(2003; Updated 2008)

Out-of-Body Discrepancies

Veridical Paranormal Perception During OBEs?

Maria’s Shoe

Pam Reynolds

NDEs in the Blind?

NDE Target Identification Experiments

Psychophysiological Correlates

What are Out-of-Body Experiences?

Bodily Sensations

Living Persons

Cultural Differences

How Consistent are NDE Features across Cultures?

Random Memories

Is the Temporal Lobe Implicated in NDEs?

Threshold Crossings: Returns from the Point of No Return

Who Makes the Decision to Return?

Hallucinatory Imagery

Unfulfilled Predictions: Psychic Inability

Conclusion

Even if we disregard the overwhelming evidence for the dependence of consciousness on the brain, there remains strong evidence from reports of near-death experiences themselves that NDEs are not glimpses of an afterlife. This evidence includes:

(1) discrepancies between what is seen in the out-of-body component of an NDE and what’s actually happening in the physical world;

(2) bodily sensations incorporated into the NDE, either as they are or experienced as NDE imagery;

(3) encountering living persons during NDEs;

(4) the greater variety of differences than similarities between different NDEs, where specific details of NDEs generally conform to cultural expectation;

(5) the typical randomness or insignificance of the memories retrieved during those few NDEs that include a life review;

(6) NDEs where the experiencer makes a decision not to return to life by crossing a barrier or threshold viewed as a ‘point of no return,’ but is restored to life anyway;

(7) hallucinatory imagery in NDEs, including encounters with mythological creatures and fictional characters; and

(8) the failure of predictions in those instances in which experiencers report seeing future events during NDEs or gaining psychic abilities after them.

Out-of-Body Discrepancies

(1) Some NDErs report out-of-body experiences during their NDEs where what is seen ‘out-of-body’ does not correspond to what is actually happening in the physical world. Peter and Elizabeth Fenwick reports the NDE of a World War II veteran whose unit came under attack from aerial bombers:

The battery cook (a devout Muslim) came running in panic toward me…. He lay down, touching my right elbow, and calmed himself…. As I looked up one of the Heinkel pilots executed a tight turn over the rim of the wadi and lined up on us…. I flattened out like a lizard on the sand….

Instantly I was enveloped in a cloud of beautiful purple light and a mighty roaring sound…. and then I was floating, as if in a flying dream, and watching my body, some dozen feet below, lifting off the sand and flopping back, face downwards. I only saw my own body. I was quite unaware of the two Sudanese lying beside me…. And then I was gliding horizontally in a tunnel … rather like a giant, round, luminous culvert, constructed of translucent silken material, and at the end of a circle of bright, pale primrose light. I was enjoying the sensation of weightless, painless flight…. I had a feeling it would be more interesting when I reached the light….

I became aware that I was being ‘sucked’ back through the tunnel and then into a body that felt rather unpleasantly ‘heavy,’ that the sun was burning my back…. [T]he Heinkels were still firing at us and a cannon shell knocked a saucepan off the truck above my head. This troubled me not at all; indeed I seemed to have lost all sense of fear, but my back felt wet and slimy so I looked over my shoulder to investigate the cause. My back was a red mass of blood and raw flesh…. Then I realised that I was looking at all that remained of Osman the cook, who had been lying beside me. I noticed also that my Bren gunner, who had been close to my other side, had disappeared (Fenwick and Fenwick 43-44).

The Fenwicks concede that in this case it is “quite clear” that this NDEr was not actually observing the physical world when he saw his body from above. Obviously this NDE must have been a brain-generated hallucination. Despite their sympathy for the survival hypothesis, the Fenwicks are explicit about the hallucinatory nature of this NDE: “He was unaware of the cook, who had been lying beside him—and was now not simply lying beside him but spread all over his back, where he could hardly have failed to be seen” (Fenwick and Fenwick 44).[1]

(2) The Fenwicks also mention the case of a woman who had 3 spontaneous out-of-body experiences during her second pregnancy (Fenwick and Fenwick 40-41). In her third OBE, she found it difficult to ‘return to her body.’ The Fenwicks write: “Mrs Davey adds that although she was up on the ceiling, she did not see her body” (Fenwick and Fenwick 41).[2]

(3) In a case from “the Evergreen Study” (conducted at Evergreen State College in Washington), a woman had a ruptured Fallopian tube due to an ectopic pregnancy (where a fertilized egg implants and grows in one of the tubes rather than the uterus) and reported seeing things in the room while ‘out-of-body’ which didn’t exist:

I saw this little table over the operating table. You know, those little round trays like in a dental office where they have their instruments and all? I saw a little tray like that with a letter on it addressed (from a relative by marriage she had not met) (Lindley, Bryan, and Conley 109).

The authors report that this woman told her sister-in-law about her NDE, who happened to be a nurse who was called into the operating room at the time of the NDE. But the nurse was adamant that there was neither a letter nor a round table in the operating room.

However, the authors note that there was a small rectangular table for holding instruments in the room called a ‘Mayo’ and quickly deduce a probable scenario for why this experience took the form it did: “Notice [Mayo] sounds like ‘mail.’ She may have heard someone call the tray by name (since hearing is reportedly the final sense to fail at death) and connected it with ‘mail.'” (109). Moreover, the letter seen out-of-body was addressed from the nurse’s brother-in-law, which suggests that she might have heard the nurse’s name and incorporated that information into her experience as well.

What is particularly interesting about this case is not simply that it contains discrepancies, but also that it seems to confirm that out-of-body imagery in NDEs is sometimes obtained directly from scraps of conversation rather than from some paranormal source.

(4) In a study of 264 subjects with sleep paralysis[3], Giorgio Buzzi and Fabio Cirignotta found that about 11% of their subjects (28 people) “viewed themselves lying on the bed, generally from a location above the bed” (Buzzi 2116). As Buzzi points out, however, these out-of-body experiences often included false perceptions of the physical environment:

I invited these people to do the following simple reality tests: trying to identify objects put in unusual places; checking the time on the clock; and focusing on a detail of the scene, and comparing it with reality.

I received a feedback [sic] from five individuals. Objects put in unusual places (eg, on top of the wardrobe) were never identified during out-of-body experiences. Clocks also proved to be unreliable: a woman with nightly episodes of sleep paralysis had two out-of-body experiences in the same night, and for each the clock indicated an impossible time…. Finally, in all cases but one, some slight but important differences in the details were noted: “I looked at ‘me’ sleeping peacefully in the bed while I wandered about. Trouble is the ‘me’ in the bed was wearing long johns … I have never worn such a thing” (Buzzi 2116-2117).

Buzzi concludes that because these experiences contained out-of-body discrepancies and failed his other ‘reality tests,’ his subjects’ out-of-body imagery must have been derived from memory and imagination rather than from the physical environment at the time (2117).

(5) Melvin Morse reports an NDE where a young girl sees her teacher by her body during an OBE when her teacher is not actually there. This case also has other hallucinatory features, such as encountering doctors in an ostensibly transcendental realm:

[O]ne child…. could see her own body as doctors wearing green masks tried to start an IV. Then she saw her living teacher and classmates at her bedside, comforting her and singing to her (her teacher did not visit her in the hospital). Finally, three tall beings dressed in white that she identified as doctors asked her to push a button on a box at her bedside, telling her that if she pressed the green button she could go with them, but she would never see her family again. She pressed the red button and regained consciousness (Morse 68-69).

(6) Using open-ended questions, Morse also found a case where a child that was clinically dead reported that while she was ‘above her body’ looking down, “her mother’s nose appeared flattened and distorted ‘like a pig monster'” (Morse 67).

(7) The Fenwicks recount an NDE where the NDEr ‘observed’ a procedure that never took place during the heart bypass operation she underwent at the time:

[S]he left her body and watched her heart lying beside her body, bumping away with what looked like ribbons coming from it to hands. In fact, this is not what happens in a heart bypass operation, as the heart is left within the chest and is never taken outside the body (Fenwick and Fenwick 193).

The Fenwicks try to explain away this major discrepancy by pointing out that ribbons are indeed tied to arteries during an operation of this sort and by attributing the false perception to misidentification. However, it is difficult to see how a person truly out-of-body with vivid perceptual capabilities could confuse arteries (ribboned or not) with a beating heart lying next to her outside of her body. In the remainder of her experience this NDEr reported ‘traveling’ to a place that looked like an enormous silver ‘airplane hangar’ with tiny figures off in the distance, miles away.

(8) Other NDErs have reported seeing friends out-of-body with them who are, in reality, still alive and normally conscious. The Evergreen Study also recorded a clearly hallucinatory near-death experience after a major car accident:

Well, then I remember, not physical bodies but like holding hands, the two of us, up above the trees. It was a cloudy day, a little bit of clouds. And thinking here we go, we’re going off into eternity… and then bingo, I snapped my eyes open and I looked over and he was staring at me [ellipsis original] (Lindley, Bryan, and Conley 110).

The authors of the study go on to write: “In this incident a woman had lost consciousness but her male companion had not. In the experience, she perceived the two of them in an out-of-body state, yet her friend never blacked out” (110).

(9) OBErs who do not lose consciousness before their experiences often report watching their bodies continue to perform coordinated actions—as if they were still in control of their bodies—while nevertheless apparently viewing them from above. Recalling an OBE while on patrol for the first time, chasing an armed suspect, a police officer reported:

I promptly went out of my body and up into the air maybe 20 feet above the scene. I remained there, extremely calm, while I watched the entire procedure—including watching myself do exactly what I had been trained to do (Alvarado 183).

After the suspect had been restrained and the danger was over, the officer returned to normal consciousness. Another OBEr, who had been running for over 12 miles training for a marathon, reported:

I felt as if something was leaving my body, and although I was still running along looking at the scenery, I was looking at myself running as well (184).

This ability to simultaneously ‘hover’ above the scene and continue to function as if ‘in’ the body strongly suggests the hallucinatory nature of these experiences. In some sleep disorders, for instance, subjects are able to exhibit “directed” behavior—e.g., sleepwalking and sleep eating—even though they are evidently not normally conscious. Taking on an extraordinary new perspective while functioning normally otherwise makes much more sense if such experiences are occurring ‘in’ the body all along, rather than in some remote discarnate entity detached from the physical body.

(10) Finally, Harvey Irwin notes other intriguing examples of hallucinatory OBEs, such as reports of “seeing the physical body as if from a height of 30 feet (9 meters) or more … [when] this would have entailed seeing through the roof and the ceiling of the house” (Irwin, “Introduction” 223). If something leaves the body and perceives the physical world during OBEs, he asked, “why do some OBErs report distortions in reality (e.g., [nonexistent] bars on the bedroom window), and how are some experients able to manipulate the nature and existence of objects in the out-of-body environment by an effort of will?” (233).

As the Fenwicks point out, if OBEs and NDEs are hallucinations,

we should expect there to be major discrepancies between the psychological image—what the person sees from up there on the ceiling, which will be constructed by the brain entirely from memory; and the real image—what is actually going on at ground level. Mrs Ivy Davey, for example, did not see her body, although her body was clearly there (Fenwick and Fenwick 41).

And in the cases above this is exactly what we find. Discrepancies between what’s seen out-of-body and what’s actually happening in the physical world are found in spontaneous OBEs, in NDEs where a real or perceived threat of imminent harm triggers an OBE, and in NDEs that include an OBE along with other NDE components (e.g., a tunnel and light).

Veridical Paranormal Perception During OBEs?

The cases cited in this essay show that many near-death experiences are hallucinations.[4] NDE cases which include false descriptions of the physical environment have been found not only by different near-death researchers, but by researchers searching for evidence that NDEs are not hallucinatory. This motivation among researchers makes it impossible to estimate the prevalence of NDEs with clearly hallucinatory features. As Bruce Greyson points out, the file-drawer problem is a likely factor here: NDE accounts with clearly hallucinatory features may end up filed away indefinitely, while only more dramatic accounts are deemed fit for publication by NDE researchers (Greyson, “Near-Death” 344). Similarly, NDEs with obviously hallucinatory traits seem particularly likely to be underreported by NDErs themselves, given the disparity between how real one’s NDE felt at the time and the realization that it could not possibly reflect reality if, for instance, the NDEr communicated with his still-living mother in an ostensibly transcendental realm. Nevertheless, given that many NDEs are already known to be hallucinations, it is likely that other NDEs are hallucinations as well.

The majority of near-death researchers are interested in the subject because they believe NDEs provide evidence for life after death. Thus near-death researchers generally disregard hallucinatory NDEs while searching for cases of veridical paranormal perception. But at the end of the day, we are left with no compelling evidence that NDErs have actually been able to obtain information from remote locations, and we have clear evidence that NDErs sometimes have false perceptions of the physical world during their experiences.

Mark Fox provides a very balanced assessment of the evidential value of near-death experiences in his recently published Religion, Spirituality and the Near-Death Experience. As a research committee member of the Religious Experience Research Centre at the University of Wales, Lampeter, Fox is certainly no enemy of dualism. Yet he concludes that NDE research to date largely presupposes some sort of dualism rather than providing evidence for it:

This needs to be spelled out loudly and clearly: twenty-five years after the coining of the actual phrase ‘near-death experience,’ it remains to be established beyond doubt that during such an experience anything actually leaves the body. To date, and claims to the contrary notwithstanding, no researcher has provided evidence for such an assertion of an acceptable standard which would put the matter beyond doubt (Fox 340).

In fact, very few cases of ‘veridical perception’ during NDEs have been corroborated. In many cases, details which are said to have been accurate “are not the kind that can easily be checked later” (Blackmore, “Dying” 114). Even the ‘founding father’ of near-death studies, Raymond Moody, concedes that most cases of alleged veridical perception during NDEs are found well after the fact and are usually attested to only by the NDEr and perhaps a few friends (114). And in one study Carlos Alvarado found that although nearly one-fifth of participants claimed to have made “verifiable observations” during their OBEs, only 3 of the 61 cases even “qualified as potentially veridical when experients were asked to provide fuller descriptions” (Alvarado 187).

Susan Blackmore and Tillman Rodabough consider at length how accurate information can be incorporated into realistic out-of-body imagery during NDEs. Both conclude that the primary source of information in the construction of out-of-body imagery is probably hearing. Rodabough notes that patients who appear to be unconscious often repeat earlier comments made by doctors and nurses even without an OBE, and “have even been able to recall operating room conversations under hypnosis” (Rodabough 108). But Blackmore points out that other sensory sources of information are also available to patients. She notes that a residual sense of touch during NDEs could explain accurate details about where defibrillator pads were placed or where chest injections were administered (Blackmore, “Dying” 125).

Remaining out-of-body imagery is probably derived from imagination and general background knowledge. For example, Rodabough points out that childhood socialization trains us to imagine how we appear to others ‘from the outside’; thus visualizing oneself from a third-person perspective comes naturally (Rodabough 108). Blackmore notes that when people are asked to imagine walking down a beach, they usually picture themselves from above, from a bird’s-eye perspective (Blackmore, “Dying” 177). Carol Zaleski suggests that we should expect some NDEs to include OBEs because the most natural way to imagine experiencing one’s death is to imagine looking down on one’s body from above (as people typically do when asked to imagine viewing their own burials). In her lesser-known 1996 book on NDEs, The Life of the World to Come, Zaleski notes:

The people who testify to near-death experience are neither Platonists nor Cartesians, yet they find it natural to speak of leaving their bodies in this way. There simply is no other way for the imagination to dramatize the experience of death: the soul quits the body and yet continues to have a form (Zaleski, “Life” 62-63).

Background knowledge also surely plays a role. Personal experience and media portrayals make it easy for us to imagine what a hospital scene should look like (Rodabough 109). Even specific details about people are fairly predictable in a hospital setting:

When either a person or their roles [sic] is well known, it is not difficult to predict dress or behavior. For example, isn’t it easy to guess that a physician will wear his greens in surgery?[5]… Behavior, particularly where strong emotions are concerned, may be even easier to predict. Mother falls apart and begins to sob hysterically while Dad puts his arms around her in consolation and stoically keeps his anxiety inside…. [Thus] the probability of an accurate description can be high even without an out-of-body experience [emphasis mine] (Rodabough 109).

Blackmore ultimately concludes that “prior knowledge, fantasy and lucky guesses and the remaining operating senses of hearing and touch,” plus “the way memory works to recall accurate items and forget the wrong ones” is sufficient to explain out-of-body imagery in NDEs (Blackmore, “Dying” 115). Cases incorporating out-of-body discrepancies, including those based on misinterpretations of scraps of conversation (e.g., seeing mail in out-of-body imagery when ‘Mayo’ is spoken), appear to confirm this suggestion.

Our memories are constantly reconstructed as we retell stories about our pasts. When a person has an extraordinary story to tell, such as how he found himself out of his body, with all that suggests about the possibility of life after death, the likelihood of exaggeration—even unintentional exaggeration—is obvious. In such cases, ultimately “the version we tell is likely to be just that little bit more interesting or poignant than it might have been” (115).

In fact, most NDE reports are provided to researchers years after the experience itself. Ultimately, all we have to go on is after-the-fact reports of private experiences. The constant reconstruction of memory makes it difficult to know just what NDErs have actually experienced. This problem is clearly recognized by Fox:

[T]he fact that NDErs’ testimonies are indeed retrospectively composed … arouses a suspicion that what NDErs recall—and hence narrate—about their experiences may in fact be different than what they actually experienced during their near-death crises…. [A]ttempting to ascertain what really happens to NDErs—what the core elements of their experiences actually are in and of themselves—may be nigh on impossible to determine…. [W]hat is remembered about an experience or situation may not actually accurately correspond to what was experienced at the time (Fox 197).

Following Zaleski, Fox also wonders to what extent people other than the NDEr play a part in composing an NDE report. Both note, for example, Raymond Moody’s concession that he sometimes used leading questions when interviewing respondents for his 1975 Life After Life (Zaleski, “Otherworldly” 149; Fox 199). Zaleski also points out that after urging his respondents to speak freely, Kenneth Ring would ask specific questions about whether his subjects encountered features of Moody’s model of the NDE, such as: “[W]ere you ever aware of seeing your physical body?” or “Did you at any time experience a light, glow, or illumination?” (Zaleski, “Otherworldly” 105-106). After Sabom allowed his patients to speak freely, he would also “delve for the elements described in Life After Life” (Zaleski, “Otherworldly” 109). One wonders how much similarity would have been found between individual NDE accounts in the West had these early researchers simply asked their respondents to speak freely about their experiences without steering them in a particular direction by probing for Moody’s elements.

This raises further questions about the extent to which other near-death researchers have also used leading interviewing techniques (Fox 199-200). As Greyson points out, how a counselor responds to an NDEr “can have a tremendous influence on whether the NDE is accepted and becomes a stimulus for psychospiritual growth or whether it is regarded as a bizarre experience that must not be shared” [emphasis mine] (Greyson, “Near-Death” 328). While some counselors might take a dismissive attitude to such experiences, many are likely to influence NDErs in the opposite direction, and near-death researchers seem particularly likely to positively reinforce an afterlife interpretation of NDEs. This may be one reason why so many NDErs accept that interpretation. Another may be that widespread belief in an afterlife among the general population has already primed NDErs to interpret unusual experiences on the brink of death in terms of an afterlife. And on top of such outside influences, Fox notes:

[Simply] having an experience which may appear to the subject to point to the possibility of immortality—such as an OBE whilst resting or sleeping, leading to the conviction that the soul can function independently of the body—may suffice to instil in him or her an often strong and permanent belief that personal death is not the end…. And often their experiences are so vivid as to provide, for them, a solid basis for drawing conclusions across a wide range of important, existential issues: including the question of their own immortality and its relationship to the way they live and understand their lives before their deaths (Fox 287).

Taking an afterlife interpretation largely explains the transformative effects of NDEs on those who have them as well. (Though to gauge the extent of this, it would be interesting to see if “nonbelievers” had the same transformations as “survivalists” among NDErs.)[6]

Rodabough explains how unintentional interviewer feedback can contaminate NDE reports:

[I]f the resuscitated person gives a partially accurate account of some event taking place while he was “out,” the questioner may unintentionally give information which the resuscitated person unknowingly fits into his story. To some degree, we can visualize what we are told and not be sure which occurred first…. This is likely to occur if the questioner wants to hear things a particular way and nonverbally reinforces the respondent when he hears what he wants. The high enthusiasm of the interviewer may unwittingly entice the respondents to embellish their experiences, and low enthusiasm may influence respondents to remain silent about puzzling or unusual experiences (Rodabough 109-110).

In fact, in recent years a large number of NDE reports have been garnered from NDE support groups. Support group members have almost certainly shaped the content of individual NDE accounts through “biographical reshaping, deepening of commitment, and reinforcement of group belief” (Fox 201).

In The Truth in the Light, the Fenwicks asks how an experience as coherent as an NDE could be generated in a disorganized dying brain, and how it could be encoded for vivid recall later:

How is it that this coherent, highly structured experience sometimes occurs during unconsciousness, when it is impossible to postulate an organized sequence of events in a disordered brain? One is forced to the conclusion that either science is missing a fundamental link which would explain how organized experiences can arise in a disorganized brain, or that some forms of experience are transpersonal—that is, they depend on a mind which is not inextricably bound up with the brain (Fenwick and Fenwick 235).[7]

But as Gerald Woerlee points out, lack of oxygen to the brain blunts a subject’s judgment, creating a false confidence in one’s abilities and a false sense that one’s thinking is particularly keen—a well-known fact exhibited in the statements of clearly impaired drunk drivers. “This,” he argues, “is why people recovering from cardiac resuscitation never say their mental state during a period of consciousness such as an NDE was confused or befuddled” (Woerlee, “Cardiac” 246).

Greyson offers a related argument:

[O]rganic brain malfunctions generally produce clouded thinking, irritability, fear, belligerence, and idiosyncratic visions, quite unlike the exceptionally clear thinking, peacefulness, calmness, and predictable content that typifies the NDE. Visions in patients with delirium are generally of living persons, whereas those of patients with a clear sensorium as they approached death are almost invariably of deceased persons [emphasis mine] (Greyson, “Near-Death” 334).

But as we see in the case of G-LOC dreamlets (pleasurable experiences caused by lack of oxygen to the brain during pilot blackouts), some “organic brain malfunctions” clearly produce hallucinatory experiences characterized by clarity of thought, euphoria, and the ‘realness’ feel of the experience. As James E. Whinnery has reported, hypoxic G-LOC episodes have some similarities to NDEs, such as floating sensations, OBEs, visions of lights, and “vivid dreamlets of beautiful places that frequently include family members and close friends, pleasurable sensations, euphoria, and some pleasurable memories” (Greyson, “Near-Death” 334). The ability to consistently induce these dreamlets in pilot centrifuges should have dispelled the myth that hypoxic hallucinations are nearly always frightening, confused, or disoriented. And the prevalence of visions of the deceased in NDEs is not surprising: patients who merely have delirium are not dying and have no particular expectation of dying. For the same reason, it should not be surprising that G-LOC dreamlets do not share other NDE features. The context of NDEs is much different, as the sensation or expectation of dying is much more likely in near-death contexts. And while Greyson points out that NDErs who had hallucinations prior to their NDEs describe their NDE worlds as “‘more real’ than the world of waking hallucinations” (334), the proper comparison is between NDEs and (very vivid and realistic) hallucinations that follow a loss of consciousness (e.g., dreams), not waking hallucinations.

In their prospective study of NDEs published in Lancet, Pim van Lommel and colleagues argue that NDE-like hallucinations induced in the laboratory are simply too fragmented to be comparable to NDEs (van Lommel et al. 2044). So why do NDErs recall such vivid experiences, rather than fragments of memories, if NDEs are hallucinations? Fox suggests that the answer does not lie in what is happening to the brain during the NDE, but in how NDE reports are reshaped afterward:

[I]t is clearly probable that both the structured story which at least some NDErs tell and its vividness and clarity may both stem from a variety of sources other than the purely private experiences of the NDErs themselves…. [P]lot and detail may potentially hail from a wide range of sources, including … the behavior of near-death researchers themselves as they attempt to draw out a story along already existing and fixed lines, and the processes which have been seen to exist when the NDEr’s story is told and retold before groups (which may themselves interact in the process of composition and reshaping of the original traveller’s tale) (Fox 203).

In fact, the comments of NDErs themselves provide evidence that NDE accounts become more elaborate over time while NDErs’ commitment to the reality of their experiences deepens. After 23 years of trying to determine the significance of her NDE, one woman commented: “It was real then. It is more real now” (Zaleski, “Otherworldly” 150). Another NDEr noted that what he understood and remembered about his NDE had grown over the years by relating the story to others (150). In one of the more reliable studies of NDE incidence and transformation, van Lommel and colleagues found that the transformations widely believed to occur after NDEs actually do occur[8], but that “this process of change after NDE tends to take several years to consolidate” (van Lommel et al. 2043). In other words, the transformative effect of NDEs on experients is not immediate, but gradual.[9] This suggests that NDE transformations do not result from the NDE itself, but from reflecting on the meaning of the experience—that is, from the added layers of meaning and interpretation experients’ place on their NDEs.

Rense Lange, Bruce Greyson, and James Houran have even found suggestive statistical evidence for embellishment. In the process of establishing that the Greyson NDE Scale can reliably diagnose and measure the depth of NDEs, the researchers made a curious discovery about their sample of NDErs. Plotting data on when an NDE occurred against when it was reported, they found that “when reported at a later age (50 years or older) NDE[s] appear more intense then when reported earlier (49 or younger), and the intensity of the reported NDE[s] increased with their latency (shorter vs. longer than 15 years)” (Lange, Greyson, and Houran 168). In other words, the longer the delay between having the experience and reporting it, the more intense the NDE that was reported. As the authors note, however, these findings conflict with those of a similar study by Carlos Alvarado and Nancy Zingrone, and David Lester found no correlation between NDE depth (as measured by Kenneth Ring’s Weighted Core Experience Index) and length of delay between the NDE and when it was reported (172). Consequently, the discovery of embellishment in the Lange-Greyson-Houran study may have been peculiar to that particular sample of NDErs, rather than a finding that should be generalized to all NDErs. The authors suggest longitudinal studies to definitively determine the extent of embellishment in NDEs (173).[10]

Further evidence that NDE accounts are continually reshaped over time to make them more coherent and interesting comes from comparisons between the NDEs reported by adults and those reported by children. Childhood NDE reports almost always consist only of memory fragments (Morse 68). Both the Fenwicks and Morse found that childhood NDEs tend to be much more fragmentary than those of adults. This makes sense, for children have fewer conceptual resources to draw on and so are much less likely to incorporate unconscious embellishments in their accounts when recalling their NDEs.

Given fragmentary experiences of any sort, the brain will often fill in the gaps with plausible guesses about what happened in the missing intervals in order for an experience to make sense. Human memory relies on plausible after-the-fact reconstructions of events that often incorporate details invented by the subject, details which were never actually experienced. For example, a witness may provide a description of a robber wearing the wrong color of clothing. Since adults have already developed complex ways of making sense of their experiences, while children have comparably simple thought processes, it would not be surprising for adult NDErs to unconsciously embellish reports of their experiences with after-the-fact interpretations of them. This seems to be the most likely explanation for why adult NDE reports are so vivid and structured, flowing seamlessly from one NDE element to another, while childhood NDEs tend to be fragmentary.

Van Lommel and colleagues open their discussion of the results of their landmark longitudinal study with an argument against physiological explanations for NDEs:

Our results show that medical factors cannot account for [the] occurrence of [the] NDE; although all [of our] patients had been clinically dead, most did not have [an] NDE. Furthermore, seriousness of the crisis was not related to occurrence or depth of the experience. If purely physiological factors resulting from cerebral anoxia caused [the] NDE, most of our patients should have had this experience (2043).

One possible answer to this argument is anticipated in Blackmore’s model of the NDE: There are different kinds of anoxia, and rate of onset, amount of time before oxygen restoration, and similar factors have to fall within the right ranges before an NDE can take place.[11] Apparently, for the vast majority of cardiac arrest survivors, this does not happen, and so NDEs are rare among them, no matter how close they come to death as measured by some objective criterion. Another possible answer, perhaps complementary to Blackmore’s, is suggested by Britton and Bootzin’s research: If only a small minority of those who come close to death are physiologically predisposed to have NDEs, the vast majority will experience nothing—and this is exactly what we find.

On the other hand, what of the alternative explanation? If NDEs were really glimpses of an afterlife, why is it that only a fraction of those who come close to death (about 10-20% per van Lommel et al.) report them?[12] Physiology provides a ready answer: Woerlee has calculated that around 20-24% of those undergoing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) have some degree of consciousness restored during CPR, a fraction of whom could be having NDEs precisely because the conditions are ripe for an altered state of consciousness (Woerlee, “Cardiac” 233, 244). And why aren’t NDEs consistently reported (nearly 100% of the time) after the controlled induction of hypothermic cardiac arrest or “standstill,” where patients are clinically dead for up to an hour?[13] The vast majority of those who come as close to death as possible without actually dying experience nothing at all (van Lommel et al. 2041). If NDEs are to be understood as glimpses of an afterlife, are we to conclude that 80% of individuals cease to exist when they die, while the remaining 20% survive bodily death?

While some NDErs claim to accurately see things they could not possibly see from their bodies, such anecdotes are difficult to corroborate, and it would not be surprising if NDErs consciously or unconsciously exaggerated the accuracy of their descriptions in order to validate their experiences. As we shall see later, many NDErs are already known to exaggerate claims about their psychic abilities after their NDEs; so it would not be surprising for them to exaggerate claims about what they saw during their out-of-body experiences as well.

The near-death literature is filled with anecdotes of NDErs providing accurate details about events they could not have possibly learned about through normal means. But as I hope to make clear, claims of unequivocal paranormal perception during NDEs are greatly exaggerated. Let’s take a closer look at a few well-known cases widely held to provide such evidence.

Maria’s Shoe

In 1984 Kimberly Clark (now Kimberly Clark Sharp) reported a sensational case of apparent veridical paranormal perception during an NDE. Seven years earlier, in April 1977, an out-of-town migrant worker known only as “Maria” was admitted to the coronary care unit of Seattle’s Harborview Medical Center after a heart attack. Three days later, Maria had a second heart attack while still hospitalized and was quickly resuscitated. When Clark came to check on Maria’s condition later that day, Maria reported an OBE where she witnessed her resuscitation from above, noting printouts flowing from the machines monitoring her vital signs. Next she reported becoming distracted by something over the area surrounding the emergency room entrance and ‘willing herself’ outside of the hospital. She accurately described the area surrounding the emergency room entrance, which Clark found curious since a canopy over the entrance would have obstructed Maria’s view if she had simply looked out of her hospital room window. Maria then became distracted by something on a third-floor window ledge on the far side of the hospital, ‘willing herself’ to this location as well. From this apparent vantage point, she noted a left-foot man’s tennis shoe on a third-floor window ledge. She described the shoe as dark blue with a worn-out patch over the little toe and a single shoelace tucked under its heel. To corroborate her story, Maria asked Clark to go look for the shoe (Clark 242-243).

Unable to see anything from outside the hospital at ground level, Clark reports, she proceeded to search room-to-room on the floor above Maria’s room, pressing her face hard against the windows to see their ledges. Eventually she came across the reported shoe in one of the rooms, but insisted that she could not see the worn-out toe facing outward or the tucked-in shoelace from inside the room. Clark then removed the shoe from the ledge (243). Kenneth Ring and Madelaine Lawrence hail the report as one of most convincing cases of veridical paranormal perception during NDEs on record:

[T]he facts of the case seem incontestable. Maria’s inexplicable detection of that inexplicable shoe is a strange and strangely beguiling sighting of the sort that has the power to arrest the skeptic’s argument in mid-sentence, if only by virtue of its indisputable improbability (Ring and Lawrence 223).

This case has taken on the status of something of an urban legend, allegedly demonstrating that Maria learned things during her OBE that she could not have possibly known about other than by actually leaving her body. But as Hayden Ebbern, Sean Mulligan, and Barry Beyerstein make clear, the details Maria reported were in fact quite accessible to her through ordinary sense perception and inference.

In 1994 Ebbern and Mulligan visited Harborview to survey the sites where the NDE took place and to interview Clark. They were unable to locate “Maria” or anyone who knew her personally and suspect that she is now deceased (Ebbern, Mulligan, and Beyerstein 30). They examined each of the details of Clark’s report and found the case much less impressive than it has been made out to be. First, after being hospitalized for three days, Maria would have been quite familiar with the equipment monitoring her; so her perception of the printouts during her OBE may be nothing more than “a visual memory incorporated into the hallucinatory world that is often formed by a sensory-deprived and oxygen-starved brain” (31). Second, her perception of details concerning the area surrounding the emergency room entrance were of details that “common sense would dictate”—such as the fact that the doors opened inward, accommodating paramedics rushing in patients who need immediate attention (31). Moreover, she was brought into the hospital through this very entrance—albeit at night, but the area was well-lit—and could’ve picked up details about it from normal sensory channels then (31-32). The fact that rushing ambulances would traverse a one-way driveway, too, is something anyone could infer from common sense. Finally, Maria’s hospital room was just above the emergency room entrance for a full three days before she had her OBE, and “she could have [easily] gained some sense of the traffic flow from the sounds of the ambulances coming and going” and from nighttime “reflections of vehicle lights” even if she never left her bed (32).

But what of the most persuasive aspect of her report—her description of the celebrated shoe? How difficult would it have been for her to learn these details without having left her body? Ebbern and Mulligan set out to determine exactly that:

As part of our investigation, Ebbern and Mulligan visited Harborview Medical Center to determine for themselves just how difficult it would be to see, from outside the hospital, a shoe on one of its third-floor window ledges. They placed a running shoe of their own at the place Clark described and then went outside to observe what was visible from ground level. They were astonished at the ease with which they could see and identify the shoe.

Clark’s claim that the shoe would have been invisible from ground level outside the hospital is all the more incredible because the investigators’ viewpoint was considerably inferior to what Clark’s would have been seventeen years earlier. That is because, in 1994, there was new construction under way beneath the window in question and this forced Ebbern and Mulligan to view the shoe from a much greater distance than would have been necessary for Clark (32).

As the authors note, what was a construction area for them in 1994 was a high-traffic parking lot and recreation area back in 1977, providing an even better view of Maria’s shoe than the one they saw so easily. Their 1994 ‘test shoe’ was so conspicuous, in fact, that by the time they returned to the hospital one week later, “someone not specifically looking for it” had noticed it and removed it (32). It is quite likely, then, “that anyone who might have noticed the shoe back in 1977 would have commented on it because of the novelty of its location” and Maria could have heard such a conversation and consciously forgotten about it, incorporating it into her out-of-body imagery (32). Moreover, even if no one had seen it from the ground level, Ebbern and Mulligan tested Clark’s claim that Maria’s shoe was impossible to see from inside the room unless she pressed her face hard against the glass looking for it. This claim was found to be wanting:

They easily placed their running shoe on the ledge from inside one of the rooms and it was clearly visible from various points within the room. There was no need whatsoever for anyone to press his or her face against the glass to see the shoe. In fact, one needed only to take a few steps into the room to be able to see it clearly. To make matters worse for Clark’s account, a patient would not even need to strain to see it from his or her bed in the room. So it is apparent that many people inside as well as outside the hospital would have had the opportunity to notice the now-famous shoe, making it even more likely that Maria could have overheard some mention of it (32).

The authors add that anyone who did press his or her face against the glass to get a closer look at the conspicuous shoe from inside the room could easily see the worn-out little toe and tucked shoelace: “we had no difficulty seeing the shoe’s allegedly hidden outer side” (32). They conclude:

[Maria’s shoe] would have been visible, both inside and outside the hospital, to numerous people who could have come into contact with her. It also seems likely that some of them might have mentioned it within earshot….

[And Clark] did not publicly report the details of Maria’s NDE until seven years after it occurred. It is quite possible that during this interval some parts of the story were forgotten and some details may have been interpolated…. [Moreover], we have no way of knowing what leading questions Maria may have been asked, or what Maria might have “recalled” that did not fit and was dropped from the record (32-33).

Furthermore, Clark’s inaccurate account of how difficult the shoe was to see from both inside and out provides evidence that she subconsciously embellished significant details to bolster the apparently veridical nature of the case (33).

Pam Reynolds

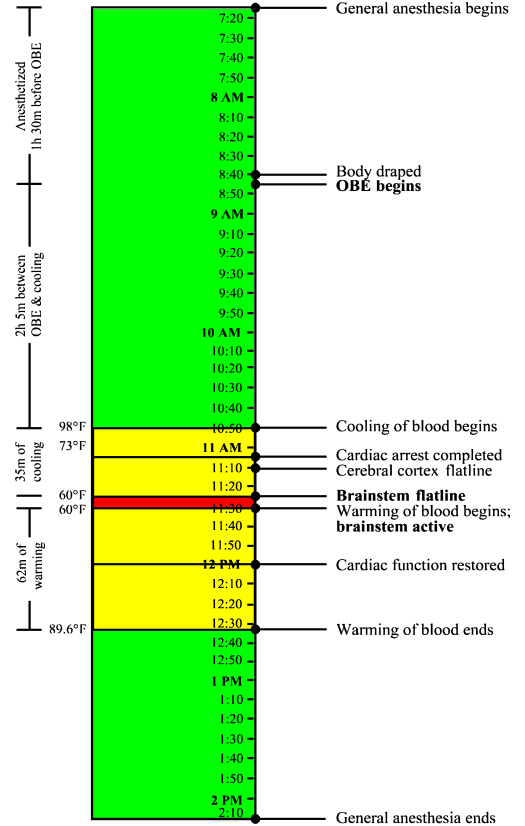

As Michael Sabom recounts in Light and Death, in August 1991 a then 35-year-old woman he called “Pam Reynolds” (a pseudonym) underwent an innovative procedure to remove a brain aneurysm. The procedure—inducing hypothermic cardiac arrest or “standstill”—involved lowering Pam’s body temperature to 60°F, stopping her heart and breathing, and draining the blood from her brain to cool it and then reintroduce it. When her body temperature had reached 60°F and she had no electrical activity in her brain, her aneurysm was removed. About 2 hours after awaking from general anesthesia, Pam was moved into the recovery room still intubated (Sabom, “Light” 46-47). At some point after that, the tube was removed from her trachea and she was able to speak. She reported a classic NDE with a vivid OBE, moving through a “tunnel vortex” toward a “pinpoint of light” that continually grew larger, hearing her deceased grandmother’s voice, encountering figures in a bright light, encountering deceased relatives who gave her “something sparkly” to eat, and being ‘returned’ to her body by her deceased uncle (Sabom, “Light” 42-46).

The case was quickly celebrated because of the lack of synaptic activity within the procedure and Pam’s report of an apparently veridical OBE at some point during the operation. But it has been sensationalized at the expense of the facts, facts which have been continually misrepresented by some parapsychologists and near-death researchers.[14] Although hailed by some as “the most compelling case to date of veridical perception during an NDE” (Corcoran, Holden, and James), and “the single best instance we now have in the literature on NDEs to confound the skeptics” (Ring, “Religious Wars” 218), it is in fact best understood in terms of normal perception operating during an entirely nonthreatening physiological state.

Two mischaracterizations of this case are particularly noteworthy, as their errors of fact greatly exaggerate the force of this NDE as evidence for survival after death.[15] First, in their write-up of the first prospective study of NDEs, van Lommel and colleagues write:

Sabom mentions a young American woman who had complications during brain surgery for a cerebral aneurysm. The EEG [electroencephalogram] of her cortex and brainstem had become totally flat. After the operation, which was eventually successful, this patient proved to have had a very deep NDE, including an out-of-body experience, with subsequently verified observations during the period of the flat EEG [emphasis mine] (van Lommel et al. 2044).

Second, in his Immortal Remains—an assessment of the evidence for survival of bodily death—Stephen Braude erroneously describes the case as follows:

Sabom reports the case of a woman who, for about an hour, had all the blood drained from her head and her body temperature lowered to 60 degrees. During that time her heartbeat and breathing stopped, and she had both a flat EEG and absence of auditory evoked potentials from her brainstem…. Apparently during this period she had a detailed veridical near-death OBE [emphasis mine] (Braude 274).

But anyone who gives Sabom’s chapters on the case more than a cursory look will see two glaring errors in the descriptions above. First, it is quite clear that Pam did not have her NDE during any period of flat EEG.[16] Indeed, she was as far as a patient undergoing her operation could possibly be from clinical death when her OBE began.[17] Second, she had no cerebral cortical activity for no longer than roughly half an hour. Both of these facts are nicely illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Despite accurately reporting the facts, Sabom himself has encouraged these misrepresentations.[18] Though he informs the reader that Pam’s experience began well before standstill, he reveals this incidentally, so that a careful reading of the text is required to discern the point. For instance, just after describing Pam’s recollections of an operating room conversation, he notes, almost as an afterthought, that “[h]ypothermic cardiac arrest would definitely be needed” [emphasis mine] (Sabom, “Light” 42). He then goes on to assert that the very features of her experience which cannot be timed happened during standstill. At first, Sabom only implies this by describing the cooling of blood leading to standstill prior to describing the remainder of Pam’s near-death experience (42-46). Then Sabom turns to a discussion of whether Pam was “really” dead during a portion of her standstill state:

But during “standstill,” Pam’s brain was found “dead” by all three clinical tests—her electroencephalogram was silent, her brain-stem response was absent, and no blood flowed through her brain. Interestingly, while in this state, she encountered the “deepest” near-death experience of all Atlanta Study participants….

With this information, can we now scientifically assert that Pam was either dead or alive during her near-death experience? Unfortunately, no. Even if all medical tests certify her death, we would still have to wait to see if life was restored [emphasis mine] (Sabom, “Light” 49).

Of course, the issue of whether Pam was “really” dead within standstill is an extraordinarily misleading red herring in this context. And it is blatantly irresponsible for Sabom to explicitly state that her NDE occurred “while in this state.” As Sabom’s own account reveals, her standstill condition had absolutely nothing to do with the time when we know that her near-death OBE began: A full two hours and five minutes before the medical staff even began to cool her blood, during perfectly normal body temperature![19] (Again, see Figure 1.)

Unlike the other elements of her NDE, we can precisely time when Pam’s OBE began because she did accurately describe an operating room conversation. Namely, she accurately recalled comments made by her cardiothoracic surgeon, Dr. Murray, about her “veins and arteries being very small” (Pam’s words) (Sabom, “Light” 42). Two operative reports allow us to time this observation. First, in the head surgeon’s report, Dr. Robert Spetzler noted that when he was cutting open Pam’s skull, “Dr. Murray performed bilateral femoral cut-downs for cannulation for cardiac bypass” (185). So at about the same time that Dr. Spetzler was opening Pam’s skull, Dr. Murray began accessing Pam’s blood vessels so that they could be hooked up to the bypass machine which would cool her blood and ultimately bring her to standstill. Second, Dr. Murray’s operative report noted that “the right common femoral artery was quite small” and thus could not be hooked up to the bypass machine. Consequently, Murray’s report continues, “bilateral groin cannulation would be necessary: This was discussed with Neurosurgery, as it would affect angio access postoperatively for arteriography” (185). And although Pam’s mother was given a copy of the head surgeon’s operative report (which she said Pam did not read), the report did not say anything about any of Pam’s arteries being too small (Sabom, “Shadow” 7).

Many have argued that Pam’s accurate recall of an operating room conversation is strong evidence that she really did leave her body during the procedure. But there is at least one peculiar fact about Pam’s recollections—in addition to the timing of her experience—which makes a physiological explanation of her OBE much more likely.

General anesthesia is the result of administering a trio of types of drugs: sedatives, to induce sleep or prevent memory formation; muscle relaxants, to ensure full-body paralysis; and painkillers. Inadequate sedation alone results in anesthesia awareness. Additionally, if insufficient concentrations of muscle relaxants are administered, a patient will be able to move; and if an inadequate amount of painkillers are administered, a patient will be able to feel pain (Woerlee, “Anaesthesiologist” 16). During a typical surgical procedure, an anesthesiologist must regularly administer this trio of drugs throughout the operation. But just prior to standstill, anesthetic drugs are no longer administered, as deep hypothermia is sufficient to maintain unconsciousness. The effects of any remaining anesthetics wear off during the warming of blood following standstill (G. Woerlee, personal communication, November 8, 2005).

About one or two in a thousand patients undergoing general anesthesia report some form of anesthesia awareness. That represents between 20,000 and 40,000 patients a year within the United States alone. A full 48% of these patients report auditory recollections postoperatively, while only 28% report feeling pain during the experience (JCAHO 10). Moreover, “higher incidences of awareness have been reported for caesarean section (0.4%), cardiac surgery (1.5%), and surgical treatment for trauma (11-43%)” (Bünning and Blanke 343). Such instances must at least give us pause about attributing Pam’s intraoperative recollections to some form of out-of-body paranormal perception. Moreover, for decades sedative anesthetics such as nitrous oxide have been known to trigger OBEs.

Sometime after 7:15 AM that August morning, general anesthesia was administered to Pam Reynolds. Subsequently, her arms and legs were tied down to the operating table, her eyes were lubricated and taped shut, and she was instrumented in various other ways (Sabom, “Light” 38). A standard EEG was used to record activity in her cerebral cortex, while small earphones continuously played clicks[20] into her ears to invoke auditory evoked potentials (AEPs), a measure of activity in the brain stem (39).

Sabom considers whether conscious or semiconscious auditory perceptions were incorporated into Pam’s OBE imagery during a period of anesthesia awareness, but dismisses the possibility all-too-hastily:

Could Pam have heard the intraoperative conversation and then used this to reconstruct an out-of-body experience? At the beginning of the procedure, molded ear speakers were placed in each ear as a test for auditory and brain-stem reflexes. These speakers occlude the ear canals and altogether eliminate the possibility of physical hearing (Sabom, “Light” 184).

But is this last claim really true? Since Sabom merely asserts this (and has an obvious stake in it being true), we have little reason to take him at his word—especially on such a crucial point. What is the basis for his assertion? Does he have any objective evidence that the earphones used to measure AEPs completely cut off sounds from the external environment?

Since Sabom does not back up this claim in Light and Death, I did a little research and discovered that his claim is indeed false. According to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, as a matter of procedure, a patient who is monitored by the very same equipment to detect acoustic neuromas (benign brain tumors) “sits in a soundproof room and wears headphones” (NINDS). But a soundproof room would be unnecessary, of course, if the earphones used to measure AEPs “occlude the ear canals and altogether eliminate the possibility of physical hearing.” It is theoretically possible that the earphones used in 1991 made physical hearing impossible, whereas the earphones used today do not. However, it highly unlikely, as it would be far cheaper for medical institutions to continue to invest in the imagined sound-eliminating earphones, rather than soundproofing entire rooms to eliminate external sounds. As Gerald Woerlee points out, “earplugs do not totally exclude all external sounds, they only considerably reduce the intensity of external sounds,” as demonstrated by “enormous numbers of people … listening to loud music played through earplugs, while at the same time able to hear and understand all that happens in their surroundings” (Woerlee, “Pam”).

After being prepped for surgery, Pam’s head was secured by a clamp. By 8:40 AM, her entire body was draped except for her head (the site of the main procedure) and her groin (where blood vessels would be hooked up to the bypass machine to cool her blood). In the five minutes or so to follow, Dr. Spetzler would open her scalp with a curved blade, fold back her scalp, then begin cutting into her skull with a Midas Rex bone saw (39-41). At this point, about an hour and a half after being anesthetized, Pam’s OBE began (185). She reported being awakened by the sound of a natural D, then being “pulled” out of the top of her head by the sound (41).

“But,” Sabom asks, “was Pam’s visual recollection from her out-of-body experience accurate?” (186). That is indeed the question to ask regarding the veridicality of her report.

Pam reported that during her OBE, she was able to view the operating room from above the head surgeon’s shoulder, describing her out-of-body vision as “brighter and more focused and clearer than normal vision” (41). In her report of the experience, she offered three verifiable visual observations. First, she said that “the way they had my head shaved was very peculiar. I expected them to take all of the hair, but they did not.” Second, she reported that the bone saw “looked like an electric toothbrush and it had a dent in it, a groove at the top where the saw appeared to go into the handle, but it didn’t.” Finally, she noted that “the saw had interchangeable blades … in what looked like a socket wrench case” (41). Subsequently, she only reported auditory observations—hearing the bone saw “crank up” and “being used on something”—but most notably the operating room conversation initiated by Dr. Murray.

Given such vivid ‘perceptual capabilities’ during her OBE, we would expect there to be no confusion about what Pam saw during the experience. So her visual observations provide an interesting test of the notion that her soul left her body while under general anesthesia during normal body temperature. Let us look at each of these in turn.

First, there is the observation that only part of her head was shaved. Perhaps she could have guessed this at the time of her experience, but there is no need even for this in order to account for the reported observation. Surely Pam would have noticed this soon after awaking from general anesthesia—by seeing her reflection, feeling her hair, or being asked about it by visitors. And she certainly would have known about it, one way or the other, by the time she was released from the hospital. Indeed, if her hair had been shaved presurgery, or at any time prior to her general anesthesia, she would have known about it well before her OBE. And patients undergoing such a risky procedure are standardly given a consent briefing where even the cosmetic effects of surgery are outlined—if not explicitly in a doctor’s explanation, then at least incidentally in any photographs, diagrams, or other sources illustrating what the procedure entails. So Pam may have learned (to her surprise) that her head would be only partially shaved in a consent briefing prior to her experience, but ‘filed away’ and consciously forgot about this information given so many other more pressing concerns on her mind at the time. That would be exactly the sort of mundane, subconscious fact we would expect a person to recall later during an altered state of consciousness.[21] And although we are not given the exact date of the operation, Sabom reports that the procedure took place in August 1991 (38). He later tells us that he interviewed Pam for the first time on November 11, 1994 (186). That leaves over three years between the date of Pam’s NDE and Sabom’s interview—plenty of time for memory distortions to have played a role in her report of the experience. So there is nothing remarkable about this particular observation.

Second, there is her description of the bone saw. But the very observation that provides the greatest potential for supporting the notion that she actually left her body during her OBE actually tends to count against that hypothesis. As Sabom recounts,

Pam’s description of the bone saw having a “groove at the top where the saw appeared to go into the handle” was a bit puzzling…. [T]he end of the bone saw has an overhanging edge that [viewed sideways] looks somewhat like a groove. However, it was not located “where the saw appeared to go into the handle” but at the other end.

Why had this apparent discrepancy arisen in Pam’s description? Of course, the first explanation is that she did not “see” the saw at all, but was describing it from her own best guess of what it would look and sound like (187).

Precisely! Except that, of course, Pam didn’t need to guess what the bone saw sounded like, since she probably heard it as anesthesia failed. An out-of-body discrepancy within Pam’s NDE prima facie implies the operation of normal perception and imagination within an altered state of consciousness. Indeed, this explanation is so straightforward that Sabom considers it before all others. And it is telling that the one visual observation that Pam (almost) could not have known about other than by leaving her body was the very detail that was not accurate.

Let us turn to the report of Pam’s final visual observation during her OBE, her comment that the bone saw used “interchangeable blades” placed inside something “like a socket wrench case.” This detail was also accurate; however, one need not invoke paranormal perceptual capabilities to explain it. As Woerlee notes,

[S]he knew no-one would use a large chain saw or industrial angle cutter to cut the bones of her skull open…. Pneumatic dental drills with the same shapes, and making similar sounds as the pneumatic saw used to cut her skull open, were in common use during the late 1970s and 1980s. Because she was born in 1956, a generation whose members almost invariably have many fillings, Pam Reynolds almost certainly had fillings or other dental work, and would have been very familiar with the dental drills. So the high frequency sound of the idling, air-driven motor of the pneumatic saw, together with the subsequent sensations of her skull being sawn open, would certainly have aroused imagery of apparatus similar to dental-drills in her mind when she finally recounted her remembered sensations. There is another aspect to her remembered sensations—Pam Reynolds may have seen, or heard of, these things before her operation. All these things indicate how she could give a reasonable description of the pneumatic saw after awakening and recovering the ability to speak (Woerlee, “Anaesthesiologist” 18).

And, predictably enough, the dental drills in question also used interchangeable burs stored in their own socket-wrench-like cases.

During anesthesia awareness, and as far from standstill as a person under general anesthesia can be, Pam could have heard her surroundings, but not seen them, since her eyes were taped shut. And the facts of her case strongly suggest that this is exactly what happened. Information that she could have obtained by hearing was highly accurate; at the same time, information that was unavailable to her through normal vision was the very information which was inaccurate. More precisely, her visual descriptions were only partially accurate: accurate on details she could have plausibly guessed or easily learned about subsequent to her experience, and inaccurate on details that it would be difficult to guess correctly.

In other words, OBE imagery derived from hearing and background knowledge, perhaps coupled with the reconstruction of memory, fully accounts for the most interesting details of Pam Reynolds’ NDE report. After awakening from inadequate anesthesia by the sound of the bone saw revving up, her mind generated a plausible image of what the bone saw used during her operation looked like, rendered from her prior knowledge of similar-sounding dental drills. But her best guess about the appearance of the bone saw was inaccurate regarding the features of the bone saw that only true vision could discern: whether there was a true groove in the instrument, and where it was located.

Moreover, the fact that Pam’s NDE began during an entirely nonthreatening physiological condition—under general anesthesia at normal body temperature—implies that there was no particular physiological trigger for the experience (such as anoxia/hypoxia). Rather, it appears that her NDE was entirely expectation-driven. Before going into surgery, Pam was fully aware that she would be taken to the brink of death while in the standstill state. Awakening from general anesthesia by the sound of the bone saw appears to have induced a fear response, which in turn caused Pam to dissociate and have a classic NDE. Indeed, this makes sense of her otherwise odd report of being pulled out of the top of her head by the sound of the saw itself.

At least five separate studies (Gabbard, Twemlow, and Jones; Stevenson, Cook, and McClean-Rice; Gabbard and Twemlow; Serdahely, “Variations”; Floyd) have documented cases where fear alone triggered an NDE. As Ian Stevenson, Emily Williams Cook (now Emily Williams Kelly), and Nicholas McClean-Rice conclude, “an important precipitator of the ‘near-death experience’ is the belief that one is dying—whether or not one is in fact close to death” (Stevenson, Cook, and McClean-Rice 45). They go on to label those (otherwise indistinguishable) NDEs precipitated by fear of death alone “fear-death experiences” (FDEs). Physiologically, such NDEs might be mediated by a fight-or-flight response in the absence of an actual medical crisis. In a case reported by Glen Gabbard and Stuart Twemlow, an NDEr dislodged the pin of a dummy grenade he thought to be a live one, producing a classic NDE similar to the one Pam experienced:

A marine sergeant was instructing a class of young recruits at boot camp. He stood in front of a classroom holding a hand grenade as he explained the mechanism of pulling the pin to detonate the weapon. After commenting on the considerable weight of the grenade, he thought it would be useful for each of the recruits to get a “hands-on” feeling for its actual mass. As the grenade was passed from private to private, one 18-year-old recruit nervously dropped the grenade as it was handed him. Much to his horror, he watched the pin become dislodged as the grenade hit the ground. He knew he only had seconds to act, but he stood frozen, paralyzed with fear. The next thing he knew, he found himself traveling up through the top of his head toward the ceiling as the ground beneath him grew farther and farther away. He effortlessly passed through the ceiling and found himself entering a tunnel with the sound of wind whistling through it. As he approached the end of this lengthy tunnel, he encountered a light that shone with a special brilliance, the likes of which he had never seen before. A figure beckoned to him from the light, and he felt a profound sense of love emanating from the figure. His life flashed before his eyes in what seemed like a split-second. In midst of this transcendent experience, he suddenly realized that grenade had not exploded. He felt immediately “sucked” back into his body (Gabbard and Twemlow 42).

Gabbard and Twemlow conclude that “thinking one is about to die is sufficient to trigger the classical NDE” (42). After comparing experiences that occurred in nonthreatening conditions with those where subjects were actually close to death, they also concluded that no particular elements were “exclusive to near-death situations,” but “several features of the experiences were significantly more likely to occur when the individual felt that death was close at hand” [emphasis mine] (42). That expectation alone can trigger NDEs in certain individuals, then, is well-documented.

If Pam had truly been out of body and perceiving, both her auditory and visual sensations should’ve been accurate; but when it came to details that could not have been guessed or plausibly learned after the fact, only her auditory information was accurate. Moreover, it is significant that as her narrative continues beyond the three visual observations outlined above, the remainder of her reported out-of-body perceptions are exclusively auditory. Finally, it is interesting that Pam reports uncertainly about the identity of the voice she heard when her OBE began: “I believe it was a female voice and that it was Dr. Murray, but I’m not sure” (Sabom, “Light” 42).

These facts strongly imply anesthesia awareness, and tend to count against the idea that Pam’s soul left her body during the operation. If her soul had left her body, the fact that her account contains out-of-body discrepancies doesn’t make much sense. But it makes perfect sense if she experienced anesthesia awareness, particularly when one looks at which sorts of information that she provided were accurate and which were not. Pam Reynolds did not report anything that she could not have learned about through normal perception, and this is exactly what we would expect if normal perception alone was operating during her OBE. It is little wonder that Fox concludes that “the jury is still very much out over this case” (Fox 210).

NDEs in the Blind?

As Susan Blackmore reported in Dying to Live, as of 1993, even Kenneth Ring conceded (in his own words) that there hadn’t been a single “case of a blind NDEr reported in the literature where there was clear-cut or documented evidence of accurate visual perception during an alleged OBE” (Blackmore, “Dying” 133). But Blackmore’s unsuccessful search for such cases prompted Ring and a doctoral student, Sharon Cooper, to endeavor upon a search of their own.

The results of their search are published most prominently in their joint 1999 book Mindsight: Near-Death and Out-of-Body Experiences in the Blind. There they document 31 cases of blind persons who had NDEs or OBEs, 10 of which were not medically close to death at the time of their experiences. These cases were garnered from responses to an advertisement in the International Association for Near-Death Studies (IANDS) Newsletter Vital Signs, as well as from contacts in 11 different organizations for the blind. Of the 31 persons in the sample, 14 were born blind, 11 lost their sight after they were five years old, and 6 were highly visually impaired. 25 of the 31 reported visual sensations during their experiences, as did 9 of the 14 persons blind from birth. The most startling claim made in Mindsight is not simply that some blind NDErs testify to gaining knowledge of facts they could only have learned through a faculty like vision, but that relevant eyewitnesses can corroborate their testimony.

But is there actually strong evidence of veridical paranormal perception in Ring and Cooper’s sample of blind NDErs? One reason Fox questions the significance of this study is that those known to acquire sight for the first time, or reacquire it after a very long time, have difficulty making sense of their visual sensations. He notes the case of a 52-year-man who, after receiving corneal grafts, could not visually identify a lathe that he was otherwise well-acquainted with—by touch—unless he was given the opportunity to touch it. Continually frustrated at his inability to interpret his visual sensations, he eventually took his own life a full two years after the operation (Fox 225-226). By contrast, Ring and Cooper’s blind NDErs are said to have “virtually immediately [gained] the ability to perceive accurately just such things as hospitals and streetlights with virtually no difficulty whatsoever” (226). While Ring and Cooper interpret this as evidence of a previously unknown sort of synesthetic perception ‘transcending’ normal human vision (224), Fox points out that more mundane sources—such as learning from mass media or NDE researchers that OBEs, tunnels, and lights are to be expected during near-death crises—might more satisfactorily explain the blind NDErs’ testimonies (239). Irwin notes similar possibilities:

[These cases] may be inspired by accounts of other people’s NDEs that have been widely disseminated in various forms of the media. That is, might a blind person have heard that people see certain things in a near-death encounter and unconsciously generated a fantasy that conformed to this belief?… [Blind NDErs might also] learn about what to expect in an afterlife from diverse sociocultural sources, and they may rely extensively on these expectations in generating a near-death fantasy…. Thus, the blind may commonly have a belief that they will suffer no visual affliction in an afterlife, and this belief may influence the content of NDEs in the blind (Irwin, “Mindsight” 112).

Fox adds that Ring and Cooper’s two most impressive cases are suspect as evidence for paranormal perception in the blind. In one of these cases, for instance, though an NDEr was said to have superior perceptual capabilities—like “omnidirectional awareness” of the environment—her out-of-body ‘perceptions’ were colorblind. But surely, Fox interjects, “we should expect in such a situation to see in colour. Indeed, we might reasonably expect to appreciate more, deeper and greater colour in such a condition, not less colour or none at all” (Fox 232). In the other case, a 33-year-old man reported an NDE when he was 8-years-old. But, Fox adds, one “might seriously question whether the testimony, twenty-five years after the event, of an episode that occurred to an 8-year-old boy, should qualify as one of their two most impressive cases” (231). Most significantly, though, Fox notes the statistical improbability of NDE researchers finding any genuine cases of NDEs in the blind:

Further, the reader may wonder at the statistical improbability of some of the events that Ring and Cooper present. NDEs seem quite rare, despite the recent publicity that has surrounded them. In this context, for example, it is worth noting that a recent study organized by British theologian Paul Badham and neuroscientist Peter Fenwick, which attempted to gain empirical support for the hypothesis that something leaves the body during an NDE, foundered because of a paucity of cases in the hospital chosen for the study. To find NDEs in the blind, therefore, would seem to be an incredibly difficult task. That Ring and Cooper found twenty-one such cases [31 if you include OBEs not near death] is an extraordinary achievement. That one of their two best cases [the colorblind one] was referred by the same social worker [Kimberly Clark] as was involved in the celebrated ‘tennis shoe’ case, and indeed came from the same hospital, seems most striking—and incredibly statistically improbable (Fox 232).

But Fox’s analysis does not end here. What of the alleged cases of veridical paranormal perceptions in these blind NDErs? While Ring and Cooper recognize the need for corroboration from others of the events NDErs report, and indeed present cases claiming exactly that, Fox notes that “a critical reading of the quality of the data presented reveals the need for caution in accepting them unreservedly” (232). He points out, for instance, that in one case passed on to Ring and Cooper by another NDE researcher, no one appears to have ever followed-up with potential witnesses (232). In another seemingly impressive case, a man who had been blind for 10 years reported an OBE after laying down on a couch where he could see a tie that he was wearing purchased for him by a friend who had never described it to him. The NDEr reported how amazed his friend was when he accurately described the patterns on the tie to her (233). But upon interviewing the friend, Ring and Cooper found that she could not really corroborate his recollection:

Although Ring and Cooper present this as a ‘corroborative’ case of sight during a blind respondent’s out-of-body experience, it is clear that it is not. The witness does not remember clearly the events or the tie. She thus cannot corroborate the detail of the episode in question, but merely presents a testimony to Frank’s apparent truthfulness and simply thinks that he was ‘probably accurate’ in the details given…. Once again, therefore, we must exercise care with the quality of the data presented…. More cautious commentators may be forgiven for suggesting that much stronger data are needed before they agree that existing scientific paradigms need to be hauled down and news ones erected (Fox 234).

Thus Blackmore’s conclusion about paranormal perception during NDEs (including NDEs in the blind) prior to Ring and Cooper’s study is just as poignant today as it was over a decade ago:

I think it would not be surprising if there were many claims of paranormal perception in NDEs even if it never happened. It is my impression that it probably never does happen…. [F]or the moment at least, these claims present no real challenge to a scientific account of the NDE (Blackmore, “Dying” 134-135).

NDE Target Identification Experiments