Old Testament Life and Literature (1968)

Gerald A. Larue

Chapter 2 – How Do We Read?

THERE was a time when it was believed that the best way to read the Bible was to begin at Genesis and read straight through. Today we know that the Bible was not written in the sequence in which we find it, but developed slowly over hundreds of years. Consequently, passages written centuries apart may now appear side by side. To appreciate the development of Hebrew religious thought, and to understand concepts in terms of the time in which they were recorded, it is essential to read biblical passages in chronological order insofar as we are able to determine that order. During the past one hundred years or so, a methodology, which may be termed "historical-literary," has been developed. This approach seeks to do two things: to determine the specific time in history in which each part of the Bible was written, and to classify various literary genres (such as funeral laments or oracles of doom).

Basically, the historical-literary method recognizes that, because literature develops within definite historical contexts, specific problems, life situations and cultural patterns are often reflected. For example, a Psalmist wrote:

there we sat down and wept,

when we remembered Zion.

On the willows there

we hung up our lyres.

For there our captors

required of us songs,

And our tormentors, mirth, saying,

"Sing us one of the songs of Zion!"

Whoever wrote these words was captive in Babylon and in poetic form expressed unhappiness and nostalgia for Jerusalem (Zion). Reading the complete poem makes it apparent that the writer was one of the Hebrew people living in Babylon after the armies of King Nebuchadrezzar of Babylon had overrun the Near East and enslaved many peoples, and before Cyrus the Great, having defeated the Babylonians, permitted the people to return home (cf. 11 Chron. 36). The Psalm comes from the sixth century B.C.

Unfortunately, all biblical literature cannot be dated as easily as Ps. 137. Biblical scholars must employ, wherever possible, the techniques developed by historians to ascertain the period out of which a writing came, the specific life situation which prompted the writing, and the accuracy or reliability of any report of a past event.

THE PROBLEM OF HISTORY

Like other historians, the biblical scholar seeks to fix with certainty the factual nature of a reported event. He reaches conclusions by examining all relevant data from written sources, archaeological discoveries, sociological and anthropological research and, in some instances, geography. His conclusions must be true to all available facts and must be credible. For instance, 11 Kings 18:13 ff. reports the attack of the Assyrian King Sennacherib upon Jerusalem during the reign of King Hezekiah. How can we know that this event occurred? Fortunately, confirmation has come through the archaeologist’s discovery of the Taylor Prism, a hexagonal clay cylinder on which Sennacherib had inscribed an account of his military victories. At one point the siege of ,Jerusalem, including the name of King Hezekiah of Judah, is mentioned. Such coincidence of data provides what one scholar has labeled "controlled history."1 Having achieved a fixed "fact" in history, the historian next seeks to arrange other data around the event to establish a chronology on the basis of deductive reasoning.

Because the deductive process involves movement from the known to the unknown, from the factual to the probable, from fixed data to the schematic arrangement of related data, results are always tentative. Therefore, it is necessary to preface each section of this book with the acknowledgment, "Here is where we stand in the light of the evidence available at this particular moment. Tomorrow may bring new information that will necessitate a change in this conclusion."

In dealing with written records of the past, the biblical historian must evaluate the testimony he utilizes. Although it is clear that the Bible reports events with a high degree of accuracy, it cannot be assumed that all biblical history is accurate. For example, archaeological research has demonstrated that the city of Ai, reported in Josh. 8 to have been conquered by Joshua, was a heap of ruins centuries before Joshua’s time.2 Each event must be assessed individually. The scholar asks, "How did the writer of this account know of the events he reports? Was he an eye-witness? Did he talk to eye-witnesses, and if so, how long after the event? is he recording an old, written tradition or an oral source?" The further a report is from the event it describes, the greater the possibility of error or interpretation affecting its accuracy. Phrases such as "in those days" or "even to this day" reveal that the writer is conscious of reporting an event long after the time when it was supposed to have occurred.

How did the historian build his records in ancient times? Testimony was gathered from written and oral sources and, by exercising judgment as to the worthiness or appropriateness of the materials, the compiler blended them into a more or less homogeneous, connected narrative. In time, other writers might add to or reinterpret the account, regardless of the fact that the new material might contradict some details of the earlier accounts. The anointing of Saul is reported three times: once as a private ceremony (I Sam. 9:27-10:1) and twice as a public ritual (I Sam. 10:17-24, and 11:15). There are two accounts of the death of the Philistine giant, Goliath. In one, David is the conqueror, killing Goliath with a sling stone (I Sam. 17) ; in the other, Goliath dies at the hand of one of David’s warriors, Elhanan (11 Sam. 21:19). Still later, the writers of the books of Chronicles, who compiled their histories in the fifth century B.C., were troubled by the conflicting records and solved the dilemma by reporting that Elhanan killed Goliath’s brother, Lahmi (I Chron. 20:5).

Beyond the establishment of historical fact (the "happenedness" of an event) is the recognition of the point of view of the reporter. Like recorders of other national or religious documents, biblical writers not only selected events and details which best served their purposes, but also reported with national and religious bias. Battles and national events are reported to be under the control of the God of Israel, just as writers in other nations reported victories and conquests as ordained by their gods. For the Hebrew writer, Israel was the chosen people, peculiarly blessed, and written history echoed and reinforced this belief.

The biblical record, therefore, contains more than a listing of happenings and, like other historical writing, interprets data in the light of national and religious convictions. Events did not just happen. Battles were not won through superiority of armaments or numbers, but because the deity was personally involved. History had meaning the fulfillment of promises made to the patriarchs, the development of the holy nation, the blessing that were to come to the chosen nation as the people served and worshipped their God. The nation per se and the people as part of the nation were involved in a divine-human relationship, and it was essential for national welfare that this relationship be recognized and appreciated. To what extent cultic observances made use of this interpretation of history is not fully known, but there can be little doubt that a passage like Dent. 26:5-9 contains a recitation utilized at sanctuaries, reflecting awareness of the relationship of the nation’s history to the deity. "History" in the biblical sense reflects a national setting and relationship to a religious community, a "community of faith" as it has sometimes been called, and thus presents a particularistic interpretation. The events are there, together with the delineation of the meaning of the events for the nation.

HISTORY AND LEGEND

Around great figures in history, the heroes of a nation, legends invariably seem to rise. Shortly after Abraham Lincoln’s death, descriptions were published of private conversations between certain individuals and the president. Upon study by literary experts and historians, it was demonstrated that these accounts were legends, not history. Even during the lifetime of heroes legends may develop. In 1959 it was reported that, out of his great love and respect for British justice and law, Sir Winston Churchill provided £1,000 for the defense of a Nazi general on trial in Britain for war crimes. A letter from Sir Winston’s secretary quickly discredited this story. Churchill had not contributed any money to the defense of any war criminal, and, further, war criminals had not been tried in Britain. Investigating stories of Bible heroes is somewhat more difficult.

Semi-nomadic peoples, such as the Hebrews were prior to their invasion of Canaan, could not very well maintain written records. As David D. Luckenbill has observed, "History begins with the vanity of kings."3 Formal history begins when a monarch starts to record agreements reached with other nations, victories in battles (sometimes greatly exaggerated) , laws introduced or reforms instituted, on parchment, papyrus, clay or stone. Even with such documents the historian seeks confirming evidence of the recorded event. At this moment there is no external evidence of the events reported in the Bible prior to the Hebrew invasion of Palestine. The excavation of cities in Canaan has indicated that an invasion did take place. For example, at Tell Beit Mirsim (believed to be Debir) an abrupt cultural change was ascertained. Below the destruction layer Canaanite buildings and artifacts were found, and above, the pottery, buildings and defenses of the Hebrew conquerors. From that point onward, archaeological documentation of Hebrew habitation was available.4 Concerning the preinvasion or Mosaic period and the activities of the Patriarchs, evidence that at best can be labeled tangential has been recovered. The actual existence of the Patriarchs-Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and others-cannot be proven or disproven. The stories of their adventures must be treated largely as legend, containing here and there accurate memories of a tradition but preserving these memories in writings produced many years after the events they purport to describe-writings designed to dramatize the convictions held by the Hebrew people concerning God’s activity in human affairs.

The birth story of Moses (Exod. 2:1-10), probably recorded during the tenth century B.C., reflects the pattern found in the birth account of King Sargon of Agade who lived near the end of the third millennium B.C.The Sargon account reads:

Sargon, the mighty king of Agade, am I.

My mother was a changeling,5 my father I knew not.

The brothers of my father loved the hills.

My city is Azupiranu, which is situated on

the banks of the Euphrates.

My changeling mother conceived me, in secret

she bore me,

She set me in a basket of rushes, with bitumen

she sealed my lid.

She cast me into the river which rose not over me.

The river bore me up and carried me to Akki,

the drawer of water.

Akki, the drawer of water, lifted me out

as he dipped his ewer.

Akki, the drawer of water, took me as his

son and reared me.

Akki, the drawer of water, appointed me as

his gardener.

While I was a gardener, Ishtar6 granted me

her love,

And for four and . . . years I exercised kingship.7

The similarity of the Moses and Sargon accounts is obvious. Actually both stories reflect literary patterns often associated with heroes. The life of the hero is threatened when he is still a child; he escapes; he is unrecognized until he achieves his full status as a messiah or savior of the people. Very often his life pattern reflects the way in which a people consider their early history, for they look back upon their humble and troublous beginnings and marvel at what they have become. The life of the hero embodies the struggle of a nation or a group to achieve greatness.8 Having detected the hero motif in the Moses literature, one must consider the question of how much of the Moses cycle may be labeled "legend," and how much "history."9

Similar problems confront the scholar in the patriarchal narratives. Were Abraham, Isaac and Jacob real persons? Are their stories factual or legendary, embodying a fictionized history of the Hebrews, symbolizing the way the Hebrews looked back at their nomadic origins from the vantage point of their settled life in Canaan? Archaeological contributions provide no definite clues for determining whether or not these men ever existed. A Babylonian business contract from the beginning of the second millennium B.C. refers to a certain Abarama (Abraham), son of "Awel-Ishtar," but there is no possible way to link him with the Abraham of the Bible.10 Two Abrams, one associated with Egypt and the other with Cyprus, are mentioned in Ugaritic administrative texts. The references demonstrate that the name was known in the periods often associated with the patriarchs. The name of Jacob appears as the name of a Hyksos king (Ya’qob-er) about 1700 B.C.and, in an Egyptian list from the time of Pharaoh Thutmose III (ca. 1480 B.C.), a Palestinian town called Jacob-el (Ya’qob-el) is found, but these inscriptions do not help us very much.11

Moreover, the biblical texts confuse the problem. Genesis 10 lists Noah’s descendants and some of the "sons" can be identified as geographical areas. "Cush," mentioned in Genesis 10:6, is the area in North Africa south of the first cataract of the Nile known as Nubia. "Egypt" is called a son of Ham, and another son is called "Canaan," the area known today as Palestine. Among Canaan’s children is one called "Sidon" (Gen. 10:15), the name of a Phoenician seaport in northern Canaan. Abram (Abraham) is listed as one of the descendants of Shem, but among Sliem’s children we find areas listed as individuals -Elam, which is near Susa in Persia, and Asshur, which is Assyria. Among the immediate ancestors of Abram named in Gen.11 is Nahor, his grandfather, and Terah, his father. Nahor appears to be the city called Til-nakhiri, and Terah, Til-turakhi in Assyrian texts.12 The name "Haran" refers to a person in Gen. 11:27-30 but to a place in subsequent verses (Gen. 11:31-32; 12:4-5). When do people really become people and stop being symbolic representations of places? The pattern goes on and Esau becomes Edom and Jacob becomes Israel.

On the other hand, within the patriarchal narratives are accurate details relating to the age which they describe. Aspects of nomadic life could easily have been discovered by writers observing peoples who continued to dwell in the steppes and retained ancient desert customs. However, the Nuzi texts from the second millennium B.C. record practices similar to some reported in the patriarchal accounts. So far as we know at this moment, these specific practices were not observed by Canaanites or settled Hebrews and belong only to the early part of the second millennium. In the marriage agreements discussed in the Nuzi texts, a childless wife is obligated to provide a maiden for her husband so children should be born to him. Such a ruling explains why Sarah gave Hagar, her Egyptian maid, to Abraham (Gen. 16). The apprehension which Abraham expressed when he expelled Hagar and her child (Gen. 21:11) is, perhaps, explained by the Nuzi legal ruling that the handmaiden who bore a child for her master could not be driven out.13 Those who would place Abraham in the fourteenth or fifteenth century muster other evidence.14 Thus, although the Abraham stories may be labeled legendary to separate them from the historical, it should be remembered that a legend may be centered in real people and embody historical data. On the other hand, the record of a few accurate details does not guarantee the reliability of all reports. If biblical traditions actually go back to patriarchal times, then it must be assumed that a long period of oral transmission ensued before the accounts were recorded.15 Legends are important, not merely because they may contain accurate data, but because they provide us with an appreciation of the way in which people thought, and an understanding of what they believed at the time the legend was recorded. Legend belongs in the history ofhuman thought.

One characteristic that helps to distinguish legend from history is the tendency of those who record legend to use terms to indicate the great age of the account without being specific as to when, precisely, the event occurred. Gen. 19:36-38, which describes in most uncomplimentary terms the origin of the Moabite and Ammonite peoples, twice uses the phrase "to this day," indicating that the story is being recorded long after the event it appears to report. Gen. 22:14 concludes the story of Abraham’s near-encounter with child sacrifice with the phrase, "as it is said to this day," to indicate that the place name known in the writer’s time actually originated in "olden times."

Another distinguishing feature lies in the tendency of historical writings to deal with matters of public importance, events that affect the political and public welfare of the group. In legend, the account centers in and around a person who may embody or dramatize the spirit of the group for whom the tale is recounted.

In the discussion of the hero or central character the miraculous or the incredible is often incorporated to heighten the story. The principle of credibility must be applied to evaluate the possibility or the probability of the miraculous having occurred. At this point an understanding of the Weltanschauung, or world view, of the people of Old Testament time is important, for it was an accepted belief in the Near East that divine powers intruded in human affairs to alter and upset the ordinary pattern of existence. It seems only natural that literature of this period, whether it be Hebrew or Egyptian, Babylonian or Assyrian, should reflect such a belief. Thus, when we read of an iron axehead floating to the surface of a pond (II Kings 6:3-6), or of a magic jar of oil which continued toproduce oil until all available containers were full (11 Kings 4:1-6), the principle of credibility compels us to label these accounts legendary, not forgetting that to the non-scientific mind of earlier times such events were explicable on the grounds of belief in supernaturalism. To question the supernatural as it appears in the Bible is disturbing to some, but what would be labeled legend in Greek or Roman or other non-biblical writings deserves the same label when found in the Bible.

Different types of legends can be recognized in the Bible.16 The aetiological legend explains why something is the way it is. For example, Gen. 11, the story of the tower of Babel, explains why men who are related through a common father, Noah, speak different languages. The explanations must be approached in the light of the time when they were recorded. In one sense, because aetiological legends attempt to answer the question "why" about the environment, they might be said to mark the beginnings of science, without a scientific methodology. The ethnological legend is concerned with relationships existing between certain groups at a certain point in history and attempts to explain that relationship in terms of past events. For instance, Canaan, one of the sons of Noah, is condemned by a curse to slavery in Gen. 9:25 because his father, Ham, looked upon Noah’s nakedness. Actually, the account was written after the Hebrews had established their kingdom and exerted their authority over Canaan. The legend explains, in terms of a curse, why the slave-master relationship developed. Etymological legends explain why certain places bear the names they do (see Gen. 19:22; 21:31). Ceremonial legends explain why certain rituals are performed in the Hebrew cultus (cf., Exod. 12:26 ff.; Exod. 13:14 ff.). Geological legends are concerned with the explanation of certain natural phenomena. The pillar of salt, a landmark probably well known in Old Testament times17 is explained by the legend of Lot’s wife (Gen. 19:24-26). The literary categories devised by modern scholars enable the reader to appreciate the creative genius of the Hebrew writers, even though such classifications may seem to pour this genius into fixed molds. But the Hebrews were not bound by patterns and, on occasion, differing types of legends are combined (cf., Gen. 32:30, a combination of etymological and ceremonial legends).

The necessary separation of legend and history does not imply that legend is to be thought of as deceit or falsehood. It is not the function of legend to deceive, but to portray dramatically real beliefs and convictions held by people concerning origins and to answer the question "why" concerning certain characteristics of the time. How legends were used by the Hebrew people is not known for certain, but it is possible that some were recited at sanctuaries associated with the individual hero at cultic festivals.18

MYTH, FABLE AND OTHER LITERARY CATEGORIES

Myth, which is classically but somewhat narrowly defined as "stories of the gods," is distinguished from legend by the divinity of the central figure or figures. As there is no true polytheism in the Old Testament (only echoes, cf., Dent. 32:8-9; Ps. 82:1), only the creation accounts (Gen. 1-3), the story of the sons of God (Gen. 6), and perhaps Job 1-3, are placed in this category. The flood accounts and the story of the tower of Babel are combinations of myth and legend.

More broadly defined, myth is the description of any action of the deity in human affairs. Such a definition tends to embrace almost every Old Testament statement about the activity of God and, thus merging with what is generally classified as "theology,"19 would nullify any attempt to analyze Old Testament literature.

A third definition seeks to interpret myth in terms of ancient Near Eastern thought patterns and lay stress upon aetiological factors. Like other peoples of the Near East, the Hebrews conceived of the world as a flat disc beneath the solid vault of heaven which met the earth or sea at the horizon. Such a concept, we know, was based upon optical illusion, but peoples of early times had developed neither instruments nor techniques for scientific investigation of their environment. To explain the beginnings of life or why things are as they are, the Hebrews, like others, developed explanations which modern scientific and historical knowledge render unacceptable, but which reveal to us how people thought and what they believed. Only as we are cognizant of the ancient belief in a three-story world (heaven above, earth, and Sheol, the place of the dead, below) and are sensitive to the tendency to interpret experience and "reality" in mytho-poeic terms can we begin to understand how the Hebrew writers responded to their world.

It would seem preferable to recognize in myth a literary vehicle developing out of the creative and sensitive spirit of man, as man, in awareness of the totality of his experiences, including change, decay, death, birth, the cycles of nature, and strange, unexpected happenings, Bought to make sense of, or give order to, or give significance to his experience. This deep awareness of his environment and of his experience led to the presupposing of creative powers which, in primeval time, "in the beginning," brought order into being by overcoming chaos.20 What happened "then" had relevance for "now." As chaos was defeated "then," so it must be overcome "now." Once the normal time span, whether it be the cycle of the year or some other period, had run its course, it had to be renewed; life had to be re-energized and recharged; re-creation had to ensue, symbolically, through the defeat of chaos.21

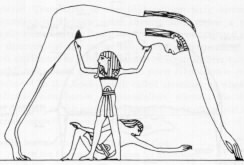

EGYPTIAN COSMOLOGY. Egyptian cosmology pictured Nut, the sky goddess, arched to form the heavens; Geb, the earth god, reclining so that the curvature of his body symbolized valleys and hills; and Shu, the air god, separating heaven and earth and supporting the heavens. The arch of the sky is also represented by the figure of Nut as the heavenly cow with Shu in the same posture beneath the animal figure. (Based on the fifteenth century B.C. papyrus of Ani, the so-called "Book of the Dead.")

EGYPTIAN COSMOLOGY. Egyptian cosmology pictured Nut, the sky goddess, arched to form the heavens; Geb, the earth god, reclining so that the curvature of his body symbolized valleys and hills; and Shu, the air god, separating heaven and earth and supporting the heavens. The arch of the sky is also represented by the figure of Nut as the heavenly cow with Shu in the same posture beneath the animal figure. (Based on the fifteenth century B.C. papyrus of Ani, the so-called "Book of the Dead.")

The myth, which conveys beliefs about what happened at the beginning, had environmental significance. Events of the first creation were re-enacted through ritual and ceremonial cult drama, and in this re-enactment the worshiper was a participant. He was, so to speak, there, involved in the renewal of life. Myth is a literary expression relating the ideal to the real, binding that which took place in the, ancient past to the ritual act of the present. As such, it becomes for the believer the foundation of reality, for he is linked physically, emotionally, intellectually, spiritually and socially with fundamental beginnings, with his own primeval origins. Such a definition emphasizes that, for people in Old Testament times, myth was a living reality. It was more than a story told about ancient times; it was a reality experienced as words, articulated, took form and meaning in cul dramatization.22

All biblical mythology does not fit into the seasonal or cultic drama pattern.23 Where remnants are found of ancient myths reflecting the battle between chaos and order, or between God and the primeval monster of the deep (cf. Isa. 27:1, 30:7, 51:9-10; Ezek. 29:3-5, 32:2-6), the myth has been "historicised" and God’s enemy, whether it be Egypt or Babylon, is described as the monster of chaos, or the myth is related to a past event, such as the Exodus from Egypt (Ps. 74:13 ff.).24 Other categories of biblical literature are: fable, in which animals and plants are the dramatis personae and a moral is drawn or a lesson taught (cf. Judg. 9:7-15) ; fiction, which may also teach a lesson (Jonah, Ruth) ; and apocalyptic literature, which deals with the end of the age (Daniel) . Each category of literature has its own purpose and conveys in its own way the writer’s intent. it must be assumed that different forms of literary expression were not employed accidentally. To understand what each writer is attempting to say, it is important to recognize the literary form utilized, for problems develop when myth is treated as history or when fiction is accepted as fact.

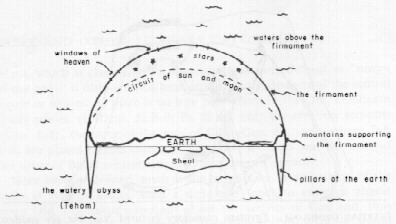

HEBREW COSMOLOGY. Because no depictions of the Hebrew concept of the universe have been found, any reconstruction is conjectural and is dependent upon the interpretation of information found scattered through the Bible. The flat earth is a disc, the heavens, like an inverted bowl, are solid, holding back the waters above the firmament, and only as the windows of heaven were opened could these external waters fall upon the earth. Above the firmament and the external waters was the court of heaven. Outside the heaven-earth complex was the water abyss (Heb.: Tehom).

HEBREW COSMOLOGY. Because no depictions of the Hebrew concept of the universe have been found, any reconstruction is conjectural and is dependent upon the interpretation of information found scattered through the Bible. The flat earth is a disc, the heavens, like an inverted bowl, are solid, holding back the waters above the firmament, and only as the windows of heaven were opened could these external waters fall upon the earth. Above the firmament and the external waters was the court of heaven. Outside the heaven-earth complex was the water abyss (Heb.: Tehom).

POETRY

Writers of the Old Testament were not limited to expression in prose; poetry was extensively employed. In modern translations, large portions of what used to be printed as prose are now in poetic form. It is estimated that, whereas only 15 per cent of the Old Testament appeared as poetry in the King James version of 1611, in the Revised Standard Version of the Bible about 40 per cent of the text is printed as poetry.25 Translators of the 1611 edition were limited in their understanding of Hebrew word rhythm and, unless a writing was specifically identified as a "song" or "psalm," it was printed as prose.

The discovery of the major key to the understanding of Hebrew poetry is attributed to a British scholar, Bishop Robert Lowth, who in 1753 published a work titled De sacra poesi Hebraeorum praelectiones academicae.26 In this book Lowth called attention to what he labeled parallelismus membrorum, or parallelism, wherein the thought patterns of one part of the verse are expressed in another part of the verse in different terms.27 For example:

The heavens are telling the glory of God;

and the firmament proclaims his handiwork.

The thought of the first line is repeated in the second: the word "heavens" is paralleled by the word "firmament," the verb "are telling" means the same as "proclaim," and the Psalmist believed that "the glory of God" was manifested in "his handiwork." This precise echoing of the concept of one line in the following line is called "synonymous parallelism." Where the second line expresses the antithesis of the first line, thus emphasizing the thought, the form is called "antithetical parallelism,"28 as in:

A soft answer turns away wrath,

but a harsh word stirs up anger.

The principle which lies behind the Hebrew verse has been succinctly stated by T. H. Robinson: "Every verse much consist of at least two ‘members,’ the second of which must, more or less completely, satisfy the expectation raised by the first."29 Rhyme as we know it in English poetry is not a dominant characteristic of Hebrew poetry (see Gen. 4:23, the "Song of Lamech" in which each line ends in an "i" sound). Sense rhythm or parallelism was not the creation of Hebrew poets, for the same characteristics are found in Egyptian, Babylonian and Canaanite poetry predating Hebrew poems.30

Like the poetry of other peoples, Hebrew poems made use of hyperbole to express emotions in superlative terms ("my bones burn like a furnace" – Ps. 102:3) and employed highly figurative language and similes to convey impressions (The righteous man is "like a tree" – Ps. 1) . Poetry is used for love songs (Song of Songs), taunt songs to mock the enemy (Judg. 5:28-30), praise songs (Ps. 145), wisdom sayings (Proverbs) , prophetic oracles, and many other types of expression.

PROBLEMS OF TEXT AND AUTHORSHIP

In attempting to understand a particular writing, whether it be prose or poetry, the biblical scholar seeks to discover, wherever possible, who wrote the material, when, where, why, to whom or for whom, and under what circumstances. This methodology received the title of "higher criticism" to distinguish it from "lower criticism" which is concerned with manuscript or textual study.

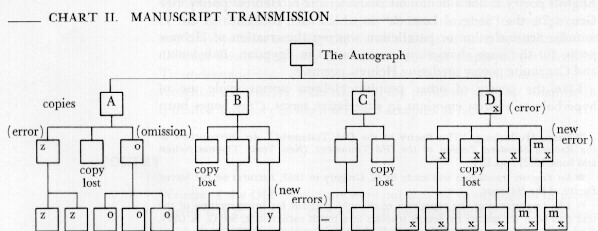

In lower criticism, the history of a particular writing is depicted as a stream, the source of which is the "autograph" or the original copy as it left the author’s hand. (See Chart II.) As autographs are no longer available we must depend upon the accuracy of those who through the centuries have copied and recopied the words. Until the discovery of scrolls in caves near the Dead Sea in 1947, the earliest Hebrew manuscripts of the Bible known to translators were from the ninth century A.D. Textual experts, comparing manuscripts, find variances. Copyists, being human, made many simple errors in the process of transmission. An early copyist’s error might affect hundreds of subsequent manuscripts. For example, if a weary scribe let his eyes drop from one line to another ending in the same word thereby omitting several intervening lines (haplography), and his uncorrected manuscript was copied and recopied, a textual critic would have to decide whether the intervening lines appearing in some manuscripts were added by a later writer, or had been inadvertently omitted by an early copyist. Sometimes a line or word is copied twice (dittography) , and on occasion a scribe will do what many modern typists often do, invert a word (metathe sis). The lower critic compares manuscripts, recognizes "families" by the relationship of spelling patterns and errors, learns to distinguish between careful and careless copyists, and uses every skill and tool he possesses to provide the most accurate manuscript.

Chart II – The greater the distance between an individual manuscript and the autograph the greater the possibility of the manuscript containing copyists’ errors. Once an error had been made, those who copied tended to reproduce it. A scholar with an impressive number of manuscripts representing the "D" family in the above chart and with few manuscripts from A, B and C must evaluate the material to determine whether the D evidence should be allowed to outweigh the other evidence. Meanwhile he may be confronted with dozens of individual textual problems in the A, B and C families.

The higher critic focuses attention upon the author. He seeks to discover all that he can concerning the time of the writing, the cultural setting, the situation which prompted the writing and the nature of the group for whom the writing was intended. Sometimes the author’s identity is easily ascertained, for an editor may have prefaced the work with a statement of identification. However, a name placed at the beginning of a book may not signify the author. The name Joshua stands over one book of the Bible which is certainly not by Joshua, for Joshua’s obituary appears in the last chapter. The book is about Joshua. The same thing may be said about the first five books of the Bible which are called the "Books of Moses." Moses’ death is recorded in the last chapter of Deuteronomy, so he cannot be the author of these verses, and, as we shall see presently, other matters make it quite clear that while Moses is the central character, he is not the author of these books.

Even when a book does appear to be the work of the individual named in the title, additional material may have been added. The book of Isaiah refers to King Uzziah (ch. 6) and King Ahaz (ch. 7), both of whom lived in the eighth century B.C. when Isaiah prophesied. Chapter 45 contains a reference to King Cyrus of Persia, who, in the sixth century B.C., released the Hebrew people from their captivity in Babylon. Because of differences in style, in details reflecting a different historical setting, and in messages directed to people in a different life situation, Chapters 40 onward are believed to be the product of someone living in Babylon two centuries after the time of Isaiah of Jerusalem. The book of Isaiah is, therefore, a composite work. It is the task of the higher critic to attempt to discover, wherever possible, the work of the original writer and to study that writing in terms of the historical period out of which it came. He must apply the same methods and questions to the later additions.

Endnotes

- Cyrus H. Gordon, Introduction to Old Testament Times (New Jersey: Ventnor Publishers, 1953), pp. II f.

- None of the several hypotheses set forth to explain this apparent error is completely satisfactory, for either the motives of the biblical writer are questioned or he is accused of a high degree of confusion. One theory labels the account a fabrication designed to explain the heap of ruins at Ai; another suggests that the men of Bethel (a city about a mile and a half away) made a stand at Ai before falling back to Bethel; and a third suggests that the account of the fall of Bethel was transferred to Ai. Cf. John Gray, Archaeology and the Old Testament World (New York: Harper and Row, 1962), P. 93; G. E. Wright, Biblical Archaeology (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1962), p. 81.

- David D. Luckenbill, The Annals of Sennacherib (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1924), p. 1.

- Cf. C. C. McCown, The Ladder of Progress in Palestine (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1943), pp. 91 f.; Wm. F. Albright, From Stone Age to Christianity (New York: Doubleday-Anchor, 1957), pp. 284 f.

- The term "changeling" conveys no meaning. It is possible the term meant "vestal" or one associated in some way with temple personnel.

- Ishtar was the goddess of vegetation, fertility, and love.

- Trans. by E. A. Speiser, in James B. Pritchard (ed.) , Ancient Near Eastern Texts (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1950), p. 119. Used by permission.

- Cf. Lord Raglan, The Hero (New York: Vintage Books, 1956) ; Otto Rank, The Myth of the Birth of the Hero (New York: Vintage Books, 1959); Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces (New York: Meridian Books, 1956).

- The Moses story reflects accurate details concerning adoption procedures as known from Mesopotamian documents, cf. B. S. Childs, "The Birth of Moses," Journal of Biblical Literature, LXXIV (1965), 109-122.

- George A. Barton, Archaeology and the Bible (Philadelphia: American Sunday School Union, 1916) , pp. 352 ff.

- Cf. John Bright, op. cit., p. 70.

- Ibid.

- Cf. James B. Pritchard (ed.) , Ancient Near Eastern Texts (henceforth ANET) (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1950) , P. 220.

- Cyrus H. Gordon, "Hebrew Origins in the Light of Recent Discoveries," A. Altmann (ed.) , Biblical and Other Studies (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1963). See also Cyrus Gordon, "The Patriarchal Age," Journal of Bible and Religion, XXI (1953), 238-243; and Introduction to Old Testament Times, pp. 1-119.

- Raglan, op. cit., pp. 13 ff., limits folk-memory to a period of 150 years. On the other hand, Eduard Nielsen, Oral Tradition (London: S.C.M. Press, 1954), believes that the written records of the Old Testament prior to the sixth century B.C. (the Exile) were negligible and that the writing, which must be dated in the post-Exilic era, is dependent upon oral tradition.

- Hermann Gunkel, The Legends of Genesis (Chicago: The Open Court Publishing Co., 1901), pp. 24 ff. (republished in 1964 by Schocken Books, New York).

- Some modern scholars identify the pillar with the stone outcropping on the mountain ridge to the southwest of the Dead Sea known as the Jebel Usdum. Cf. Curt Kuhl, The Old Testament, Its Origins and Composition, trans. by C. T. M. Herriot (Richmond: John Knox Press, 1961), P. 43.

- "Legend" in The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible (New York: Abingdon Press, 1962).

- G. von Rad, Old Testament Theology, trans. by D. M. G. Stalker (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1962) , I, 105 f.; E. Jacob, Theology of the Old Testament, trans. by A. W. Heathcote and P. J. Allcock (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1958) , pp. 11 f.

- The struggle between benevolent and malevolent forces could be witnessed in the battle between sterility and fertility in the land, light and darkness in the heavens, life and death in nature.

- The cyclic pattern was apparent in lunar changes, seasonal periods, rhythms of birth and death, etc.

- Cf. T. H. Gaster, Thespis, Ritual, Myth and Drama in the Ancient Near East (New York: Henry Schuman, I950), pp. 3-72; H. and H. A. Frankfort, "Myth and Reality," Before Philosophy (Baltimore: Penguin Books, I959) ; B. S. Childs, Myth and Reality in the Old Testament (London: S.C.M. Press) , pp. 13-27; C. Kerenyi, "Prologomena," in C. G. Jung and C. Kerenyi, Essays on a Science of Mythology, trans. by R. F. C. Hull (New York: Harper and Row, 1963).

- G. H. Davies, "An Approach to the Problem of Old Testament Mythology," Palestine Exploration Quarterly (London: Office of the Fund, 1956), pp. 89 f.

- Cf. Artur Weiser, The Old Testament: Its Formation and Development, trans. by D. M. Barton (New York: Association Press, 1961) , pp. 57 f.

- James Muilenburg, "The Poetry of the Old Testament," An Introduction to the Revised Standard Version of the Old Testament (New York: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1952) , pp. 62 f.

- An English translation was made by G. Gregory in 1847, Lectures on the Sacred Poetry of the Hebrews.

- The importance of the repetition of thought patterns for interpretation of the text had been recognized by Jewish scholars at a much earlier date. See G. B. Gray, The Forms of Hebrew Poetry (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1915).

- Other types include "stairlike parallelism," "emblematic parallelism introverted parallelism." Cf. C. A. and E. G. Briggs, A Critical and Exegetical Commen tary on the Psalms (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1912) , I, Introduction.

- Theodore H. Robinson, The Poetry of the Old Testament (London: Gerald Duckworth & Co., Ltd., 1947), P. 21.

- Cf. ANET, pp. 406 ff. (Egyptian), pp. 434 ff. (Babylonian), pp. 129 ff. (Canaanite).

Old Testament Life and Literature is copyright © 1968, 1997 by Gerald A. Larue. All rights reserved.

The electronic version is copyright © 1997 by Internet Infidels with the written permission of Gerald A. Larue.