Empty Defense of an Empty Tomb: A Reply to Anne A. Kim’s Misunderstandings (2012)

Jeffery Jay Lowder

1. Kim’s Misunderstanding of My Thesis

1.1 The Application of Bayes’ Theorem to Empirical Hypotheses

1.2 The Relocation Hypothesis

2. Kim’s Defense of Craig’s Empty Tomb Evidence

2.1.1 First Stage: Is the Burial Story Historically Reliable?

2.1.1.1 The Nonburial Hypothesis

2.1.1.2 Dishonorable Burial Hypothesis

2.1.1.3 Honorable Burial Hypothesis

2.1.2 Second Stage: Is the Burial Story Evidence for an Empty Tomb?

2.2 Paul’s Knowledge

2.3 Pre-Markan Passion Story

2.4 Primitiveness of Markan Expression, “First Day of the Week”

2.5 The Story is Simple and Lacks Legendary Development

2.6 The Gospels’ Report that the Tomb was Discovered by Women

2.7 The Investigation of the Empty Tomb by Peter and John

2.8 Could First-Century Non-Christians Preach the Resurrection in Jerusalem if Jesus Lay in the Grave?

2.9 Does Jewish Propaganda Provide Independent Confirmation of the Empty Tomb Story?

2.10 Jesus’ Tomb was Not Venerated as a Shrine

William Lane Craig argues for the historicity of Jesus’ empty tomb on the basis of ten lines of evidence.[1] In a 2001 article I concluded that Craig had not yet shown that any of his ten items of evidence make the empty tomb more probable than not.[2] A significantly revised version of that article was published as a chapter in my 2005 book coedited with Robert M. Price, The Empty Tomb: Jesus Beyond the Grave.[3]

In a contemptuous and poorly argued essay[4], Anne A. Kim attempts to defend some of Craig’s arguments against my objections. While I welcome critical discussions of my work, Kim’s personal attacks are unfortunate and particularly unjustified because they are predicated upon repeated misunderstandings of my arguments. All that Kim has demonstrated is that it is much easier to attack caricatures of my arguments than the actual arguments themselves. In any case, if Kim’s replies are the best that empty tomb apologetics has to offer, then critics of those apologetics have an easy job.

Although her essay is introduced as a 2005 revision of a work originally published in 2001, it is not clear to me that Kim has even read my 2005 chapter. Thus I will ignore both Kim’s personal attacks and any objections not applicable to my 2005 chapter. I will now briefly state why I think Kim’s substantive defenses are utterly ineffective.

1. Kim’s Misunderstanding of My Thesis

1.1 The Application of Bayes’ Theorem to Empirical Hypotheses

Whenever arguing that such-and-such an event probably did or did not happen, a historian is appealing to probability. Craig’s arguments for the historicity of the empty tomb are no exception. Indeed, in his writings on the Resurrection, he clearly states as much:

The goal of historical knowledge is to obtain probability, not mathematical certainty. An item can be said to be a piece of historical knowledge when it is related to the evidence in such a way that any reasonable man ought to accept it. This is the situation with most all of our knowledge: we accept what has sufficient evidence to render it probable. The knowledge that the earth is round, that there are mountains out there, even that there are other people in the same room, is based on probability. Similarly, in a court of law, the verdict is awarded to the case that is made most probable by the evidence. The jury is asked to decide if the accused is guilty—not beyond all doubt, which is impossible—but beyond all reasonable doubt. It is exactly the same in history: we should accept the hypothesis that provides the most plausible explanation of the evidence.[5]

Given that historical arguments are shot through with appeals to probability, it is useful to introduce Bayes’ theorem as a way of clarifying the role of probability in historical argumentation. Let E be the evidence to be explained, H be our explanatory hypothesis for E, and B represent our relevant background knowledge. B includes all of our information relevant to H other than evidence E. B includes facts that determine the intrinsic probability of rival explanatory theories and facts that partially determine their explanatory power. E includes unusual facts within the context of this background that need to be explained.[6]

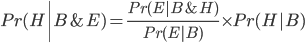

We are now in a position to introduce Bayes’ theorem, a mathematical formula for representing the effect of new information upon our degree of belief in a hypothesis. In one form, Bayes’ theorem may be expressed as follows:

where

Pr(E / B) = Pr(E / H & B) X Pr(H / B) + Pr(E / ~H & B) X Pr(~H / B).

Pr(H | B) is the prior probability of H with respect to B—a measure of how likely H is to occur at all, whether or not E is true. Pr(E | H & B) is the predictive power of H—the probability of E, given the truth of both B and H. Pr(E | B) is the prior probability of E with respect to B—how likely E is to be true a priori, whether or not H holds. The explanatory power of H is the ratio of Pr(E | H & B) to Pr(E | B). In other words, explanatory power refers to the ability of a hypothesis to explain (i.e., make probable) an item of evidence. Finally, Pr(H | E & B) is the final probability with respect to the total evidence B and E.

Although it is rarely possible to assign precise numerical values to each of these components when assessing alleged historical events, Bayes’ theorem is nevertheless extremely useful because it provides the logical foundation for several of our intuitive beliefs about inductive arguments. Consider, for example, the common-sense principle, “The more implausible the hypothesis, the greater the evidence needed to confirm it.” Bayes’ theorem captures this principle mathematically by saying that the final probability of H, given E and B, is equal to the product of H’s explanatory power and its prior probability.

1.2 The Relocation Hypothesis

In my 2005 chapter I granted that Jesus’ tomb was indeed found empty by his female followers on Easter morning. Nevertheless, I concluded that none of Craig’s ten arguments for the historicity of the empty tomb, considered individually, were inductively correct. Moreover, there are good reasons for believing that the relocation hypothesis, not the resurrection hypothesis, is a better explanation for the empty tomb.

Allow me to explain. The relocation hypothesis is the view that Jesus’ body was stored (but not buried) in Joseph’s tomb Friday before sunset, and moved on Saturday night to a second tomb in the graveyard of the condemned, where Jesus was buried dishonorably. From a logical perspective, what is significant about this hypothesis is that it entails an empty tomb. In other words, if the relocation hypothesis is true, there is a 100% probability that Jesus’ female followers discovered his (first) tomb empty on Sunday morning.

In contrast, the resurrection hypothesis does not presuppose an empty tomb. By itself, the resurrection hypothesis tells us nothing about whether there was an empty tomb, since the resurrection hypothesis is compatible with a wide variety of auxiliary hypotheses concerning the status of Jesus’ corpse between the time of his death and the time of his alleged resurrection. For all we know antecedently—that is, prior to considering the specific evidence—Jesus could have been denied burial and could have risen from the cross, not the grave. Or perhaps individuals who were resurrected in a tomb might decide to stay in the tomb eternally marveling at their own resurrection body. In order to guarantee an empty tomb, the resurrection hypothesis must be combined with at least one other hypothesis, such as the honorable burial hypothesis. In other words, given only the truth of the resurrection hypothesis, the probability of an empty tomb is less than 100%. By definition, then, the relocation hypothesis has more power to explain the empty tomb than the resurrection hypothesis.

I also provided an argument to show that the relocation hypothesis has a nonnegligible prior probability. Again, by ‘prior probability’ I mean the probability that the relocation hypothesis is true at all, independent of its explanatory power. Joseph of Arimathea was not a secret disciple of Jesus, but a pious Jew acting in accordance with Jewish law. Therefore, it is antecedently much more probable that Joseph used his own tomb to temporarily store Jesus’ body than that Joseph used his own tomb to bury Jesus. But if Joseph’s only motivation for burying Jesus were compliance with Jewish law, surely Joseph would have also complied with the Jewish regulation that condemned criminals must be buried in the graveyard of the condemned. Thus, the same historical precedent that gives the nonburial hypothesis a low prior probability also gives the relocation hypothesis a high prior probability.

Of course, a hypothesis could have both a high prior probability and great explanatory power regarding an individual item of evidence, but still have a final probability that is less than 50%. For example, the hypothesis could be highly improbable given other items of evidence.

In my chapter I concluded that the relocation hypothesis has both a high prior probability and great power to explain the empty tomb, but I did not conclude that the relocation hypothesis is true. Instead, I urged agnosticism about the truth of the relocation hypothesis. Why? For two reasons. First, as I stated in the article, we lack direct evidence in support of the relocation hypothesis. Second, in order to have an inductively correct argument for the truth of a hypothesis, one must consider all of the relevant evidence. The scope of my already lengthy chapter, however, was limited solely to Craig’s evidence for the empty tomb.

Kim misinterprets my argument, however, and instead questions my sincerity. That she has failed to understand the thesis of my chapter is apparent from the very beginning of her article. She writes:

Jeffery Jay Lowder: “Polemical rumors need neither a basis in historical fact nor even sincere belief among those who spread them.”

That seems a fitting summary of the recently-released article by Lowder…

Since I suspend judgment on the truth of the relocation hypothesis, does it follow that my defense of the explanatory superiority of that hypothesis is accurately summarized as a “polemical rumor?” No, it does not. In the first place, unlike the Jewish hearsay evidence in Matthew 28, my paper is not a “rumor.” While we do know the identity of the author of my chapter, we don’t know the name(s) of the individual(s) who originally accused the disciples of theft. More importantly, the relocation hypothesis has a basis in historical fact insofar as the available evidence regarding Jewish burial customs for executed criminals raises the hypothesis’ prior probability. By contrast, neither Craig nor Kim have yet offered any reason to believe that the resurrection hypothesis has a nonnegligible prior probability, much less a prior probability that is equal to or greater than that enjoyed by the relocation hypothesis. Finally, despite Kim’s uncertainty, I do sincerely believe that the relocation hypothesis has greater power to explain the empty tomb than the resurrection hypothesis.

Kim continues:

…which advances some theories about the empty tomb that have no direct evidence and which, after reading, I am unsure whether he sincerely believes.

This is just confused. The conclusion of my chapter makes it obvious that I believe both that (i) the relocation hypothesis is a better explanation of the empty tomb than the resurrection hypothesis (i.e., has greater explanatory power) and (ii) we should nevertheless suspend judgment regarding the truth (or final probability) of the relocation hypothesis. I clearly wrote, “We lack direct evidence for the relocation hypothesis. According to McCullagh’s methodology, then, we should suspend judgment on it.”[7] In light of that statement, it is puzzling that Kim would be “unsure” about my views.

Unfortunately, as we shall see, this is by no means the only significant point in my chapter that Kim misunderstands. Let us now turn to Kim’s defense of (some of) Craig’s evidence for the empty tomb.

2. Kim’s Defense of Craig’s Empty Tomb Evidence

In his written work on the Resurrection, Craig has appealed to ten items of evidence in support of the empty tomb. Kim defends seven of these items against my objections. Let’s consider each in turn.

2.1 The Burial Account

Craig’s argument from the reliability of the burial story to the empty tomb has two stages. The first stage appeals to different features of the Markan burial story in an attempt to show that Joseph of Arimathea honorably buried Jesus in a tomb. The second stage of his argument is intended to show that the reliability of the burial story is evidence for the empty tomb.

2.1.1 First Stage: Is the Burial Story Historically Reliable?

Was Jesus buried and, if so, how? There are three possibilities: the nonburial hypothesis, the dishonorable burial hypothesis, and the honorable burial hypothesis. In my chapter, I discussed all three alternatives and concluded that a version of the dishonorable burial hypothesis is the best explanation. Let us consider Kim’s replies to my arguments.

2.1.1.1 The Nonburial Hypothesis

Given that both Kim and I reject the nonburial hypothesis, one might expect there is little to discuss here. Kim does, however, object to one of my points.

(a) The prior probability that a victim of Roman crucifixion would be buried is low.

Another of Kim’s misunderstandings is evident in the very first sentence of her substantive reply to my chapter. She writes, “Lowder tries to make a case that Jesus’ burial was itself improbable because it is not the typical Roman practice to bury crucifixion victims.” This is not an accurate summary of the argument, however. What I actually argued is, “there is a low prior probability that the crucifixion victim would be buried.”[8] There is a huge difference between “Jesus’ burial was itself improbable” and “there is a low prior probability that the crucifixion victim would be buried.” The latter is a statement about prior probability—the measure of how likely burial of a crucifixion victim is to occur at all, whether or not some specific item of evidence is true. In contrast, the former is a statement about the final probability of Jesus’ burial. The final probability of an event is a function of both its prior probability and its explanatory power. As Kim writes, in some cases, “The exception is not so unusual or unthinkable as to cause doubt, and the evidence that it happened overcomes the fact that it’s not typical.” This is correct, but it is unclear why Kim feels that this is somehow relevant to her critique. As I wrote in my chapter, on the basis of points (b)-(e) below, “I believe that the specific evidence for Jesus’ burial is sufficient to overcome the intrinsic improbability of a crucifixion victim being buried.”[9] Hence, Jesus’ burial has a high final probability. In other words, the specific evidence relevant to Jesus’ burial “overcomes the fact that” burial of Roman crucifixion victims is “not typical.” That Kim attempts to use a conclusion about final probability against a premise about prior probability demonstrates how badly she has misunderstood the logical structure of my argument and, apparently, Bayes’ theorem.[10]

(b) There is historical precedent both for the Romans to allow a crucifixion victim to be buried and for the Jews to bury the corpses of their enemies.

No response from Kim.

(c) For victims of ‘mass’ crucifixions, the prior probability of burial is extremely low.

No response from Kim.

(d) The prior probability of burial for victims of ‘small’ crucifixions is low, but not extremely low.

No response from Kim.

(e) The prior probability that a pious Jew would approach Pilate and ask for Jesus’ body is high.

No response from Kim.

2.1.1.2 Dishonorable Burial Hypothesis

I also argued that Jesus’ dishonorable burial has a high prior probability. Moreover, the relocation hypothesis is superior to the generic dishonorable burial hypothesis for the following reasons.

(a) The Markan story portrays the burial as rushed.

No response from Kim.

(b) If John 20:2 has a historical basis, Mary apparently thought Jesus had been moved.

No response from Kim.

(c) Joseph would have defiled his own tomb by storing Jesus’ body in it.

No response from Kim.

(d) The relocation hypothesis explains the empty tomb itself.

No response from Kim.

(e) The disposition of the two thieves poses no problem for the relocation hypothesis.

Kim presents two objections: (i) “For while there is positive evidence that Joseph of Arimathea buried Jesus, there is no evidence that he buried anyone else”; (ii) the relocation hypothesis “requires us to believe that the body simply being moved didn’t occur to the women at the tomb. On the contrary, we find from John’s account that that was the first thought that Mary Magdalen had.”

I find objection (i) puzzling. Perhaps Kim is presenting the following argument from silence:

There is no textual evidence that Joseph buried anyone else.

Therefore, Joseph did not bury anyone else.

Some arguments from silence are inductively correct—that is, their premises confer a high degree of probability upon the conclusion. The argument presented above, however, is not inductively correct. The argument’s sole premise does not make the conclusion highly probable. In order to make it inductively correct, Kim would have to add at least one premise, presumably of the sort, “If Joseph had buried anyone else, we would expect to find textual evidence of that today.” Such a premise is not presented in her paper, and more importantly, the truth of such a premise would be doubtful. Even if Joseph had buried the two thieves, it is far from obvious that the Gospel writers (or anyone else) would have mentioned it.

Besides, even if Joseph did not bury the two thieves, Kim has not shown that that would pose an evidential problem for the relocation hypothesis. I think that the burial of the two thieves by Joseph has a high prior probability. Again, if Joseph’s only motivation for burying Jesus were compliance with Jewish law, surely Joseph would have also complied with the Jewish regulation that condemned criminals must be buried in the graveyard of the condemned.

Objection (ii) is simply false. The relocation hypothesis is compatible with the women suspecting relocation. Indeed, if the women did suspect relocation (as John 20:2 states), then their suspicions would constitute some evidence for the relocation hypothesis.

2.1.1.3 Honorable Burial Hypothesis

Next, I critiqued various arguments offered in support of the honorable burial hypothesis.

(a) Craig has not shown that Paul’s testimony provides evidence of burial by Joseph of Arimathea.

Kim writes: “Paul independently documents the fact that Jesus was buried.” I agree, but this response misses the point. 1 Corinthians 15:3 says that Jesus was buried; it does not say that Jesus was buried honorably by Joseph of Arimathea.

(b) As a member of the Sanhedrin, it is unlikely that Joseph of Arimathea is a Christian invention.

No response from Kim.

(c) Joseph’s laying the body in his own tomb may be historical.

Kim agrees with (c), but takes issue with my further point that it is doubtful that Joseph would have intended to leave Jesus’ body in his tomb any longer than absolutely necessary. She argues that (i) the relocation hypothesis requires that all of the appearance stories are fabrications, and (ii) either Joseph was never asked about the body, or if he was, that he didn’t make his activities known. In her words, the relocation hypothesis entails that “Joseph of Arimathea had the knowledge, the power, and the motivation to stop Christianity in its tracks—but didn’t.” Both of these objections are doubtful, however.

Objection (i) is nothing but an assertion without any supporting evidence or argument. The relocation hypothesis is compatible with the Gospel authors’ sincere belief that they had seen someone alive who looked like Jesus after his death. This gets us into some very murky waters, however, and is well beyond the scope of my original reply to Craig, which was focused solely on the evidence of the empty tomb. In effect, this objection does not deny that the relocation hypothesis is a better explanation for the empty tomb than the resurrection hypothesis; instead, it makes the argument that the relocation hypothesis is a poor explanation for other items of evidence (namely, the appearance stories). And although Kim has not presented an inductively correct argument for the conclusion that the evidence of the appearance stories undermines the relocation hypothesis, there may indeed be such an argument. This is one reason why I have always been careful to argue that the relocation hypothesis has great power to explain the empty tomb, but I have never argued that the relocation hypothesis is probably true.

Objection (ii) simply does not follow. The two alternatives listed—that either Joseph was never asked, or that he was asked and did not make his activities known—are not exhaustive. It is also possible that Joseph died or left Jerusalem. If Jesus died or left Jerusalem, we would not expect Joseph to have answered questions about his activities. Given the silence of the Gospels on Joseph’s whereabouts following the burial, it seems to me that there is insufficient evidence to draw any conclusions about whether Joseph did indeed have the power to inform the disciples of the relocation. At least, Kim has presented no evidence that Joseph had the power to inform the disciples of the relocation.

(d) That Jesus was buried late on the Day of Preparation is question-begging.

No response from Kim.

(e) The alleged lack of competing burial traditions is irrelevant.

No response from Kim.

In sum, Kim has not vindicated Craig’s arguments in defense of an honorable burial. The evidential implications of Jesus’ burial are addressed in the second stage of Craig’s argument, to which we now turn.

2.1.2 Second Stage: Is the Burial Story Evidence for an Empty Tomb?

In my reply to Craig, I argued that even if the disciples knew the location of Jesus’ tomb, that fact would still not bolster the credibility of the empty tomb story. I gave three reasons.

(a) One could believe that Jesus was honorably buried and yet justifiably reject the claim that no other corpses were buried in Jesus’ tomb.

No response from Kim.

(b) Even if Jesus had been buried alone in a known location, that fact would still not increase the likelihood that Jesus’ (second) tomb was empty.

No response from Kim.

(c) Even if the Jewish authorities did try to refute the resurrection by pointing to the second tomb, there is no reason to believe [that] they would have done so until seven weeks after the first tomb had been discovered empty.

No response from Kim.

Thus, neither Craig nor Kim have yet provided an inductively correct argument for believing that the burial story is evidence of an empty tomb.

2.2 Paul’s Knowledge

Following Craig, I distinguish between Paul’s belief that the tomb was empty versus Paul’s knowledge of an empty tomb. On the latter, I wrote:

At first glance, it seems terribly uncertain whether Paul knew of an empty tomb [emphasis added].

Commenting on this sentence, Kim claims that I have ignored the “meaning of resurrection,” again badly misunderstanding my point. First, her objection ignores the distinction (introduced by Craig himself[11]) between Paul’s belief that the tomb was empty versus Paul’s knowledge of an empty tomb. So even if the “meaning of resurrection” entailed an empty tomb, it still wouldn’t follow that Paul had knowledge of an empty tomb. All that would follow from the “meaning of resurrection” would be that Paul believed in an empty tomb, which I never questioned in my chapter. Second, as we saw in section 1, the concept of resurrection, by itself, does not mean that there was an empty tomb. So the “meaning of resurrection” poses no problem for my argument.

Returning to my chapter, next I sketched in passing Uta Ranke-Heinemann’s argument from silence, which Kim misinterprets as a defense of that argument.[12] Allow me to set the record straight: I am just as skeptical of Ranke-Heinemann’s argument as I am of Craig’s argument. Craig argues that Paul knew of an empty tomb from two sources: Paul’s conversations with various Christians who knew that it was empty, and his own alleged visit to Jesus’ burial place, prior to his conversion.[13] Let us now turn to my critique of this argument, along with Kim’s defense.

(a) Craig has not shown that Paul knew of an empty tomb from the disciples.

In my chapter I agreed with Craig that it is highly probable that Paul would have talked with other Christians about the Resurrection. In order to conclude that Paul knew of an empty tomb, however, we need an additional argument showing that the disciples in turn knew of an empty tomb. Kim does not provide such an argument in her response.

(b) Craig has not shown that Paul probably visited the empty tomb before his conversion.

In my critique of Craig, I observed three things: (i) Craig had not yet provided an argument to show that Paul probably visited the empty tomb before his conversion; (ii) it is far from obvious that Jewish opponents of the Christian Way in the early 30s, before Paul’s conversion, took seriously the claim that there was an empty tomb; and (iii) even if Paul did visit the tomb, we don’t know when the visit took place. In her reply, Kim ignores points (ii) and (iii) and only mentions (i).

In defense of (i), I wrote:

…note the nature of Craig’s claim: he simply suggests that Paul may have visited the empty tomb before his conversion, not that Paul probably did. Yet even if some Jews had checked Jesus’ burial place, that doesn’t make it probable that Paul would have visited that location himself. The pre-Christian Paul would not have had to personally go to Jesus’ burial place in order to believe his fellow Pharisees who stated that, say, Jesus’ corpse was rotting.[14]

In response, Kim writes: “If any such thing had actually happened, it is overwhelmingly unlikely that Paul would have ever become a Christian.” Yet this reply misses the point, namely, that the pre-Christian Paul would not have had to personally go to Jesus’ tomb in order to believe whatever his fellow Pharisees were saying. This would be the case even on the assumption that the tomb was, in fact, empty, and the Pharisees told Paul as much. Hence, neither Craig nor Kim have yet shown that the pre-Christian Paul probably visited Jesus’ tomb.

2.3 Pre-Markan Passion Story

Craig asserts that the pre-Markan passion story provides evidence of the empty tomb. I offered two objections.

(a) The arguments for and against the passion story including the empty tomb story are inconclusive. And even if the pre-Markan passion story did include the empty tomb story, the identity or reliability of the women is unknown, so the value of their testimony is likewise uncertain.

As I wrote in my reply to Craig, the grammatical and linguistic features of the passion narrative could just be the product of the late author’s editing. Neither Craig nor Kim provide any evidence to the contrary.

Kim also argues that the identity of the witnesses was known since “a number of other accounts do mention the women by name.” This reply just misses the context of my reply to Craig’s third argument. What is under consideration is an argument against the hypothesis that the empty tomb is a legend, based upon the alleged fact that there was a pre-Markan passion story that is very old and included the empty tomb story. Unless there is some reason to believe that the pre-Markan passion story attributed the same names to the women as the other accounts, however, the inclusion of names in other accounts is irrelevant to the evidential value of the pre-Markan passion story. We would still be left with hearsay testimony in which the reliability of the primary source(s) is unknown.

(b) The “high priest” need not have been Caiaphas.

No response from Kim.

2.4 Primitiveness of Markan Expression, “First Day of the Week”

Kim writes: “Lowder documents that the argument advanced by Craig is not widely viewed as conclusive within Christianity itself.” It is unclear whether she agrees that this is not evidence for an empty tomb, or merely that the argument is not widely accepted among Christians. In any case, Kim provides no response to my critique of Craig’s argument.

2.5 The Story is Simple and Lacks Legendary Development

(a) The relative simplicity of the Markan story does not make it likely that the story is true.

No response from Kim. It is significant that Kim is silent on this point, since it is the most important of my three replies to Craig’s fifth argument for the empty tomb. Even if my points (b) and (c) below were incorrect, the fact remains that the relative simplicity of the Markan story does not, by itself, make it likely that the empty tomb story is true.

(b) The reference to the “young man” is legendary, as argued by E. L. Bode.

In response to this point, Kim simplistically writes: “This seems to beg the question of whether angels are legendary beings,” as if the only way to deny the historicity of an individual story about an angel is to assume that all stories involving angels are legendary. The absurdity of such an approach to the historicity of angelic stories is belied by E. L. Bode, a Roman Catholic scholar who (i) has no axe to grind against the supernatural, (ii) Craig relies heavily on in his writings, and (iii) I quoted in my chapter. According to Bode, the angelic appearance in the Markan empty tomb story is legendary for two reasons. It is worth quoting him again in full:

Rather our position is that the angel appearance does not belong to the historical nucleus of the tomb tradition. This omission does not call into question the existence of angelic beings. This stance is taken for two reasons: (1) the kerygmatic and redactional nature of the angel’s message and (2) the omission gives a better insight into the tomb tradition and its development.[15]

What response does Kim give to Bode’s two points? None whatsoever. She is completely silent about both points. Instead, she adduces an independent argument in support of the historicity of the angel: the saying of the angel can be traced back “with probability” to a common source relied upon by the authors of both Matthew and Mark. Even if Kim is right about this, however, she hasn’t yet offered any argument showing that that would make it likely that the angelic appearance is historical, or that the Markan empty tomb story is true. In order to show that the angelic appearance has a high final probability, she would have to take into account all of the relevant evidence, including both of Bode’s points. She has yet to do so.

(c) If Craig is correct that the women’s silence was temporary, then that would be a legendary embellishment.

Kim objects that a temporary silence is not legendary, for there is nothing “remarkable about people being scared upon leaving a graveyard, especially if the body weren’t there.” Here we have another of Kim’s misunderstandings. I agree that it is unsurprising that people would be scared upon leaving a graveyard if the body they expected to find there was not present. But my reasoning for (c) never denied that point, so Kim is attacking a straw man. My actual point was: if we are careful to avoid reading the later Gospels into Mark, the most straightforward construal of Mark’s empty tomb story is that the silence was permanent. Craig himself admits that Mark 16:8 “represents the original conclusion to that gospel.”[16] Since Mark ended his gospel at verse 8 with the women running away and telling “no one” what they had seen—in direct contrast to Matthew and Luke, who allege that the women told others—this could easily be an attempt on Mark’s part to present a plausible reason why “no one” had heard his tale of the empty tomb until some time had passed. The women were so afraid that they didn’t tell anyone what they had seen; hence, that would be why the early tradition didn’t develop.

2.6 The Gospels’ Report that the Tomb was Discovered by Women

Kim draws a distinction between “conclusive” and “useful” arguments. She argues, accordingly, that Craig’s sixth argument is “useful” since it “lend[s] weight to the factuality of the account.” I’m happy to join her in making the distinction, but I prefer to use the standard jargon of logic, and hence will distinguish between deductive and inductive arguments. Instead of asking, “Is Craig’s sixth argument useful?” I propose that we instead ask, “Is Craig’s sixth argument inductively correct?”

In my chapter I argued that Craig’s sixth argument is overstated: the role of the women in the story is not as improbable given the legend hypothesis as Craig suggests. I offered three supporting reasons: (i) the women were not portrayed as legal witnesses in the story; (ii) women were qualified to serve as legal witnesses if no male witnesses were available; and (iii) on the assumption that the legend hypothesis is true, any embarrassment associated with the role of women in the story would have been outweighed by the embarrassment associated with the lack of a detailed story of the empty tomb prior to Mark. Kim provides no response to these points in her reply.

2.7 The Investigation of the Empty Tomb by Peter and John

(a) I shall assume the authenticity of Luke 24:12.

In summarizing my discussion of (a), Kim makes the curious statement that I “argue” that Luke 24:12 is an interpolation. I make no such argument. What I did was sketch, not defend, an argument against the historicity of the visit by Peter and John. I then pointed out that that argument requires that Luke 24:12 be an interpolation, an assumption that I was not willing to defend. That Kim has badly misunderstood my discussion is evident from my statement, “I shall assume that the verse is authentic.”[17]

(b) If the women were not legally qualified to serve as witnesses, then this would render the disciples’ visit to the tomb unlikely.

No response from Kim.

(c) … I am willing to concede the historicity of the visit …

Although I clearly state that I grant the historicity of the visit, Kim claims that I “argue from silence” that the “men checking the women’s story may not have happened.” Since this summary is inaccurate, I simply invite readers to compare Kim’s summary of my point to what I actually wrote.[18]

(d) Even if the women eventually broke their silence, surely the author of Mark meant to convey that the women were silent for a longer period of time than it took them to return from the tomb to the disciples. But that would undermine the credibility of the story of the disciples’ visit to the tomb.

In response, Kim contends that (i) the women’s silence would not have served any suitable purpose in Mark’s account and (ii) like most silences, it is eventually broken. Both objections are spurious. Regarding (i), I have already provided in my chapter an explanation of how the silence could have served a suitable purpose in Mark’s empty tomb story: it could be Mark’s attempt to present a plausible reason why “no one” had heard his tale of the empty tomb until some time had passed. As for (ii), this point at best shows that there is some antecedent reason to expect the women’s silence to be temporary. It does not undermine point (d): surely the author of Mark meant to convey that the women were silent for a longer period of time than it took them to return from the tomb to the disciples.

(e) The relocation hypothesis is consistent with a visit to the first tomb by Peter and John, since the relocation hypothesis presupposes an empty (first) tomb.

No response from Kim.

2.8 Could First-Century Non-Christians Preach the Resurrection in Jerusalem if Jesus Lay in the Grave?

(a) Craig has not shown that first-century non-Christians were sufficiently interested in Christianity to want to refute it.

In her reply, Kim provides an independent argument for believing that first-century Jewish opponents of Christianity were sufficiently motivated to refute the Christian claim of a resurrection. Even if her argument were correct, this would not contradict (a), however, since the point of (a), like that of the paper as a whole, was to evaluate Craig’s defense of the empty tomb. Hence, my original objection stands. But in fact I think Kim’s argument fails. She argues that since the ruling council had condemned Jesus before his death, they would have been motivated to at least investigate rumors that he was alive. If the members of the ruling council had no knowledge of Jesus’ death, then this would be a good argument. But there is good reason to believe that at least some members of the ruling council did have knowledge of his death. Mark 15:31-32 states that “the chief priests and the teachers of the law” were present at the crucifixion and heaped insults on Jesus. It would not be surprising if those same individuals were present when Jesus died on the cross, and hence learned of Jesus’ death first-hand. If they had first-hand knowledge of his death, it is far from obvious that they would have been motivated to investigate rumors that he was alive.[19]

(b) Even if a non-Christian had been motivated to produce the body, for all we know, it could not have been identified by the time Christians began to publicly proclaim the resurrection.

Kim claims that (b) is a moot point given the relocation hypothesis, since

identification of the body would not have been necessary if Joseph of Arimathea had really reburied the body as Lowder claims. At any time, body or no, Joseph of Arimathea could have cleared up the whole thing by mentioning that he had reburied the body elsewhere.

In order to refute (b), however, Kim has to presuppose that Joseph was still in Jerusalem once the disciples began to proclaim the Resurrection. For all we know antecedently, however, Joseph may have left Jerusalem or died after he buried Jesus and before the disciples began to proclaim the Resurrection.[20] Again, Kim presents no evidence that Joseph was even in a position to comment on the location of Jesus’ corpse.

(c) It is doubtful that such disconfirming evidence would have “nipped the Christian heresy in the bud.”

No response from Kim.

2.9 Does Jewish Propaganda Provide Independent Confirmation of the Empty Tomb Story?

(a) Given that the polemic is not recorded in any contemporary Jewish documents, we can’t assume that Jews actually responded to the proclamation of the resurrection with the accusation that the disciples stole the body.

Once again Kim misunderstands my argument. She writes: “Lowder tries to argue from silence that, since we have no (other) Jewish documents confirming or denying this, that we can’t assume it’s true.” Kim seems to have missed the distinction between “We can’t assume S” and “S is false.” Let S be the accusation that the disciples stole the body. If I had argued, “Given the silence of contemporary Jewish sources about S, S is false,” then my argument could reasonably be characterized as an argument from silence. What I actually wrote, however, was: “Given that the polemic is not recorded in any contemporary Jewish documents, we can’t assume that Jews actually responded to the proclamation of the resurrection with the accusation that the disciples stole the body.” What is needed is an argument; I do not find such an argument in any of Craig’s writings on the Resurrection.

In her response, Kim tries to provide such an argument. She writes, “It is very likely that those who did not follow Christ would have tried to bring forward an alternate explanation of the empty tomb.” What that argument shows is that Jewish opponents of the Christian Way probably would have produced an alternate explanation of the empty tomb; in its current form, it does not show that they probably would have accused the disciples of theft.[21]

(b) There is no evidence that Jewish knowledge of the empty tomb presupposed by the polemic was based upon direct, first-hand evidence of an empty tomb.

No response from Kim.

(c) Jewish polemic was just that—polemic. Polemical rumors need neither a basis in historical fact nor even sincere belief among those who spread them. For all we know antecedently, the Jewish polemic is a hypothetical response to the empty tomb story.

Kim does not respond to (c), but instead states that my chapter is itself best characterized as polemic. As we have seen in section 1, however, this is incorrect.

2.10 Jesus’ Tomb was Not Venerated as a Shrine

I argued that the lack of veneration of Jesus’ tomb is antecedently no more likely on the assumption that Jesus’ tomb was empty than on the assumption that Jesus was buried dishonorably. In her rebuttal, Kim states that she has “seen other Christian apologists argue that Jesus’ tomb was venerated as a place of pilgrimage from the earliest years after Jesus’ resurrection.” Kim’s remarks are consistent with my chapter, where I noted that “I have yet to find a good argument for that conclusion [that Jesus’ burial place was not venerated as a shrine] in any of the secondary literature on the resurrection.”[22] If Jesus’ burial place was venerated as a shrine, then Craig’s tenth argument collapses.

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, then, I think that Craig’s arguments for the historicity of the empty tomb are not inductively correct as they stand. Nor do I think that Kim has succeeded in rehabilitating those arguments. Of course, this in no way rules out the idea that there may be other arguments for the historicity of the empty tomb that are successful. For example, it may be the case that Jewish burial customs presuppose that someone knew the location of the deceased, even the bodies of dead criminals buried in the graveyard of the condemned.[23] The position I have defended is that Craig’s arguments, as they stand, do not make the historicity of the empty tomb more probable than not.

Notes

[1] See, for example, William Lane Craig’s Assessing the New Testament Evidence for the Historicity of the Resurrection of Jesus, Studies in the Bible and Early Christianity 16 (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen, 1989), and his “Did Jesus Rise from the Dead?” in Jesus Under Fire: Modern Scholarship Reinvents the Historical Jesus ed. Michael J. Wilkins and J. P. Moreland (Grand Rapids, MI: 1995): 147-182.

[2] Jeffery Jay Lowder, “Historical Evidence and the Empty Tomb Story: A Reply to William Lane Craig.” Journal of Higher Criticism Vol. 8, No. 2 (Fall 2001): 251-293.

[3] Jeffery Jay Lowder, “Historical Evidence and the Empty Tomb Story: A Reply to William Lane Craig” in The Empty Tomb: Jesus Beyond the Grave ed. Robert M. Price and Jeffery Jay Lowder (Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books, 2005): 261-306.

[4] Anne A. Kim, “The Empty Tomb: A Reply to Jeffery Jay Lowder.” Accessed from http://members.aol.com/wordhome/depth/Risen02.htm on July 6, 2005; site discontinued.

[5] William Lane Craig, Apologetics: An Introduction (Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 1984), p. 147, quoted in Robert Greg Cavin, “Miracles, Probability, and the Resurrection of Jesus: A Philosophical, Mathematical, and Historical Study,” Ph.D. dissertation (University of California, Irvine, 1993), p. 203. Italics added.

[6] Robert Greg Cavin, “Miracles, Probability, and the Resurrection of Jesus: A Philosophical, Mathematical, and Historical Study,” p. 295.

[7] Jeffery Jay Lowder, “Historical Evidence and the Empty Tomb Story: A Reply to William Lane Craig” (2005), p. 297. Italics added.

[8] Jeffery Jay Lowder, “Historical Evidence and the Empty Tomb Story: A Reply to William Lane Craig” (2005), p. 264. Italics added.

[9] Jeffery Jay Lowder, “Historical Evidence and the Empty Tomb Story: A Reply to William Lane Craig” (2005), p. 265.

[10] Kim shows no familiarity with inductive logic, especially the concept of explanatory power and the distinction between prior probability and final probability. See: Brian Skyrms, Choice & Chance, 4th ed. (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 2000); Wesley Salmon, Logic, 3rd ed. (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1984); and Wesley Salmon, The Foundations of Scientific Inference (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh, 1966).

[11] William Lane Craig, Assessing the New Testament Evidence for the Historicity of the Resurrection of Jesus, p. 86.

[12] As a refutation of Ranke-Heinemann’s argument, Kim then writes: “This ignores the meaning of being raised from the dead.” The idea seems to be this: even if Paul did not explicitly mention an empty tomb, he did explicitly state that Jesus was risen from the dead, and rising from the dead entails an empty tomb. This, however, is incorrect. As I explained at the beginning of this paper, an empty tomb is not part of the meaning of resurrection. Given that a person was buried, their resurrection does not entail an empty tomb. An additional event, namely, the resurrected person’s leaving the tomb, must occur.

[13] William Lane Craig, Assessing the New Testament Evidence for the Historicity of the Resurrection of Jesus, pp. 112-14.

[14] Jeffery Jay Lowder, “Historical Evidence and the Empty Tomb Story: A Reply to William Lane Craig” (2005), p. 276.

[15] Edward Lynn Bode, The First Easter Morning AB 45 (Rome, Italy: Biblical Institute Press, 1970), p. 166.

[16] William Lane Craig, Assessing the New Testament Evidence for the Historicity of the Resurrection of Jesus, p. xvii.

[17] Jeffery Jay Lowder, “Historical Evidence and the Empty Tomb Story: A Reply to William Lane Craig” (2005), p. 286.

[18] Jeffery Jay Lowder, “Historical Evidence and the Empty Tomb Story: A Reply to William Lane Craig” (2005), p. 286.

[19] Furthermore, there may be a rebutting defeater lurking nearby. As Christian apologists frequently point out, first-century Judaism had no concept of a dying and rising messiah. That fact might be some evidence against the hypothesis that early Jewish opponents of Christianity would have been motivated to refute the Christian claim of a resurrection.

[20] I owe this point to Richard Carrier.

[21] My own views on this have evolved a bit since I wrote my 2005 chapter. I now believe that it can be shown that Jewish opponents of the Christian Way did accuse the disciples of stealing the body, but I am not persuaded by attempts to show that the accusation of theft can be dated before 70.

[22] Jeffery Jay Lowder, “Historical Evidence and the Empty Tomb Story: A Reply to William Lane Craig” (2005), p. 293.

[23] Dale C. Allison, Resurrecting Jesus: The Earliest Christian Tradition and Its Interpreters (New York, NY: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2005).

Copyright ©2012 Jeffrey Jay Lowder. The electronic version is copyright ©2012 by Internet Infidels, Inc. with the written permission of Jeffrey Jay Lowder. All rights reserved.