Old Testament Life and Literature (1968)

Gerald A. Larue

Chapter 14 – The History of the Kingdoms

THE record of Solomon’s greatness fails to indicate the seething bitterness and resentment that must have been developing among the people. Only when Rehoboam appeared for succession rites were the feelings expressed by those who bore with smoldering anger the heavy burdens of Solomon’s despotism. The northern and southern peoples were kept from full union by geographical factors, by the northern people’s basic distrust of the Davidic monarchy with its center in Jerusalem (a southern city despite its proximity to the north-south border), by resentment to Solomon’s extravagant excesses and the resultant heavy taxation, and possibly even by different religious or theological outlooks indicated by the support of the schism by the prophet Ahijah (I Kings 11:29 and following verses). Judah appears to have accepted Rehoboam without question, but when the young prince went to Shechem to be anointed king and received the approbation of the people, he was confronted with a demand for a policy statement. The request reveals the severity of Solomon’s rule:

Your father made our yoke heavy. Now therefore lighten the hard service of your father and his heavy yoke and we will serve you. (12:4)

Rehoboam turned to his advisors for counsel: the elder statesmen recommended compliance while the younger men advocated a "get-tough" policy. Rehoboam accepted the latter. His arrogant and harsh rejection provoked immediate response: withdrawal from the United Kingdom. The rebel cry was an old one (cf. II Sam. 20:1):

What portion have we in David? We have no inheritance in the son of Jesse. To your tents, 0 Israel! Look now to your own house David. (12:16)

Jeroboam, the exiled taskmaster who had recently returned from Egypt, became the first king of Israel. Rehoboam ruled Judah. Gone forever was the United Kingdom; and in the eighth century Israel disappeared altogether from history.

INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENTS

As the southern kingdom reaffirmed its loyalty to the Davidic line by retaining Solomon’s rash offspring as monarch and the northern kingdom asserted independence, two great powers destined for significant roles in Palestinian affairs were preparing for expansion of empire. Egypt, which had been quiescent during the period of the United Kingdom, was conquered by a Libyan prince named Sheshonk-or Shishak as the Bible prefers to call him-and the twenty-second Egyptian dynasty was established. Five years after Solomon’s death, Sheshonk’s armies invaded Palestine. I Kings 14:25 records only the plundering of the Temple treasury, but II Chronicles 12:4 suggests wider desolation, a detail substantiated by Sheshonk’s account found at Karnak which records the sacking of towns in southern Galilee, and by a fragment of what may have been an Egyptian victory stele bearing Sheshonk’s name discovered at Megiddo. Fortunately for the Hebrew kingdoms, Sheshonk appears to have been satisfied with the booty from the single raid, for he made no effort to control Palestine. Toward the close of the eighth century, Egypt was conquered by an Ethiopian monarch, Pi-ankh, and in the seventh century, when the Assyrians embarked upon world conquest, Egypt was invaded, first by Esarhaddon in 671, and again by Ashurbanipal in 667.

At first, the gradual growth of Assyria did not directly affect Palestine. Tiglath Pileser I (1114-1076) pushed Assyrian control to the Mediterranean but not southward into Hebrew territory. In the ninth century, Ashurnasirpal II (883-859) developed the Assyrian war machine to a peak of strength and from this time onward Assyrian politics influenced Palestine. In 853, according to an inscription of Shalmaneser III (858-824), Ahab of Israel suffered defeat and paid tribute after he had joined a coalition of twelve Syrian kings to contest Assyrian expansion at Qarqar. Shalmaneser, after neglecting Syria for a few years, began a systematic plundering of the area. That Israel paid tribute is clear from the black obelisk of Shalmaneser III on which Jehu is portrayed prostrate before Shalmanesar, and a list of the booty paid to Assyria is given. One eighth century inscription records tribute taken from Menahem of Samaria by Tiglath Pileser III (747-727) (cf. II Kings 15:19), while another refers to payments made by "Azriau of luda," possibly Azariah or Uzziah of Judah, suggesting that both Hebrew kingdoms contributed to the growing wealth of Assyria. In 722, the son of Tiglath Pileser III, Shalmaneser V (726-722), attacked Israel but died before the final victory which was accomplished by his successor, Sargon II (721-705). According to his report, Sargon led away 27,290 inhabitants from Samaria to be enlisted in his army. Conquered peoples from other areas were moved into Israel so that revolt of the thoroughly mixed population became unlikely. The kingdom of Israel had come to an end and the northern Hebrew nation was part of the Assyrian kingdom. By payment of heavy taxes, Judah avoided the fate of Israel, but Assyrian influence in Judaean affairs was strong.

During the period of the two Hebrew kingdoms, in addition to pressure from Egypt and Assyria, Israel had other border problems. When the northern kingdom separated from the south, the Philistines attempted to regain lost territories, the Aramaeans of Damascus created trouble on the northern frontier, and the powerful city-state of Tyre, with whom Israel ultimately formed an alliance through marriage, proved to be a persistent menace. Judah, always open to Egypt on the southern boundary and now weakened by the loss of Israel, was threatened by Edom, Moab and Philistia.

KING ASHURNASIRPAL II OF ASSYRIA and an attendant in a winged costume participate in a religious ritual. The low relief, carved in gypseous alabaster, is from the ancient Assyrian city of Calah (Nimrud) excavated by Austin Henry Layard from 1845 to 1848 and by M. E. L. Mallowan from 1949 to 1961. Ashurnasirpal’s inscriptions boast of the ruthless treatment of captive peoples and of the terror inspired by Assyrian military tactics.

KING ASHURNASIRPAL II OF ASSYRIA and an attendant in a winged costume participate in a religious ritual. The low relief, carved in gypseous alabaster, is from the ancient Assyrian city of Calah (Nimrud) excavated by Austin Henry Layard from 1845 to 1848 and by M. E. L. Mallowan from 1949 to 1961. Ashurnasirpal’s inscriptions boast of the ruthless treatment of captive peoples and of the terror inspired by Assyrian military tactics.

Against this background of Near Eastern history the internal history of the Hebrew kingdoms must be studied. For this history we are dependent upon accounts in Kings and Chronicles and limited information coming from archaeological research. The Deuteronomic editors of Kings may have drawn upon official court records, but their work betrays theological and Judaean bias. Each monarch is judged on the basis of his adherence to the principles of southern Yahwism and his opposition to Ba’alism and other religions. Consequently no Israelite king is commended and only two Judaeans, Hezekiah and Josiah, are fully approved, although six others receive modified approbation. When the editorial evaluation is removed, there remains an outline of successive rulers with brief comments on significant events of their reigns.

Writing in the fourth century, the Chroniclers utilized an edition of Kings similar to the one we possess but did not hesitate to supplement the narratives. Some additions appear to have historical validity; others reflect theological convictions. Historical data in Kings and Chronicles must be accepted cautiously, and most additional material in Chronicles remains sub judice, except where sustained by archaeological or other confirming evidence.

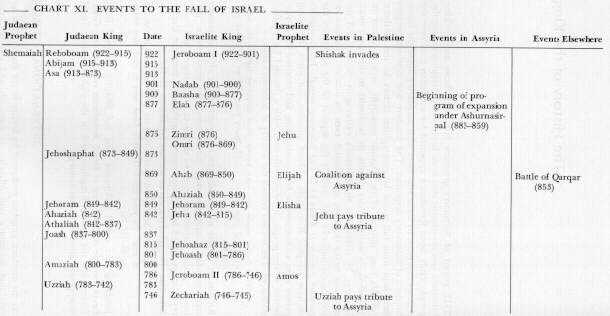

The outline below presents, in parallel columns, the history of Judah and Israel up to the time of the collapse of Israel (722/721). The dates are approximations and, because biblical chronology is not fixed, variations of two to five years may be assumed in some instances. Asterisks indicate a change of dynasty.

| Judah | Israel |

(Read I Kings 12-14) Rehoboam (922*) , son of Solomon, having lost Israel, Ammon and Moab, was determined to regain these territories. Dissuaded by Shemaiah’s prophetic warnings, he strengthened Judaean fortifications, but his efforts failed to prevent invasion by Sheshonk of Egypt. Judaean villages were destroyed, Jerusalem entered, and the Temple plundered. The raid must have affected Judaean military strength adversely, and the intermittent warfare with Israel attempting to fix the Israel-Judah border continued to drain the national resources. (Read I Kings 15) Abijah (915) or Abijam, Rehoboam’s son and successor, may have pushed Judaean borders as far north as Bethel (II Chron. 13), but he was unable to retain control of this important Israelite city. (913) Asa, the next king, is commended by the editors for his efforts to subdue the fertility cults. During his reign, border warfare with Israel continued. When Baasha began to build Ramah to sever Judah’s northern trade route, Asa bribed Ben Hadad of Syria to move the Syrian armies to Israel’s northern frontier. Baasha’s men withdrew from Ramah and Asa stole the building materials and constructed fortresses at Mizpah (possibly Tell en-Nasbeh) and Gibeah just north of Jerusalem. The Chroniclers record a battle between Judah and the Cushites or Ethiopians (II Chron. 14:9 ff.) but this has not been verified.

It was not until Jehoshaphat (873), Asa’s son, became king that peace was established between the two Hebrew kingdoms and cooperative attacks on mutual enemies were undertaken. Jehoshaphat’s son, Jehoram, married Athaliah, daughter of Ahab of Israel (II Kings 8:26), thus linking the Divided Kingdom through royal marriage. The Judaeans joined the Israelites in the Syrian-Israelite war (I Kings 22:2f.) and later, when the Moabites rebelled, southern soldiers assisted Israel (II Kings 3:7 ff.)

(Read II Kings 3, 8) Jehoshaphat was succeeded by his son Jehoram (849), son-in-law of Ahab, and during his reign Edom broke free of Judaean control (II Kings 8:20-22).

When Jehoram’s son Ahaziah (842) (Read II Kings 9-10), king of Judah, was killed by Jehu of Israel, his mother Athaliah (842*) (Read II Kings 11) ascended the throne to become the first and only Hebrew woman to reign. Eligible heirs, with the exception of Joash or Jehoash, the infant son of Ahaziah, were murdered. Joash was concealed in the temple by his aunt, the wife of the chief priest (II Chron. 22:11). Athaliah was not tolerated for long. She was an usurper, standing outside of the Davidic line, and she encouraged Baalism. Joash (837*) (Read II Kings 12-13) was seven years old when he was crowned king in a secret ceremony and, in the uprising that followed, Athaliah was murdered. As Jehu persecuted Baal worshippers in Israel, Joash attacked them in Judah. Joash was murdered by his servants and his son, Amaziah (800) (Read II Kings 14), ascended the throne. Territory lost to Edom was repossessed and the Edomite mountain fortress of Sela (Petra) invaded. In war with Israel Amaziah was defeated and Jehoash’s army looted the holy temple. Like his father before him, Amaziah died at the hands of his servants. Azariah or Uzziah (783), son of Amaziah, fought the Edomites when he came to the throne and Judah gained control of the important Red Sea port of Elath (Ezion-geber). Unfortunately, Azariah contracted leprosy (attributed by the Chroniclers to a cultic violation) and was compelled to live in isolation, and his son Jotham governed as regent (cf. II Kings 15:1-7; II Chron. 26). In the year that Azariah died the prophet Isaiah began his work.

Jotham (742) was regent for eight years before gaining the crown. Little is known of his reign except that the Temple was repaired (II Kings 15:33ff.) and, according to the Chronicler, war was waged with Ammon (II Chron. 27:5ff.). Ahaz (735), son of Jotham, refused to join an anti-Assyria coalition and, in the so-called Syro-Ephraimitic war, Judah was attacked by King Rezin of Syria and King Pekah of Israel. About the same time Edomites and Philistines united against Judah (II Chron. 28:1-21). The pressure was too much and Ahaz called on Tiglath Pileser for help. Judah paid huge indemnities for this aid and Assyrian deities were introduced into the temple of Yahweh. During this period, Edom recaptured the seaport of Elath. Ahaz’ international policies were vigorously opposed by the prophet Isaiah, but there can be little doubt that Ahaz’ refusal to participate in the anti-Assyria pact and his voluntary surrender of sovereignty saved Judah from Israel’s fate (II Kings 16:7ff.). Judah became a vassal to Assyria, the mightiest empire the Near Eastern world had known. |

Jeroboam (922*) had won a kingdom without headquarters or government. His immediate task was the development of administrative patterns. Shechem became the capital and was fortified. To offset the attraction of the Jerusalem temple, royal sanctuaries were dedicated in the border cities of Dan and Bethel. Within these shrines golden calves, symbols of Yahweh, or perhaps pedestals upon which the invisible deity stood, were placed, and festal observances paralleling those of Jerusalem were instituted. Chapters 13-14 of I Kings which condemn Jeroboam are largely homiletic. Chapter 13, a legend about an unknown prophet, comes from the post-Josiah period (cf. 13:2). The story of the illness of Jeroboam’s son may have an historical core (I Kings 14:16, 12, 17) that was expanded by later writers. What result the Sheshonk invasion had is not known, but the economy must have suffered. (901) Nadab, Jeroboam’s son who reigned less than two years, was murdered with all members of Jeroboam’s family by Baasha (900*) of the house of Issachar. Baasha fought with the Philistines, moved the capital from Shechem to Tirzah and attempted to curtail Judah’s trade by building a fort at Ramah. Asa’s strategy (bribing the Syrians to attack on the north) compelled Baasha to abandon his building project and move his men to deal with the Syrians. Elah (877) (Read I Kings 16), Baasha’s son and successor, and all members of Baasha’s family were murdered by Zimri (876*), a chariot commander who had the support of the prophet Jehu. Seven days later Israelite soldiers battling the Philistines elected their field commander Omri (876*) to the kingship. Omri swiftly moved the army to Tirzah, and Zimri, doomed without military support, committed suicide by firing the royal citadel. Another contender for the throne, a certain Tibni, was eliminated. Omri purchased the hill of Samaria and constructed a new capital city. Although Omri’s dynasty is dismissed in a few words by the Deuteronomic editors, perhaps because he was not a Hebrew, his family ruled for three generations and long after the dynasty had ceased Assyrian annalists referred to Israel as "the house of Omri." The Moabite Stone records that Omri expanded Israel’s borders to include northern Moab. Omri’s son Ahab (869), who married Jezebel, a Tyrian princess, receives much more attention for Jezebel brought to Israel the worship of the Tyrian Ba’al, Melkart. Under royal sponsorship the cult flourished, coming into dramatic conflict with Yahwism championed by the prophetic school of Elijah. (Read I Kings 20) War flared between Israel and Syria and, after the defeat of Ben Hadad, Ahab entered into trade agreements with his former enemies and participated in a coalition with Syria and other small nations to halt the westward development of Assyria. According to the records of Shalmaneser V, Ahab contributed 2,000 chariots and 10,000 soldiers. The Assyrians claimed victory at Qarqar. Because the Israelite town of Ramoth-gilead had not been included in the peace settlement of the Syrian-Israelite war, Ahab began a new anti-Syrian campaign with the assistance of Jehoshaphat of Judah (Read I Kings 22). Ahab died in battle and Ahaziah (850) (Read II Kings 1), his son, became king. Injuries suffered in a fall rendered the king powerless to control a revolt by the Moabites; after his death, his brother, Jehoram (849) (Read II Kings 3, 8), continued the war with Moab. Aided by Jehoshaphat of Judah and the Edomites, Jehoram was at first victorious, but Mesha of Moab turned the tide of battle and Moab became an independent kingdom (cf. II Kings 3 and The Moabite Stone). Elijah, the prophet, died during this period and Elisha, his disciple, became "father" or "chief" of the prophetic guild. While Jehoram and Ahaziah of Judah were engaged in battle with the Syrians, Elisha anointed Jehu (842*) king of Israel, thus engendering civil war. Ahaziah of Judah and Jehoram of Israel were killed at Jezreel, and a reign of terror began in which the family of Ahab, including Jezebel, was eliminated and the followers of Ba’al persecuted. Weakened by internal intrigue, Israel was helpless before the power of the Aramaean Kingdom of Hazael, and large amounts of territory were lost in the Transjordan area. Jehoahaz (815), son of Jehu, inherited a nation reduced to impotency by the Aramaeans. Jehoash (801), his son and successor, a more successful warrior, was able to recapture some of the lost land, for King Adadnirari III of Assyria broke the power of Damascus in 800. Jehoash attacked Judah, invaded Jerusalem and looted the temple. During this period Elisha, who appears to have been a friend of the king, died (II Kings 13:14ff.). Jeroboam II (786) (Read II Kings 15), son of Jehoash, was perhaps the most successful warrior king since David, for under his rule Israel gained mastery over Syria and Moab to control an area approximating that embraced at the time of the Davidic empire (minus, of course, Judah, Edom and Philistia). Fortunately, Jeroboam was not troubled by the Assyrians and his reign, marked by prosperity and wealth, provides a social background against which some of the prophetic utterances of Amos and Hosea must be understood. Zechariah (746), son of Jeroboam, reigned less than one year and was murdered by Shallum (745*), who was promptly killed by Menahem (745*). To prevent conquest by Assyria, Menahem voluntarily submitted to Tiglath Pileser III (Pul) and paid heavy tribute, a detail confirmed in an Assyrian text. Shortly after Pekahiah (738), son of Menahem, became king, he was murdered by his captain, Pekah (737*) (Read II Kings 16-17). At this time participation in a political alliance against Assyria cost Israel the loss of towns in northern Galilee and Gilead. Pekah’s murderer and successor Hoshea (732*) seized the moment of the death of Tiglath Pileser III and the ascension of Shalmaneser V to the Assyrian throne as the time to throw off the Assyrian yoke. Counting on help from Egypt, Hoshea refused to pay tribute to Assyria. Shalmaneser attacked Samaria but died while the siege was still in process, leaving the subjugation of Israel to his successor, Sargon II (722) . When Samaria fell in 721 and all Israel capitulated, great numbers of the people (according to Sargon, 27,290) were deported to the Assyrian province of Guzanu and to the region south of Lake Urmia. From other parts of the farflung Assyrian empire, emigrants were brought to Israel. Israel’s history as an independent nation had terminated. Sargon divided the territory into small provinces. Revolts were abortive. Among those Israelites who remained in the land, the worship of Yahweh continued, but homage was paid to the gods of Assyria. |

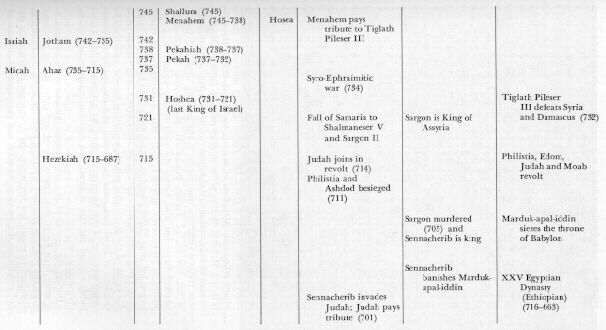

AN ARTIST’S RIECONSTRUCTION OF TELL EN-NASBEH. Tell en-Nasbeh, excavated between 1926 and 1935 by Dr. William F. Badè of the Pacific School of Religion, is believed to be the site of ancient Mizpah, the city fortified by King Asa of Judah. The massive walls were thirteen to twenty feet thick and probably forty feet high. The single, strongly fortified gate had a paved, drained forecourt with benches where the elders of the city might have sat to render judgment (cf. Amos 5:15; Ruth 4:11; Prov. 31:23).

AN ARTIST’S RIECONSTRUCTION OF TELL EN-NASBEH. Tell en-Nasbeh, excavated between 1926 and 1935 by Dr. William F. Badè of the Pacific School of Religion, is believed to be the site of ancient Mizpah, the city fortified by King Asa of Judah. The massive walls were thirteen to twenty feet thick and probably forty feet high. The single, strongly fortified gate had a paved, drained forecourt with benches where the elders of the city might have sat to render judgment (cf. Amos 5:15; Ruth 4:11; Prov. 31:23).

A MODEL OF A SECTION OF MEGIDDO IN THE TIME OF AHAB. The low structures on the right, just inside the city wall, are stables capable of housing 450 horses. The open area in front of the stables represents an exercise or parade ground. The large pit to the right and outside of the stable area marks the entrance to an underground passage leading to a spring, the water supply for the city. In the background, the impressive structure with the tower is a model of the governor’s palace with a private walled court, and the size and magnificence of this building testifies to the affluence of Ahab’s day. The circular structure outside of the courtyard is a storage pit for grain. The outline of walls and buildings in the foreground represents structures from the older Canaanite layers of habitation that archaeologists found beneath the ninth century levels.

A MODEL OF A SECTION OF MEGIDDO IN THE TIME OF AHAB. The low structures on the right, just inside the city wall, are stables capable of housing 450 horses. The open area in front of the stables represents an exercise or parade ground. The large pit to the right and outside of the stable area marks the entrance to an underground passage leading to a spring, the water supply for the city. In the background, the impressive structure with the tower is a model of the governor’s palace with a private walled court, and the size and magnificence of this building testifies to the affluence of Ahab’s day. The circular structure outside of the courtyard is a storage pit for grain. The outline of walls and buildings in the foreground represents structures from the older Canaanite layers of habitation that archaeologists found beneath the ninth century levels.

A MANGER FROM THE MEGIDDO STABLES. The holes in the upright pillars were for tethering the horses.

A MANGER FROM THE MEGIDDO STABLES. The holes in the upright pillars were for tethering the horses.

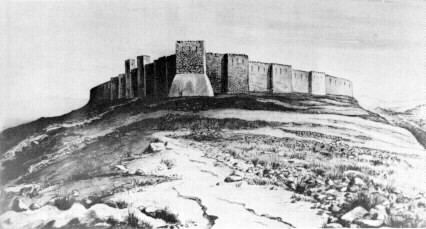

THE MOABITE STONE,which dates from the ninth century B.C., was discovered at the site of ancient Dibon in 1868 by the Rev. F. A. Klein, a German missionary. Fortunately a squeeze or impression was made by pressing soft, moist, paper-pulp tightly against the inscription and permitting it to dry before removal, thus giving a precise copy, for shortly afterward the stone was smashed by bedouin who hoped to get a better price by disposing of the pieces individually. Some parts were lost but the remainder were acquired for the Louvre by Charles Clermont-Ganneau, the French Orientalist. With the aid of the squeeze, it was possible to restore the original text.

THE MOABITE STONE,which dates from the ninth century B.C., was discovered at the site of ancient Dibon in 1868 by the Rev. F. A. Klein, a German missionary. Fortunately a squeeze or impression was made by pressing soft, moist, paper-pulp tightly against the inscription and permitting it to dry before removal, thus giving a precise copy, for shortly afterward the stone was smashed by bedouin who hoped to get a better price by disposing of the pieces individually. Some parts were lost but the remainder were acquired for the Louvre by Charles Clermont-Ganneau, the French Orientalist. With the aid of the squeeze, it was possible to restore the original text.

The stone is black basalt and is three feet ten inches high, two feet wide, and fourteen inches thick. There are thirty-four lines of script of a dialect closely resembling Hebrew. The account, written in the first person singular, supplements the biblical history of Israel from the time of Omri to Ahaziah. Like the Hebrews the Moabites attributed military success or failure to their god. The first twenty lines are reproduced below.

I (am) Mesha, son of Chemosh king of Moab, the Dibonite–my father (had) reigned over Moab thirty years, and I reigned after my father,–(who) made this high place for Chemosh in Qarhoh [. . .] because he saved me from all the kings and caused me to triumph over all my adversaries. As for Omri, (5) king of Israel, he humbled Moab many years (lit., days), for Chemosh was angry at his land. And his son followed him and he also said, "I will humble Moab." In my time he spoke (thus), but I have triumphed over him and over his house, while Israel hath perished for ever! (Now) Omri had occupied the land of Medeba, and (Israel) had dwelt there in his time and half the time of his son (Ahab), forty years; but Chemosh dwelt there in my time.

And I built Baal-meon, making a reservoir in it, and I built (10) Qaryaten. Now the men of Gad had always dwelt in the land of Ataroth, and the king of Israel had built Ataroth for them; but I fought against the town and took it and slew all the people of the town as satiation (intoxication) for Chemosh and Moab. And I brought back from there Arel (or Oriel), its chieftain, dragging him before Chemosh in Kerioth, and I settled there men of Sharon and men of Maharith. And Chemosh said to me, "Go, take Nebo from Israel!" (15) So I went by night and fought against it from the break of dawn until noon, taking it and slaying all, seven thousand men, boys, women, girls and maid-servants, for I had devoted them to destruction for (the god) Ashtar-Chemosh. And I took from there the […] of Yahweh, dragging them before Chemosh. And the king of Israel had built Jahaz, and he dwelt there while he was fighting against me, but Chemosh drove him out before me. And (20) 1 took from Moab two hundred men, all first class (warriors), and set them against Jahaz and took it in order to attach it to (the district of) Dibon.

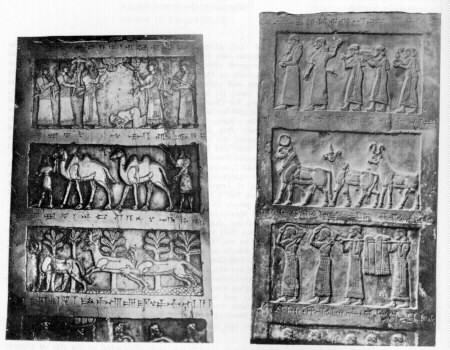

JEHU PAYS TRIBUTE.In 1846 during the excavation of the ancient city of Calah, Austin Henry Layard discovered a four-sided pillar or obelisk of black limestone, six and one half feet high. Five panels of bas reliefs extended around the pillar with an accompanying cuneiform description of the reliefs. The pillar commemorated the achievements of Shalmaneser III during the thirty-five years of his reign. In the top panels pictured above, Jehu or his representative is pictured kneeling before Shalmaneser, and the second panel at the top shows a group of Israelites bearing tribute. Some features of Israelite dress can be discerned: they wore soft caps, sleeveless fringed tunics, and had rounded beards. The taller, armed figures are Assyrians. The inscription pertaining to Jehu reads: "The tribute of Jehu, son of Omri: I received silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden vase, golden goblets, golden pitchers, tin, a scepter for the king, and staves." Identifying Jehu as a "son of Omri" must be understood as "successor to Omri" and also as a sign of the importance of Omri’s reign. The lower panels represent tribute from other parts of the Assyrian empire.

JEHU PAYS TRIBUTE.In 1846 during the excavation of the ancient city of Calah, Austin Henry Layard discovered a four-sided pillar or obelisk of black limestone, six and one half feet high. Five panels of bas reliefs extended around the pillar with an accompanying cuneiform description of the reliefs. The pillar commemorated the achievements of Shalmaneser III during the thirty-five years of his reign. In the top panels pictured above, Jehu or his representative is pictured kneeling before Shalmaneser, and the second panel at the top shows a group of Israelites bearing tribute. Some features of Israelite dress can be discerned: they wore soft caps, sleeveless fringed tunics, and had rounded beards. The taller, armed figures are Assyrians. The inscription pertaining to Jehu reads: "The tribute of Jehu, son of Omri: I received silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden vase, golden goblets, golden pitchers, tin, a scepter for the king, and staves." Identifying Jehu as a "son of Omri" must be understood as "successor to Omri" and also as a sign of the importance of Omri’s reign. The lower panels represent tribute from other parts of the Assyrian empire.

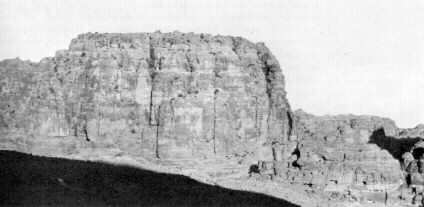

ANCIENT SELA. The massive stone outcropping rising 950 feet above the floor of the valley at Petra and known today as Umm el-Biyerah ("mother of cisterns") because of the numerous cisterns carved in its surface, is believed to be the site of ancient Sela. The approach to the summit is by a narrow trail which winds up the steep sides to the acropolis. If this is the site of Sela, the Hebrew conquest of the unapproachable site was an amazing feat. Here Amaziah defeated the Edomites (II Kings 14:7), and if the account in II Chron. 25:11 ff. is accurate, it is here that 10,000 Edomites died after being hurled from "the top of the rock."

ANCIENT SELA. The massive stone outcropping rising 950 feet above the floor of the valley at Petra and known today as Umm el-Biyerah ("mother of cisterns") because of the numerous cisterns carved in its surface, is believed to be the site of ancient Sela. The approach to the summit is by a narrow trail which winds up the steep sides to the acropolis. If this is the site of Sela, the Hebrew conquest of the unapproachable site was an amazing feat. Here Amaziah defeated the Edomites (II Kings 14:7), and if the account in II Chron. 25:11 ff. is accurate, it is here that 10,000 Edomites died after being hurled from "the top of the rock."

Old Testament Life and Literature is copyright © 1968, 1997 by Gerald A. Larue. All rights reserved.

The electronic version is copyright © 1997 by Internet Infidels with the written permission of Gerald A. Larue.