The First Coming: How the Kingdom of God Became Christianity (1986–electronic edition 2000)

Thomas Sheehan

II

How Jesus Was Raised From the Dead

Soon after Jesus died, something dramatic happened to his reputation: His followers came to believe that he had been raised from the dead and was alive with his heavenly Father. This enhancement of Jesus’ reputation is a historical fact, observable by anyone who studies the relevant documents.

But according to Christians, something dramatic happened not just to Jesus’ reputation but above all to Jesus himself. They believe he actually was raised from the dead, was taken into heaven, and is now reigning there as the equal of God the Father. These, however, are not observable historical facts but claims of faith.

The purpose of this central part of our study is to distinguish between the facts of history and the claims of faith, between what certainly happened to Jesus’ reputation after he died and what allegedly happened to Jesus himself. There is no doubt that Christianity formally began with the disciples’ claim that Jesus had been rescued from death. Our question, however, is what that claim meant in the early church and what historical experiences lay behind it. (When speaking of resurrection, the New Testament writers generally use the passive

92

construction “Jesus was raised [by God]”–in Greek êgerthê or egêgertai--rather than the active-voice “Jesus rose” [anestê]. In what follows I use the word “resurrection” in the New Testament’s passive sense: Jesus’ “being-raised” by God.[1])

Here, in the search for the historical origins of Christian faith in the resurrected Jesus, what I said in the [Introduction] holds especially true: I rely upon the scientifically controllable results of contemporary Christian exegesis of the New Testament texts that bear upon the resurrection. However, I also go beyond that exegesis by using its results as data for my own interpretation.

The last event in Jesus’ life was his death, but even in death his fame began to grow. We now study the first stirrings of the movement that transformed Jesus, in the eyes of his followers, from the crucified prophet into the ruling Son of God. First, under the rubric of “Simon’s Experience,” we investigate the scriptural claim that Jesus appeared to Simon Peter after the crucifixion. Second in “The Empty Tomb,” we study the story in Mark’s Gospel that Jesus’ tomb was found empty on Easter Sunday morning.

93

SIMON’S EXPERIENCE

95

1. The Myth of Easter

Popular Christian piety holds that Jesus’ existence on earth extended beyond his death on Good Friday and spilled over into a miraculous six-week period that stretched from his physical emergence from the tomb on Easter Sunday morning, April 9, 30 C.E., to his bodily ascension into heaven forty days later, on Thursday, May 17, 30 C.E.[2]

To judge from the Gospels, it would seem that the activities of the risen Jesus during the forty days after he died included: one breakfast; one and a half dinners; one brief meeting in a cemetery (in fact with his clothes off: John 20:6, 14);[3] two walks through the countryside; at least seven conversations (including two separate instructions on how to forgive sins and baptize converts)–all of this climaxing in his physical ascension into heaven from a small hill just outside Jerusalem. Impossible though the task is, if we were to try to synthesize the gospel stories into a consistent chronology of what Jesus did during those hectic six weeks between his resurrection from the dead and his ascension into heaven, the agenda would look something like this:

96

SUNDAY, APRIL 9, 30 C.E.: THE JERUSALEM AREA

| MORNING

1. Jesus rises from the dead early in the morning (Mark 16:9). Mary Magdalene, alone or with other women, discovers the open tomb. Either she informs Peter and another disciple, who visit the tomb and find it empty (John 20:1-10); or she and the others meet one or two angels inside, who announce the resurrection (Mark 16:5-6; Luke 24:4-6). 2. Later, outside the tomb, Jesus appears to Mary Magdalene alone, who at first mistakes him for a gardener. He tells her to inform the disciples that he is ascending at that moment to his Father (John 20:17; Mark 16:9). 3. Jesus also appears to Mary Magdalene and another Mary, who grasp his feet and worship. Jesus tells them to send the brethren to Galilee, where they will see him (Matthew 28: 10). 4. Sometime during the day Jesus appears to Simon Peter (Luke 24:34). AFTERNOON AND EARLY EVENING 5. Jesus walks incognito through the countryside for almost seven miles with two disciples. He starts to eat dinner with them in Emmaus but disappears as soon as they recognize who he is (Luke 24:13-31; Mark 16:12-13). EVENING 6. Back in Jerusalem, Jesus appears to the disciples in a room even though the doors are locked. He tries to overcome their doubts by showing them his wounds and by eating broiled fish and honeycomb. He either gives them the Holy Spirit and the power to forgive sins (John) or does not (Luke), and either sends them out into the whole world (Mark) or tells them to stay in Jerusalem for a while (Luke). The disciple Thomas either is present (Luke and Mark, by implication) or is not (John). (Luke 24:36-49; John 20:19-23; Mark 16:14-18). 7. Jesus ascends into heaven that night from Bethany (Luke 24:51; Mark 16:19). |

SUNDAY, APRIL 16, 30 C.E.: STILL IN JERUSALEM

| 8. Jesus appears again to the disciples behind locked doors, and invites Thomas, who now is present, to put his fingers and hands into the wounds (John 20:26-29).

|

OVER THE NEXT WEEKS

| 9. Jesus offers the disciples many other proofs and signs, not all of which are recorded in the Gospels (John 20:30).

|

97

LATE APRIL OR EARLY MAY, 30 C.E.: GALILEE

| 10. Early one morning Jesus makes his “third appearance” (sic, John 21:14), this time to Simon and six others on the shore of Lake Galilee. He miraculously arranges for them to catch 153 large fish and invites them ashore for a breakfast of broiled fish and bread, which he has prepared. Jesus instructs Simon, “Feed my lambs, feed my sheep,” and discusses how Simon and the Beloved Disciple will die (John 21:1-23).

11. Jesus appears to the eleven disciples on a mountain, but some still doubt. He commissions them to baptize all nations and assures them, “I am with you always, to the close of the age.” He does not ascend into heaven (Matthew 28:16-20) |

THURSDAY, MAY 17, 30 C.E.: BACK IN THE JERUSALEM AREA

| 12. Jesus appears again and tells the disciples to wait in Jerusalem until they receive the Holy Spirit (even though, according to John, they had already received the Spirit on April 9: John 20:22). Then he ascends into heaven from Mount Olivet, just west of Jerusalem (Acts 1:1-12).

|

SUNDAY, MAY 27, 30 C.E.: JERUSALEM

| 13. God sends the Holy Spirit upon the twelve disciples, Mary the mother of Jesus, and about 107 other people (Acts 2:1-4; cf 1:13-15, 26).

|

It is clear that the scriptural stories about this six-week period contradict one another egregiously with regard to the number and places of Jesus’ appearances, the people who were on hand for such events, and even the date and the location of the ascension into heaven. Despite our best efforts above, the gospel accounts of Jesus’ post mortem activities in fact cannot be harmonized into a consistent “Easter chronology.” Nor need we bother to ask if the miraculous events of this Easter period could have been observed or recorded by cameras or tape recorders, had such devices been available. The reasons both for the patent inconsistencies and the physical unrecordability of these miraculous “events” come down to one thing: The gospel stories about Easter are not historical accounts but religious myths.[4]

I say this not at all out of disrespect for Christian faith or for the

98

doctrines that it holds. Rather, I mean to indicate the general literary form of the Easter accounts. They are myths and legends; and it is absurd to take them literally and to create a chronology of preternatural events that supposedly occurred in Jerusalem and Galilee during the weeks after Jesus had died. My purpose here is not to undo the meaning of Easter but precisely to reconstruct it by interpreting the myths that have been used to express that meaning.

In anticipation of what we shall see later, it is worth noting at this point that the New Testament does not in fact assert that Jesus came back to life on earth, or that he physically left his grave after he had died, or that faith in him is based on an empty tomb. What is more, almost forty years would pass after Jesus’ death before the Christian Scriptures so much as mentioned an empty tomb (Mark 16:6, written around 70 C.E.), and it would take yet another fifteen years after that (ca. 85 C.E.) before the Gospels of Matthew and Luke would claim that Jesus’ followers had seen and touched his risen body. I hope to show that (1) even though Jesus’ tomb was probably found empty after his death, that fact says nothing about a possible resurrection; and (2) the stories about Jesus showing his disciples his crucified-and-risen body are relatively late-arriving legends in the Christian Scriptures and in the final analysis are not essential to Christian faith.

But if Christianity stands or falls with the resurrection, may we ask “when” Jesus was raised from the dead? The Scriptures make no attempt to date the resurrection to Easter Sunday morning, nor do they claim that anyone saw it happen.[5] They do not even assert that the resurrection took place at Jesus’ tomb. In fact, catechetical popularizations aside, the church does not claim that the resurrection was a historical event, a happening in space and time.

Nonetheless, about 150 years after Jesus’ death the so-called Gospel of Peter (an apocryphal work which the church does not accept as authentic Scripture) did offer what purports to be an eyewitness account of what happened at Jesus’ grave on the first Easter. The narrative has had considerable influence on Christian iconography, but all that notwithstanding, the story remains pure legend.[6]

According to the Gospel of Peter the resurrection took place during the Saturday night after the crucifixion. As the legend tells it, the drama started with a loud voice that rang out from heaven and startled

99

the soldiers who were guarding Jesus’ tomb. Then the extraordinary action began:

They [the soldiers] saw the heavens open and two men [angels] come down from there in a great brightness and draw nigh to the sepulcher. The stone that had been laid against the entrance to the sepulcher began to roll by itself and gave way to the side. The sepulcher was opened, and both the young men entered in. (8:36-37)

The soldiers, understandably taken aback by all of this, awaken the Jewish elders who are also guarding the grave, and the group witnesses a spectacular procession featuring a giant-sized Jesus and two only slightly shorter attendants.

And they saw three men come out of the sepulcher, two of them [the angels] sustaining the other [Jesus], while a cross followed them, the heads of the two reaching to heaven, but the head of [Jesus, whom] they were leading by the hand overpassing the heavens.

And they heard a voice out of the heavens crying, “Thou hast preached to them that sleep.” And from the cross was heard the answer, “Yes.” (8:39-42)

The tale continues in an equally fanciful vein, but the point is clear: This eyewitness account of the resurrection is a myth. Nonetheless, the fiction is correct in at least one matter: If any witnesses had observed such a bizarre scene, it would have convinced them of absolutely nothing relevant to Christian faith. According to the Gospel of Peter, the Roman soldiers and Jewish elders who allegedly saw the resurrection did not thereby become believers but rather ran off in confusion and reported the scene to Pilate. In other words, whatever religious intentions moved the author of the apocryphal book to concoct this graphic description of the resurrection, the text itself shows that physically witnessing Jesus’ alleged emergence from the tomb on Easter Sunday morning would not have moved anyone to believe. As we shall see later, the Gospels of Mark and John show that the sighting of an empty tomb by women on Easter Sunday morning neither provided them with evidence of a resurrection nor motivated them to believe

100

in it. But the Gospel of Peter shows that even viewing the resurrection (if that were possible) would not of itself elicit Christian faith.[7]

Quite apart from the apocryphal Gospel of Peter, the accepted scriptural accounts of Easter are themselves riddled with contradictions, as we saw above–proof, according to the village atheist, that the Gospels are frauds, and evidence, according to the fundamentalist believer, that God is indeed mysterious. But the naive historical positivism that characterizes both camps is simply a category mistake–like looking up “poetry” in the dictionary and expecting to find rhyming verse, or searching for mathematics in the phone book because it is full of numbers. Both sides miss the point of the apocalyptic literary forms in which the writers of the New Testament couched early Christian faith–a matter to which we shall return.

Granted that the gospel accounts of Easter are myths rather than historical accounts, what actually did happen after the crucifixion? Bereft as we are of historical access to the “resurrection,” we find ourselves thrown back on the claims of Simon Peter and other early believers that they had certain supernatural experiences (“appearances”) which convinced them that Jesus was alive after his death. The first recorded claim of such appearances (I Corinthians 15:5-8) was not written down until some twenty-five years after the crucifixion; we shall turn to that text in a moment. First, however, let us attempt to reconstruct the historical events that actually took place in the days and weeks after Jesus died.

101

2. The Birth of Christianity

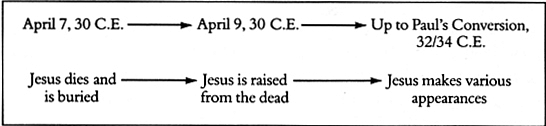

The last historical event in the life of Jesus of Nazareth was his death on April 7, 30 C.E., following the torture of crucifixion. No coroner was present to record the medical facts, but the Scriptures and the Christian creed put the matter simply and directly: He died and was buried.

Jesus had not fainted. He was dead. And in the spirit of the New Testament we may add: He never came back to life.[8]

As a deterrent to crime the Roman authorities usually left the bodies of the crucified hanging on the cross until they had decomposed, but in Palestine this practice was suspended out of respect for a Jewish law that mandated the burial of a hanged man on the day of his death.[9] As criminals, the victims of crucifixion were usually buried in a common grave rather than in individual tombs, and Jesus’ corpse may have suffered that fate. This possibility is increased by the fact that the Jewish law considered hanged or crucified men to be accursed by God (Deuteronomy 21:23; cf. Galatians 3:13).[10] In fact, one scripture text indicates that Jesus was buried not by his disciples but by his enemies, the very ones who had arranged for his death (“those who live in Jerusalem and their rulers,” Acts 13:27, 29). This rough burial would

102

thus have constituted the final rejection of the prophet by those to whom he had preached.

On the other hand, there may well be historical truth to the gospel stories that before evening fell and the Passover began, Joseph of Arimathea, a member of the Sanhedrin, removed the body from the cross with Pilate’s permission, wrapped it in linen cloths, and sealed it in a tomb hewn out of rock.[11](Matthew’s story that the high priests set guards the next day at Jesus’ tomb is a later legend, as we shall show below.)

The Passover festival of 30 C.E. came and went, and life returned to normal. Caiaphas and the Sanhedrin, no doubt with some remorse over the brutal turn of events, went back to their religious duties. Pilate and the Roman garrison breathed more easily as the pilgrims poured out of Jerusalem and the city resumed the routine of everyday life.[12] Across Palestine farmers began the spring planting, workers pursued their trades, Zealots continued to hatch their revolutionary plots against the Roman Empire.

Jesus’ closest disciples probably knew of the prophet’s death only by hearsay. Most likely they had not been present at the crucifixion and did not know where he was buried. Having abandoned Jesus when he was arrested, they had fled in fear and disgrace, probably immediately to Bethany, where they had been living with Jesus in the previous days, and then a few days later to their homes in Galilee. There, grieving at their loss and struggling to pick up the scattered bits of their lives, they faced the crushing scandal of those last days in Jerusalem.[13]

The scandal was not that God’s eschatological prophet had been condemned to die on the cross. Traumatic as it was for the disciples, the murder of Jesus was not entirely a surprise; indeed, it seemed to be almost inevitable. Death was the price that prophets had long paid (John the Baptist was only the most recent case) for threatening the tidy, cherished world of the religious establishment and the vaunted omnipotence of empire. Jesus had known what was in store for him, and he accepted it with courage. By proclaiming the revolution of God-with-man to people who preferred the security of religion and power, he had sealed his fate.

But he had also secured his reward. By trusting himself entirely to the present-future, by giving himself without reserve to the cause of God-with-man–that is, by living the kingdom and becoming what

103

he lived–Jesus proclaimed that not even the grave could cancel God’s presence. “You will not abandon my soul to hell, you will not let your holy one see corruption” (Psalm 15:10; Acts 2:27). This is what Jesus finally meant by “Abba”: that everything, even death, was in the hands of his loving Father, with whom he was as one.

Thus, as Jesus prepared the disciples for his inevitable fate, they came to believe, even before the crucifixion, in a higher inevitability: No matter what happened, God would have to awaken his servant from the sleep of the tomb and take him into heavenly glory (Mark 8:31; Luke 24:26).

No, the scandal of those last days in Jerusalem was not that the prophet was crucified, but that the disciples lost faith in what he had proclaimed. Jesus’ every word had been a promise of life, but they fled when threatened with death. He had trusted utterly in God; but they feared men. On the night before Passover, they abandoned the prophet to his enemies, just after sharing with him the cup of a fellowship that was supposed to be stronger than death.

We may imagine the disciple Simon, later to be called Cephas or Peter–a fisherman perhaps thirty years of age–now returned to Capernaum, his village on the Sea of Galilee.[14] He thinks of the prophet, his friend, whose body is rotting in a grave outside Jerusalem. He recalls their last meal together.

Simon declared to Jesus, “Though they all fall away because of you, I will never fall away!” Jesus said to him, “Truly, I say to you, this very night, before the cock crows, you will deny me three times.” Simon said to him: “Even if I must die with you, I will not deny you.” (Matthew 26:33-35)

Simon remembers the darkness of Gethsemane that same night as Jesus went ahead into the grove to pray. Suddenly the arrival of armed men, the torchlight red on sweaty faces, a kiss of betrayal. Then the cowardly flight through the olive grove and away into the night.

But Simon followed Jesus at a distance, as far as the courtyard of the high priest, and going inside, he sat with the guards to see the end.

104

And a maid came up to him and said, “You also were with Jesus the Galilean.” But he denied it before them all: “I do not know the man.

When he went out to the gateway, another maid saw him and said to the bystanders, “This man was with Jesus of Nazareth.” And again he denied it with an oath, “I do not know the man!”

After a while the bystanders came up and said to Simon, “Certainly you are one of them, for your accent betrays you.” Then he began to invoke a curse on himself and to swear, “I do not know the man!”

And immediately the cock crowed, and Simon remembered the saying of Jesus, “Before the cock crows, you will deny me three times.” And he went out and wept bitterly. (Matthew 26:58, 69-75)

Jesus had said, “if the light inside you is darkness, what darkness that will be!” (Matthew 6:23).There in Capernaum Simon, the young fisherman, felt that inner darkness: It was like being storm-tossed on the night sea, when the savage waves lash your face and you watch helplessly as the sail tears loose from the mast and the rudder breaks free of your grasp. You are lost and there is nothing to do. [15]

Then Jesus, followed by his disciples, got into the boat, and without warning a storm broke over the lake, so violent that the waves were crashing right over the boat. But Jesus was asleep. So they ran to him and shook him awake, saying, “Save us, Lord, we’re going under!” (Matthew 8:23-26; cf. 14:28-33)

In those dark days after Jesus’ death, Simon had an insight, a “revelatory experience” that he took as a message from God’s eschatological future.[16]

We cannot know exactly how the insight dawned on him. But we do know that the spirit of apocalypse was in the air and that Simon had breathed it deeply. He was convinced that these were the final days before the end, and he knew that God had promised:

In the last days

__ I will pour out my Spirit on all flesh,

105

And your sons and daughters shall prophesy,

__ and your young men shall see visions. (Joel 2:28)

In the apocalyptic spirit of the times, pious Jews felt at home with a broad spectrum of ecstatic visions and eschatological manifestations: theophanies (Acts 7:55), angelophanies (Luke 1:11), revelations (Galatians 1:12),epiphanies of returning prophets (Mark 8:28),and stories about how Gentiles had converted to Judaism after having visions of blinding light (the way Saint Paul turned to the Jesus-movement: cf. Acts 9:3).It was this lexicon of apocalyptic revelations that Simon spontaneously drew upon when he first tried to put into words the “Easter experience” that he had undergone there in Capernaum.[17]

Simon hastened to share his experience with Jesus’ closest followers. He gathered them together at his house, to reflect on what they had earnestly hoped for and to renew their faith. They spoke of their master, recalled his extraordinary message, and prayed his eschatological words: “Abba, thy kingdom come!”

Simon told them his Easter experience: In his despair, when he felt like a drowning man pulled to the bottom of the sea, the Father’s forgiveness, that gift of the future which was God himself, had swept him up again and undone his doubts. Simon “saw”–God revealed it to him in an ecstatic vision–that the Father had taken his prophet into the eschatological future and had appointed him the Son of Man. Jesus was soon to return in glory to usher in God’s kingdom!

And having “turned again” under the power of God’s grace, Simon “strengthened the brethren” (Luke 22:32). Jesus’ disciples began to call him “Simon Kepha,”therock of faith. They clung to that rock, and they too sensed the gift of God’s future undoing their lack of faith. They too “saw” God’s revelation and had the Easter experience.[18]

There in Capernaum–without having laid eyes on Jesus since the moment he was dragged off to his trial, without seeing Jesus’ tomb in Jerusalem or hearing that it was supposedly empty[19]–Simon and the other disciples experienced Easter. We cannot know with certainty the psychological genesis of that experience, but we do know its result. They believed that Jesus had been designated the coming Son of Man. God’s reign would soon be realized.

The Jesus-movement was born–or rather, reborn–and it came forth proclaiming the message of the prophet in the same synagogues

106

of Capernaum, Chorazin, and Bethsaida where he himself had preached it. “Repent!” they exhorted the people. “The kingdom of God is at hand!”[20]

How did Simon (and the other disciples) put the Easter experience into words?[21] We should not conclude too hastily that Simon proclaimed that Jesus had been physically raised from the dead. The “resurrection” was not a historical event but only one possible way, among many others, in which Simon could interpret the divine vindication of Jesus that he claimed to have experienced.[22] In fact, “resurrection” was probably not the first term that he used to express what he had “seen.” Probably the earliest way that Simon put into words his renewed faith in God’s kingdom was to say that God had “glorified” his servant (Acts 3:13), that he had “exalted” him to his right hand (2:33), that he had assumed him into heaven and “designated” him the agent of the coming eschaton (3:20)–without any mention of a physical resurrection. Later believers would say merely that Jesus had “entered heaven” and “appeared before God” (Hebrews 9:24) or simply that he was “alive” (Acts 1:3). Simon and the disciples probably used all these ways to express their Easter experience, the revelation that Jesus had been rescued from death and appointed God’s eschatological deputy.[23]

Of course, the language of resurrection was also available, but in the apocalyptic context of the times a resurrection did not necessarily mean that a dead person came back to life and physically left his grave. Some rabbis, to be sure, did promise a dramatically physical resurrection at the end of time, when bodies would return with the same physique that they formerly had (including blemishes) and even with the same clothes. But these fanciful hopes were only one part of the broad spectrum of eschatological hopes, which included as well the promise of resurrections that entailed no vacating of the gravel.[24]

The Gospels, for example, say that Herod Antipas thought Jesus was really John the Baptist raised from the dead (cf. mark 6:16). Today we might suggest that the tetrarch could have allayed his fears by making a trip to the Dead Sea and having John the Baptist’s body exhumed. But that thought probably did not even occur to Herod, any more than it occurred to Simon to go down to Jerusalem from Galilee to check whether Jesus’ bones were still in the tomb. In first-century Palestine, belief in a resurrection did not depend on cemetery records

107

and could not be shaken by exhumations or autopsies. Resurrection was an imaginative, apocalyptic way of saying that God saved the faithful person as a whole, however that wholeness be defined (see, for example, I Corinthians 15:35ff.). Resurrection did not mean having one’s molecules reassembled and then exiting from a tomb.

Regardless of whether Simon used the apocalyptic language of exaltation or of resurrection to express his identification of Jesus with God’s coming kingdom, neither of these symbolic terms committed Simon to believing that Jesus went on existing or appearing on earth after his death. Affirmations of resurrection or even appearances are not statements about the post mortem history of Jesus but religious interpretations (in fact, secondary ones) of Simon’s Easter experience. And for Christianity, Simon’s experience is the first relevant historical event after the death and burial of Jesus.[25]

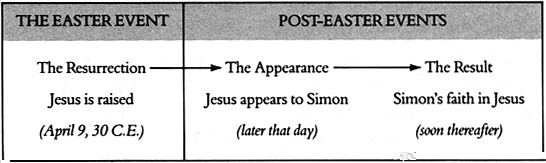

In other words, according to the popular and mythical “Easter chronologies” that some Christians try to establish from the Gospels, the putative order of events after the crucifixion is as follows:

However, the actual sequence of events after the death of Jesus seems to be quite different, and on our hypothesis would look like the following:

108

Some remarks are in order about this second–and, I maintain, correct–hypothesis concerning the sequence of “Easter events.”[26]

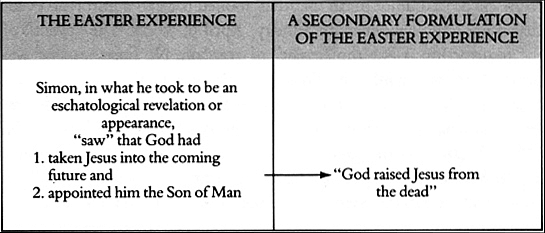

THE EASTER EXPERIENCE: Something happened to Simon and the other disciples in the order of space and time, perhaps even over a period of time–an experience that could have been as dramatic as an ecstatic vision, or as ordinary as reflecting on the meaning of Jesus. In any case it was an experience to which no one else, whether believer or nonbeliever, could have direct, unmediated access. In fact, not even Simon could claim unmediated access to the experience he underwent: He knew it only by interpreting it. Eventually Simon and/or the others would speak of his experience in one of the many apocalyptic symbols that were at hand: “Jesus has appeared to Simon.” As we shall see below, such an appearance need not have been a physical-ocular manifestation of Jesus. Simon understood his experience as an eschatological revelation that Jesus had been appointed the coming Son of Man. Simon now believed that God had taken his prophet into the eschatological future and would send him at the imminent end of time to usher in the kingdom.

A SECONDARY FORMULATION OF THE EASTER EXPERIENCE: The rescue of Jesus from death and his exaltation to the status of Son of Man soon came to be codified in yet another of the available apocalyptic formulae: “God has raised Jesus from the dead.” Eventually “resurrection” became the dominant and even normative term for expressing what Simon and the disciples believed had happened to Jesus.[27]

But even then, for the early believers to speak of Jesus’ resurrection from the dead did not mean that they looked back to a historical event that supposedly happened on Sunday, April 9, 30 C.E. The “event” of the resurrection is like the “event” of creation: No human being was present, no one could or did see it, because neither “event” ever happened. Both creation and the resurrection are not events but interpretations of what some people take to be divine actions toward the world. Thus, all attempts to “prove the resurrection” by adducing physical appearances or the emptiness of a tomb entirely miss the point. They confuse an apocalyptic symbol with the meaning it is trying to express. For Simon and the others, “resurrection” was simply one way of

109

articulating their conviction that God had vindicated Jesus and was coming soon to dwell among his people. And this interpretation would have held true for the early believers even if an exhumation of Jesus’ grave had discovered his rotting flesh and bones.[28]

In short, the grounds for Simon’s Easter faith were neither the discovery of an empty tomb (Simon most likely did not know where the prophet was buried) nor the physical sighting of Jesus’ risen body (this is not what an eschatological appearance is about). Easter happened when Simon had what he thought was an eschatological revelation, which overrode his doubts and led him to identify Jesus with the coming Son of Man.[29]

What I have stated thus far is obviously a hypothesis, and the question now is whether the Scriptures support such an interpretation or whether it too is only a fanciful reconstruction with no more basis than the mythical “Easter chronologies.” To test the hypothesis, we must turn to the New Testament texts. As we noted earlier, the first recorded mention of Simon’s experience was written down twenty-five years after the fact. The claim is found in an epistle of Paul, an itinerant Jewish evangelist who had converted to the Jesus-movement a few years after the crucifixion. Let us turn now to Paul’s text in order to see how he interpreted Simon’s experience.

110

3. An Early Formula of Faith

Within a few years of Jesus’ death a kerygma (a proclamation of faith in Jesus) began to circulate in certain synagogues of Palestine and Syria. It declared that Jesus, having died and been buried, had been raised up on the third day and–here was the first mention of it–had appeared to his followers. Paul himself learned the formula soon after he joined the Jesus-movement around 32-34 C.E., and he both recorded and expanded it in his First Letter to the Corinthians, which he dictated some twenty years later, around 55 C.E.[30]

In its expanded form, Paul’s kerygma went beyond the mere statement that Jesus had appeared. It went on to list those who had experienced an appearance of Jesus. Stated in direct discourse, the expanded kerygma that Paul recorded in First Corinthians declared that Jesus

died for our sins

__ in accordance with the Scriptures,

and was buried.

111

And he was raised on the third day

__ in accordance with the Scriptures,

and appeared to Cephas

__ and then to the Twelve.Afterward he appeared to more than five hundred brethren,

__ most of whom are still alive, though some have fallen asleep.Afterward he appeared to James,

__ and then to all the missionaries.Last of all, as to one untimely born,

__ he appeared also to me. (I Corinthians 15:3-8)

This formula, which is among the earliest written statements of Christian faith, is striking for one thing that it does not say: It neither mentions nor presumes the discovery of an empty tomb on Easter Sunday morning. The kerygma says merely that Jesus “was raised”–that is, was taken up (in whatever fashion) into God’s eschatological future–but not that he physically came out of his grave. Paul does not mention the empty tomb in any of his writings, and it is far from clear that he even knew of it. It is clear that an early Christian evangelist could preach the triumph of Jesus, his entry into God’s eschatological presence, without mentioning the alleged emptiness of Jesus’ grave.[31]

In this section we shall put two questions to this early kerygma. First, we must ask whether the Pauline kerygma, insofar as it is cast as a sequence of events, intends to provide an “Easter chronology” of historical happenings running from Good Friday through Easter Sunday and beyond. That is, our first question is whether Paul’s kerygma necessarily commits believers to some chronological progression like the following:

Second, given the emphasis that the formula puts on the appearances to Simon and the other disciples, we shall ask what this text can tell

112

us about the way or ways in which Jesus allegedly appeared to his followers after he died. Specifically, we shall ask whether Paul’s kerygma in First Corinthians is committed to physical, visible manifestations of the risen Jesus.

AN EASTER CHRONOLOGY?

The kerygmatic formula recorded in First Corinthians almost gives the impression of an inchoate Easter chronology, a mythical sequence of events in which first Jesus died and was buried, then he was raised from the dead, and afterward he appeared to Simon and the other disciples. But such is not the case. Consider the following points:

First: Paul’s formula makes no statement about either the time or the place of Jesus’ being raised. As regards the “time” of the resurrection, the phrase “on the third day” is not a chronological designation but an apocalyptic symbol for God’s eschatological saving act, which strictly speaking has no date in history. Thus the “third day” does not refer to Sunday, April 9, 30 C.E., or to any other moment in time.[32] And as regards the “place” where the resurrection occurred, the formula in First Corinthians does not assert that Jesus was raised from the tomb, as if the raising were a physical and therefore temporal resuscitation. Without being committed to any preternatural physics of resurrection, the phrase “he was raised on the third day” simply expresses the belief that Jesus was rescued from the fate of utter absence from God (death) and was admitted to the saving presence of God (the eschatological future). The raising of Jesus has nothing to do with a spatio-temporal resuscitation, a coming-back-to-life in Jerusalem on Easter Sunday morning. “Resurrection” is an apocalyptic term for “being definitively saved by God.”[33]

Second: If, in keeping with the above interpretation, the raising of Jesus is conceived of as a divine act of supernatural, eschatological salvation that took place outside space and time, then no one, whether a believer or not, can have natural, historical access to it as if it were an event that took place one day in the past. We have historical access not to such a supposed event but only to certain faith-claims, made first of all by Simon and then by other of the disciples, that God saved Jesus

113

from the dead. What is more, neither Simon nor any other of the original believers had any natural, historical access to the raising of Jesus. In fact, no scriptural text describes the resurrection and no one claims to have witnessed it. Simon, the original believer, came to hold that the kingdom which Jesus had preached was soon to be fulfilled–indeed, that Jesus was now living in God’s future–on the grounds of an experience that Simon interpreted as an eschatological revelation. The experience and Simon’s first interpretation of it constitute his “Easter experience.” But that interpretation does not, and on its own terms could not, commit Simon to a date in time when an alleged raising of Jesus–a nonhistorical, eschatological act of salvation by God–would have taken place. As we suggested earlier, this “raising” was not an event at all but a secondary apocalyptic interpretation of what Simon had experienced about Jesus.

Third, therefore: In searching out the origins of Christianity, the furthest back we can go in history is not the “resurrection of Jesus,” not even the alleged appearance of Jesus to Simon, but only Simon’s interpretative claim to have received a revelation that the words and works of Jesus were definitively vindicated by God. Earlier than Simon’s “Easter experience” the only relevant event to which we have historical access is the death and burial of Jesus.[34] The text in First Corinthians gives us no warrant to postulate a historical event called “resurrection” which occurred between Jesus’ death and Simon’s experience, and the text gives us no grounds for saying that Jesus’ alleged resurrection took place chronologically before his alleged appearance to Simon.

The terms “resurrection” and “appearances” do not indicate temporal happenings at all. They express faith-interpretations rather than historical events, and they point to apocalyptic eschatology rather than to natural history. Moreover, these two apocalyptic interpretations can be neither separated one from the other nor dated relative to each other. Paul and the other believers of his time could not credibly assert that Jesus had been taken up into God’s future without also claiming that Jesus had been made manifest from there (how else would they have known that Jesus had been raised?). Nor could they claim that Jesus had appeared from the eschatological future without likewise asserting that he had been assumed into it (otherwise they could not

114

claim that Jesus had been revealed as risen). But this interconnectedness of resurrection and appearance does not entail a temporal sequence (“first he was raised, then he appeared”) or even a causal one (“because he was raised he therefore appeared”).

Thus Paul’s text says nothing about earthly activities of Jesus after his crucifixion and gives us no grounds for constructing an Easter chronology in which the resurrection would be a historical event that happened before yet another historical event called the appearance to Simon. Indeed, if both the resurrection and the appearance of Jesus are only derived apocalyptic interpretations of what Simon “saw” in Galilee and what other believers “saw” after him, then as regards the origins of Christianity the only relevant historical event following Jesus’s death was Simon’s experience. If Paul’s kerygma points us backward at all to any “Easter events” in the historical past, it leads us not to a resurrection in Jerusalem one Sunday morning, not even to subsequent appearances of Jesus to Simon and others, but only to the disciples’ interpretative claims that they experienced the triumphant Jesus. The text points us to hermeneutics rather than to history.

Even though Paul’s text is, in fact, innocent of a mythical “Easter chronology” of the risen Jesus, it nonetheless seems to record the church’s first halting step in that misguided direction. As we shall see in the next chapter, the codified interpretation “Jesus was raised on the third day” would eventually be taken as a datable, historical event that took place once at a specific point in time at Jesus’ tomb in Jerusalem. And the formula “Jesus appeared to Cephas” would quickly develop into the elaborate gospel stories of Jesus’ postresurrection apparitions throughout Palestine.

HOW DID JESUS APPEAR?

According to Paul’s list, Simon was the first person to experience an eschatological manifestation of Jesus; and in asking now about the way or ways in which Jesus showed himself after he died, we shall focus entirely on that appearance to Simon. (When I speak about “appearances” in what follows, I am of course referring to alleged appearances–experiences that Simon and the others claimed to have had–with

115

out passing judgment on whether or how those “appearances” actually happened.)[35]

In mentioning Jesus’ appearances to Simon and the others, Paul in I Corinthians does not relate how or where these manifestations took place. To be sure, elaborate narratives about such appearances would eventually make their literary debut in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke (ca. 85 C.E.), but that would not be until some thirty years after Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians and at least fifty years after the events these stories purport to recount. By contrast, in this earliest mention of Jesus’ appearances, written around 55 C.E., Paul does not provide narratives of such appearances but only bare formulaic statements stripped down to a personal subject (Jesus), a descriptive verb (“appeared”), and a personal object or dative (the people who had the experience).[36]

The verb “he appeared” is the most important element in the formula. Paul uses the Greek word ôphthê which is the third person singular, passive voice, of the aorist (past) tense of the irregular verb horaô “I see.” Ôphthê can mean equally that someone “made himself seen,” “showed himself,” or, when used with the dative, as it is here, “was seen by” or “appeared to.” Scholars point out that in the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Jewish Scriptures), ôphthê renders the niph’al (simple passive) of the Hebrew verb ra’ah, “see,” which, when used with le, means “appear.” The Jewish Scriptures frequently use this Hebrew verb and its Greek translation to describe manifestations of God or angels, and the verb always puts emphasis on the divine initiative underlying the appearance rather than on the psychological or physiological processes by which the recipient experienced the manifestation.[37]

In Exodus 6:3, for example, Yahweh says to Moses, “I am the Lord, I appeared [ôphthên]to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob, as God Almighty.” The finite verb here does not describe how God appeared to the patriarchs, whether by means of dreams or physical visions or spiritual insight. In fact, Genesis implies that God first “appeared” to Abraham as a voice: “Now the Lord said to Abram, ‘Go from your country … ‘” (12:1). in short, in these Old Testament contexts the verb horaô and its aorist form ôphthê indicate simply that God actively reveals something that was heretofore hidden. The verb leaves open the

116

question of how (that is, by what physical or psychological processes) the recipients experienced the manifestation.[38]

The same holds true in the text from First Corinthians. In the context of the passage, the verb ôphthê doesnot necessarily indicate the visual sighting of a physical object. For example, Paul lists himself as the last person to receive an appearance of Jesus. He is referring to his experience on the road to Damascus, which, for all its differences from Simon’s experience, is here described with the same verb (ôphthê kamoi, “he appeared also to me,” I Corinthians 15:8). However, in Luke’s three accounts of that scene, Paul hears a voice but sees nothing. In fact he is rendered temporarily blind by “a light from heaven, brighter than the sun” (Acts 26:13; cf 9:3, 22:6). Even more important, when Paul himself described this experience some fifteen years after it happened, he called it not a “vision” but more neutrally an apocalyptic “revelation” (apokalypsis, Galatians 1:12). “He who had set me apart before I was born, and had called me through his grace, was pleased to reveal his son in me [apokalypsai … en emoi]” (1:16).

What is more, the usage here of the verb ôphthê has a particularly eschatological sense to it that forces us to rethink the “temporality” of the appearances. The revelations or appearances to Simon and the others were not understood by them as proofs of a past event (a physical resurrection three days after Jesus’ death). Nor, strictly speaking, did these revelations point to an eternal present in heaven from which Jesus had manifested himself. For Simon, the Jesus in whom he believed had “future” written all over him: The “raising” of Jesus meant that he was already living in the final state of things that was soon to dawn on earth. As far as Simon was concerned, Jesus had appeared from that future, from God’s coming eschatological kingdom; and he was calling them into that future and into the apostolic mission of preaching its imminent arrival. Not to see that eschatological future meant not having seen the risen Jesus at all.[39]

I stress this last point in order to bring out the difference between, on the one hand, Paul’s bare formulaic statement “Jesus appeared to Simon” and, on the other hand, the elaborate and mythological apparition-narratives that emerge in the Gospels of Matthew, Luke, and John some fifty to seventy years later. These later legends, which are the basis of so much Christian art and popular mythology, would almost have

117

the reader believe that at a certain point in time Jesus “came back to life” in a preternatural body that could walk, talk, eat, be touched, and even levitate–with the effect that for six weeks Jesus was able to drop in on his disciples at any time or place (in a graveyard or along a country road or in the middle of a Sunday dinner) and disappear just as quickly.

For Simon, on the contrary, Jesus did not wander through Palestine in a resurrected body for forty days after his death. As far as Simon was concerned, the “appearance” he claimed to have had came from the eschatological future into which Jesus had already been assumed. Simon understood his “Easter experience” as a prolepsis of that future, an anticipation of the kingdom which was soon to arrive in its fullness. That is why neither Simon nor any of the other early believers claimed to see Jesus ascend physically into heaven, and why three of the four gospel writers do not even mention such an ascension [Luke is the exception: 24:50-51; Mark 16:19 is part of the ending added by a later author (16:9-20) and is not part of the original Gospel–ed.]. Such a journey was unnecessary, for the early believers held that God’s rescue (or “raising”) of Jesus from the dead meant that the prophet had thereby been taken into his Father’s eschatological future.

In conclusion: The text from First Corinthians–the first recorded mention of Jesus’ “appearances”–does not tell us how Jesus manifested himself after his death. The verb ôphthê simply expresses the Christian claim that Jesus “was revealed” from the coming eschaton in an entirely unspecified way. The manner in which he was made manifest is not mentioned and is not important. The text does not assert that Jesus appeared in any kind of body (be it natural or preternatural) that the disciples could see or touch, nor does it say that Jesus spoke to the disciples. In fact, since Paul makes no claims here about “visions,” with their physical and ocular connotations, it would be more accurate to speak not of “appearances” of Jesus but more neutrally of eschatological “manifestations” or “revelations.”[40]

To judge from Paul’s early formulation of faith, then, the raising of Jesus from the dead has no chronological date or geographical location ascribed to it and no connection with an empty tomb. In fact, the raising of Jesus seems to be no event at all, but only an expression of what Simon had experienced in Galilee. And as regards the appearance

118

to Simon, the text in First Corinthians, upon closer examination, calls into question the notions (1) that such an appearance was an “event” that occurred after Jesus had physically left his tomb and (2) that Jesus was made manifest to Simon in any visible or tangible way. Jesus’ “appearance” to Simon refers to the eschatological revelation that Simon claimed to have had in Capernaum. It names what we have been calling Simon’s Easter experience.

In other words, when we search for the origins of Christianity, we find not an event that happened to Jesus after he died (“resurrection”), or supernatural actions he allegedly performed (“appearances”), but only apocalyptic interpretations of an experience of Jesus that Simon and others claimed to have had. And the original interpretation underlying these later interpretations seems to have been that God had rescued Jesus from death and appointed him the coming Son of Man. Simon was not theologically equipped to devise an elaborate theology of what had happened to Jesus; rather, he was content to say that God still stood behind what the prophet had preached and would soon send him again. In that sense, the Father had “glorified” Jesus and had let him be “seen” as such.

The text in First Corinthians does not take us very far toward positively interpreting the meaning of Easter, but it does ward off some of the more extreme notions of popular Christianity concerning what happened to Jesus after he died. Now we take the next step. We have seen that Paul’s text incorporates a formula of faith that probably goes back to at least 32-34 C.E., that is, to within two to four years of the crucifixion. But we must tryto burrow even further back than that. We shall continue to probe Simon’s experience, but now we try to capture him in the last few hours before the crucifixion, on the night when Jesus was arrested and when Simon last laid eyes on the prophet.

119

4. The Denial of Jesus

We are trying to return to the very birth of Christianity, to the event that began the enhancement of Jesus’ reputation from eschatological prophet to divine cosmocrator. We have no illusions that we can return to supposed historical events called the “resurrection” or the “appearances” of Jesus. The furthest back we can go in history is Simon’s assertion of his belief that God had vindicated Jesus and that the kingdom was soon to come–an assertion which took the form of various apocalyptic statements, such as “Jesus appeared [from the eschatological future]” and “Jesus was raised from the dead.”

Behind Simon’s assertion of his renewed faith in the kingdom there presumably lay an as yet undetermined experience that could have extended over some period of time and could have been as simple as Simon’s reflection on the life and message of the dead prophet. Whatever the experience was, we have no access to it in an uninterpreted state; we cannot discover the raw psychological processes that Simon went through “before” he understood them in terms of Jesus and the kingdom of God. Such an interpreted experience is unavailable not just to us but to Simon as well, and in fact it is a contradiction in terms.

120

Human experience–that is, history–is not an “objective” succession of happenings in the world. Such happenings, whatever they might be, become history–that is, experience–only when they enter the sphere of human interpretation, which we call “language” in the broad sense (Greek logos). We know only what we interpret, and there is no way out of this predicament, this “hermeneutical circle,” for human beings essentially are the act of making sense (= logos or hermêneia). We cannot peek over the edge of our interpretations to see things or happenings “in the raw,” any more than we can step outside of our logos and see the world as it is without us.

Therefore, our effort to discover the birth of Christianity within Simon’s original Easter experience remains ineluctably caught in a hermeneutical web. As we look back to the origins of Christianity we see not pristine, untouched events but only interpretations: human experiences articulated in human language. Caught as we are within interpretations, our task is, first, to uncover Simon’s primordial interpretation of Jesus both before and after the prophet died, and then to interpret that interpretation. At the birth of Christianity we find–whether as believers or as nonbelievers–not happenings observable in the raw but a hermeneutical task.

What, then, was the original content of Simon’s Easter experience? To answer that question we must enter into the dynamics of Simon’s denial of Jesus on the night of the Last Supper. The matter is of paramount importance, for with Simon’s sin and eventual repentance we come to the innermost secret of the original Easter experience and thus to the birth of Christianity.[41]

The Gospels retrospectively put in Jesus’ mouth a prediction that Simon’s faith would falter when Jesus was arrested–but that he would “turn again” after Jesus had died. Luke, for example, has Jesus say,

Simon, Simon, behold, Satan demanded to have you that he might sift you like wheat, but I have prayed for you that your faith may not fail. And when you have turned again, strengthen your brethren. (Luke 22:31-32)

121

The text does not suggest that Simon’s failure would be an apostasy or loss of faith. Perhaps it was more a loss of nerve, a fall into doubt that severely tested his faith but did not entirely undo it. Simon’s movement from faith to doubt and his turning again to faith begin to reveal to us the content–that is, the primordial interpretation–of Simon’s eschatological Easter experience.

What, then, was Simon’s failure? Was it that, after protesting his loyalty so loudly at the Last Supper, he abandoned Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane when the guards from the Sanhedrin came to arrest him? No, the flight from the garden had certainly been the wisest course, for how could a handful of perhaps tipsy and certainly sleepy men have fended off a band of armed soldiers? All things considered, the wisest course was not to mount a futile show of strength but to flee and save oneself for the future.

Or did Simon’s failure lie in the fact that later that night, when he was questioned in the high priest’s courtyard, he denied that he knew Jesus? No, that too was a prudent decision. The bystanders in the courtyard had no right to know who Simon was or whom he was with. Had they known, they might have seized him too, perhaps even had him crucified. No doubt Simon felt degraded by the incident, but it would be wrong to blame him for what was, after all, an expedient subterfuge. He might be faulted, perhaps, for not organizing a guerrilla band to storm the Sanhedrin and rescue Jesus (even though that would have been entirely contrary to the prophet’s wishes); but he should not be condemned for saving his life instead of needlessly throwing it away.

The Gospel says that after Simon had denied Jesus in the courtyard,

the Lord turned and looked straight at Simon, and Simon remembered the word of the Lord, “Before the cock crows today, you will deny me three times.” And he went out and wept bitterly. (Luke 22:61-62)

Much has been made of this wordless encounter between the guilty Simon and his captive master. It would seem that with that silent gaze Jesus was confronting Simon with his sin of abandoning Jesus. Is that indeed the case?

122

What was in that gaze of Jesus’? Was it anger at Simon for doing what Simon had to do? Was it sadness that Simon had denied knowing him? It is difficult to imagine that Jesus could have been so foolish and resentful–or that he so badly wanted a fellow martyr–that he would expect Simon to stand up in the courtyard of the Sanhedrin and declare, “I’m with him! Take me too!” If Jesus’ gaze was meant to confront Simon with his sin, that sin could not be the petty lie of denying that he knew Jesus.

Or did Simon’s sin consist in his not being at the foot of Jesus’ cross the next day? Perhaps Simon did feel regret at not assisting at Jesus’ final agony, but what difference would it have made if Simon had been there? His presence might have been a gesture of solidarity, a last act of friendship, perhaps even a chance for the disciple to purge himself of his grief. But as far as the history of salvation goes, it would have been an indifferent act.

Such attempts to identify Simon’s failure by sentimentalizing his sense of guilt–as, for example, Bach does in the Saint Matthew Passion--lead nowhere. Whatever remorse Simon may have felt for those acts, his failure was not that he abandoned Jesus or denied that he knew him. These acts in no way touch on Simon’s real flight and his denial of Jesus. To know how Simon sinned, we must see what he sinned against.

Simon had learned one major lesson from the preaching of Jesus: The apocalyptic line had been crossed, the dead past was over, God’s future had already begun. As we have seen, the name for the crossing of that apocalyptic line was “forgiveness”: the gift of God himself to his people, his arrival among them. Therefore, the entire point of the kingdom was to live God’s future now. But this did not mean looking up ahead toward the future in an effort to glimpse the imminent arrival of God, for he was no longer up ahead in time, any more than he was up above in heaven. He was with his people, in their very midst: “The kingdom of God is among you.” In that sense there was no more waiting, for forgiveness meant that the future–God himself–was becoming present among those who opened a space for him. Crossing the line into the future meant no longer searching for God in the great Beyond, but living the present-future with one simple rule: “Be merciful as your Father is merciful” (Luke 6:36).

123

Simon’s sin, his denial of Jesus, consisted in fleeing from and forgetting what he and all Jesus’ followers had become: the place where the future becomes present. His sin lay not in abandoning Jesus but in abandoning himself. If anything, he did not deny Jesus enough.

Simon’s sin was to have momentarily forgotten where Jesus dwelled, in fact where Simon himself had dwelled. Simon put his hopes on Jesus rather than on what Jesus was about. “Follow me,” the prophet had said, and he meant ” … into God’s present-future.” But Simon was a literalist. As the soldiers dragged his master away, he got up his courage and “followed at a distance” (Luke 22:54). In so doing he began walking back into the past. The Gospel records Jesus as saying: “No one who puts his hand to the plow and then looks back is fit for the kingdom of God” (Luke 9:62). Ironically, Simon was doing just that–looking back toward the dead past–when he followed Jesus from the Garden of Gethsemane through the dark streets of Jerusalem.

Simon’s sin did not lie in abandoning Jesus in Gethsemane or in denying him a few hours later but in following Jesus to the courtyard of the Sanhedrin. His fault was not that he denied Jesus but that he affirmed him too much and feared that if Jesus died, God’s kingdom would come undone. Simon had focused his attention so intensely on Jesus that he ended up taking Jesus for the kingdom and thereby mistaking the kingdom itself. In his desperate effort not to lose Jesus, Simon lost himself and his grip on the presence of God.

Once, when Jesus had told his disciples that his death was inevitable, Simon took him aside and tried to argue him out of it. But Jesus rebuked him: “Get behind me, Satan! You are on the side of men, not the side of God” (Mark 8:33). The point was clear: The only way to save Jesus was to let him die, and then to go on living the kind of life that Jesus had led, a life set entirely on the present-future, on God-with-man. For the rest, “Leave the dead to bury their dead” (Matthew 8:22).

This, I believe, was the real denial: Simon forgot that the kingdom of God-with-man was not any one person, no matter how extraordinary that person might be, that the kingdom could not be incarnated in any hero, not even in Jesus. By following his master to the courtyard of the Sanhedrin, Simon was setting his heart on Jesus rather than on the kingdom. He was turning Jesus into the last thing the prophet

124

wanted to be: a hero and an idol, an obstacle to God-with-man. Simon failed to see that the future had been given unconditionally and could not collapse with the death of one man–because the kingdom was not Jesus but God.

Simon’s threefold “denial” of Jesus in the courtyard of the Sanhedrin was a morally neutral and even a prudent act. The real denial of Jesus lay in holding on to Jesus and thereby forgetting what Jesus was about. Simon erred not in abandoning Jesus but in not abandoning him enough. The right way to acknowledge Jesus would have been to forget him, to let him go, to let him die, without regret. Simon had missed the point: Jesus “was” the kingdom only because he lived his hope so intensely that he became that hope, became the very thing he lived for. And having made his point as well as he could, Jesus had the good sense and courage to die and get out of the way.

After his failure, Simon “turned again.” He did see Jesus again–but only in the sense of remembering, re-seeing, the present-future that Jesus, by living out his hope, had once become. This was not a vision but a re-vision, Simon’s renewal of his former insight into the kingdom. This re-vision was the Easter experience, the rebirth of what Jesus had preached, just as what Jesus preached was a renewal of what had always been the case since the beginning of the world. This re-vision gave Simon his vocation to preach the same message as his master: The sinful past is over; God’s future becomes present wherever men and women live in justice and mercy. While Jesus was alive, he had become what he preached. Now that he was dead, his words were reborn in Simon’s proclamation.

The content of Simon’s eschatological experience was summarized in the simple message that he proclaimed, the same invitation and response that Jesus had preached. The offer was captured in the sentence “The kingdom of God is at hand,” and the demand was even simpler: “Repent” (Mark 1:15). These two parts of the message are reducible to each other, just as all later Christian doctrines are reducible to them. The message that “the kingdom is at hand” meant that God was with his people; but God was with mankind only if they “repented,” that is, changed the way they lived, and enacted the kingdom now.

What Simon experienced-both before and after Jesus’ death-was

125

not a “vision” but an insight into how to live. The question that gave birth to Christian faith was: “Master, where do you dwell?” (John 1:38). Following Jesus did not mean having a vision of the future but rather realizing that God’s future was already present wherever justice and mercy were enacted. Faith was not a matter of possessing the kingdom, but of living the kingdom by enacting one’s hope in charity. The kingdom could not be verified by any kind of “proof” except the proof of how one lived. The proof was all in the doing. In Jesus’ preaching, eschatology had been removed from the mythical context of apocalypse and had become a simple but radical appeal to be as merciful as the Father was. Therefore, for Jesus’ disciples to preach the nearness of the kingdom did not mean to pass on information about an imminent end of the world, but to live an exemplary life “worthy of God, who calls you into his own kingdom” (I Thessalonians 2:12). It meant dissolving eschatology into ethics.

But something else came of Simon’s insight. The core of his re-vision had been that the present-future was still a reality after the crucifixion, that Jesus’ word–the way he lived the kingdom of God-with-man–was true. But the manner in which Simon and the first believers articulated that insight came to be focused not on Jesus’ way of living but on Jesus himself. They announced that his word had been vindicated; and they expressed that vindication by saying that Jesus had been rescued, that is, taken into the eschatological future, and was living there now with God.

This reinterpretation of the kingdom was the first momentous step toward personifying the present-future and turning God-with-mankind into a single individual. In that sense, Simon continued his denial of Jesus by creating Christianity. He reified Jesus’ word, his way of living, into the man himself, and then identified the man with a kingdom that was not present but still to come. Simon gave God back his future by personifying that future as Jesus, who was soon to return. Henceforth, preaching the kingdom of God-with-man meant preaching Jesus as the one to come.

Here the prophet’s original message of God-with-man began edging toward the later Christian doctrine of God-with-one-particular-man. It was not yet a full-blown “ontological christology,” a doctrine of the nature of Jesus as divine (although that would come soon enough). At this point Simon and the others were interested in Jesus only for

126

the role he would play in ushering in God’s eschaton. For the earliest believers the name “Jesus” became a code word for the imminence of that eschaton. This was a portentous shift of focus. Now, alongside the prayer Jesus had taught the disciples–“Father, may thy kingdom come!” (Luke 11:2)–there stood another one: “Maranatha: Come, Lord Jesus!” (cf. I Corinthians 16:22, and Revelation 22:20).

This first step toward founding Christianity was a retreat from Jesus’ original message: It reinserted his trans-apocalyptic preaching into the apocalyptic expectations of the age. There is no doubt that Jesus himself was a child of his times and that his message was clothed in some apocalyptic imagery. But that garment fit loosely and not well. Jesus’ preaching transcended its own language: Its true meaning lay more in the way he lived than in what he said. After Jesus’ death Simon had an opportunity to rescue the core of that message–a unique way of living–from the symbols in which it was couched. But Simon, even more than Jesus, was a child of the age, and ultimately he missed his chance insofar as he interpreted his renewed insight in the apocalyptic terms of a future kingdom, perhaps an “appearance” and even a “resurrection.” He reified the future, sent it up ahead again in time, and identified that future with the Jesus who, he believed, was soon to return. The prophet’s message of urgency and immediacy–“Live the presence of God’s future!”–fell back into an apocalyptical eschatology, the awaiting of a future kingdom. Christianity is built on that mistake.

With Simon’s experience we are present at the turning point: the end of Jesus and the beginning of Christianity. That topic will concern us in a later chapter, but for now we must remain a while longer with the question of the resurrection, the “event” that Christianity proclaims as the basis for the dramatic change in Jesus’ reputation.

There is a text in Saint Mark’s Gospel that seems to overcome the hermeneutical distance that separates us from Jesus’ “resurrection” and that may allow us to discover an uninterpreted “Easter event.” That text, to which we now turn, recounts the story of how Jesus’ tomb was found empty on the Sunday after he died.

127

THE EMPTY TOMB

129

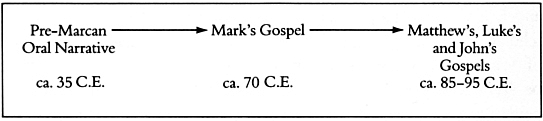

The appearance of Saint Mark’s Gospel, around 70 C.E., brought something radically new into the Scriptures: the first legends about what happened on the Sunday morning after Jesus had died. This event is of paramount importance, for it marks the first literary appearance of what was to develop into the “Easter chronologies” of Jesus’ postresurrection activities.

Mark’s Gospel was the first of the four to be written; the Gospels of Matthew and Luke would follow about fifteen years later (ca. 85 C.E.), and the Gospel of John would be written toward the end of the century. The only Christian Scriptures predating Mark’s Gospel are the epistles of Saint Paul, his ad hoc letters written during the fifties to bolster the faith of his converts. Whereas Paul’s writings hardly mention the life of Jesus except for his crucifixion, Mark’s Gospel presents the putative words and deeds of Jesus from his baptism in the Jordan to his death and burial. Strictly speaking, however, it is not a historical record of Jesus’ ministry but a faith-charged theological treatise that reflects the beliefs and concerns of later Christians, mostly Greek-speaking Jewish converts in the Mediterranean Diaspora.

130

Our concern here is with Mark’s last chapter, his narrative of what happened at Jesus’ tomb on the Sunday after his death. Before this Gospel appeared, scriptural proclamations of Jesus’ resurrection were limited to brief and simple formulaic sentences, such as “God raised him from the dead” (I Thessalonians 1:10). Mark continued the tradition of kerygmatic brevity with regard to the resurrection itself, but he also launched the new biblical genre of narrating stories about what took place immediately after the resurrection.[42] A close look at the final chapter of Mark’s Gospel and at other material in the New Testament may lead us to what actually happened at the tomb on April 9, 30 C.E.

131

1. Easter According to Mark

The Easter story that appears in the last chapter of Mark’s Gospel is brief, bare, and deeply disturbing. Besides failing to mention most of the events that traditional Christian piety associates with the first Easter morning, the gospel story ends without the disciples believing that Jesus had been raised from the dead. It concludes instead with the confusion and disbelief of the women who had gone to visit his grave: “They said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid” (Mark 16:8). Given their reaction, we might find ourselves, as we reach the last word of the Gospel, wondering how faith in the risen Jesus came about at all.

It was precisely this question that moved a later, anonymous Christian writer to flesh out Mark’s concluding chapter (16:1-8, the “first ending”) with eleven more verses (16:9-20, the “second ending”) that bring it into line with the elaborate appearance stories in the later Gospels of Matthew, Luke, and John.[43] However, the original Easter story in Mark–the one we shall focus on in this chapter–is about the confusion and fear that overcame the three women who visited Jesus’ tomb on Sunday morning with the intention of giving him a proper burial. The “first ending” runs as follows:

132

MARK 16:1-8

| I. SATURDAY NIGHT (VERSE 1)

And when the Sabbath was past, Mary Magdalene and Mary the mother of James, and Salome, bought spices, so that they might go and anoint him. II. SUNDAY MORNING (VERSE 2) And very early on the first day of the week they went to the tomb when the sun had risen. III. THE STONE (VERSES 3-4) And they were saying to one another, “Who will roll away the stone for us from the door of the tomb?” And looking up, they saw that the stone was rolled back; for it was very large. IV. THE ANGEL’S TWOFOLD MESSAGE A. The resurrection (verses 5-6) And entering the tomb, they saw a young man [= an angel] sitting on the right side, dressed in a white robe; and they were amazed. And he said to them:

B. A future appearance (verse 7) “But go, tell his disciples and [especially] Peter that he goes before you to Galilee; there you will see him, as he told you.” V. THE REACTION (VERSE 8) And they went out and fled from the tomb; for trembling and astonishment had come upon them. And they said nothing to anyone. For they were afraid. |

There is no more to the earliest recorded account of Easter Sunday morning, and no more to the written Gospel. Mark’s narrative ends there, abruptly. The events at the tomb provoke confusion and fear rather than joy and proclamation, and the women retreat into a hermetic silence. With no report of the birth of Easter faith, Mark’s account seems to leave Christianity stillborn at Jesus’ grave.

Moreover, when we compare Mark’s final chapter with the Easter accounts of the later Gospels and above all with the popular legends about Easter that have grown up over the centuries, the account strikes

133

us as stark and minimalistic. There are no guards at the tomb, no emergence of Jesus from the grave, no burial shroud left behind to prove that the prophet had risen from the dead. Notice what Mark’s Gospel fails to say:

First, Mark’s final chapter does not describe Jesus’ resurrection. As we have already seen, it was well over a century after Jesus’ death before the apocryphal Gospel of Peter (which the Church does not, in fact, accept as authentic Scripture) attempted to describe Jesus’ emergence from the tomb. There is no text in the New Testament that describes the resurrection of Jesus or that claims there were any witnesses to it. For if it indeed was an eschatological event, there would have been quite literally nothing to see. Mark stays within that tradition when he has the angel say simply, “He has been raised.”[44]

Second, Mark’s Easter story is characterized by a stunning absence: The risen Jesus does not appear at all. Indeed, according to this Gospel, once he was sealed in his tomb, Jesus was never seen again. It is true that the angel in the story does allude to a future appearance in Galilee (“there you will see him, as he told you”), but this may well refer to Jesus’ universal appearance at the end of time.[45] In any case, Mark’s Gospel gives no description of such an appearance and has nothing more to say about it. Nor, to be precise, does the angel tell Jesus’ followers to go to Galilee; and judging from the account of the women’s reaction, we get the impression that no one went. In fact, within the rhetorical structure of the narrative, the prediction of the future appearance seems to be tacked on as an afterthought to the centerpiece of the story: the announcement that whereas, yes, Jesus has been raised, he is in fact absent and unavailable to visitors. “He has been raised; he is not here.”

Third, we are struck by the effect that the angel’s message has on the women–or perhaps better, the lack of effect. As far as Mark’s story goes, the women do not believe the angel’s message about the resurrection, and they ignore his order to pass on the word to the disciples. They tell absolutely no one what they have seen and heard (oudeni ouden eipon, verse 8). This passage is the earliest account we have of the events of the first Easter morning; and if it were the only account, we might be left wondering how faith in the resurrection of Jesus originated among his disciples. In any case, Mark is clearly saying that

134

Jesus’ empty tomb is not the origin of that faith, and that if some women did discover such a tomb on Easter Sunday morning, the event led to confusion rather than to faith.[46]

Thus the earliest gospel account of Easter Sunday provides no description of the resurrection, only an announcement that it had happened; no description of a resurrection appearance, but at best only a prediction of one to come; and no indication that the scene at the tomb (if such a scene ever really took place) gave rise to Easter faith.

Nonetheless, for all these apparent defects, the genius of Mark’s story is precisely that it raises more questions than it answers. Mark’s story casts Easter in the interrogative mode, and yet his account may say more about Christian faith than the more mythological accounts that the later Gospels provide. According to the majority of exegetes, all the gospel accounts of the first Easter morning are legends, with or without an original historical base. It is unfortunate, however, that the church has usually preferred to read the later legends, and not this barer and more evocative one, at the annual celebration of Easter.

135

2. An Earlier Legend

Mark’s account of Easter morning occupies a vantage point midway between the elaborate Easter stories that are found in the later Gospels and the even starker oral narrative that exegetes generally agree preceded Mark’s own Gospel. For a moment let us stand at that middle point and look both forward and backward in time.

Looking forward in time from Saint Mark (70 C.E.), we find that the Gospels of Matthew, Luke, and John (written fifteen to thirty years later) make a qualitative leap in the way they treat Easter, in that they offer the first descriptions of Jesus’ postresurrection appearances. Those later Gospels give at least eight accounts of such apparitions, characterized by increasingly concrete physical details of Jesus’ apparitions (ingestion of food, showing of wounds, ascension into heaven, and so forth). But while these legendary additions to Mark are noteworthy, even more

136

important is what the later Gospels omit, namely, Mark’s story about the women’s scandalous disbelief and their frightened flight into silence.[47]

For example, fifteen years after Mark’s Gospel, Luke dropped the women’s disbelief altogether and changed their confused flight from the tomb into a simple “return” to Jerusalem in order to inform the apostles (24:9). Matthew, writing at about the same time as Luke, chose to have it both ways: the women are filled with both fear and “great joy,” and even though they still run from the tomb, it is to tell the disciples what they have seen (28:8). It is as if Mark’s stark account of the women’s fear and incredulity was too troubling for later generations of believers and therefore had to be changed.

Those later revisions of Mark unquestionably resulted in beautiful and moving stories–for example, Saint John’s sublime account of the meeting of Jesus and Mary Magdalene on Easter Sunday morning (20:13-18). But for all their mythological richness, these later Easter stories still leave us wondering about Mark’s startling claim that the first proclamation of the resurrection (by an angel, no less), along with the discovery of the empty tomb, failed to instill faith in the women. Where did Mark’s story come from, and what does it say about the resurrection? To answer those questions we must look backward in time from Mark’s Easter account to the oral story that preceded it.[48]