The Date of the Nativity in Luke (6th ed., 2011)

Richard Carrier

It is beyond reasonable dispute that Luke dates the birth of Jesus to 6 A.D. It is equally indisputable that Matthew dates the birth of Jesus to 6 B.C. (or some year before 4 B.C.). This becomes an irreconcilable contradiction after an examination of all the relevant facts.

The following essay surveys all the evidence both to this effect and against all known attempts to reconcile these authors. It was originally written in 1999 and was revised in 2000 to make it more readable and complete, and to take into account new claims and scholarship; two more revisions of the text were made in 2001, and another in 2006, in conjunction with a much shorter summary being built by the editors of the new Errancy Wiki. Some small additions were then made in 2011 to keep pace with recent publications. Each section of this essay begins with a summary of conclusions in bold type, followed by a sometimes lengthy discussion of the evidence leading to those conclusions. As a result, it is not necessary to read the whole essay if you are looking for quick answers, or only want to read about a particular argument. It is my intention to make this essay absolutely comprehensive. If you are aware of any arguments or evidence bearing on this topic that are not addressed here, please contact me through Secular Web Feedback and I will do the necessary research and expand this essay accordingly.

I. The Basic Problem

Luke

The Date of John the Baptist’s Ministry

Luke’s Description of the Census

Matthew

JosephusII. Was Quirinius Twice Governor?

The Lapis Tiburtinus

The Lapis Venetus

The Antioch Stones

The Date of Quirinius’ Duumvirate in Pisidian Antioch

Vardaman’s Magic “Coin”III. Was There a Census in Judaea Before 6 A.D.?

Did Luke Mean “Before” Quirinius?

Was Apamea a Free City?

How Often Was the Census Held?

Was Quirinius a Special Legate in B.C. Syria?

Was Quirinius Sharing Command with a Previous Governor?

Was “Quirinius” a Mistake for Someone Else?

Can it be a Mere Type-o?

Was it a Census Conducted by Herod the Great?

Was Herod Alive in 2 B.C.?Conclusion

I. The Basic Problem

The Gospel of Luke claims (2.1-2) that Jesus was born during a census that we know from the historian Josephus took place after Herod the Great died, and after his successor, Archelaus, was deposed. But Matthew claims (2.1-3) that Jesus was born when Herod the Great was still alive–possibly two years before he died (2:7-16). Other elements of their stories also contradict each other. Since Josephus precisely dates the census to 6 A.D. and Herod’s death to 4 B.C., and the sequence is indisputable, Luke and Matthew contradict each other.

Luke 2.1-2 says that “It happened in those days that a decree was issued by Caesar Augustus that a census be taken of all that was inhabited. This census first came to pass when Quirinius was governing Syria.”[1.1] During this census, which we know occurred in 6 A.D. (see below), Jesus is born (2.3-7). Then, eight days later, he is circumcised (2:21), and after the 40th day (2:22; cf. Leviticus 12:2-4) he is publicly presented at the temple in Jerusalem (2.21-38), where two different people publicly proclaim him the messiah (Simon and Anna: 2:25-38), one of whom even continues telling everyone about him in the temple afterward. Then his family returns to Galilee (2.39-40), where Jesus grows up, and his family returns to Jerusalem every year thereafter (2.41) for twelve straight years (2:42).

It is often claimed that Luke has John the Baptist and Jesus born around the same time, but, first, this is not necessarily true and, second, this still would not entail a corroboration of Matthew. The second point is more forceful than the first: namely, that Luke is referring to Herod Archelaus, not Herod the Great, and I think this most likely (see 1.1.3 below).

Though I think Luke is certainly only referring to Archelaus, the other possibility deserves further discussion. Three months before John is born, Gabriel announces to Mary only that she will conceive (1:31, 36), not that she already has. In fact, Luke never says when Mary conceives. Instead, John appears to have already passed most of his childhood by the time Jesus is born (1:80). Given Jewish law at the time (Mishnah, Abot 5.21), which held that a man becomes subject to religious duties on his thirteenth birthday (which would be John’s “day of public appearance to Israel”; we see that day for Jesus in 2:42ff.) and other parallels between Jesus and John (cf. 1:80 and 2:40), it would be reasonable to assume that Luke has in mind that John was nearly twelve when Jesus was born (since “in those days” from vv. 2:1 picks up the “day” of the previous vv. 1:80).[1.1.2] This would easily rescue Luke from charges of chronological error, since he reports that John’s birth was foretold in a vision “in the days of Herod king of Judaea” (1.5), and if John was born around then, it would be an error to have Jesus born around the same time if Herod the Great were meant, since he was long dead by the time the census occurs. Of course, this is moot, since this Herod the King may well be Herod Archelaus, not Herod the Great, so if Luke did mean John was born only six months before Jesus, then Luke clearly meant Archelaus, who in that case would have been deposed between the two births, explaining why the census suddenly became an issue exactly then.[1.1.3] Still, we are not told how much time intervened between the annunciation and John’s birth (1.22-24), but if we interpret Luke as describing a twelve-year interval, it is notable that he places the birth of John in exactly the same year that Matthew seems to place the birth of Jesus (6 B.C.).

There are two peripheral matters regarding Luke that require brief digression for those who are concerned about them. The first is the date of John the Baptist’s ministry, and the second consists of the alleged “errors” of Luke in his description of the census. Each will be addressed here in a separate box, which can be skipped if desired since they aren’t essential to the issue of when Jesus was born.

|

|

The Date of John the Baptist’s Ministry

| |

The Date of John the Baptist’s Ministry

|

|

|

Luke’s Description of the Census

| |

Luke’s Description of the Census

|

The above two defenses of Luke do not mean that Luke is correct. I think using a census in the story to explain both of Jesus’ reputed ancestral homes (the village of Nazareth and the town the messiah had to come from, Bethlehem) is rather convenient and looks more clever than genuine. And Luke’s probable use of Josephus suggests a deliberate attempt to paint a veneer of genuine history around an otherwise questionable hagiography. For Luke’s accuracy is only provable in details such as these, which were already painstakingly researched by other men and published in Luke’s own day. When we get to the question of whether Jesus was actually born during this census or any other, or even to the question of how Luke could possibly know this (and Matthew apparently not know it), we are talking about an entirely different problem. Nevertheless, though Matthew’s account looks and smells like a fantastical legend (see below), I do not see Luke’s account as historically impossible, as some have tried to argue. To the contrary, I think Luke strained to force his story to seem more plausible than it already was when it got to him. But if one of the two authors must be correct, then Matthew is far more likely the one who has it wrong.

Matthew 2.1 begins by reporting that “after Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judaea in days of Herod the king” [2.1] the magi reported to Herod that a King of the Jews had been born, stirring Herod and “all Jerusalem” to be troubled (2.3). Herod then seeks to kill the baby by killing all the children in Bethlehem and surrounding areas who would have been born around the right time, i.e. two years earlier (cf. 2.7, 2.16). This would constitute the murder of 10% of the population of that territory [2.2], possibly several hundred children. This is an unimaginable atrocity which probably never happened. A clear and reprehensible crime, it would have almost certainly started a war, and at least been mentioned among the many evil deeds of Herod catalogued by Josephus. Moreover, the myth of the evil tyrant trying to keep his reign by seeking to kill one or more babies (often as a result of an oracle of an usurper’s birth), but being thwarted somehow, was a common legendary motif in the period, from Oedipus and Cypselos of Corinth, to Krishna, Moses, Sargon, Cyrus, even Romulus and Remus, just to name the most famous examples. The author of Matthew also gives us some internal evidence that this is mythical: for if so public an event had really occurred (2:3, 2:4, 2:16), it is curious that no one remembers it later (13:54-56), not even Herod’s own son and heir (14:1-2). And Matthew is more prone than any other New Testament author to contrive the fantastical–his account of the crucifixion strains credulity, with its rock-splitting earthquakes and hordes of undead descending on the city (27:51-3), and his account of the empty tomb is as fabulous as legends can get (28:2-5).[2.3] Nevertheless, if we believe Matthew at least has the date right, if not the real events, he is placing the birth of Jesus around 6 B.C., since Jesus was supposedly about two years old when Herod was still alive, and though we do not know how much time passed between this supposed “mass murder” and Herod’s death, the narrative implies that it was not long. We might also imagine Herod to have been playing it safe, and thus the date might be 5 or even (though rather unlikely) 4 B.C., or some time could have passed before his death, and thus the date implied could be many years before 6, though the coincidence of Luke’s effectively dating the birth of John to 6 B.C. may hint at a possible source of confusion (if there is any true story at all being preserved in these accounts, which is not very likely).

This discrepancy is not the only one. Matthew contradicts Luke (above) on other points of detail. Luke describes Jesus being presented in the temple to repeated public pronouncements of his status, which would not have escaped Herod’s supposedly murderous eye (or memory). Matthew, in contrast, has Herod only finding out roughly two years later, from foreigners. The family of Jesus, according to Matthew, flees to Egypt and stays there until Herod’s death (2.15, 2.21-23). In fact they stayed away from Jerusalem, not only for as many as two intervening years or more, but for the entire ten-year reign of Herod’s successor Archelaus (2.22) as well. This flatly contradicts Luke’s claim that they stayed in Nazareth the whole time, from the very beginning, and went to Jerusalem every year without fail. The two accounts thus contradict each other in the most fundamental way: if Matthew is right, Luke’s account fails to make any plausible sense at all, and vice versa. For the one story entails that Jerusalem was dangerous for the child Jesus, while the other entails that it could not have been. One story has the family start in Nazareth, then journey to Bethlehem and back again, while the other story has the family start in Bethlehem, then flee to Egypt, then find a new home in Nazareth only to avoid the wrath of Archelaus. Other details could be reconciled, but it is strange the authors themselves did not do this. For example, one mentions a visit by magi but not shepherds, the other shepherds but not magi. But these can be reconciled only by supposing that each author by some queer chance failed to mention the other’s similar detail, though one wonders how they could know so much and so little at the same time. But the other details are inescapably at odds. They are telling different stories.

Josephus writes that when Archelaus, the successor of Herod the Great, was exiled:

Archelaus’s country was assigned to Syria for purposes of paying tribute, and Quirinius, a man of highest rank, was sent by Caesar to take a census of things in Syria and to make an account of Archelaus’s estate. [3.1]

And:

Quirinius was a man of the Senate, who had held other offices, and after going through them all achieved the highest rank. He had a great reputation for other reasons, too. He arrived in Syria with some others, for he was sent by Caesar as a governor, and to be an assessor of their worth. Coponius, who held the rank of knight, was sent along with him to take total command over the Jews. And Quirinius also went to Judaea, since it became part of Syria, to take a census of their worth and to make an account of the possessions of Archelaus. [3.2]

The primary function of a census in antiquity was to assess not merely property, but the total manpower for the purpose of direct taxation, and that is why it was routine to conduct a census upon assuming control of a province, and obviously why Josephus describes it in just such terms. What is clear here is that Quirinius did not take control of Judaea until after the removal of Archelaus, and Archelaus followed Herod the Great (even Matthew 2.22 confirms this). This entails that some years necessarily had to follow between the death of Herod the Great and the arrival of Quirinius, so on this evidence there is a clear contradiction between the Gospels: Luke places the birth after the death of Herod, Matthew before.

How great is the discrepancy? Josephus writes:

In the tenth year of Archelaus’s government the leading men in Judaea and Samaria could not endure his cruelty and tyranny and accused him before Caesar…and when Caesar heard this, he went into a rage…and sent Archelaus into exile…to Vienna, and took away his property.[3.3]

So roughly ten years separate the death of Herod and the arrival of Quirinius. When was the census held in Judaea? Josephus says quite unequivocally that:

Quirinius made an account of Archelaus’ property and finished conducting the census, which happened in the thirty-seventh year after Caesar’s defeat of Antony at Actium. [3.4]

The victory at Actium is universally agreed to have happened in 31 B.C. The evidence for this is truly insurmountable, confirmed in countless histories, and inscriptions, papyri and other physical evidence. So the census occurred in 6 A.D., which is the 37th year (beginning with 31 B.C., since the ancients reckoned inclusively). This is independently confirmed by Cassius Dio and corroborated by Roman coins.[3.5] It also fits what we know about Quirinius from an inscription (the Lapis Venetus). It is also notable that Josephus attributes the rebellion of Judas the Galilean to this census,[3.6] a detail which Acts 5:37 confirms.[3.7] This then puts the death of Herod at 4 B.C. reckoning from the ten years of the reign of Archelaus, and fittingly, in his account of Herod’s reign, Josephus places his death in that very year. But even if we could fudge the year of Herod’s death,[3.8] we cannot escape the fact that some years must separate his death and the census, since we have to account for the reign of Archelaus in between, so a historical contradiction between Matthew and Luke persists.

II. Was Quirinius Twice Governor?

Some have tried to reconcile Matthew and Luke by inventing a second governorship of Quirinius, placing it in the reign of Herod the Great. However, we have no evidence at all that Quirinius served as governor of Syria twice, much less that he did so when Herod was king of Judaea. Moreover, no one ever governed the same province twice in the whole of Roman history, making the very proposal implausible. Three inscriptions and a coin have been used to imply otherwise, but none of these items contain any of the information claimed by those who want Quirinius to have been twice governor, and they offer no support to the theory. We also know who was governing Syria between 12 and 3 B.C. and therefore Quirinius could not have been governor then (or before, since he was not qualified before the year 12). Also, in section 3 it will be shown that there was never any such thing as a dual governorship, nor could there have been, given the nature of Roman political and social organization, and even if Quirinius had been governor or co-governor of Syria at an earlier date, no census could have been conducted in Judaea while Herod or his successor Archelaus were alive.

Some Christian apologists, following extremely outdated scholarship, have tried to argue (or have even stated as if it were a fact) that Quirinius was actually governor of Syria on two different occasions–the first time, conveniently, while Herod was alive. Therefore, this argument goes, the census Luke is talking about happened in the days of Herod the Great. Unfortunately, this fails to solve the other contradictions between Luke’s and Matthew’s accounts. It is also both groundless and implausible. Nevertheless, every single piece of evidence we have about Quirinius has been twisted into “evidence” of a second or earlier governorship of Syria, and evidence has even been invented wholesale–once by an innocent mistake, and once by pseudoscientific insanity. This “evidence” consists of three inscriptions and one coin, which I will examine in detail.

But first I will mention the several preliminary reasons why this “theory” is absurd. First, we know that Quintilius Varus, not Sulpicius Quirinius, was governor of Syria from 7 B.C. to just after Herod’s death in 4 B.C. (and Calpurnius Piso came after him), while before him Sentius Saturninus held the post from 10 B.C. to 7 B.C., and he took the post immediately after Marcus Titius, who probably had been appointed in 13 B.C. (as three years was the typical length of a governorship).[4.1] In other words:

| 13-10 B.C. | Marcus Titius |

| 10-7 B.C. | Sentius Saturninus |

| 7-4 B.C. | Quintilius Varus |

| 4-1 B.C. | Calpurnius Piso |

There is no room here in which to fit Quirinius. And since we know he first attained the consulship in 12 B.C.,[4.1.5] and only ex-consuls held the governorship of Syria in the time of Augustus, he could not have governed before that year. This means one would have to propose that Jesus was born between 12 and 10 B.C. even for this theory to be remotely possible, but that still would be ad hoc, involving a truly maverick position regarding the chronology of Jesus, presuming an unusually short tenure for Titius, inventing a spot for Quirinius nowhere attested, and still not solving the problem of the census (below). Second, we do not even have any evidence that anyone ever served as governor of the same consular province twice in the whole of Roman history, so it would have been extremely unusual and quite remarkable–so much so that it would be odd that no one mentions it, not even Josephus, or Tacitus who gives us the obituary of Quirinius in Annals 3.48, a prime place to mention such a peculiar accomplishment. It is certainly unheard of.[4.2] Now for the reputed evidence to the contrary.

Some have tried to appeal to a headless (and thus nameless) inscription as proving that Quirinius held the governorship of Syria twice, but the inscription neither says that, nor can it belong to Quirinius. The inscription in question is a fragment of a funeral stone discovered in Tivoli (near Rome) in 1764, and is now displayed (complete with an inventive reconstruction of the missing parts) in the Vatican Museum.[5.1] We know only that it was set up after the death of Augustus in 14 A.D., since it refers to him as “divine.” The actual content of the inscription is as follows:

… … … … … … … … …

…KING BROUGHT INTO THE POWER OF…

AUGUSTUS AND THE ROMAN PEOPLE AND SENATE…

FOR THIS HONORED WITH TWO VICTORY CELEBRATIONS…

FOR THE SAME THING THE TRIUMPHAL DECORATION…

OBTAINED THE PROCONSULATE OF THE PROVINCE OF ASIA…

AGAIN OF THE DEIFIED AUGUSTUS SYRIA AND PH[OENICIA]…

… … … … … … … … …

The most obvious problem with this piece of “evidence” is that it doesn’t even mention Quirinius! No one knows who this is. Numerous possible candidates have been proposed and debated, but the notion that it could be Quirinius was only supported by the wishful thinking of a few 18th and 19th century scholars (esp. Sanclemente, Mommsen, and Ramsay). But it is unlikely to be his. We know of no second defeat of a king in the career of Quirinius, though Tacitus writes his obituary in Annals 3.48, where surely such a double honor would have been mentioned, especially since a “victory celebration” was a big deal–involving several festal days of public thanksgiving at the command of the emperor. We also have no evidence that Quirinius governed Asia. Though that isn’t improbable, we do know of another man, Lucius Calpurnius Piso, who did govern Asia and who defeated the kings of Thrace twice, and received at least one “victory celebration” for doing so, as well as the Triumphal Decoration, and who may also have governed Syria.[5.2] Though it cannot be proved that this is Piso’s epitaph, it is clear that it would sooner belong to him than Quirinius. Thus, to ignore him and choose Quirinius would go against probability. Yet even if we lacked such a candidate as Piso, to declare this an epitaph of Quirinius is still pure speculation.

Even more importantly, this inscription does not really say that the governorship of Syria was held twice, only that a second legateship was held, and that the second post happened to be in Syria.[5.3] From what remains of the stone, it seems fairly obvious that the first post was the proconsulate of Asia. This means that even if this is the career of Quirinius, all it proves is that he was once the governor of Syria.

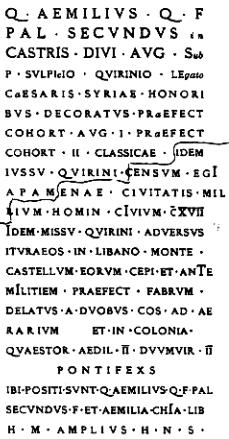

Another inscription, actually mentioning Quirinius, often called the “Aemilius Secundus” (after the name of the man whose epitaph it is), is quite shamelessly abused by numerous people attempting to reconcile Matthew and Luke. The funeral stone of Aemilius Secundus was acquired in Beirut by merchants from Venice sometime before 1674, and it may have been set up there originally.[6.1] It records, among other things, that Secundus was a decorated officer serving under Publius Sulpicius Quirinius when the latter was governor of Syria, some time during the reign of Augustus, and when in this command Secundus helped conduct a census–taking care of assessing a Syrian city (Apamea)–and took out a bandit fortress in the Lebanese mountains. This confirms only that Quirinius was governor of and conducted a census in Syria. That really does no more than confirm that Quirinius conducted a census in 6 A.D. as governor of Syria. But since no date is given, nor any datable details at all, apologists have tried to invent dates that suit them, and then claimed this epitaph as a bogus source of “confirmation.” The inscription, found broken in two but reassembled, reads as follows (small letters in the sketch represent missing or damaged letters):

| QUINTUS AEMILIUS (SON OF QUINTUS) SECUNDUS OF THE PALATINE TRIBE, IN THE SERVICE OF THE DIVINE AUGUSTUS, UNDER PUBLIUS SULPICIUS QUIRINIUS THE LEGATE OF CAESAR IN SYRIA, WAS DECORATED WITH [THESE] HONORS: PREFECT OF A COHORT FROM THE FIRST AUGUST LEGION; PREFECT OF THE SECOND FLEET; ALSO CONDUCTED A CENSUS BY ORDER OF QUIRINIUS IN THE APAMENE COMMUNITY OF 117,000 CITIZENS; ALSO, WHEN HE WAS SENT BY QUIRINIUS AGAINST THE ITURAEANS ON MOUNT LEBANON HE CAPTURED THEIR CITADEL; AND BEFORE HE WAS IN THE ARMY AS OFFICER IN CHARGE OF WORKS, HE WAS DELEGATED BY THE TWO CONSULS TO RUN THE TREASURY; AND WHEN HE WAS LIVING IN A COLONY HE SERVED AS QUAESTOR, AEDILE TWICE, DUUMVIR TWICE, AND PONTIFEX. QUINTUS AEMILIUS SECUNDUS, SON OF QUINTUS, OF THE PALATINE TRIBE, HAVING PASSED ON, AND AEMILIA CHIA, [HIS] FREEDWOMAN, HAVE BEEN LAID TO REST HERE. THIS MONUMENT NO LONGER BELONGS TO [HIS] HEIRS. |

As one can see, the inscription does not say and gives no clues when the census occurred. The latest scholar to examine the issue, Fergus Millar, has good reason to think that this was actually the very same census of 6 A.D.,[6.2] and this is the most logical conclusion: Josephus says that Quirinius was conducting a census in Syria at the time Judaea was annexed, and the Apamea that this inscription refers to (see below) was part of the Roman province of Syria. Nevertheless, I will give one typical example of how apologists abuse this evidence, and how the story gets distorted in transmission by careless authors.

David Allen Rivera reports:

Dr. Jerry Vardaman, an archaeologist at the Cobb Institute of Archaeology, at the Mississippi State University, deciphered a stone tablet known as the “Amelius Secundus,” which had been discovered in Beirut, Lebanon, over 300 years ago, and is now at the Venice Museum. Written in 10 BC, Vardaman says it refers to a census ordered by Quirinius, the governor of Syria, which took place before that, and seemed to be the one referred to by Luke.

Rivera’s source for this information is an undated article in the The Patriot-News (Harrisburg, PA) written by John Goodrich and entitled ” ‘Comet Sunday’ to Draw Attention to Heavens.” It does not say where Vardaman argues any of this, but I subsequently traced the claim to its source (see below). Of course, it is called the Aemilius Secundus, not Amelius Secundus, but this error is Rivera’s. Everything else Rivera says is entirely correct, except for the date. We do not in fact know the date of its composition, much less that it was 10 B.C., and this is actually unlikely given all the probabilities surrounding Quirinius examined in this essay. It should also be apparent from an examination of the microletters fiasco (see below) that Vardaman’s scholarship is not to be trusted, yet Rivera repeats his claims as if they were matters of established fact. The moral of the story is that readers should be very wary of “facts” touted in defense of Biblical inerrancy.

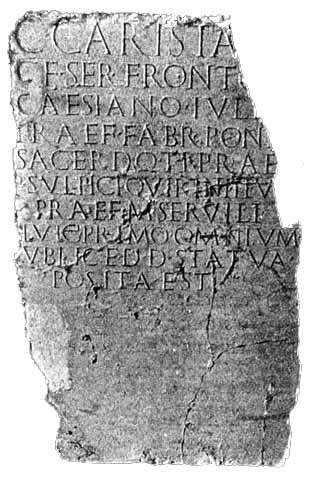

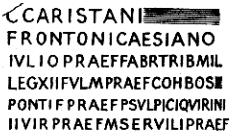

The only other real material evidence mentioning Quirinius to date is a pair of stones found in two different Muslim villages outside Pisidian Antioch in 1912 and 1913. The stones had been removed from wherever they originally lay and then were reused as wallstones. Both are commemorative inscriptions, originally parts of the bases of statues of a certain Gaius Caristanius Sergius (possibly later named Julius Caesianus Fronto, unless these are the names of two different men). Both stones happen to mention as one of his offices the deputy management of a duumvirate held by Quirinius. Once again, the first inscription mentions no date and itself can only be dated by conjecture to sometime between 11 and 1 B.C. The second inscription offers no clues at all, though it was most likely set up after the first, since it mentions additional posts, apparently gained in the interim. Though even earlier dates are remotely possible, later dates are much less likely. Only a sketch exists of one of them, but a photo survives of the other.[7.1] They read as follows:

| GAIUS CARISTA[NIUS…] SON OF GAIUS, SERGIUS FRONTO CAESIANUS JUL[IUS…] OFFICER IN CHARGE OF WORKS, PONTIFEX, PRIEST, PREFECT OF PUBLIUS SULPICIUS QUIRINIUS THE DUUMVIR, PREFECT OF MARCUS SERVILIUS. BY THIS MAN, THE FIRST OF ALL [WITH A] PUBLIC DECREE OF THE DECEMVIRATE COUNCIL, THE STATUE WAS SET UP. |

| BY GAIUS CARISTANIUS … FRONTO CAESIANUS JULIUS, OFFICER IN CHARGE OF WORKS, COMMANDING OFFICER OF THE TWELFTH LIGHTNING LEGION, PREFECT OF THE BOSPORAN COHORT, PONTIFEX, PREFECT OF PUBLIUS SULPICIUS QUIRINIUS THE DUUMVIR, PREFECT OF MARCUS SERVILIUS, PREFECT… |

The only item here that allows any guess at the date the first statue was erected is the fact that it mentions that this was the first man to set up a statue by public decree (in other words, the city legislature voted to pay for it). Since this presumably would not be long after the city was founded (no more than five or ten years), if we can figure out when Pisidian Antioch was established, we will have some idea of when it was set up, though nothing like an exact date. This is not the most famous Antioch (in Syria), founded in 300 B.C. and one of the largest cities in the world at the turn of the era, but “Antioch near Pisidia,” possibly as old but refounded sometime after 25 B.C. under the new name “Colonia Caesareia” (Caesarean Colony), for Roman veterans, definitely in the reign of Augustus, but we actually don’t know for sure when. Only after this date would “decemvirs” be issuing public decrees, since these were the officials comprising the city council under a Roman colonial charter. When all things are considered, we can speculate Quirinius’ duumvirate was held between 6 and 1 B.C. (see box below).

But even with other dates, the inscription offers no proof of a second governorship of Syria. First, there is no particular connection between being governor and being the Duumvir of a city. The one does not entail or even imply the other. Second, this city is well outside of the Roman province of Syria, on the border between Lycia-Pamphylia and Galatia (near modern day Egridir lake in Turkey). Indeed, it is even Northwest of Cilicia, on the other side of the Taurus Mountains. This makes any connection between this office and a governorship of Syria impossible. No one would range so far from his province or have any major connection with a city so thoroughly separated from his area of control.

Even so, this has not stopped some Christians from telling tall tales about what these inscriptions prove. For example, one Christian periodical reports to its readers, as if it were a simple fact:

Luke had stated that Quirinius was the Governor of Syria at the time of Jesus’ birth, however secular records showed that Saturninus was the governor at that time. An inscription was later found in Antioch which showed that Quirinius indeed was governor of Syria at the time.[7.2]

This short statement doesn’t even address the possibility that, if Matthew’s date is correct, either Saturninus or Varus could have been governor at the time (as mentioned above). But what it really gets wrong is the claim that the Antioch inscription proves Quirinius “was governor of Syria at the time.” Every single thing in italics here is false. As we’ve seen, the stones (and there are two, not one) only report that Quirinius was a Duumvir, not a governor, and not in Syria, but well outside that province. And they give hardly any reliable clues as to the date. Only pure speculation can set the date between 9 and 4 B.C., and what little argument could be advanced for a date between 6 and 1 B.C. actually goes to prove that Quirinius was fighting a war in Galatia at the time (see box below) and that refutes the possibility that he was governing Syria (see below), so there is in the end no evidence in these stones regarding any Syrian governorship of any date.

Yet essentially the same claim regarding these stones, with the addition of a false appearance of precision (“Quirinius was indeed governor of Syria in 7 BC as well”), is made by Doug Raymer in his 1999 online essay “The Accuracy of the Bible.” I have traced this particular claim to its source, since it also appears in Kirk R. MacGregor’s online essay “Is the New Testament Historically Accurate?” MacGregor at least tells us where he heard this: he cites page 160 of John Elder’s book Prophets, Idols, and Diggers: Scientific Proof of Bible History (New York: Bobbs Merrill Co., 1960). Elder’s credibility is certainly in question. He reports that the Antioch stone (he, too, only seems aware of one) says that Quirinius was Prefect as well as Duumvir. Obviously, Elder never actually read the stones, for they are about the Prefecture of Caristanius, not Quirinius. He also asserts as if it were a fact that the stone “records his election to the post of honorary duumvir…in recognition of his victory over the Homanadenses” yet I have placed in italics precisely what the stones do not say. Scholars only propose these as possible interpretations, yet Elder seems blithely unaware of the difference. Furthermore, Elder thinks this inscription “proves that Quirinius was in the area as a commander” but he does not seem to understand that it places him well outside the province of Syria, where no governor of that province would have been. Thus, when Elder asserts, again without any qualification, that the date of the inscription “can be fixed as somewhere between 10 and 7 B.C.” we know he is not to be trusted. He claims that the names on the inscription set that date, yet does not explain how. In fact, the names fix no date at all (see box below). It is clear that Elder did not actually read or study the inscription himself–he must be relying on some other scholar, yet he cites no one.

The moral of this story is: always be suspicious of an unsourced “fact” that goes against the common consensus. From an online archive I came across a likely source for Elder’s claims: the hopelessly outdated early 20th century work of G. L. Cheesman.[7.3] Cheesman dates the Duumvirate on the conjunction of two speculations: that the Dummvirate coincided in some way with Quirinius’ war against the Homanadenses–a likely possibility, but hardly a known fact–and that the war happened between 10 and 7 B.C.–a very unlikely possibility in light of more recent archaeological evidence (see box below), but at any rate nothing like a known fact. This teaches us another lesson: in the arguments of Christian apologists, the speculations and inferences of other scholars suddenly and inexplicably become definite facts. For example, on Franke J. Zollman’s online “Dustface Chart” of “Biblical Characters Whose Existence has been Confirmed from Archaeological or Secular Historical Sources” he declares matter-of-factly: “Inscription found in Antioch of Pisidia names Quirinius as legatus.” The position of Legatus (a title that implied, but did not entail, being the governor of a consular province) is nowhere mentioned or implied in the Antioch stones.

Arguing for the date of these inscriptions as between 6 and 2 B.C. is a long and tedious task and is included next only for those who want to explore the issue in depth. Others can skip it.

|

|

The Date of Quirinius’ Duumvirate in Pisidian Antioch

| |

The Date of Quirinius’ Duumvirate in Pisidian Antioch

|

The late Dr. Jerry Vardaman, an archaeologist at the Cobb Institute of Archaeology at Mississippi State University, claimed to have discovered microscopic letters covering ancient coins and inscriptions conveying all sorts of strange data that he then uses matter-of-factly to assert the wildest chronology I have ever heard for Jesus. He claims these “microletters” confirm that Jesus was born in 12 B.C., Pilate actually governed Judaea between 15 and 26 A.D., Jesus was crucified in 21 and Paul was converted on the road to Damascus in 25 A.D. This is certainly the strangest claim I have ever personally encountered in the entire field of ancient Roman history. His evidence is so incredibly bizarre that the only conclusion one can draw after examining it is that he has gone insane. Certainly, his “evidence” is unaccepted by any other scholar to my knowledge. It has never been presented in any peer reviewed venue,[8.1] and was totally unknown to members of the America Numismatic Society until I brought it to their attention, and several experts there concurred with me that it was patently ridiculous.

Nevertheless, his “conclusions” are cited without a single sign of skepticism by Biblical apologist John McRay, who says “Jerry Vardaman has discovered the name of Quirinius on a coin in micrographic letters, placing him as proconsul of Syria and Cilicia from 11 B.C. until after the death of Herod.”[8.2] This actual claim has never been published in any form, but I will address a related published claim by Vardaman, for which some background is necessary. I will devote considerable space to this since, as far as I know, I am the only one who has taken the trouble to debunk this obscure and bizarre claim.

What Vardaman means by “micrographic letters” (he usually calls them “microletters”) are tiny letters so small that they cannot be seen or made without a magnifying glass and could only have been written with some sort of special diamond-tipped inscribers. He finds enormous amounts of this writing on various coins supporting numerous theses of his. Vardaman claims that he and Oxford scholar Nikos Kokkinos discovered microletters on coins in 1984 at the British Museum, but Kokkinos has not published anything on the matter. Nevertheless, Vardaman tells us that some coins “are literally covered with microletters…through the Hellenistic and Roman periods”[8.3] and that “whatever their original purpose(s), the use of microletters was spread over so many civilizations for so many centuries that their presence cannot be denied or ignored.”[8.4] Such fanatical assertions for an extremely radical and controversial theory that only he advocates, and that has not been proven to the satisfaction of anyone else in the academic community, gives the impression of a serious loss of objectivity. Supporting this conclusion is the fact that he cites one authority in support of his thesis that does not in fact support him, yet he does not qualify this citation for his readers but acts as if this makes his theory mainstream.[8.5]

Apart from the fact that it is totally unattested as a practice in any ancient source and none of the relevant tools have been recovered or ever heard of as existing in ancient times, and it has never been subjected to a professional peer review much less accepted by any expert but Vardaman himself, there are several other reasons to regard this as insanity. First, it is extremely rare to find any specimen of ancient coin that is not heavily worn from use and the passage of literally thousands of years, in which time the loss of surface from oxidation is inevitable and significant. Even if such microscopic lettering were added to these coins as Vardaman says, hardly any of it could have survived or remained legible, yet Vardaman has no trouble finding hundreds of perfectly legible words on every coin he examines. Second, to prove his thesis, Vardaman would at the very least be expected to publish enlarged photographs of the reputed microscopic etchings. Yet he has never done this. Instead, all he offers are his own drawings. Both of these facts are extremely suspicious to say the least. Finally, the sorts of things Vardaman finds are profoundly absurd, and rank right up there with Erich von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods.

Here is a typical example:

Notice that this is merely a drawing, not a photograph, and that he gives no indication of scale.[8.6] He never even properly identifies the coin type, and though he quotes the British Museum catalogue regarding it, he gives no catalogue number or citation, so I was originally unable to hunt down a photograph of it or to estimate its size. But even if among the largest of coins it would not be more than an inch in diameter. Most coins were much smaller. Yet his drawing (left) has a diameter of 4.75″ for a scale of at least 5:1 or more, and his blow-up (right) is a little over three-times that, for at least 15:1. That means that his letters, drawn at around a quarter inch in size, represent marks on the original coin smaller than 1/50th an inch, less than half a millimeter.[8.6.5] It would be nearly impossible to have made these marks, much less hundreds of them, and on numerous coins, at minting or afterward (indeed, even the number of men and hours this would require would be vast beyond reckoning), and it would be entirely impossible for them to have survived the wear of time. Yet Vardaman sees them clear as day.

But this is merely the beginning of the madness. Vardaman’s quotation of the coin catalogue establishes this as minted by the city of Damascus in the reign of Tiberius, and the coin itself says “LHKT DAMASKWN” or “328th [year] of the Damascenes,” referring to its re-establishment as a Greek city by the first Seleucus, in the last years of the 4th century B.C. However, coins minted in Eastern Greek cities did not use Latin letters or words, they used Greek–one can see even from his drawing that the real letters on this coin are Greek, spelling Greek words–yet almost all of Vardaman’s “microletters” for some strange reason appear in Latin. Second, and most humorously, all the Latin letters for “J” appear, as Vardaman reproduces them, as modern J’s, yet that letter was not even invented until the Middle Ages! If his J’s were genuine, they should be the letter I. This alone makes it clear his claims are bogus.

But in case there is any doubt: Vardaman claims to find in these tiny letters the clear statement that the coin was minted in the first year of king Aretas IV in 16 A.D. But Damascus was not a part of the kingdom of Aretas then. In fact, he could not have even occupied Damascus (and then only briefly, if at all) until around the death of Tiberius in 36-38 A.D., so Vardaman uses the microletters as evidence that refutes the accepted history. Yet it is a plain contradiction for the minters to boldly date this coin according to their independent Seleucid heritage, and then microscopically reverse that fact and date it by the reign of a recent king. Yet Vardaman doesn’t stop there. The microletters tell him all sorts of new facts about the ancient world, like that the full name of the king was Gaius Julius Aretas, and so on. But even more bizarre still:

The most important references on this coin are to “Jesus of Nazareth.” He is mentioned frequently, often in titles and phrases found in the New Testament, for example, “Jesus, King of the Jews,” “King,” “the Righteous One,” and “Messiah.” Reference to the first year of his “reign” is repeated often…for example, “Year one of Jesus of Nazareth in Galilee [sic].” [8.7]

The absurdity of all this, officially and microscopically inscribed on every coin by the royal mint of the King of the Nabataeans in 16 A.D., stands without need of comment.

Vardaman also “sees” microscopic letters on inscriptions, even though stone, by its roughness and its exposure to weathering, would be even less likely to preserve such markings, even if they had ever been made. Indeed, stones of the day were not polished, making it literally impossible for microscopic letters to be inscribed on them in any visible way. Yet he finds these tiny letters on the very Lapis Venetus inscription (above) showing “that the text dates to 10 B.C., that the fortress Secundus took on Mount Lebanon was Baitokiki, and that the colony mentioned was Beirut.”[8.8] All but the last point would be a valuable addition to our historical knowledge, yet he has never published any papers on these claims. More bizarre still, despite several pages of confused text in his later work on how he arrives at this date, he never even says how he gets the date from the microletters. He merely asserts it over and over again,[8.9] and then appends an unnumbered page with some rough remarks about how his microletters date every office of Secundus by the years from the founding of the Beirut colony in 15 B.C. One could write volumes on the weirdness he finds in his microletters (like the name of the Jewish rebel Theudas on the Lapis Venetus, calling him the king of the Scythians![8.95]). But I think it is clear enough that this is all nonsense on stilts.

Now for the punch line. There is no Quirinius coin. McRay’s reference is to an unpublished paper that no doubt comes up with more complete nonsense about Quirinius in the reading of random scratches on some coin or other, twisted into letters by what must be a chronic mental illness. But Vardaman hasn’t even published this claim. Instead, almost a decade later, when he did present a lecture on the matter, his paper on the date of Quirinius, though over 20 pages in length, never mentions this coin that apparently McRay was told about. Instead, a date of 12 B.C. is arrived at using nonexistent microletters on an inscription. So we can dismiss this claim of Vardaman’s and McRay’s without hesitation.

III. Was There a Roman Census in Judaea Before Quirinius?

Even if Quirinius had been governor a previous time, conveniently during the reign of Herod the Great, and conducted a census, that census could not have included Judaea, for Judaea was not under direct Roman control at that time, and not being directly taxed. There is no example of, or rationale for, a census of an independent kingdom ever being conducted in Roman history. Therefore, the census Luke describes could only have been taken after the death of Herod, when Judaea was annexed to the Roman province of Syria, just as Josephus describes. All attempts to argue otherwise have no merit: Luke did not mean a census before Quirinius, could not have imagined Quirinius holding some other position besides governor, and could not have mistook him for someone else.

Whether conducted by Quirinius or anyone else, there could not have been a census in Judaea before 6 A.D., since the province had not entered direct Roman control before then. But since Quirinius is the first Roman governor to take control of Judaea, we expect a census to occur at that time. This was the nature of Roman imperialism. The whole point of a client kingdom, as Judaea was in the time of Herod the Great and Archelaus, was that the kingdom retain its independence while paying a set and agreed annual tribute. Rome held many rights by treaty, such as the ability to confirm or veto kings, but formal interference ended there. Many territories received this special status for cooperating with Rome in important wars, or when Rome did not want to trouble itself with running the province directly, and typically these client states surrounded and protected the borders of the Empire, providing a kind of buffer zone against invasions.[9.1]

To conduct a census in contravention of such an alliance would have been a notable event indeed, mentioned in many other places as the peculiar event it would have been–and that’s even if it didn’t start an outright war, as almost happened when the Romans finally did conduct a census in Judaea in 6 A.D.[9.2] Why, after all, would Rome want a census of a territory it was not taxing directly? Not only was such a thing never done at any time in the history of Rome, it would have served no practical purpose. According to A.N. Sherwin-White, Horst Braunert’s study of the subject “disproves conclusively the notion of a Roman census before the creation of the province” while also demonstrating that a census was “a necessary consequence of the establishment of direct provincial government.”[9.3] And as we saw above, Josephus confirms a census at the beginning of Quirinius’ reign, just when we would expect it.[9.35]

Not only is a census before the annexation of a Judaean province against all probability and sense, it lacks all evidence of any kind. It is a purely groundless and ad hoc conjecture. Nevertheless, some attempts to “create” evidence for it remain and I will address them here.

Did Luke Mean “Before” Quirinius?

Some have tried to argue that the Greek of Luke actually might mean a census “before” the reign of Quirinius rather than the “first” census in his reign. As to this, even Sherwin-White remarks that he has “no space to bother with the more fantastic theories…such as that of W. Heichelheim’s (and others’) suggestion (Roman Syria, 161) that prôtê in Luke iii.2 means proteron, [which] could only be accepted if supported by a parallel in Luke himself.”[10.1] He would no doubt have elaborated if he thought it worthwhile to refute such a “fantastic” conjecture. For in fact this argument is completely disallowed by the rules of Greek grammar. First of all, the basic meaning is clear and unambiguous, so there is no reason even to look for another meaning. The passage says hautê apographê prôtê egeneto hêgemoneuontos tês Syrias Kyrêniou, or with interlinear translation, hautê(this) apographê(census) prôtê[the] (first) egeneto(happened to be) hêgemoneuontos[while] (governing) tês Syrias(Syria) Kyrêniou[was] (Quirinius). The correct word order, in English, is “this happened to be the first census while Quirinius was governing Syria.” This is very straightforward, and all translations render it in such a manner.

It does not matter if Luke meant that he knew of a second census under Quirinius, since we have already shown that if there were one it would have occurred some time after 6 A.D. Nevertheless, the passage implies nothing about a second census under Quirinius. We have no reason to believe Quirinius served as governor again, or long enough to conduct another census, and the Greek does not require such a reading. The use of the genitive absolute (see below) means one can legitimately put a comma between the main clause and the Quirinius clause (since an absolute construction is by definition grammatically independent): thus, this was the first census ever, which just happened to occur when Quirinius was governor. The fact that Luke refers to the census from the start as the outcome of a decree of Augustus clearly supports this reading: this was the first Augustan census in Judaea since the decree. Another observation is made by Klaus Rosen, who compares Luke’s passage with an actual census return from Roman Arabia in 127 A.D. and finds that he gets the order of key features of such a document correct: first the name of the Caesar (Augustus), then the year since the province’s creation (first), and then the name of the provincial governor (Quirinius). Luke even uses the same word as the census return does for “governed” (hêgemoneuein), and the real census return also states this in the genitive absolute exactly as Luke does.[10.2] This would seem an unlikely coincidence, making it reasonable that Luke is dating the census the way he knows censuses are dated. Luke’s passage lacks a lot of other typical features of a census return (e.g. the year of the emperor), but brevity can account for that, and while Rosen assumes Luke’s prôtê refers to a year, since every province begins with a census and extant census returns indicate the year in that way, we needn’t assume that’s what Luke is doing, though he may have his inspiration from it. In Luke’s context, what he intends to convey is that this is the first Augustan census of Judaea (as opposed to later ones) and that this happened under Quirinius.

But even if one wanted to render it differently, the basic rules of Greek ensure that there is simply no way this can mean “before” Quirinius in this construction. What is usually argued is that prôtê can sometimes mean “before,” even though it is actually the superlative of “before” (proteros), just as “most” is the superlative of “more.” Of course, if “before” were really meant, Luke would have used the correct adjective (such as proterê or prin), as Sherwin-White implies, since we have no precedent in Luke for such a use. Instead, Luke uses prin (Luke 2:26, 22:61; Acts 2:20, 7:2, 25:16), so he would surely have used the same idiom here, had that been his intended meaning. But there is a deeper issue involved. The word prôtê can only be rendered as “before” in English when “first” would have the same meaning–in other words, the context must require such a meaning. For in reality the word never really means “before” in Greek. It always means “first,” but sometimes in English (just as in Greek) the words “first” and “before” are interchangeable, when “before” means the same thing as “first.” For example, “in the first books” can mean the same thing as “in the previous books” (Aristotle, Physics 263.a.11; so also Acts 1:1). Likewise, “the earth came first in relation to the sea” can mean the same thing as “the earth came before the sea” (Heraclitus 31).[10.3]

Nevertheless, what is usually offered in support of a “reinterpretation” of the word is the fact that when prôtos can be rendered “before” it is followed by a noun in the genitive (the genitive of comparison), and in this passage the entire clause hêgemoneuontos tês Syrias Kyrêniou is in the genitive. But this does not work grammatically. The word hêgemoneuontos is not a noun, but a present participle (e.g. “jogging,” “saying,” “filing,” hence “ruling”) in the genitive case with a subject (Kyrêniou) also in the genitive. Whenever we see that we know that it is a construction called a “genitive absolute,” and thus it doesn’t make sense to regard it as a genitive connected to the “census” clause. In fact, that is ruled out immediately by the fact that the verb (egeneto) stands between the census clause and the ruling clause–in order for the ruling clause to be in comparison with the census clause, it would have to immediately follow or precede the adjective “first,” but since it doesn’t, and the entire clause is separated from the rest of the sentence, it can only be an absolute construction. A genitive absolute does have many possible renderings, e.g. it can mean “while” or “although” or “after” or “because” or “since,” but none allow the desired reinterpretation here.[10.4]

John 1:15 and 1:30 are a case in point: the context is clearly established by the point of contrast being made, “he who comes after me [opisô mou] is ahead of me [emprosthen mou] because he was before me [prôtê mou].” Again, the meaning is “because he was first [in relation] to me,” especially since the subject is Jesus, who was just described as the first of all creation (1:1-14). So here we have an example of when prôtos means “before,” yet all the grammatical requirements are met for such a meaning, which are not met in Luke 2:2: the genitive here is not a participle with subject, but a lone pronoun (thus in the genitive of comparison); the genitive follows immediately after the adjective; and the earlier prepositions (opisô and emprosthen) establish the required context. Since this is clearly not the same construction as appears in Luke 2:2, it provides no analogy.[10.5] And this is in John. Luke never uses prôtos as “before” in such a chronological sense.

As a genitive absolute, further separated from prôtê by a verb, the Quirinius clause cannot have any grammatical connection with prôtê. It therefore cannot mean “before” in this context. Nor does it make any sense to “retranslate” the phrase as “this census happened to be most important when Quirinius was governing Syria.”[10.6] That requires a context in order for the word “first” to be read as modifying an actual or implied adjective of “importance,” but no such adjective is present or implied. Instead, the narrative clearly intends to explain why Joseph is going to Bethlehem. A digression away from that point would require an explanation, simply to make the digression intelligible. Since Luke gives no such explanation, he cannot have intended this to be a digression, much less one so obscurely worded. Luke can only have meant this to be the reason for Joseph’s journey, and that’s how every ancient reader would have read it. Therefore, “this [Augustan] census first happened [in Judaea] when Quirinius was governing Syria” is the only contextually plausible reading of Luke’s Greek. Any other interpretation convicts Luke of being a talentless and unintelligible author.

Besides making no sense grammatically, neither of these alternatives fits the fact that no census before Quirinius would have affected Joseph or Bethlehem, as shall be demonstrated below. Therefore, Luke cannot have meant “before” (either directly or indirectly) unless he was fabricating the whole story.

Ronald Marchant (in “The Census of Quirinius“) proposed that the “census of an Apamenian state” mentioned in the Lapis Venetus (above) proves that independent states could be subject to a census.[11.1] But Marchant has his facts wrong. The state in question was not free at the time of the census, but Roman. The city is not precisely named, and we know of four cities named Apamea that were under Roman influence before the 2nd century A.D., but none were free after 12 B.C., and only two were large enough to have the numbers of citizens stated in the inscription. Of these two, the more famous Apamea on the Orontes is the only one in Syria, and it lost its freedom before the 20’s B.C. for having sided with Pompey against Caesar (even though it did so under compulsion, having been captured by Pompey in 64 B.C.). The other, Apamea Celaenae (in Asia Minor), lost its freedom sometime in the 2nd century B.C.[11.2] I can only guess that Marchant mistook a reference to “free inhabitants” as a reference to a free state, but such a mistake would betray a profound ignorance of the basic vocabulary of Roman history. Equally so if Marchant thinks that Apamean coins indicate the city was free, for a great many cities subject to Rome were granted the right to mint their own coins. Likewise, Paul Barnett points to a census revolt that was put down by legions in Cappadocia in 36 A.D. (Tacitus, Annals 6.41), but Cappadocia had already been annexed as a Roman province in 17 A.D. (Annals 2.42, 2.56). So this was a tribal revolt against an ordinary Roman census, not a census conducted outside or independently of Rome.

How Often Was the Census Held?

This is not much of an argument really, but it is a claim that really needs correction since it is so frequently stated, betraying the ignorance of those who state it. Kirk R. MacGregor says in Is the New Testament Historically Accurate? that:

Archaeological discoveries show that the Romans had a regular enrollment of taxpayers and also held censuses every 14 years. This procedure was supposedly begun under Augustus and the first took place in either 23-22 B.C. or in 9-8 B.C. The latter would be the one to which Luke refers.

This essentially paraphrases John Elder (above). John McRay has made a similar claim, stating that “the sequence of known dates for the censuses clearly demonstrates that one was taken in the empire every fourteen years.”[12.1] These two men and many other apologists use this claim as part of their argument that a census of Judaea could theoretically have happened in 8 B.C., fourteen years prior to the census in 6 A.D., perhaps in the very governorship of Saturninus as Tertullian allegedly claimed (below), or in the supposed “earlier” governorship of Quirinius.

Of course, everything covered above already makes this irrelevant with respect to Judaea, and thus of no help in reconciling Luke with Matthew, so there really is no need to debunk it. But it is such a glaring error that it must be corrected. First, all these claims take for granted the reality of an “empire-wide registration” (based on what Luke appears to say, cf. box above), but there never was such a thing until the massive enrollment made by Vespasian and Titus in 74 A.D.[12.15] Thus, since censuses were scattered and never uniform, no “cycle” could ever have been a uniform reality. We know of only two provinces which, owing to their peaceful nature and unusually well-organized infrastructure, were regularly assessed: Sicily and Egypt. But their cycles weren’t the same. The constitutional census cycle for counting Roman citizens was actually five years, not fourteen, and this was actually maintained in Sicily in rare conjunction with a regular census of non-citizens in that province. This was only due to the fact that it had been placed under a special tax system by the kings that ruled the island before the Roman conquest, which the Romans simply continued.[12.2] But regular civil war and the unwieldy size of the empire in the 1st century B.C. resulted in this cycle being disrupted elsewhere. Even after the civil wars were ended, Augustus was only able to complete three of the general censuses in his long reign, which were only of Roman citizens, not provincial inhabitants. These were taken in 28 B.C., 8 B.C., and 14 A.D.[12.3] This flatly refutes any possibility of a fourteen year cycle for these censuses. One comes twenty years after another, then twenty two years after that. They were supposed to have been completed every five years, so if Augustus couldn’t even accomplish that, it is wholly implausible that he was more successful among his non-citizen populations.

As far as provincial censuses go, we have our second best information from Gaul. Censuses under Augustus were performed there in 27 B.C., 12 B.C., and 14 A.D. (this last was completed only two years later due to local unrest). None of these fits a fourteen-year cycle. Other provinces also fit no pattern. For instance, we also know that a census was taken in Cyrenaica (North Africa) in 6 B.C.[12.4] Our best information comes from Egypt, since from that province alone we actually have countless papyrus census returns. Egyptian administration was unique, for like that of Sicily, it was simply the system employed by its previous ruler (Queen Cleopatra), which the Romans found convenient to continue. In Egypt there was a fourteen-year cycle, but this was the direct consequence of a particular capitation tax unique to Egypt in which everyone paid an annual tax after reaching the age of fourteen. This tax may have existed in Syria, but alongside a different capitation tax on women that began at age 12 (Ulpian, cf. Justinian’s Digest 50.15.3), which would have entailed a 12-year census cycle, or less, if any. But we are unsure when these taxes began, whether they ever applied to Judaea, or whether Syria was as well-organized as Egypt in the first place. No matter how you look at it, a fourteen-year cycle would not apply to any census in which Quirinius was involved. That a census in 6 A.D. matches the Egyptian cycle could be a coincidence, or the result of a special reorganization of all the Eastern administrations in that year, but this does not entail the cycle was observed in Syria or Judaea either before or after that year.[12.5] It could have been, or any other cycle, or no consistent cycle at all.

Was Quirinius a Special Legate in B.C. Syria?

Another proposal is that hêgemoneuontos tês Syrias might mean simply “holding a command in Syria” and since Quirinius is known to have fought a war in Asia Minor between 6 B.C. and 1 B.C. (see above), perhaps Luke means to refer to the time when Quirinius was fighting this war, and not actually “legate of Syria.” This doesn’t actually solve any of the problems already discussed so far–no census of Judaea could have been held before 6 A.D. But the argument is not even reasonable to begin with. First, it makes no sense to date an event in Judaea by referring to a special command in a war in Asia. Why not simply name the actual legate in Syria? There is no reason to pass over the most obvious man and name another who has absolutely nothing to do with Judaea, much less a census there.

Second, just because Quirinius was probably assigned a Syrian legion to fight bandits on the mountain border between Galatia and Cilicia, it does not follow that he had any kind of command in Syria.[13.1] To the contrary, he was in the province of Galatia, not Syria, and by special command of Augustus. It only makes sense that he was appointed legate of Galatia for this war, for otherwise the actual legate of Galatia would have been fighting it. A Syrian legate would have no business fighting a war in someone else’s province, especially in a territory that would leave him cut off from his own province by a large mountain range: for the Homanadenses were active in the mountain-lake valley in Galatia, boxed in by the mountains of Pisidia, Lycaonia, and Isauria–the valley surrounding Egridir lake, Turkey, on a modern map. Every expert familiar with the facts agrees that “only an army coming from the north could subjugate mountain tribes” in that region, in other words an army led from the province of Galatia, not Syria.[13.2] So it would be quite nonsensical of Luke to refer to Quirinius’ command and probable governorship in the province of Galatia as “holding a command in Syria,” all the more so since “being a ruler of Syria” is what the phrase actually means anyway (since “Syria” appears in the genitive, not dative case).

Was Quirinius Sharing Command with a Previous Governor?

To get around the problem that all the governors of Syria between 12 and 3 B.C. are already known, some have tried to argue that Quirinius was actually holding a dual governorship with one of those other known governors. This is truly a desperate ad hoc argument, for there was never any such thing as a dual governorship under the Roman Empire, and it would be very strange if there were.[14.1] It also does not solve the problem of the census–for even if Luke was referring to an earlier date, there could not have been a census of Judaea then, as shown above. Nevertheless, it is argued that Roman provincial commands were ambiguous and thus could be held by multiple persons at the same time, though this is argued with no evidence whatsoever, and it is flatly contradicted by the evidence we do have.

I have seen only two examples offered as evidence to the contrary, but they do not make the case. The first comes from Josephus, where the casual remark “there was a hearing before Saturninus and Volumnius, who were in charge of Syria”[14.2] is taken to imply that there were two governors in Syria at the same time. But when we read Josephus’ account of another hearing within a year or two of that one, we are given more specific information: it was held before “Saturninus and the senior colleagues of Pedanius, among whom was Volumnius the procurator.”[14.3] The procuratorship was a post held by men of the equestrian class (sometimes even ex-slaves), who were ineligible for the position of governor, and always of inferior rank to the governor (the relationship is similar to that between Quirinius and Coponius, as described by Josephus above). So Volumnius was not and could not have been a governor of Syria, much less co-governor. The second “example” makes essentially the same error.[14.4]

Could Luke mean that Quirinius was prefect of Syria under a superior official? Besides the fact that it is illogical to name the second in command rather than the actual governor, Quirinius had been a Senator of consular rank since 12 B.C. and thus could never have been a prefect, who had to be of equestrian rank (see Two Last Ditch Attempts below). It simply makes far more sense to read Luke as saying just what he says, rather than trying to lap on layers of undemonstrable and implausible hypotheses grounded in nothing but fantasy. The likely fact that Luke is borrowing from Josephus further undermines all such attempts at a solution (cf. Luke and Josephus)..

Was “Quirinius” a Mistake for Someone Else?

Some are tempted to propose the notion that Luke made a mistake: that he really meant Publius Quinctilius Varus rather than Publius Sulpicius Quirinius. Of course, this would entail that Luke is wrong, and thus would admit that the text as we have it (which reads “Quirinius”) contradicts Matthew. And it fails to solve the census problem anyway (as discussed above). But it is also not a plausible conjecture. Around the turn of the 3rd century, it is believed that Tertullian claimed the Lukan census occurred during the tenure of Gaius Sentius Saturninus (who was governor of Syria from 9 to 6 B.C.).[15.1] Of course, Tertullian is not very reliable.[15.2] So the fact that he makes this claim in the context of antiheretical rhetoric is enough to cast doubt on its authority. Moreover, this would have been an easy mistake to make: the governor relieved by Quirinius was Volusius Saturninus, who governed Syria from 4 to 5 A.D.

But this is all moot. For in fact Tertullian does not link Sentius Saturninus with the census in Luke 2:1, as is commonly supposed by those who ignore the context of this passage. Rather, he says censuses (plural, not singular) prove that Jesus had brothers, in defense of Luke 8:19-21. Since Tertullian believed Jesus was the first born, just as Luke says he was, there could not be any record of his brothers in the census of the nativity. Therefore, Tertullian could not possibly have been thinking of the census during which Jesus was born. So he may well mean another Sentius Saturninus (an ancestor of the other), who was governor of Syria in A.D. 19-21 (Tacitus, Annals 2.76-81), a plausible time before which Jesus’ siblings would have been born. For the sentence sed et census constat actos sub Augusto nunc in Iudaea per Sentium Saturninum, apud quos genus eius inquirere potuissent, can be translated “But it is also well known that censuses were conducted under the Augustus in that time in Judaea by Sentius Saturninus, consulting which they can investigate his family.”[15.3] But even if Tertullian meant brothers by a previous marriage, and thus had in mind the previous Sentius Saturninus, this still would not be the census during which Jesus was born, since Jesus had to be born later to a subsequent wife of Joseph. And Tertullian in that case would simply be bluffing, since no census under the first Saturninus would have counted the inhabitants of Judaea (as shown above and below).

So there is no basis for imagining any scribal error in Luke. Certainly, if Luke borrowed his information from Josephus (cf. Luke and Josephus), then he clearly meant Quirinius. And it is not likely that Luke was mistaking the men, rather than making a mistake in writing the name: Quirinius is a cognomen, but Quinctilius is a nomen. In Roman nomenclature there were three names: praenomen (a “first name” or “casual name”), like Publius (the fact that the two men have the same first name cannot explain the mistake–that would be like confusing Kevin Klein with Kevin Sorbo); nomen (“family name,” the equivalent of our last name), like Quinctilius or Sulpicius; and cognomen (like a “nick name” or a traditional name, similar to our middle name), like Varus or Quirinius. It would be odd for an author to confuse one man’s cognomen for another man’s nomen. This is all the more so since Varus was a notoriously famous general, the only one to have lost legions in the early Empire (his three legions were destroyed by Germans in 9 A.D.), a disaster echoing ominously across the Roman world and credited with scaring Augustus into a non-expansionist policy, and leading to the universal glory of Germanicus, beloved all over the empire, who recovered the lost legionary standards in the reign of Tiberius. Why someone like Luke would mistake a famous man for a relatively unknown one is hard to fathom. The reverse would have made more sense. Finally, a mere transcriptional “error” would not likely produce “by chance” the correct name of an actual governor under whom a census was known to be made. But for those die hards who want to argue that anyway, see next. Others can skip it.

|

|

Can it be a Mere Type-o?

| |

Can it be a Mere Type-o?

|

Was it a Census Conducted by Herod the Great?

One might try to argue that the census was actually not Roman at all, but conducted by Herod. Of course, this is prima facie implausible, for it is most strange that Luke would not simply say this, but instead associate it with a Roman governor and an Imperial decree: the plain language and obvious context leaves no reasonable interpretation but that Luke meant a Roman census (and again, the possibility that Luke is drawing on Josephus would support this). Even if some other nations held their own censuses, the Jews held a negative attitude toward taking a census in peacetime.[16.1] Had Herod conducted such a census on his own initiative, it would have been a truly remarkable event, and could not have escaped mention by historians such as Josephus. And Herod the Great enjoyed the greatest favor and freedom of any client king ever under Roman influence, so any Roman attempt to “force” Herod to run a census would have been even more inexplicable and unprecedented.

Nonetheless, Brook Pearson argues for this interpretation and his arguments will be addressed here.[16.2] First, Pearson traps himself in a false dichotomy: arguing that Luke can only be seen as “historically accurate” if Quirinius governed Syria in the reign of Herod or the census took place before Quirinius, he then argues for the latter. But he ignores the easiest solution of all: that Luke is right and Matthew is wrong. Of course, it is just as likely both are wrong, but if one’s goal is to defend Luke, one need only reject the historical accuracy of Matthew. But having set up the goal of defending the only thesis he hasn’t seen refuted, Pearson is left to try and build a case on poorly-researched conjectures. His relevant points are:

• 1 • Pearson claims that “Josephus records a great deal of indirect evidence that a careful and detailed system of census and taxation existed under Herod” (p. 265). But he then presents evidence only of the latter: a careful and detailed system of taxation. He assumes that taxation entailed a census (p. 266). But it did not. Only capitation and corvee taxes (taxes paid per person) required a census. Most taxes had no need of census returns, which were very expensive to administer: land taxes were based on records of property ownership, which were maintained regularly throughout the year; tariffs and other taxes on transportation or sale were levied on the spot; rents of royal land or animals were collected by contractual agreement peculiar to every case; fixed tribute assessed on townships and metropoleis was due in full no matter who had to pay it, and the general point of such taxation was to leave the central power without the expense of having to worry how they came up with it; taxes on produce were based on annual outcomes or predictions, and even when the productivity of land was based on scheduled assessments, this had nothing to do with counting people (and so would not require Joseph to travel).[16.3] What Pearson needs to show is evidence that any sort of capitation or corvee tax was ever levied by Herod, but he doesn’t give a single piece of even indirect evidence of this. Pearson fails to recognize that this is why Egypt had a 14-year census cycle: the only reason a census was taken there at all was that a tax levied on each person began when boys reached the age of 14 (cf. How Often Was the Census Held?, above). There is no evidence of any such cycle or capitation tax in Judaea in the time of Herod, and as noted above it is particularly improbable for a Jewish king, and even more improbable that Josephus should never once mention or allude to such a thing despite covering in detail every year of Herod’s thirty-seven-year reign.

• 2 • Pearson cites Heichelheim on the account books of Herod, claiming they “could not have been possible” without a census (p. 266).[16.4] Of course, Heichelheim’s work is rather outdated, but this conjecture is plainly false from what we know of ancient taxation (as noted above, most taxes required no census) and from the fact that the reference in question is only to records of Herod’s own estates and the annual income of the whole kingdom, which affords no evidence at all of any capitation or corvee taxes (or even land productivity assessments for that matter), and thus provides no evidence of census-taking.[16.5] In fact, one passage Pearson cites implies the opposite: Herod’s kingdom was taxed by assigning fixed annual tribute to each territory, and thus not based on a census. This is clear when Augustus reduces by a quarter the annual tax owed by the whole “Samaritan territory,” rather than, for instance, reducing by a quarter the tax each Samaritan had to pay. In fact, Josephus uses here the word for tribute, which was not capitation or corvee tax but a fixed annual amount levied on cities or groups of cities, who then had to figure out on their own how to come up with it.[16.6]

• 3 • Pearson cites evidence that there were ‘town scribes’ (kômogrammateis) under Herod and therefore census records and therefore a census (p. 271). It never occurs to him to investigate what else such scribes did: for in fact, government-employed scribes kept property records and records of contracts, records pertaining to market taxes and tariffs and and legal cases, and so on, and thus had plenty to do and plenty reason to be in every town. Their existence does not in the least entail a census (indeed, one wonders just what Pearson thinks they did in the years of down-time between censuses). Moreover, not all town scribes were employed by the government: many were private businessmen who read and wrote documents for a fee, hired by the great majority of people, who were illiterate. Thus, once again, non-evidence is blown way out of proportion and turned into a phantom ‘proof’.

• 4 • Pearson tried to dismiss the obvious objection, that Luke refers the census to an Augustan decree and the governorship of Quirinius, by insisting that ancient people dated events by reference to the most memorable event near it, and thus Luke meant to refer to an earlier census by reference to a later ‘more memorable’ one (pp. 277-8). Here all evidence contradicts Pearson, and it is not surprising that he does not give a single analogous example to demonstrate his generalization. Not only would people not have any good idea eighty or so years later when ‘the census of Quirinius’ occurred without reference to some standard chronology, but it was routine to date all events by regnal years of important persons (or, in some places, from the foundation of important cities): coins, handled by everyone, routinely did this, and it would be second nature to understand such a dating scheme. And in fact this is just what Luke does in 3:1. If Luke is comfortable dating events by a precise and normal means there, why would he use an imprecise and abnormal means in 2:1-2? Thus Pearson’s reasoning is entirely shot through. To the contrary, Luke associates the census not with a private action of Herod, but with a decree of Augustus: a Roman action, not a Herodian one. And Luke says it happened when Quirinius was governor of Syria, not before (as has been amply shown above). Indeed, if we follow Rosen, the passage may be taken to mean the first year of Quirinius’ reign, making 2:2 just as precise as 3:1.

The bottom line is that there is no evidence of a Herodian census, and no reason to believe there ever was one. And even if there were, there is no way Luke’s reference could be to such a census, and thus Pearson’s argument is baseless. For the alternative claim that it wasn’t a census but a national oath, see Two Last Ditch Attempts below.