apocalyptical Writers (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1905), p. 336, and H. H. Rowley, The Relevance of Apocalyptic (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1947), pp. 103, 142, are among those supporting the unity of II Esdras. G. H. Box "IV Ezra," The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament, ed. R. H. Charles (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1913), pp. 542 ff.; W. O. E. Oesterley, II Esdras (The Ezra Apocalypse), Westminster Commentaries (London: Methuen and Company, 1933), p. 148; and C. C. Torrey, The Apocryphal Literature (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1945), p. 116 are among those supporting multiple authorship.

Old Testament Life and Literature is copyright © 1968, 1997 by Gerald A. Larue. All rights reserved.

The electronic version is copyright © 1997 by Internet Infidels with the written permission of Gerald A. Larue.