Old Testament Life and Literature (1968)

Gerald A. Larue

Chapter 3 – The Analysis of the Pentateuch

PERHAPS the portion of the Bible which best demonstrates the results of the historical-literary approach is the Pentateuch.1 The five books were named by the Jews of Palestine according to the opening Hebrew words:

I. Bereshith: "in the Beginning"

II. We’elleh Shemoth: "And these are the names"

III. Wayyiqra’: "And he called"

IV. Wayyedabber: "And he spoke"

V. Elleh Haddebarim: "These are the words"

The names now used in the English translations are from the Septuagint:

I. Genesis: the beginnings of the world and of the Hebrew people

II. Exodus: departure from Egypt under Moses

III. Leviticus: legal rulings concerning sacrifice, purification, and so forth of concern to the priests, who came from the tribe of Levi

IV. Numbers (Arithmoi) : the numbering or taking census of Israelites in the desert

V. Deuteronomy: meaning "second law," because many laws found in the previous books are repeated here

These writings, which begin with the creation of the world and trace the development of the Hebrew people through the patriarchal period up to the invasion of Canaan, were believed from very early times to be the work of one person – Moses.2 There were those who questioned the Mosaic authorship. About A.D. 500 a Jewish scholar wrote in the Talmud3 that the last eight verses of Deuteronomy which tell of Moses’ death must have been written by Joshua.4 By the time of the Protestant Reformation, Roman Catholic and Protestant scholars were discussing the difficulty of maintaining the Mosaic authorship of the Torah.

Part of the problem lies in the fact that at no point in the Pentateuch is it stipulated that Moses is the author; certain portions are said to be by Moses, but not the total writing. On the other hand, there is good evidence that Moses could not have been the author. In Gen. 14:14, Abram is said to have led a group of men to the city of Dan, but elsewhere it is stated that this city did not come into existence until the time of the Judges (Judg. 18:29), long after Moses’ time. The conquest by the Gileadites of the area called Havvothjair took place in the time of the Judges (Judg. 10:3-4), yet it is reported in the Pentateuch (Num. 32:41; Dent. 3:14). The time of the Hebrew monarchy is reflected in Gen. 36:31, yet this passage is set in a discussion of the patriarchal period. How could Moses write of conditions that did not come into being until long after his death?

There is some indication that whoever wrote certain parts of the Pentateuch was in Palestine, within the territory which in Moses’ time had not yet been entered. Gen. 50:10, Num. 35:14, and Deut. 1:1, 5, 3:8, 4:46 speak of places which are located "beyond the Jordan," which is to say on the east side of the Jordan and outside of Palestine proper. Such a statement could only be uttered by someone on the western side of the Jordan river, and Moses, we are told in Deut. 34, never entered that land.

Other evidence also suggests that Moses did not write the Pentateuch, and that many different writers made contributions to it. There are contradictory statements, one of the most obvious of which concerns the number of animals Noah took into the ark. In Gen. 6:19 Noah is told to take two of every kind of living creature – one male and one female – but in Gen. 7:2 seven pair of clean animals and birds are required. Would a single writer be so inconsistent?

Num. 35:6-7 specifies that Levites were to receive certain territorial inheritances, but Deut. 18:1 makes it quite clear that they are to have no inheritance. According to Exod. 3:13-15 and Exod. 6:2-3, the personal name of God, "Yahweh,"5 was revealed for the first time to Moses on the holy mountain. Prior to this revelation, Yahweh was known only as "Elohim,"6 or as "El Shaddai."7 On the other hand, however, Gen. 4:26 indicates that from very early times men called upon God by his personal name of Yahweh, and in numerous places the patriarchs use the name Yahweh (see Gen. 22:14, 26:25, 27:20, 28:13). Would a single author make statements so contradictory? In fact, the very manner in which divine names are used prior to the revelation of Yahweh’s name in Exodus raises problems. In certain sections of Genesis "Elohim" appears exclusively (Gen. 1:1-31, 9:1-11) ; in other places "Yahweh" appears alone (Gen. 4:1-16, 11:1-9). It would appear that different traditions have been brought together.

Some stories appear more than once, in what scholars have called "doublets." For example, in Gen. 15:5 Abraham is promised many descendants, and in Gen. 17:2 the promise is needlessly repeated. In Gen. 12:11-20 Sarah pretends to be the sister of Abraham. This same story appears in a slightly different setting in Gen. 20:1-18, and is told again with Isaac and Rebekah as central actors in Gen. 26:6-11. In the last two examples, Philistine kings are mentioned and the Philistines did not settle in Palestine until the twelfth century. How are such repetitions, contradictions and anachronisms best explained?

By the seventeenth century a number of scholars had wrestled with the problems of the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch. Carlstadt, a leader of the Reformation movement in Germany, wrote a pamphlet in 1520 arguing that Moses did not write the Pentateuch, for the style of writing in the verses reporting Moses’ death (Deut. 32:5-12) was that of the preceding verses. In 1574, A. Du Maes, a Roman Catholic scholar, suggested that the Pentateuch was composed by Ezra, who used old manuscripts as a basis. Thomas Hobbes, the English philosopher, concluded in 1651 that Moses wrote only parts of Deuteronomy (Leviathan III:33). In Tractatus theologico-politicus (1677), Baruch Spinoza, the Jewish philosopher, recognized as one of the founders of modern biblical criticism, reached a conclusion much like that of Du Maes, that Ezra compiled Genesis to II Kings from documents of varying dates. Shortly afterward, Richard Simon, a Roman Catholic priest, often called "the father of biblical criticism," gathered together the substance of critical analyses up to his time and raised the problem of literary history, thus opening the door to the application of techniques used in the study of non-sacred literature to the Bible.

In the eighteenth century Jean Astruc, a celebrated physician, published a treatise on Genesis in which he postulated that Moses used two major sources in writing the book of Genesis.8 The source in which the name "Elohim" is used for God, Astruc called "A," and that which used "Yahweh" was labeled "B." Ten fragmentary sources were also recognized and given alphabetical designations. Additional criteria for defining sources were worked out by J. G. Eichorn, sometimes called "the father of Old Testament criticism"9 or, on the basis of his five volume "Introduction" to the Old Testament, "the father of the modern science of introductory studies."10

Others built upon these foundations. In 1806-7 W. M. L. DeWette, a German scholar, published a two volume introductory study of the Old Testament in which he suggested that the book found in the temple in 621 B.C., during the reign of King Josiah of Judah (II Kings 22-23), was the book of Deuteronomy. In the work of Julius Wellhausen, who built upon the research of K. H. Graf and Wilhelm Vatke, the most significant analysis of the Pentateuch was made. The thesis known as the Graf-Wellhausen theory, or as the Documentary Hypothesis, still provides the basis upon which more recent hypotheses are founded.

The Graf-Wellhausen analysis identified four major literary sources in the Pentateuch, each with its own characteristic style and vocabulary. These were labeled: J, E, D and P. The J source used the name "Yahweh" ("Jahveh" in German) for God, called the mountain of God "Sinai," and the pre-Israelite inhabitants of Palestine "Canaanites," and was written in a vivid, concrete, colorful style. God is portrayed anthropomorphically, creating after the fashion of a potter, walking in the garden, wrestling with Jacob. J related how promises made to the patriarchs were fulfilled, how God miraculously intervened to save the righteous, or to deliver Israel, and acted in history to bring into being the nation.11 E used "Elohim" to designate God until the name "Yahweh" was revealed in Exod. 3:15, used "Horeb" as the name of the holy mountain, "Amorite" for the pre-Hebrew inhabitants of the land, and was written in language generally considered to be less colorful and vivid than J’s. E’s material begins in Gen. 15 with Abraham, and displays a marked tendency to avoid the strong anthropomorphic descriptions of deity found in J. Wellhausen considered J to be earlier than E because it appeared to contain the more primitive elements.

The Deuteronomic source, D, is confined largely to the book of Deuteronomy in the Pentateuch, contains very little narrative, and is made up, for the most part, of Moses’ farewell speeches to his people. A hortatory and emphatic effect is produced by the repetition of certain phrases: "be careful to do" (5:1, 6:3, 6:25, 8:1), "a mighty hand and an outstretched arm" (5:15, 7:19, 11:2), "that your days may be prolonged" (5:16, 6:2, 25:15). Graf had demonstrated that knowledge of both J and E were presupposed in D, and having accepted DeWette’s date of 621 B.C. for D, argued that J and E must be earlier. J was dated about 850 B.C. and E about 750 B.C.

The Priestly tradition, P, reveals interest and concern in whatever pertains to worship. Not only does P employ a distinctive Hebrew vocabulary but, influenced by a desire to categorize and systematize material, develops a precise, and at times a somewhat labored or pedantic, style. Love of detail, use of repetition, listing of tribes and genealogical tables, does not prevent the P material from presenting a vivid and dramatic account of Aaron’s action when an Israelite attempted to marry a Midianite woman (Num. 25:6-9) or from developing a rather euphonious and rhythmical statement of creation (Gen. 1). The Graf-Wellhausen hypothesis noted that P contained laws and attitudes not discernible in J, E, or D and reflected late development. P was dated around the time of Ezra, or about 450 B.C.

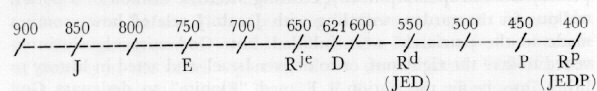

The combining of the various sources was believed to be the work of redactors. Rje, the editor who united J and E around 650 B.C. provided connecting links to harmonize the materials where essential. Rd added the Deuteronomic writings to the combined JE materials about 550 B.C., forming what might be termed a J-E-D document. P was added about 450-400 B.C. by Rp, completing the Torah. This hypothesis,12 by which the contradictions, doublets, style variations, and vocabulary differences in the Pentateuch were explained, can best be represented by a straight line.

Variations in the Graf-Wellhausen theory have been proposed since it was first expounded in the nineteenth century. Research into the composition of the individual documents produced subdivisions such as J1, J2, J3, etc. for J, and El, E2, and so on, for E until the documents were almost disintegrated by analysis.13 New major sources were recognized by other scholars. Professor Otto Eissfeldt discovered a fifth source beginning with Gen. 2 and continuing into Judges and Samuel which he labeled "L" for "Lay" source.14 R. H. Pfeiffer of Harvard University identified an "S" source in Genesis, so labeled because Pfeiffer believed it came from Seir (in Edom) or from the south.15 The great Jewish scholar, Julian Morgenstern, singled out what he believed to be the oldest document, "K," which, while in fragmentary form, preserved a tradition of Moses’ relationships with the Kenites.16 Martin Noth of Germany argued for a common basic source "G" (Grundlage for "ground-layer" or "foundation") upon which both J and E are developed.17

Along with developments stemming from the basic hypothesis, there have been challenges to certain aspects of the theory, including the dating of Deuteronomy18 and the pattern of development of the sources.19 Other scholars, particularly those representing conservative theological positions, have taken issue with the documentary hypothesis, arguing for the integrity of the Pentateuch and supporting Mosaic authorship.20 Most present-day scholarship accepts the basic premises of the documentary hypothesis – namely, that different source materials are to be found, that the labels J, E, D, P, are acceptable for major sources, and that the order of development is that proposed in the Graf-Wellhausen thesis.

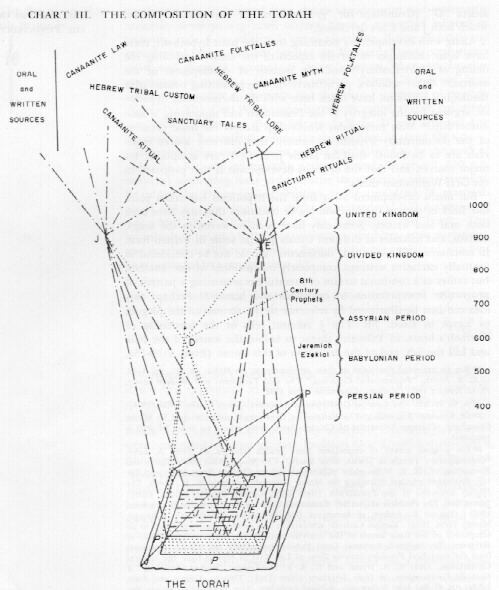

But much development away from the hypothesis has taken place too. Back of each of the four sources lie traditions that may have been both oral and written. Some may have been preserved in the songs, ballads, and folktales of different tribals groups, some in written form in sanctuaries. The so-called "documents" should not be considered as mutually exclusive writings, completely independent of one another, but rather as a continual stream of literature representing a pattern of progressive interpretation of traditions and history.21 Perhaps this idea can best be illustrated by reference to the account of the plagues in Egypt in Exod. 7 ff. The J account tells of the hardening of Pharaoh’s heart, of Yahweh’s threat to befoul the waters of the Nile and kill the fish, and of the execution of this threat (Exod. 7:14-15a, 16-17a, 18, 21a, 23-25). The E writer reinterpreted the story, adding to the account the rod of the wonder-worker and Moses’ threat to strike the water and turn the Nile to blood – a threat which he fulfills (Exod. 7:15, 17b, 20b). The Priestly author made other changes: Aaron, not Moses, is the wonder-worker, and it is Aaron who waves the rod not only over the Nile but other rivers, canals, ponds and pools, and all waters are turned to blood, including water stored in containers. The P writer explains that this terrible plague did not change Pharaoh’s mind, for Pharaoh’s priests can perform the same miracle. The important change made by the P editors is that Aaron, the symbol of the high priesthood in Israel, acts as the priest-magician-agent of God, performing the divine will. The interpretive pattern can be traced quite easily through the subsequent plagues by reference to the lists which delineate the contents of the various sources (see pp. 139 ff., 173 ff., 357 ff.).

The process of progressive interpretation did not exclude the incorporation of new materials, and some of the new material may have had a long history – oral or written – in circles outside of those which produced the earlier writings. For instance, in 1929 a Canaanite temple library, which can be dated from the fourteenth century B.C., was discovered at Ras es-Shamra, a site on the Syrian coast. The religious documents were found to contain words most familiar to us through Priestly writings of the Pentateuch, suggesting that part of the P material may be based upon sources as ancient as those used in J. Thus, we are confronted with a literary problem that is more difficult than the simple straight line analysis would suggest. Not only do we have materials coming from different periods of time and from different groups within society, and not only are these materials brought together and blended at different periods of history, but those who added the extra materials employed an interpretive principle in accordance with their theological convictions expanding, and, in a sense, expounding the writings with which they worked. Further, at some points the fusion of materials is so complete that it is impossible to distinguish sources – particularly where J and E are combined.

Because the documentary hypothesis is the most widely accepted of all theories of Pentateuchal analysis, this book will utilize, in principle, the conclusions reached by this method of research. One important change in the thesis accepted by many scholars will be observed: J and E, dated in Wellhausen’s time in the ninth and eighth centuries respectively, will both be placed in the tenth century, for reasons to be discussed later. Such a change does not deny that additions were made to each in the years before they were combined, but implies that the time of Solomon’s reign best fits the period for the accumulation of the core of J, and the early years of the divided kingdom are most appropriate for the writing of E.

It should be remembered that the documentary hypothesis, no matter what form it takes, is nothing more than an hypothesis – a proposition – assumed to explain certain facts (in this case doublets, contradictions, etc.). which provides the basis for further investigation. There is no way of proving that a J collection ever existed. Such a body of writings is assumed on the basis of evidence previously discussed.

Endnotes

- The term "Pentateuch" was used as early as the third century A.D. by Origen in reference to the first five books of the Bible – the Torah. The word is formed from the Greek terms pente-five, and teuchos-scroll. Scholars also use the words "Tetrateuch" to refer to the first four books, "Hexateuch" for the first six, "Septateuch" for the first seven books, and "Octateuch" for the first eight books.

- See II Chron. 25:4; Luke 2:22; 24:44.

- The Talmud is a vast collection of expositions on, or interpretations of, the Torah, representing the discussions of rabbis and schools from about the first five centuries A.D.

- Baba Bathra 14b-15a: "Joshua wrote . . . eight verses of the Law."

- The personal name of God is represented in Hebrew by the consonants YHWH, often called the "tetragrammaton" (four letters). On the basis of Greek transcriptions most scholars believe that the proper pronunciation of the word is "Yahweh" (often spelled in the German form "Jahveh"). This name became so sacred that it was not to be uttered, and the term "adonai" meaning "Lord" was read in its place. Most English translations use the form "LORD" for the Hebrew YHWH. The form "Jehovah" is an English hybridization composed of the consonants J-H-V-H and the vowels from "adonai" producing JaHoVaH. Cf. Theophile J. Meek, Hebrew Origins (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1950), pp. 82 ff.; R. Abba, "The Divine Name Yahweh," Journal of Biblical Literature, LXXX (1961), 320-328.

- "Elohim" is usually translated "God" in English versions. The general term for any deity is "el". The form "Elohim" is a plural, and the fact that it is used as a singular noun to refer to the God of Israel may reflect an awareness that the various manifestations of deity (el) are but extensions of a supreme "El," or "Elohim" embodying them all.

- This term, often translated "God Almighty," means "God of the Mountains." Cf. Wm. F. Albright, "The Names Shaddai and Abram," Journal of Biblical Literature, LIV (1935), 180 ff.

- Astruc, son of a Protestant minister who was converted to Catholicism, served as physician to King Augustus III of Poland and then to Louis XV of France, ultimately becoming regius professor of medicine at Paris. His work, Conjectures sur les memoires originaux dont il paroit que Moise s’est servi pour composer le livre de la Genese, was published in Brussels and Paris in 1753 and later appeared in German. He published several other theological essays, as well as a number of important medical treatises.

- H. F. Hahn, Old Testament in Modern Research (Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press, 1954, Fortress Press, 1966), p. 3.

- A. Weiser, The Old Testament: Its Formation and Development, trans. by D. M. Barton (New York: Association Press, 1961), p. 2.

- The characteristics of the individual sources will be discussed in greater detail later.

- For an excellent summary of the Graf-Wellhausen thesis, see J. Wellhausen, "Pentateuch and Joshua," Encyclopaedia Britannica, 9th ed. For greater detail see J. Wellhausen, Prolegomena to the History of Israel (New York: Meridian Books, 1957).

- See, for example, C. A. Simpson, The Early Traditions of Israel (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1948).

- Otto Eissfeldt, The Old Testament, an Introduction, trans. by P. R. Ackroyd (New York: Harper and Row, 1965).

- R. H. Pfeiffer, Introduction to the Old Testament (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1941).

- J. Morgenstern, "The Oldest Document in the Hexateuch," Hebrew Union College Annual, IV (1927), 1-138.

- For an extended discussion of these developments, see Hahn, op. cit., pp. 1-43, or C. R. North, "Pentateuchal Criticism," The Old Testament and Modern Study, H. H. Rowley (ed.) (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1952).

- A. C. Welch, The Code of Deuteronomy (London: James Clarke & Co., 1924).

- Cf. Yehezkel Kaufmann, The Religion of Israel, trans. and abridged by Moshe Greenberg (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960) where an order J-E-P-D is proposed.

- For a good survey of opposition from Jewish scholars, cf. Felix A. Levy, "Contemporary Trends in Jewish Bible Study," The Study of the Bible Today and Tomorrow, ed. H. R. Willoughby (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1947), pp. 98-115. Protestant scholars defending the Mosaic authorship include W. H. Green, The Higher Criticism of the Pentateuch (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1895) ; James Orr, The Problem of the Old Testament (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1906) ; Gleason L. Archer, A Survey of Old Testament Introduction (Chicago: Moody Press, 1964). Roman Catholic scholarship has moved from opposition to an acceptance of the basic tenets of the analytic method. Cf. Rome and the Study of Scripture (St. Meinrad, Indiana: Grail Publications, 1962) for official statements from the encyclical Providentissimus Deus of Leo XIII to reports from the Biblical Commission, 1961; R. A. Dyson and R. A. F. MacKenzie, "Higher Criticism," A Catholic Commentary on Holy Scripture (New York: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1953), pp. 61-66; Jean Steinmann, Biblical Criticism, The Twentieth Century Encyclopedia of Catholicism (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1958), pp. 81 ff. A good summary with bibliography by C. U. Wolf, "Recent Roman Catholic Bible Study and Tradition," appears in The Journal of Bible and Religion, XXIX (1961), 280-289.

- The phrases "progressive interpretation" and "continuing interpretation" will be used interchangeably to underscore the dynamic nature of the biblical material. Concepts and traditions did not remain static but were subject to reinterpretation and could be given new dimensions and new significance at a later date in the light of new experiences and insights. In the example involving Moses and Aaron given above, the roles of the two heroes undergo changes and Aaron assumes a more meaningful role commensurate with the growing importance of the high priesthood in the Jewish community.

Old Testament Life and Literature is copyright © 1968, 1997 by Gerald A. Larue. All rights reserved.

The electronic version is copyright © 1997 by Internet Infidels with the written permission of Gerald A. Larue.